|

Book reviews due at midnight tonight!

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 9, 2024 09:43 |

|

Ended up having less time to work on this than I was expecting to. Life sucks work sucks. Anyways my book is Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, by Edward Herman and everyone's new favorite Biden supporter Noam Chomsky. The text lays out the following argument: quote:[T]he media serve, and propagandize on behalf of, the powerful societal interests that control and finance them. The representatives of these interests have important agendas and principles that they want to advance, and they are well positioned to shape and constrain media policy. This is normally not accomplished by crude intervention, but by they selection of right-thinking personnel and by the editors' and working journalists' internalization of priorities and definitions of newsworthiness that conform to the institution's policy. Emphasis mine. In order to demonstrate this, Herman and Chomsky lay out their structure of a propaganda model for the media and, via a series of case studies, explain how this model determines the performance of the media and how its reporting is shaped. This model stands in stark contrast to the model the media claims to represent: that of the purely objective observer, dryly reporting on the events of the day and leaving analysis, interpretation, and the final determination to the individuals receiving the reporting. Instead, the text will argue that the media engage in "manufacture of consent," a term the authors borrow from Walter Lippmann, who was writing on the subject of the shaping of public opinion in the early 1920s and argued that propaganda was already then becoming central to the normal operation of government. In the preface to the text the authors also take a moment to explain that while it is easy to dismiss this model as no more than a conspiracy theory, it isn't a fair engagement with the argument being made. As mentioned in the quote above, the model doesn't assert that there is some central guiding force dictating what is seen and heard; the authors don't lay the blame at the feet of the Illuminati or the Bilderberg Group as the sole arbiters what may be said. But rather that there are forces at play that, often through free market principles, put pressure on the media to conform to certain standards and to practice self-censorship. And they further state that the media is not monolithic: quote:Where the powerful are in disagreement, there will be a certain diversity of tactical judgments on how to attain generally shared aims, reflected in media debate. But views that challenge fundamental premises... will be excluded from mass media even when elite controversy over tactics rages fiercely. In other words, Fox News and MSNBC disagree over what to report, but neither is going to report anything that is truly disruptive to the goals of moneyed interests. The text is divided into seven chapters, first establishing the model and then going through a series of case studies before concluding. We'll begin with Chapter 1, which details the model and which I'll provide a brief summation of. In following posts (assuming this thread doesn't transform into a pumpkin at 12:01 AM on the 27th) I will go through the case studies and conclusions drawn by the text. And as a brief note: the original text was written in 1988 and updated in 2002. Most of the examples provided by the authors are from the 1980s, and in the introduction to the updated version they are dismissive of the impact of the fledgling internet (which was then and still is now largely dominated by corporate interests) and obviously have no inkling of social media as a political force. I am not asserting that the text is no longer relevant due to these factors, or that the media has somehow transformed into something which this model can no longer address, but wanted to set the context. -------------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 1: A Propaganda Model Chapter 1 introduces the model that will be used for the analysis in the following chapters. The argument is that the media, as a body that simultaneously seeks to inform and entertain, is subject to several filters that any information must pass through before it becomes newsworthy and becomes reported. The filters are as follows: quote:

I am going to, briefly, explain each of these. These guys go on for pages and if you wanted to read all of it you'd get the book. If you think I'm oversimplifying let me know and I'll try to be more detailed in future updates. Size, Ownership, and Profit Orientation: large media outlets are often owned by large corporate entities, and these entities have Making Money as their primary goal. These entities also have interests in many industries and often operate on a global scale, and may have ties to other large powerful interests such as banking or government. Due to these ties and the drive to maintain a profitable enterprise, news that is inconvenient to the goals of making money or that may be damaging to certain industries will be necessarily filtered out or viewed as lacking newsworthiness. The Advertising License to Do Business: media is expensive to run and receives large amounts of its funding via advertising, and advertisers, themselves being corporate interests that are seeking customers to purchase their goods and services, are not interested in advertising along media that is critical of their wares. So media that is critical of, say, labor practices will quickly find itself starved of financial resources due to an inability to find advertisers. Sourcing Mass-Media News: mass media is a large bureaucracy, and the needs of a bureaucracy can only truly be met by another bureaucracy. Enter the government and its many branches, each of which is more than happy to serve up news on a platter for easy distribution with little cost to the money-conscious media enterprise. Further, the media has an interest in simply reporting the government's statements as fact. The presumption of expertise is provided to the government source out of necessity: news needs to be provided daily and at a profit, and in order to ease this process government-provided news is simply restated in the media without critical analysis or significant, if any, verification. And to maintain access to this easy news source, tough questions aren't asked; the threat of losing access is a powerful motivator for media to avoid probing too deeply into the information being provided. The text also goes into great detail about the public relations resources available to entities like the Air Force versus independent activist groups and how the former completely dwarfs the latter (and if you think you've never been at the receiving end of military PR, then I guess you're not a fan of Stargate). Flak and the Enforcers: simply put, news that pisses anyone off will encourage "flak," meaning complaint. Complaint can be organic or organized, but either way is expensive to address, upsets advertisers, and can hurt future profitability, so reported news will always seek to avoid rocking the boat. The powerful have the ability to produce greater flak, which can be direct, such as a call to the editor from someone of significance, or the threat of legislation, or even just demanding a response or apology. This flak can also be indirect, via complaints to their constituencies about the media, or funding think-tanks/advertising that is targeted at damaging the media. In any event, avoiding this ire leads media to self-censor it's reporting. Anticommunism as a Control Mechanism: it is very very VERY important to not seem to be a Red. Anticommunism is used by capital to mark anyone who may stand as a threat to property interests as an enemy and to help mobilize the people against that enemy. And it serves as a helpful tool for splitting those on the left of the political spectrum, many of whom will fight viciously against any appearance that they'd rather be Red than Dead. Per the text: quote:Liberals at home, often accused of being pro-Communist or insufficiently anti-Communist, are kept continuously on the defensive in a cultural milieu in which anticommunism is the dominant religion At first blush this might feel like some Cold War holdover that we've grown past, but replace the word "communist" with "socialist" and it becomes very relevant very quickly. For example, this tweet: https://twitter.com/CharlotteAlter/status/1320091067803422720?s=20 So still very valid. Ultimately, this anticommunism is convenient for the powerful for creating two sides: "our side" and "their side." And the media, interested in staying in the good graces of the powerful, will uncritically report news that is favorable to "our side," meaning the side opposed to communism or socialism or whatever the popular boogeyman word is. In summation: these five filters form the propaganda model and serve to limit what gets reported and who does the reporting. And it's generally self-perpetuating: function well within this allowed range of reporting and you're more likely to get promoted by the owners, and then you're likely to go on and hire more journalists who report that same way because that's the model of reporting you recognize as being good journalism. ----------------------------------------------------- Apologies if I oversimplified or mischaracterized anything, it's somewhat dense. Let me know if you see any problems. In the next few days I will discuss Chapter 2, which details how the media determines the worthiness of victims. Meaning who abroad has suffered deservedly, and who is the victim of unjust excesses. Spoiler alert: the people being hurt by us had it coming. Sorry if I ruined it for you!

|

|

|

|

Life gets in the way, but the first two sections here are alone 866 words. I've completed a partial review of chapters 3 and 4 as well, at the bottom of this post.Robot Jones posted:The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made It Robot Jones posted:The American Tradition: And the Men Who Made It The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made it We are all republicans Chapters 3 & 4 Hofstadter moves from the founding fathers towards two the early-mid 19th century’s most prominent politicians: Andrew Jackson and John Calhoun. Jackson saw the national bank as a tool to shift power from the small farmer to the Northern industrialists. His effort to cripple the bank worked well to shift the balance of power back towards farmers, but caused inflation and credit problems that ended up hurting the farmers far more that the state of affairs under the national bank. Again, Jackson saw the political landscape in terms of the property rights and competing interests of the landed urban and rural classes. Hofstadter further argues that the concept of “Jacksonian Democracy” had little to do with Jackson’s political views. Regrettably I never had the time to finish my thorough review of the "Calhoun" chapter. In short, however, Hofstadter identifies Calhoun as a constitutionalist who saw beyond the sectional struggles of the early-to-mid 18th century to the common class-struggle roots of both the laborer-manufacturer divide in the north and the institution of slavery in the south. His failure to "appreciate the staying power of Capitalism" led his ideas to fail at propping up the slavery-backed plantation system of the south in the face of opposition from the North's capitalist class. From these first four chapters I conclude that Hofstadter was a proponent of the Marxist belief that "the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles." He very convincingly argues that all four of these pivotal figures in American history saw the political landscapes of their times as dominated by the struggle of the capitalist class to maintain power over the others. I give this book 5 out of 5 dollars.

|

|

|

|

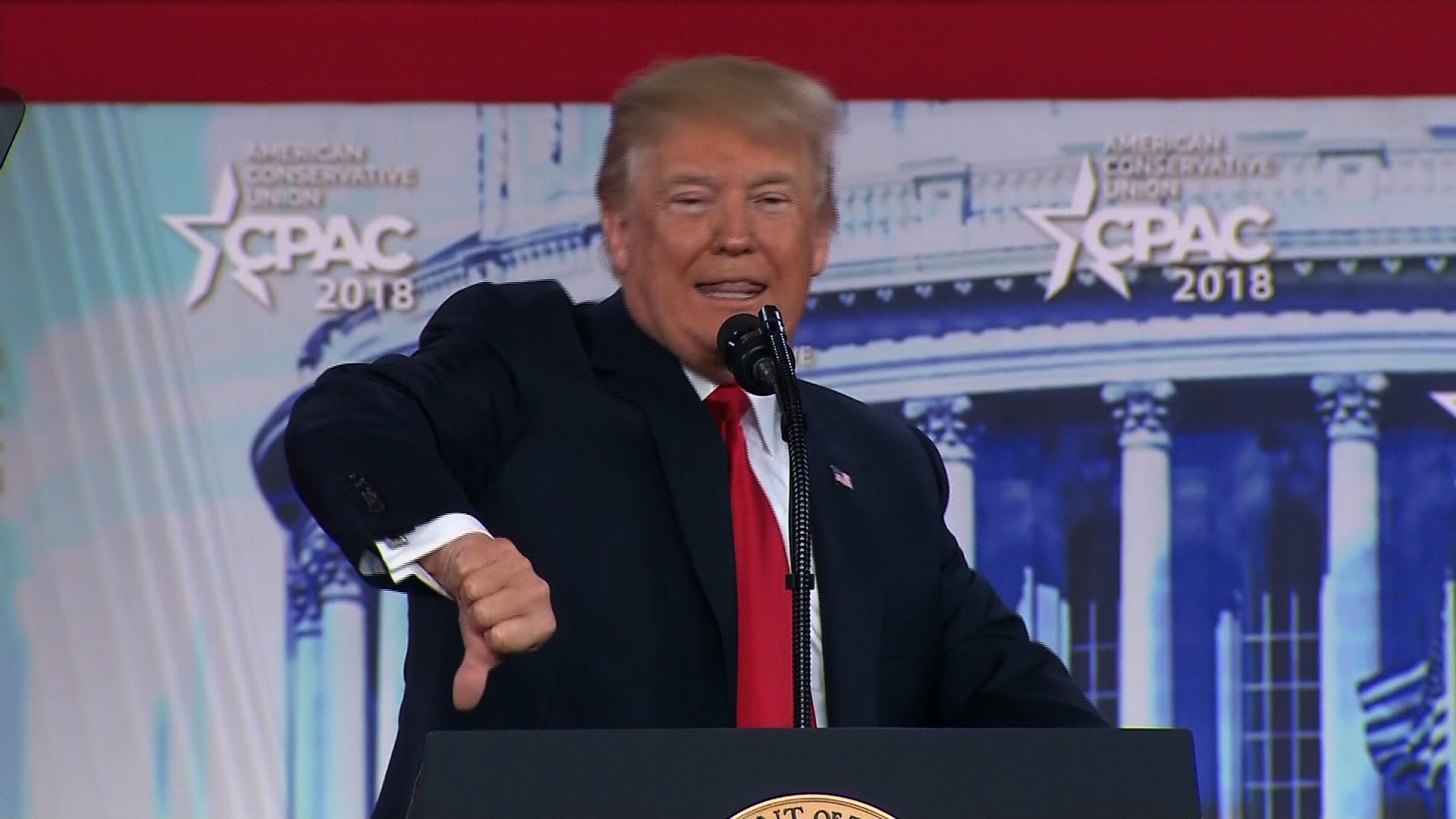

The Concept of the Political by Carl Schmitt Context I got the absolute short end of the stick here. Schmitt was born in 1888, in Westphalia. He is a prominent conservative political theorist. You may be able to connect that date, that location, and that ideology.  Pictured: Schmitt, on the right(lol) Yep. Schmitt was an enthusiastic, active participant in the Nazi party, writing in its favor and attempting to develop its thought until the end of World War II. He’s more than that though. The Concept of the Political is an articulation of political theory fundamentally opposed to peace, democracy, human rights, multiculturalism, and liberalism...and it’s published in 1932. That’s before Hitler came to power. Schmitt isn’t merely a Nazi developing propaganda or an academic hanger-on trying to fit into the party, but a, arguably the, enthusiastic academic trying to justify the mature form of fascism before and during its rise (he was also, of course, a rabid anti-Semite). There is perhaps no more direct, clear or enthusiastic merger between the laughable body of pseudointellectual pap smears called “conservatism” and fascism than this. It’s really, really horrible stuff. I was not surprised to learn that Seven Hundred Bee was so enthusiastic about it. A note about the book’s length: like many profoundly influential quasi-intellectual works, it’s a gross embarrassment to the name “book”. The Concept of the Political is a ~80 page essay written on very small pages. I’m reading the “expanded edition” of the book, a later edit by Schmitt with commentaries and introductions by people I will politely refer to as not fascists per se, but remarkably excited to talk about fascism. I’ll spend a little bit of time with these commentators as appropriate. Foreword by Tracy B. Strong – the dimensions of the new debate around Carl Schmitt Strong is a retired, prominent Nietzsche scholar. After describing Schmitt’s life and how there has been renewed interest in Schmitt, Strong justifies close study of Schmitt’s work. quote:If a definition of an important thinker is to have a manifold of supporters and detractors, the scholars I have cited clearly show Schmitt a thinker to be taken seriously. I want to ask you how comfortable you are with this reasoning. Of course, Strong himself is a Schmitt fan, and thinks that Schmitt’s controversial background is an unfair smear that conflates his belief with his endorsement of Naziism (spoiler alert: Naziism’s all he has). Near the end of the foreword, Strong summarizes his relation to Schmitt’s ideas in the following way: Tracy Strong posted:There is also another reason, this one more generational. An intellectual consequence of the experience with Nazism was to effectively shrink, perhaps one might say homogenize, the language and terms of political debate in the subsequent period. As the Nazi experience fades from consciousness (at just over sixty years of age, I am among the last to have been born during the war and to have been taught by those with adult consciousness during the war), so also possibilities excluded by the specter of Auschwitz have returned. The revival of interest in Schmitt is consequent, I believe, to this increasing distance from the 1930s. How we manage the intellectual terrain that we are opening up is our responsibility. There’s an introduction by George Schwab, the translator, but it’s mostly a fawning summary of the sincerity of Schmitt’s beliefs (Schwab has absolutely riddled the text with footnote interpretations of Schmitt’s meaning). Schwab demonstrates with contextual citations that Schmitt is directly motivated by the fall of the Weimar Republic and that this is the basis of his beliefs- and that in the Concept of the Politicial, “he raises the discussion to a level which transcends Weimar Germany in both space and time.” This is despite the fact that two loving pages later, Schwab notes that Schmitt refuses to consistently define the concept of “the political”. In trying to rehabilitate Schmitt, Schwab is explicit that Schmitt sought to strengthen the Weimar Republic’s structure against political subversion from within…and then remains completely silent on the fact that he was a willing booster for the Nazis in general once the republic failed. Discendo Vox fucked around with this message at 02:58 on Oct 27, 2020 |

|

|

|

Seven Hundred Bee posted:First off, thank you to everyone who's been posting updates! Great job to all. To our other participants, you have until October 26th! You should seriously consider making this mixed media criticism. There's a whole world of kirk cameron out there waiting.

|

|

|

|

goathe.cx has FAILED the book review challenge and been righteously punished.

|

|

|

|

He should have done the old send-an-email-saying-the-review-is-attached-but-without-an-attachment gambit—might have bought a few hours.

|

|

|

|

Discendo Vox posted:Near the end of the foreword, Strong summarizes his relation to Schmitt’s ideas in the following way:

|

|

|

|

So, why did I assign a book by Carl Schmitt, a literal Nazi jurist whose entire philosophy was "strong man good"? Because, sadly, his work is becoming increasingly popular in China: quote:For the past several years, the study of German jurist Carl Schmitt has exploded in China. Floria Sapio remarks that Schmitt has enjoyed “enormous currency among mainland Chinese scholars since the 2000s.”1 Even though Schmitt has received a recent revitalization of interest of his thought among Western scholars,2 he is still known primarily for his aphoristic (and largely untranslated) texts on political theory and his infamous association with the Nazi Party. Yet, the reason that this esoteric and controversial thinker has garnered any consideration within Chinese academia is no mystery: Carl Schmitt was a political philosopher of illiberalism. He believed that liberalism had “a tendency to undermine a community's political existence” because a state founded on such an ideology “will lack the power to protect [citizens] from external enemies.”3 http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1784/totalitarian-friendship-carl-schmitt-in-contemporary-china As China under Xi is looking for an alternative political framework than Marxism, they've looked towards Schmitt's strong-man-centered rejection of liberalism.

|

|

|

|

Seven Hundred Bee posted:So, why did I assign a book by Carl Schmitt, a literal Nazi jurist whose entire philosophy was "strong man good"? Of all the ambitions and projects that china has been building up to over the last few decades, cultural homogeneity is the most insane one to me. The sheer size and density of the country makes it seem like a doomed effort from the get-go, but boy howdy are they taking a real solid crack at it. I was not particularly familiar with Schmidt, but from Discendo Vox's review, it sure sounds like a very natural fit for that specific ambition. From what I gather, the trend towards homogeneity started long before this newfound interest, so I don't think sadly is quite the right framing here. I would expect that all Schmidt brings to the table is just post-hoc validation of a project that has been long in the making, not the foundations for one like what happened in Germany. Aramis fucked around with this message at 17:17 on Oct 27, 2020 |

|

|

|

To be clear I'm just getting started; the review directly explaining Schmitt's framework as written and how garbage it is will be along soon.

|

|

|

|

I've been curious what's the deal with Schmitt since edgelords got into him the last few years, really looking forward to it.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 9, 2024 09:43 |

|

Peel posted:I've been curious what's the deal with Schmitt since edgelords got into him the last few years, really looking forward to it. I am at this point going to need a few days to be in a place where I am able to finish writing this up.

|

|

|