|

quote:I must digress briefly to remind you of the vast change that twenty-five years had wrought in my own fortunes. Back in ’49, though a popular hero in England, I’d been a nameless fugitive in the States; now, in 1875, I was Sir Harry Flashman, V.C., K.C.B., with all the supposed heroics of the Crimea, Mutiny, and China behind me, to say nothing of distinguished service to the Union in the Civil War. No one had been too clear what that service was, since it had seen me engaged on both sides, but I’d come out of it with their Medal of Honour and immense, if mysterious, credit, and the only man who knew the whole truth had got a bullet in the back at Ford’s Theatre, so he wasn’t telling. Neither was I – although I will some day, all about Jeb Stuart, and Libby Prison, and my mission for Lincoln (God rest him for a genial blackmailer), and my renewed bouts with the elfin Mrs Mandeville, among others. But that ain’t to the point just now; all that signifies is that I’d gained the acquaintance of such notables as Grant (now President) and Sherman and Sheridan – as well as such lesser lights as young Custer, whom I’d met briefly and informally, and Wild Bill Hickok, whom I’d known well (but the story of my deputy marshal’s badge must wait for another day, too). Ho mercy, that's a lot. Alright, in one sentance per:  Cameth the hour cameth the man.  "Other than that the play was fine, thank you for asking."  Great cavalry commander when he was around.  A bit too popular even for the government.  Cool head and a fast learner.  Just the man to point at your enemies.  Stood very tall (in the saddle). Alternately: How did it take this long to find an eastern man in blue who knew one end of the horse from the other?!  Sometimes blindly charging in shows shows the depth and sometimes it gets everyone killed.  ♫Pushing up the ante, I know you've got to see me, read'em and weep...♫ Anyway, back in a bit. Arbite fucked around with this message at 00:33 on Jun 12, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 5, 2024 20:09 |

|

Keep Mrs. Mandeville in mind as this is one of the few outright mistakes Fraser (or Flashy?) makes in the series.

|

|

|

|

Norwegian Rudo posted:Keep Mrs. Mandeville in mind as this is one of the few outright mistakes Fraser (or Flashy?) makes in the series.

|

|

|

|

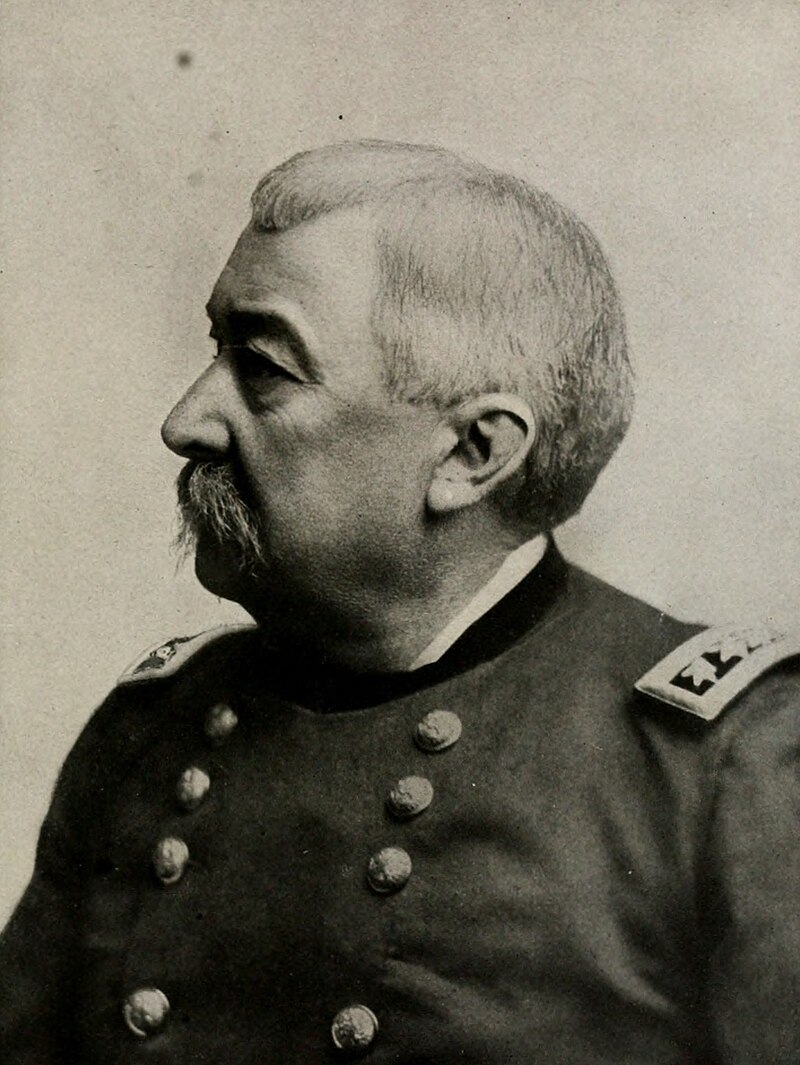

quote:So now you see Flashy in his splendid prime at fifty-three, distinguished foreign visitor, old comrade and respected military man, with just a touch of grey in the whiskers but no belly to speak of, straight as a lance and a picture of cavalier gallantry as I stoop to salute the blushing cheek of the new Mrs Sheridan at the wedding reception in her father’s garden.50 Little Phil, grinning all over and still looking as though he’d fallen in the river and let his uniform dry on him, led me off to talk to Sherman, whom I’d known for a competent savage, and the buffoon Pope, whose career had consisted of losing battles and claiming he’d won. They were with a big, abrupt cove, whiskered like a Junker, named Crook. That's Sherman alright. quote:Pope wagged his fat head and said he understood that some thousands had come into the agencies, and settled down quietly. Mind, at the end of the Civil War the Union had a million under arms. quote:“Gentlemen, we have a British spy in our midst!” says Sheridan, laughing. “Yes, that’s about right – but not all of those Indians are truly hostile, whatever Sherman thinks. Only a handful, in fact. The rest simply don’t want to live on agencies and reservations. The few real wild spirits – Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and the like – don’t amount to more than a few thousand braves. There’s no danger of a general outbreak, if that’s what you’re thinking. No danger of that at all.” Ain't that a turn of phrase. Also here's Crook.  We'll see what comes from this infodump... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:Elspeth and I were going in to dinner at the Grand Pacific, and I had turned into their big public lavatory to comb my whiskers or adjust my galluses; I was barely aware of a largish man who was examining his chin closely in a mirror and grunting to himself, and I was just buttoning up and preparing to leave when the humming ended in a rasping growl of surprise.  quote:He nodded vigorously. “The Spotted Tail. Hinteh,c how long has it been? You have grown well, Wind Breaker – with a little frost in your hair.” He pointed to the grey in my whiskers, chuckling. Smart as paint would nowadays be more clearly stated as 'Bright as a fresh coat of paint." quote:But I couldn’t get over our strange meeting, and as we walked to the dining-room I demanded to know what he’d been doing, and where he’d learned English – not that he had much. Spotted Tail certainly seems one to make the most of life's few bright spots. This enchanted evening will continue... next time.

|

|

|

|

Anyone who claimed that Fraser's prose was exceptionally good or praised it in this thread should read The Reavers. I do hope we'll at least get to quote a few chosen passages as an interlude between Flashman books (and also do an actual readthrough of Black Ajax, though censoring out all the racism would be a chore).

|

|

|

|

Xander77 posted:Anyone who claimed that Fraser's prose was exceptionally good or praised it in this thread should read The Reavers. I do hope we'll at least get to quote a few chosen passages as an interlude between Flashman books (and also do an actual readthrough of Black Ajax, though censoring out all the racism would be a chore). it sounds like the reavers is him writing a dumb book on purpose? the excerpts in the NYT review sound a little sub-pratchett, how does the book hold up?

|

|

|

|

sebmojo posted:it sounds like the reavers is him writing a dumb book on purpose? the excerpts in the NYT review sound a little sub-pratchett, how does the book hold up? A lot of reviewers think he's aiming at Pratchett, MST, or (if less charitable) Seltzer and Friedberg. Personally, I peg Fraser as someone who hasn't be paying attention to popular media since at least the 1980's, and the gag style as taken directly from 1960's pulp spy parodies. Run on sentences that keep piling on quote:Rumours abounded that His Majesty was already being fitted out with tropical kit, Scottish courtiers were practising drawls and trying to stop saying “Whilk" and “umquhile,” the Scottish National Party were preparing banners reading “Home Rule in England” and “It’s Scotland’s Cheddar!,” London merchants were taking options on supplies of Japanese haggis, and Home Counties landowners were preparing to turn their estates into golf courses. But alle was uncertayne, and remayned to be seene. quote:Their mouths parted with a long, lingering squelch, and through a cinnamon mist in which dark eyes and lambent moustache still glowed, Lady Godiva came to herself and saw, in dishevelled bewilderment, that her erstwhile lip-ravisher was back in his seat with a jeweller's glass screwed in his eye, examining — nay, it could not be! — her priceless necklace (yes, it's the Dacre Diamonds, that fabulous collar nicked by Sir Acre Dacre from the harem of Suleiman the Improbable in the Third Crusade), her emerald earrings, sapphire fillet, pearl brooch, gold rings, and even her platinum zip-fastener, dammit! Dumbstruck Kylie was giving a creditable impersonation of a Black Hole — and now the gorgeous swine was slipping the lot in his pocket and regarding his victim with heavy-breathing admiration. Xander77 fucked around with this message at 07:46 on Jun 22, 2022 |

|

|

|

Yeahhhh

|

|

|

|

That’s some real Man From ORGY writing. Flashback to when I was 12 or so:

|

|

|

|

Remulak posted:That’s some real Man From ORGY writing. Flashback to when I was 12 or so: That insight into 40 year old Fraser's fap material is fairly unwelcome.

|

|

|

|

Yeah, I was deeply unimpressed with The Reavers, Captain In Calico, and The Pyrates, but I quite liked Black Ajax. Frasier was a brilliant satirist, but less skilled at farce. I had the same problem with the Royal Flash movie - it leaned way too far into farce. However, his non-fiction history of the reavers, The Steel Bonnets, was quite good...if a little biased. At one point, he describes a massacre of about 200 Scotsmen, all members of criminal clans, as "one of the most comprehensive and cruel examples of race persecution in British history".

|

|

|

|

quote:He even had a table reserved, with his followers already installed: a couple of young braves dressed civilized like himself, and a third with a coloured blanket over his shoulders, so it was hard to tell whether he was in faultless dinner rig underneath or not – he wore no shoes, though. But what took me aback was that there were two squaws (both wives of the chief’s) in fringed tunics, the whole party seated poker-faced at a large round table, heedless of the whisperings and amused glances of the civilised folk at neighbouring tables. It is a shame that Elspeth never has as much of a role as she did in Flashman's Lady, just her presence makes scenes better. quote:That sent her into trills of laughter, and Spotted Tail beamed and patted her arm; aye, thinks I, we must look out here. The young squaw beyond Elspeth evidently thought so too, for with an artless curiosity she leaned forward and began to finger Elspeth’s necklace and earrings, murmuring with admiration. Women being what they are, in a moment they were comparing beads and materials; Spotted Tail sighed and turned to me, so I asked him what had become of his small nephew, the Fair-Haired Boy. He sat back in astonishment.  Everyone was a baby at some point. quote:I said I’d heard his name for the first time that afternoon – and recalled in wonder the laughing mite I’d carried on my saddle. Well, I’d said in jest that he’d be a great man some day; now, I said, the Isantanka chiefs spoke of him as a maverick, the most hostile of Indians.54 Author's Note posted:This seems to represent Spotted Tail’s philosophy very fairly. A remarkable man, the Brulé chief was considered the Sioux nation’s foremost warrior in the 1840s and 50s; he was credited early in his career with counting 26 coups, and by the end of his life had more than a hundred scalps on his war-shirt. Following the wipe-out of Lt Grattan and his troops by the Brulé under their chief Bear-that-Scatters in 1854, Spotted Tail and four other braves agreed to “give their lives for the good of the tribe”, and surrendered, singing their death-songs. Spotted Tail was imprisoned at Fort Leavenworth, where he is said to have learned some English, and where his observations seem to have convinced him that it was futile to attempt resistance to the white man. Later, as chief of the Brulés, he was a resolute champion of peace and reconciliation and, says his biographer Hyde, obtained advantages for the Sioux by persuasion which their militant leaders failed to win by war: “He was probably the greatest Sioux chief of his period … (and) played his part better than any of the other Sioux leaders.”  I can see why Flash should be worried. We'll see where the evening takes them all... next time.

|

|

|

|

Grendel posted:Yeah, I was deeply unimpressed with The Reavers, Captain In Calico, and The Pyrates, but I quite liked Black Ajax. Frasier was a brilliant satirist, but less skilled at farce. I had the same problem with the Royal Flash movie - it leaned way too far into farce. I also didn't care especially for the Pyrates or the Reivers. Not so much I thought they were badly done, as because they mostly referenced a period of classic films I haven't the same memories of and affection for that he clearly did. I agree that Royal Flash film was dire. My brother and I were so disappointed when we heard about it as teenagers and tracked a copy down! For anyone who hasn't seen it, it's Malcolm McDowell as Flashy, who is a good actor but must have been 10 stone soaking wet (140 pounds, or about 64kg) and was not plausible as a cad disguised as Victorian hero. It was mostly Bismarck's 3 goons chasing him around, more like the 3 stooges.

|

|

|

|

quote:After dinner he insisted that we accompany him to the theatre, taking Elspeth’s hand and positively pleading with her through me as interpreter. I translated those compliments which were fit for her ears, with the result that presently we were bowling off in a cab, with Spotted Tail up beside the driver in a tile hat, roaring at him to go faster. The squaws and blanket chap were left behind, and Elspeth and I shared the inside of the cab with the other two, fine young bucks named Jack Moccasin and Young Frank Standing Bear, who sat with their arms folded in grave silence. Elspeth confided to me that Standing Bear was quite distinguished-looking, and had an air of true nobility. Ah, these two dance so beautifully. quote:I was thankful that Elspeth didn’t understand Siouxan; so far as she knew I’d crossed the Plains with a company of farmers and Baptists who said prayers night and morning. I was also pleased to learn that Spotted Tail was leaving next day; I didn’t tell Elspeth that he had compared her favourably, and in indelicate detail, with the female performers at the theatre, but there was no mistaking the enthusiasm with which he pressed her hand on parting – or the fact that the vain little baggage went slightly pink, lowering her eyes demurely and positively purring. The deuce with this, thinks I, there’ll be no more noble savages on this trip. And then: Married three-and-a-half decades at this point. quote:“Do you think it would be efficacious? If so, I should be most obliged to you, Harry, for I have read that it is beneficial, and I think I should not care to be too plump … Oh, you designing wretch! What deceit! No, now, desist this minute, for I see you are not really interested in reducing me at all—” Well, with that scintillating passage the chapter ends. Let's see how he gets dropped in it... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:Naturally I did my best to wriggle out of it next day, since the artful baggage had taken such unfair advantage of me, first provoking my jealousy and then my ardour, stirring her rump before the mirror – did I think she was hopa, forsooth – and extracting a half-promise when she had me in extremis. And she called me designing! And all because she had taken a passion for that damned Sioux, what with his feral charm and her nursery dreams of noble savages, forgotten while she’d had the social circus of Boston to distract her butterfly brain. They had revived under his smouldering regard, and I guessed she was having delicious shivers at the thought of him sweeping her off at his saddlebow and having his wicked will of her by the shores of Gitchee-Gummee. She’d been just the same with that fat greaser Suleiman Usman, who had filled her head with twaddle about being his White Jungle Queen – well, I wasn’t risking that again. The trouble with Elspeth, you see, is that while I doubt if she really wants to be abducted and ravished by hairy primitives – well, not exactly – she’s such a congenital flirt that she sometimes gets more than she bargains for.  Wait no, that's not it... quote:It was the land they enclosed that was the trouble, for while the boats and trains might run round its limits, there wasn’t much going through it, not in a hurry. This was the last stamping-ground of the Sioux, the biggest and toughest Indian confederacy in North America, a greater thorn in Washington’s side than even my old friends the Apaches of the south-west. Fifty thousand Sioux, Sherman had reckoned, and their allies the Northern Cheyenne, first cousins to those stone-faced giants I’d met on the Arkansas. In those days the Sioux had been lords of the prairie from the Santa Fe Trail to the British border, from Kansas to the Rockies, tolerating the wagon-trains (give or take a raid now and then) and rubbing along quietly enough with the few troops that the Americans sent into the West.  No, not that either... quote:By 1875, though, it looked as though the thing must peter out at last; hunters and sportsmen had swept the buffalo off the prairie at a rate of a million a year, until they were all but extinct – and the Indian without buffalo is worse off than the Irish without the potato, for it’s clothing and lodging to him as well as food. Plainly even the wildest hostiles would have to chuck it and settle down soon; the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, which would inevitably mean the loss to the tribes of yet another stretch of territory, must only hasten the process, for it would leave them little except the barely-explored fastness south of the Yellowstone called the Powder River country, and with game so scarce they would have to call it a day or starve. That was the general view, so far as I could gather, and with it went the opinion that I’d heard from Sheridan: however it ended, there wouldn’t be a war. An ugly incident or two here and there, perhaps – regrettable, but probably inevitable with such people – but no real trouble. No, sir.  Is there seriously no fancy gif of the expansion of rail lines on the continental US to be found anywhere? Oh. Uh, Grant next time...

|

|

|

|

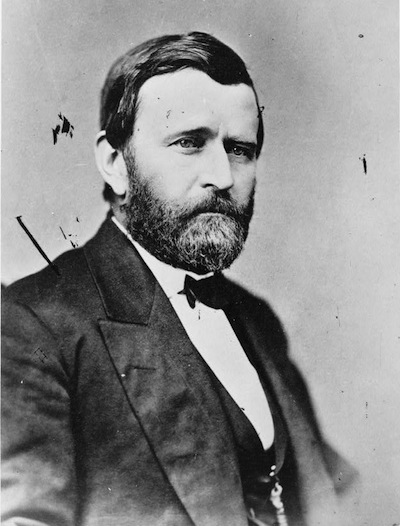

quote:Washington, a dismal swamp at the best of times, was sweaty and feverish, and so were its inhabitants, with Grant’s presidency soon to enter its final year and the whole foul political crew in a ferment of caballing and mischief. Any gang of politicos is like the eighth circle of Hell, but the American breed is specially awful because they take it seriously and believe it matters; wherever you went, to dinner or an excursion or to pay a call, or even take a stroll, you were deafened with their infernal prosing – I daren’t go to the privy without making sure some seedy heeler wasn’t lying in wait to get me to join a caucus. For being British didn’t help – they would just check an instant, beady eyes uncertain, and then demand to know what London would think of Hayes or Tilden, and how was the Turkish crisis going? (This at a time when Grace was making triple centuries in England, and I not there.)     Yeah, it'll do that. quote:I said something soothing about the cares of state. “Not a bit of it,” barks he. “It’s this infernal hand-shaking. Do you realise how frequently the office demands that the incumbent’s fingers shall be mauled and his arm jerked from its socket? No human constitution can stand it, I tell you! Pump-pump-pump, it’s all they damned well do. Ought to be abolished.” Still happy old Sam, I could see. He growled and asked cautiously if I was staying long, and when I told him of our projected trip across the Plains he chewed his beard moodily and said I was lucky, at least the damned Indians didn’t shake hands. Oh Flash, you do it to yourself. quote:One of those remarks, I agree, which will stop any conversation in its tracks. Allison stared, and a silence fell, broken by Grant’s rasping question. “What’s that, Flashman? Do you happen to be an authority on the Indian calendar?” And away they goooo. I thought I remembered a very different interatction between Grant and Flash in this book but it turns out that's from #11. We'll, off to it... next time!

|

|

|

|

I am always sad that we will never get to read about what Flashman got up to during the Civil War. I think all we know is that he fought for both sides, and was liked by both Lee and Grant.

|

|

|

|

Cricket: Slight Returnquote:(This at a time when Grace was making triple centuries in England, and I not there.) Dr W.G. Grace was often reckoned the greatest cricketer of all time until Bradman came along a couple of generations later, and one of the few men whose image transcends the sport. Primarily a batter who was still useful with the ball, he was a comic-book figure come to life, with a hefty frame and massive beard. He played in 44 straight first-class seasons, and was particularly renowned for his undying commitment to bending the rules without actually cheating (one possibly-apocryphal story tells of how he reacted to being given out LBW by telling the offending umpire that the suitably large crowd had come to watch him bat, not the umpire give him out), and his thoroughly shameless ability to make vast sums of money for playing cricket while also claiming to be an amateur. Flashy would surely have been a big fan, in a jealous way. A century is when a single batter makes 100 runs in the same innings. In the modern game it's still a noteworthy achievement but top batters are expected to make them; in Grace's time they were relatively rare and cause for great celebration. Playing in an era when pitches were far worse and batting far harder, he was the first player to make a century of first-class centuries in his career (the exact figure is disputed by historians; the most common total has him 10th out of 23 to reach that mark). In August 1876 he made 344 for MCC against Kent, the first batter to score a first-class triple century, and then two weeks later he did it again with 318 not out for Gloucestershire against Yorkshire. 344 stood as the individual record until 1895, and it has only been beaten six times after that.

|

|

|

|

withak posted:I am always sad that we will never get to read about what Flashman got up to during the Civil War. I think all we know is that he fought for both sides, and was liked by both Lee and Grant. Seriously. One of the great unwritten books in my awareness. Also would have been almost as ripe for Arbite's commentary as Flash for Freedom!

|

|

|

|

quote:As it turned out, I wasn’t – of service, I mean – but I take no blame for that. Solomon himself couldn’t have saved the Camp Robinson discussions with the Sioux from being a fiasco, not unless he’d gagged Allison to begin with. There is some natural law that ensures that whenever civilisation talks to the heathen, it is through the person of the most obstinate, short-sighted, arrogant, tactless clown available. You recall McNaghten at Kabul, perhaps? Well, Allison could have been his prize pupil. This loving guy. quote:Even before we set out, the omens were bad. The peaceful agency tribes were fractious because in the hard winter just past they’d been kept short of the necessaries government should have been providing – one of the reasons Spotted Tail had been east in June was to complain. In his absence his younger braves had worked themselves into a frenzy at the annual sun dance and gone off for a slap at the Black Hills miners (and at their old foes the Pawnees, just for devilment); there had been a nasty brush between the Brulés and Custer’s 7th Cavalry, and when Spotted Tail returned it had taken all his influence and skill to bring his bucks to heel. Racism by ignorance meets racism by familiarity. quote:The fort itself was a fairly spartan affair of wooden houses and barracks, but Anson Mills, the commandant from Camp Sheridan, was on hand with his wife to make us welcome, and Elspeth was far too excited to mind the absence of city comforts. What indeed. Well, we shall learn more... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:“Nothing,” says I. “I’m here because I know you and speak your tongue.” Flashman at ease and not being a malicious rear end. Stange days. quote:“These talks are a sham,” I continued, “and you know it. The Black Hills are gone, and you’ll never get ’em back. This lot won’t leave you a rag to your back if you resist them. So isn’t it time to get the best bargain you can? And make those mad bastards up in Powder River country understand that they’d better settle for it, or they’ll get worse? I’m not saying it’s right or fair; that don’t count. I’m just saying it’s common sense. And you know it, too.” Flash has always been presented as clear sighted but is rarely able to share his views without some consideration to his position relative his audience. quote:It was then, I think, that he began to believe if not necessarily to trust me. As why shouldn’t he, since I’d been telling truth straighter than I could ever remember? At any rate, he finally nodded, and said he would wait and see what was said publicly tomorrow. Almost as an afterthought, as he was about to go, he says conversationally: Pro pelle cutem is the motto of the Hudson's Bay Company, which had been operating for over two centuries at this point. Being better than the Americans at treating the native population is not an acceptable bar to clear. Well, more exploitation to come... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:He did, too, the following day, when Spotted Tail got up in full council and blandly announced the price of the Black Hills: forty million dollars. I didn’t believe my ears, and watched with interest as I translated, for it’s not every day that you see a senatorial commission kicked in its collective belly. D’you know, they never blinked – and my suspicious hackles rose on the spot. There was a deal of huffing and consideration before Allison replied at judicious length, but all his palaver couldn’t conceal his point, which was that the government were prepared to offer only six million, and over several years at that. There was much nonsense about renting and leasing, in which Spotted Tail showed politely satirical interest, but now that he’d seen the dismal colour of their money it was so much waste of time; he concluded that they had best put it in writing, and stalked out. Red Cloud, by the way, hadn’t bothered to attend. Allison seems to be reminding him of Bismarck whose refusal to budge on the amount of money offered helped convince Flash that the business in Strackense might not end with him dead. quote:Spotted Tail welcomed us outside the fine frame house which the army had set aside for his use at Camp Sheridan, but after showing us round its empty rooms with a proprietorial pride, he explained gravely that he didn’t live here, but in a tipi close by. The advantage of this was that when the tipi got foul he could move it to a clean stretch of ground some yards away (like the Mad Hatter at the tea-party), a thing he could hardly have done with a two-storey house. What, clean the floors? He shook his head; his squaws wouldn’t know how. Somehow this seems even more pig-headed then the when the British was punting own goal after own goal in the leadup to the mutiny. quote:Sure enough, it was on the morning of the assembly that we got the first whiff of mischief. At Red Cloud’s request the meeting was to take place out on the open prairie, some miles from the fort, where the Indian thousands could congregate conveniently, and we had already piled into the ambulance, with Anson Mills’s two cavalry troops flank and rear, and Elspeth and Mrs Mills waving from the verandah, when there was a shout from across the parade, and here came a party of mounted Indians, armed and in full paint, cantering two and two and led by a stalwart Oglala, Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses, whom I’d seen in Red Cloud’s entourage. As he rode up to Anson Mills, I noticed young Standing Bear in war-bonnet and leggings, with lance and carbine, at the head of one of the lines; I beckoned him to the tailboard and asked him what was up. I wonder how precisely one can date the government of the United States' opinion on the greater indigenous population shifting from 'great potential threat best handled with care' to 'nuisance that can be easily handled at some expense.' Anyway, we'll see what comes of this speech... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:Allison got to his feet and cleared his throat, shooting nervous glances at the silent red assembly twenty yards off, and at that moment I noticed movement on the outer wings of the crowd. Mounted warriors were cantering in towards us, either side; they swept wide to outflank the canopy, and trotted in behind Mills’s two lines of troopers. I screwed round to watch, my hair on end, as the two long files of painted braves, lances and guns at the ready, took station behind our cavalry – by God, they were marking ’em, man for man! Ten feet behind each trooper there was now a mounted Sioux, and there was no doubting the menacing significance of that. Allison stammered over the first few words of his address, and ploughed on, and I was preparing to translate aloud when a harsh voice cut in before me – a half-breed among the Indians was translating. So they’d brought their own interpreter with them; that might be significant, too. Two books from now we'll see even more explicit sabotage of one's own responsibility. This whole business isn't even mentioned on Allison's wikipedia article. quote:One thing was clear: he hadn’t made it any easier for Red Cloud and Spotted Tail to accept with dignity. Red Cloud was getting to his feet, his face a grim mask; as he raised a hand to the assembly and faced the commission, silence fell again; he pushed back the trailing gorgeous wings of his war-bonnet and fixed us with his gleaming black eyes. Oh for God's sake. quote:“Why, I have come to see the great pow-wow!” cries the blonde lunatic. “My, what a splendid sight! What are they calling out for? Oh, see, there is Mr Spotted Tail! But I declare, Harry, I never knew there were so many—” Yeah, she's not showing her best features at this particular moment. We'll see how this incitement ends... next time!

|

|

|

|

One thing Fraser does insanely well is to capture that rising dread as a situation goes from innocuous to cautious to alarming to dangerous to horrific. He plays with doing it at different speeds but for my money he’s best at the slow burn.

|

|

|

|

|

quote:There was nothing to be done about that; with Standing Bear knee to knee I urged my beast up against the canvas cover as the ambulance rolled away. We were surrounded by a phalanx of Mills’s bluecoats, with Young-Man-Afraid and his braves among them. Thank God Mills was cool, and every sabre was in its sheath. All round was a disordered, threatening mob of Indians, yelling taunts, but the ambulance was moving well now, its horses at the trot; it trundled under the trees and out on to the trail to camp, towards the big buttes, and I swallowed my fear and looked about me. A pity to see bloodlust sated on the innocent, but... quote:The Sioux fell away after that, and we rolled on to the camp in safety, Mills sensibly holding one troop behind as rearguard while the other took the ambulance ahead. I stayed with him, since it always looks well to come in with the last detachment, scowling back towards the danger; it was safe enough now, and I knew that Elspeth was all right with the commission. Mills was thorough; he pulled up a mile from camp and we waited an hour while Young-Man-Afraid’s chaps scouted back; they reported that the Sioux were dispersing to their tipis, and Little Big Man’s hostiles had withdrawn. All was quiet after the sudden brief excitement, but I guessed it had been a damned near thing. Haaah, these two. quote:Instinctively I clamped her to me, shuddering. A big whoop indeed. Let's get more of the aftermath... next time!

|

|

|

|

Elspeth is the best.

|

|

|

|

quote:I choked as I held her, and asked what had happened. Keep your pants on. quote:“Oh, he showed me to such a pretty little grove, with a tent, where I should be comfortable while he went to business with his friends. But presently he came back and we chatted ever so comfortably. Well,” she laughed gaily, “he tried to chat, but it was so difficult, with his funny English – why, almost all he knows is ‘Joll-ee good!’” Happy to serve as escorts, I'm sure. quote:What the devil was I to say? I’d no positive evidence (just plain certainty), and if I accused her, or even voiced suspicion, there would be indignation and floods of tears and reproach … I’d been through it all before. Was I misjudging her by my own rotten standards? No, I wasn’t either – I knew she was a trollop, and her wide-eyed girlishness was a deliberate mockery. Wasn’t it? No, blast it, it wouldn’t do, I’d have it out here and now—” Huzzah! And that's the end of that chapter.

|

|

|

|

Those two are great

|

|

|

|

They so deeply deserve each other.

|

|

|

|

|

What an amazing woman.

|

|

|

|

quote:If, as I strongly suspect, that turbulent afternoon’s work was a pleasant consummation for Lady Flashman and Chief Spotted Tail, it wasn’t for anyone else. The Black Hills treaty died then and there, slain by Senator Allison and Little Big Man. There followed another meeting at Camp Robinson – which I didn’t attend because I’d have exploded in his presence – at which Spotted Tail announced the Sioux’s formal rejection of the offer; Allison warned him that the government would go ahead anyway, and fix the price at six million without agreement, but the most they could get from him was a promise to send word of the offer to Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and if they accepted it then he and Red Cloud would give it their blessing. Which was so much eyewash, since everyone knew the hostiles wouldn’t accept. Standing Bear was to be the ambassador to the hostile chiefs, since he was apparently a protégé of Sitting Bull’s and well thought of by him.  It's never the right senator who gets caned within an inch of his life. quote:I’ve wondered since how much either side really wanted a treaty. I believe Red Cloud and Spotted Tail were ready for any terms that even looked honourable, and if Allison had been more tactful and offered a half-decent price, they might have won over enough Sioux to make the opposition of the hostile chiefs unimportant. I don’t know. What I can say is that the Indians went away from Camp Robinson in bitter fury, and while Allison was personally piqued I’m not certain he was altogether surprised, or that Washington minded too much. I’ve wondered even if the commission wasn’t simply a means of proving how stubborn the Indians were, and puting ’em in the wrong; perhaps of testing their mettle, too. If so, it failed disastrously, for it led Washington and the Army to draw a fatally wrong conclusion: after Camp Robinson it became accepted gospel that whatever happened, the Sioux wouldn’t fight. I confess, having seen the way they didn’t cut loose at the grove, it was a conclusion I shared. A hundred years of vexing the British in ways great and small, among the lesser crimes. quote:1876 being the hundredth anniversary of the glorious moment when the Yankee colonists exchanged a government of incompetent British scoundrels for one of ambitious American sharps, it had been decided to celebrate with a grand exposition at Philadelphia – you know the sort of thing, a great emporium crammed with engines and cocoa and ghastly bric-à-brac which the n****** have no further use for, all embellished with flags and vulgar statuary. Our princely muffin the late Albert had set the tone with the Crystal Palace jamboree of 1851, since when you hadn’t been able to stir abroad without tripping over Palaces of Industry and Oriental Pavilions, and now the Yankees were taking it up on the grand scale. Elspeth was all for it; she suffered from the common Scotch mania for improvement and progress through machinery and tracts, and had been on one of the Crystal Palace ladies’ committees, so when she fell in with a gaggle of females who were arranging the women’s pavilion at Philadelphia, it was just nuts to her. She was in the thick of their councils in no time – republican women, you know, love a Lady to distraction – and there could be no question of our going home until after the opening in May. Author's Note posted:The great Philadelphia Centennial exhibition was opened on May 10, 1876, at Fairmount Park, by President Grant. The foreign contributions included a belly-dancer from Tunisia, but it is unlikely that she was sponsored by the ladies’ committee, whose work was on an altogether more serious level. (See Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition, reproduced in 1974 with an introduction by Richard Kenin.)  Ah, the scandal! We'll get some of Flashman flummoxed and some reunions too... next time! Arbite fucked around with this message at 04:26 on Aug 29, 2022 |

|

|

|

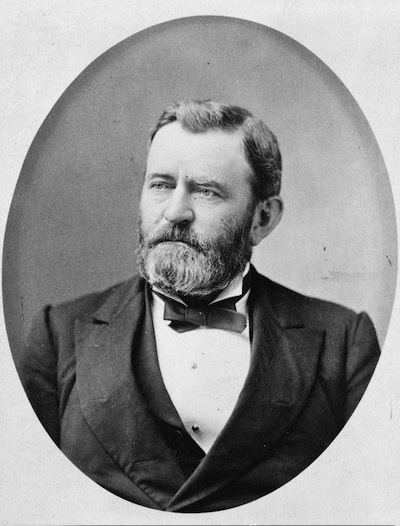

quote:Mostly, though, we were in and about the smart set, and New York society being as small as such worlds are, the encounter which I had just after Christmas was probably inevitable. It happened in one of those infernal patent circular hotel doors; I was going in as another chap was coming out, and he halted halfway, staring at me through the glass. Then he tried to reverse, which can’t be done, and then he thrust ahead at such a rate that I was carried past and finished where he had been, and he tried to reverse again. I rapped my cane on the glass.  I would love to see how many practical props those old photo studios tended to have, as you can see with his hat resting there, vs amount of backdrops. quote:“Whatever brings you to New York?” cries he, pumping my fist. “Why, it must be ten years – say, though, more than that since our encounter at Audie! But this is quite capital, old fellow! I should have known those whiskers anywhere – the very picture of a dashing hussar, eh? What’s your rank now?”  Yeah, she looks the type to launch a decades long misinformation campaign. quote:I wasn’t sure it was, as I watched him striding off through the falling snow. Aside from the Audie skirmish, Appomattox, and an exchange of courtesies in Washington, I’d hardly known him except by reputation as a reckless firebrand who absolutely enjoyed warfare, and would have been better suited to the Age of Chivalry, when he’d have broken the Holy Grail in his hurry to get at it. And while I’d met scores of old acquaintances in America, for some reason running into Custer recalled my meeting with Spotted Tail, with its uncomfortable consequences. Oh yeah, this is definitely the guy you want to keep the peace out on the frontier. Sheesh. We'll see Flashman poke the sobbing sober sod... next time!

|

|

|

|

Arbite posted:... Really glad this is still going! What do you mean about Custer's wife/widow and a disinformation campaign? Was she a leading disseminator of some sort of idea that the Sioux started it, or that he didn't make a colossal tactical blunder?

|

|

|

|

Custer was a huge mess of a person. He lost a lot of people’s money in crazy investments, shoved his nose into politics and made a bunch of enemies for now reason, constantly played nepotism games out of anguish about his rank, stole and deserted and was court marshaled twice, and constantly cheated on his wife. The only thing good about him was how well he could ride and fight, which saved his bacon after multiple blunders. Until it didn’t b

|

|

|

|

quote:“Ah, but you British are lucky!” cries he, after he’d mopped himself and they’d brought him a fresh salad. “When I reflect on the contrasting prospects of an aspiring English subaltern and his American cousin, my heart could break. For the one – Africa, India, the Orient – why, half the world’s his oyster, where he can look forward to active service, advancement, glory! For the other, he’ll be lucky if he sees a skirmish against Indians – and precious thanks he’ll get for that! – and thirty years of weary drudgery in some desert outpost where he can expect to end his days as a forgotten captain entering returns.”  1... 2... Well look at that! Who's this? Wikipedia posted:(Pictures taken shortly after the battle show a scar "with minor soft tissue damage to his lower jaw extending to a point just below the right ear"; though the wound to Tom's face was across blood-rich tissue and covered him in his own blood, had the bullet gone through the mouth or the soft tissue of the neck it would have likely struck a major vessel and have caused him to bleed to death.) Having captured the flag Custer held it aloft and rode back to the Union column. An officer of the Third New Jersey cavalry, seeing Custer ride back with the banner flapping, tried to warn him that he might be shot by his own side: "For God's sake, Tom, furl that flag or they'll fire on you!" Custer ignored him and kept riding towards his brother Armstrong's personal battle flag and handed the captured flag to one of Armstrong's aides while declaring, "Armstrong, the damned rebels shot me, but I've got my flag." Custer turned his horse to rejoin the battle, but Armstrong (who had only seconds before seen another of his aides be shot in the face and fall from his horse dead) ordered Custer to report to the surgeon. Tom ignored the order and his brother placed him under arrest, ordering him to the rear under guard. Hah, peas in a pod. quote:“They send ’em up with the rations, anyway,” says I, lamely, and Elspeth, who is the most well-meaning pourer of oil on troubled flames I know, launched into a denunciation of the way Jealous Authority invariably overlooked the Claims of the Most Deserving, “for my own gallant countrymen, Lord Clyde and Sir Hugh Rose, were never awarded the Victoria Cross, you know, and I believe there were letters in the Herald and Scotsman about it, and Harry was only given his at the last minute, isn’t that so, my love? And I am sure, General Custer,” went on the amazing little blatherskite with awestruck admiration, “that if you knew the esteem in which your name and fame are held in military circles outside America, you would not exchange it for anything.”   Eesh. quote:We saw a good deal of the Custers that winter, for although he wasn’t the kind I’m used to seek out – being Puritan straight, no booze, baccy, or naughty cuss-words, and full of soldier talk – it’s difficult to resist a man who treats you as though you were a military oracle, and can’t get enough of your conversation. He was beglamoured by my reputation, you see, not knowing it was a fraud, and had a great thirst for my campaign yarns. He’d read the first volume of my Dawns and Departures, and was full of it; I must read his own memoirs of the frontier which he was preparing for the press. So I did, and said it was the finest thing I’d struck, beat Xenophon into a cocked hat; the blighter fairly glowed. How nice, somebody actually wants the Sioux around. Christ. We'll get a few false starts on departing... Next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:“You’re sure he’ll fight, then?” Not a lot of wracked up dept in the Flashman stories, mostly just worrying about the width of funnel from which cash pours. quote:“God bless you, old fellow,” says he, and off he went, much to my relief, for he’d given me a turn by suggesting active service, the dangerous, inconsiderate bastard. ’Tain’t lucky. I hoped I’d seen the last of him, but several weeks later, sometime in April, when Elspeth was off in the final throes of her Philadelphia preparations, I came home one night to find a note asking me to call on him at the Brevoort. I’d supposed him far out on the prairie, inspecting ammunition and fly-buttons, and here was his card with the remarkable scrawl: “If ever I needed a friend, it is now! Don’t fail me!!” He's scammed around, not through, or so his supportes (and most historians) say. quote:“What do you know about it?” snaps he. “Oh, forgive me, old friend! I am so distraught by this – this web they’ve spun about me –” Oh ho? Author's Note posted:This gossipy summary of the Belknap case is true enough in its essentials, but what is still not clear is Custer’s motive in giving evidence at the time. He did have high political ambitions, and the corruption of the administration was no doubt a tempting target. But he was probably sincere in not wanting to leave his command to testify in person, for purely military reasons – and possibly also because he feared the consequences of embarrassing Grant at that particular moment. It was, perhaps, a question of timing – and Custer’s sense of timing could be deplorably bad. (For details of Custer’s correspondence with the Clymer committee, who summoned him to Washington, see A Complete Life of General George Armstrong Custer, by Frederic Whittaker, 1876; Dunn.) Hah, oh dear. Incidentally, that's the book his wife supported in her early efforts to polish his image. We'll see the more of that sour man and enjoy a fine bit of Flashman and literature colliding... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:“He means to break me!” cries Custer. “I know his vindictive spirit. By his orders I am kept in Washington, like a dog on a lead, at a time when my regiment needs me as never before! It’s my belief Grant intends I shall not return to the West – that his jealous spite is such that he will deny me the chance to take the field! You doubt it? You don’t know Washington, that’s plain, or the toads and curs that infest it! As though I cared a rap for Belknap and his dirty dealings! If Grant would see me I would tell him so – that all I want is to do my duty in the field! But he refuses me an audience!” What, no mention of McClellan? quote:He stood working his fists, his face desperate. “You’re my best hope – my only one! I beg of you not to fail me!” Author's Note posted:Tight waists were a fashionable joke at this time. Punch has a cartoon of three ladies who have dressed for the evening on the understanding that they will not even have to climb the stair. A cursory glance around didn't locate this image, anyone else have luck? Anyway, without interruption, my favorite scene in the book: quote:From that exotic vision to the surly bearded presence of Ulysses S. Grant was a most damnable translation, I can tell you. I had endured Custer’s rantings on the way down – release from Washington and return to his command were what I was expected to achieve – and while it seemed to me that my uncalled-for Limey interference could only make matters worse, well, I didn’t mind that. I was quite enjoying the prospect of playing bluff, honest Harry at the White House, creating what mischief I could. When Ingalls, the Quartermaster-General, heard what we’d come for, he said bluntly that Grant would have me kicked into the street, and I said I’d take my chance of that, and would he kindly send in my card? He clucked like an old hen, but presently I was ushered into the big airy room, and Grant was shaking hands with fair cordiality for him. He thanked me again for Camp Robinson, inquired after Elspeth, snarled at the thought that he was going to have to open the Philadelphia exhibition, and asked what he could do for me. Knowing my man, I went straight in. Author's Note posted:President Grant was an admirer of Tom Brown’s Schooldays and its author, Thomas Hughes, the Radical MP and social reformer, who (like his book) became extremely popular in the United States – Hughes even helped to found a model community in Tennessee, which was christened Rugby, after his old school. During Grant’s visit to England in 1877, Hughes proposed the former President’s health at a private dinner at the Crystal Palace; Grant had been told that a speech from him was not expected, but he insisted on rising to express his gratification at hearing “my health proposed in such kind words by Tom Brown of Rugby”. That was just lovely. And he doesn't see through Flashman but isn't overawed. Right up until the end, anyway. We'll get Custer's reaction to all of this... next time!

|

|

|

|

Arbite posted:What, no mention of McClellan? Flashman's adventures in the civil war really is one of the great unwritten novels, for my money. The fact he served on both sides, he had the Medal of Honour, that great line from Lincoln . . . we will always wonder what happened.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 5, 2024 20:09 |

|

quote:I strolled out, and Custer leaped from ambush, demanding news. With a temperament like that it's a wonder he didn't reach theater command. quote:I ambled back to the hotel, whistling, and found a note at the porter’s cabin; Grant wanting me to autograph his copy of Tom Brown, no doubt. But it wasn’t. A very clerkly hand: Curious tick. quote:If there’s one thing I can tolerate it’s a voluptuous beauty who expected me to be older. I was still recovering from my surprise, and blessing my luck. At point-blank she was even more overpowering than I’d have imagined; the elegant severity of the dress which covered her from ankle to chin emphasized her figure in a most distracting way. It was abundantly plain that her shape was her own, and certainly no corset – they were thrusting across the desk of their own free will, and the temptation to seize one and cry “How’s that?” was strong. No encouragement, though, from that commandingly handsome dark face with the crimson strip cutting obliquely across brow and cheek; the fleshy mouth and chin were all business, and the smile coldly formal. The high colour of her skin, I noticed, was artfully applied, but she wore no perfume or jewellery, and her hands were strong and capable. In a word, she looked like a belly-dancer who’s gone in for banking. They would have a bit of a 'Not before I see you' encounter not too long after this, though. We'll see where this mysterious beauty takes the conversation... next time!

|

|

|