|

Easter and Work kind of bit into my ability to post, so two chapters today! Chapter 9: The Banner quote:LIGHT SNOW FELL BEFORE before the companions had journeyed a day from King Smoit's castle, and by the time they reached the Valley of Ystrad the slopes were whitecloaked and ice had begun to sheathe the river. They forded while frozen splinters cut at the legs of their horses, and wended through the bleak Hill Cantrevs, pressing eastward toward the Free Commots. Of all the band, Gurgi suffered most grievously from the cold. Though bundled in a huge garment of sheepskin, the unhappy creature shivered wretchedly. His lips were blue, his teeth chattered, and ice droplets clung to his matted hair. Nevertheless, he kept pace at Taran's side and his numbed hands did not loosen their grip on the banner. Days of harsh travel brought them across Small Avren to Cenarth, where Taran had chosen to begin the rallying of the Commot Folk. But even as he rode into the cluster of thatch-roofed cottages, he saw the village thronged with men; and among them Hevydd the Smith, barrel-chested and bristle-bearded, who shouldered his way through the crowd and clapped Taran on the back with a hand that weighed as much as one of his own hammers. The commot-folk are good people, but we already knew that. quote:Heartened by the Weaver-Woman's promise, the companions departed from Gwenith. A short distance from the Commot, Taran caught sight of a small band of horsemen riding toward him at a quick pace. Leading them was a tall youth who shouted Taran's name and raised a hand in greeting. With a glad cry Taran urged Melynlas to meet the riders. Coll's pretty strategic for a grower of turnips. quote:Quickly they set their plans. Taran rode ahead, calling to the horsemen and foot soldiers, who hastily caught up their weapons and followed after him. He ordered Eilonwy and Gurgi to safety among the carts; without waiting to hear their protests, He galloped toward the fir forest covering the outlying hills. The marauders were armed more heavily than Taran had expected. Swiftly they sped down from the snow-covered ridge. At a sign from Taran, the bowmen raced and flung themselves into a shallow gully, and the mounted warriors of the Commots wheeled to the charge. The riders met in a turmoil of hoofs and clash of blades. Then Taran raised his horn to his lips. At the piercing, echoing signal, the bowmen rose from cover. RIP, Annlaw Clay-Shaper. quote:BY MIDWINTER, the last of the war bands had been gathered and the Commot warriors dispatched to Caer Dathyl. In addition to a troop of horsemen, Llassar, Hevydd, and Llonio still remained with Taran, who now led the companions northwestward through the Llawgadarn Mountains. I love this chapter. It's both heart-warming and -breaking. Chapter 10: The Coming of Pryderi quote:CAER DATHYL WAS an armed camp, where sparks like blazing snowflakes whirled from the armorers' forges. Its widespreading courtyards rang with the iron-shod hooves of war horses and the sharp notes of signal horns. Although the companions were now safe within its walls, the Princess Eilonwy declined to exchange her warrior's rough garb for more befitting attire. The most she agreed to do--- and that reluctantly--- was to wash her hair. A few ladies of the court remained, the rest having been sent to the protection of the eastern strongholds, but Eilonwy flatly refused to join them in their spinning and weaving chambers. When he was a giant, he never had blisters on his hands. quote:MORE THAN A STRONGHOLD of war, Caer Dathyl was a place of memory and a place of beauty. Within its bastions, in the farther reaches of one of its many courtyards, grew a living glade of tall hemlocks, and among them rose mounds of honor to ancient kings and heroes. Halls of carved and ornamented timbers held panoplies of weapons of long and noble lineage, and banners whoseemblems were famed in the songs of the bards. In other buildings were stored treasures of craftsmanship sent from every cantrev and Commot in Prydain; there, Taran saw, with a twinge of heart, a beautifully fashioned wine jar from the hands of Annlaw Clay-Shaper. The companions, when spared from their tasks, found much of wonder and delight. Coll had never before journeyed to Caer Dathyl, and he could not help staring at the archways and towers that seemed to soar higher than the snow-capped mountains beyond the walls. Good lesson from Taliesin there. quote:Taran was about to speak, but the notes of a signal horn rang from the Middle Tower and shouts rose from the guardians at the turrets. Watchers cried out the sighting of King Pryderi's battle host.Taliesin led the companions up a broad flight of stone steps where, from atop the Hall of Lore, they could see beyond the walls of the fortress. Taran could only glimpse the gleam of the westering sun on ranks of spears across the valley. Then, mounted figures broke away from the mass and galloped across the snow-flecked expanse. Against the rolling meadow, the leading rider of the band was sharply brilliant in trappings of crimson, black, and gold, and sunlight sparkled on his golden helmet. Taran could watch no longer, for guards were shouting the names of the companions, summoning them to the Great Hall. Catching up the banner of the White Pig, Gurgi hastened after Taran. The companions quickly made their way to the Great Hall. A long table had been placed there and at its head sat Math and Gwydion. Taliesin took his seat at Gwydion's left hand; to the right of Math stood an empty throne draped in the colors of King Pryderi's Royal House. On either side sat the Lords of Don, cantrev nobles, and war leaders. Starting to think this Pryderi might be a bad guy, y'all.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 27, 2024 08:36 |

Wahad posted:

Tactical Turnip Troops. E: These chapters are so good, with the building up of Pryderi as the solution and his sudden reveal as a proud rear end in a top hat. All the while seeing Taran keep growing.

|

|

|

|

|

Taliesin is well-written (like all the characters), but in retrospect, it’s kind of odd that he’s so low-key, considering his… panache, for want of a better term, in virtually every legend in which he appears.

|

|

|

|

This book does an amazing job of just feeling like an ending at every turn. The events really do feel like they're moving towards a climax after which Things Will Be Changed.

|

|

|

|

What a Prydick!

|

|

|

|

Strategic Tea posted:What a Prydick! LOL Beefeater1980 posted:Tactical Turnip Troops. I feel like we have been here before with Morgant in The Black Cauldron. Definitely a common message that pride and strength in war are a dangerous combination. I'd be very interested to look up the author's biography and see what he was up to during WW2. Coca Koala posted:This book does an amazing job of just feeling like an ending at every turn. The events really do feel like they're moving towards a climax after which Things Will Be Changed. I completely agree with this. It is a wonderful capstone to the more YA books that build up to it.

|

|

|

|

Chapter 11: The Fortressquote:FOR AN INSTANT, none could speak. The silver bells at the legs of Pryderi's hawks tinkled faintly. Then Taran was on his feet, sword in hand. The cantrev lords shouted in rage and drew their weapons. Gwydion's voice rang out, commanding them to silence. Pryderi did not move. His retainers had unsheathed their blades and formed a circle about him. The High King had risen from his throne. And so Pryderi goes, and it is battle, then, in the Golden Fortress of the Sons of Don. quote:GWYDION HAD EXPECTED the army of King Pryderi to attack at first light, and the men in the fortress had labored through the night making ready to withstand a siege. When dawn came, however, and the pale sun rose higher, Pryderi's battle host was seen to have advanced but little. From the wall Taran, Fflewddur, and Coll, with the other war leaders, watched beside Gwydion, who stood scanning the valley, and the heights that dipped in raw ridges to the flatlands. Snow had not fallen for some days; gullies and rocky fissures still held streaks and patches of white, caught among the crevices like tufts of wool, but the broad meadowland was, for the most part, clear. The dead turf showed in dark brown splotches under a ragged mantle of frost. Scouts had brought word that Pryderi's warriors , held the valley in strength and barred passage through the battle lines. Nevertheless, no skirmishers or flanking columns of riders had been seen abroad; and the scouts judged, from this and the stationing of the foot soldiers and horsemen, that the attack would come in a great forward thrust, as an iron fist against the gates of Caer Dathyl. Now all is done that men can do, and all is done in vain.

|

|

|

|

quote:"To me, Arawn can promise nothing I do not already have," answered Pryderi. "But Arawn will do what the Sons of Don failed to do: Make an end of endless wars among the cantrevs, and bring peace where there was none before." gently caress, I really wish this weren't so goddamn topical.

|

|

|

|

Wahad posted:Chapter 11: The Fortress I like how the battle is written as complete chaos, and Eilonwy finally gets to be in some fighting. Taran and all the others are fairly sexist/patronising to her (yes, I know it’s these are 60 year old books)

|

|

|

|

Hemp Knight posted:I like how the battle is written as complete chaos, and Eilonwy finally gets to be in some fighting. Taran and all the others are fairly sexist/patronising to her (yes, I know it’s these are 60 year old books) In fairness, I don't think its written in a way that makes Taran look good for being so, or Eilonwy bad for fighting. If anything, she comes off as being correct in her choices and Taran as being sexist.

|

|

|

|

I'd agree, it's depicting but not endorsing such.

|

|

|

|

|

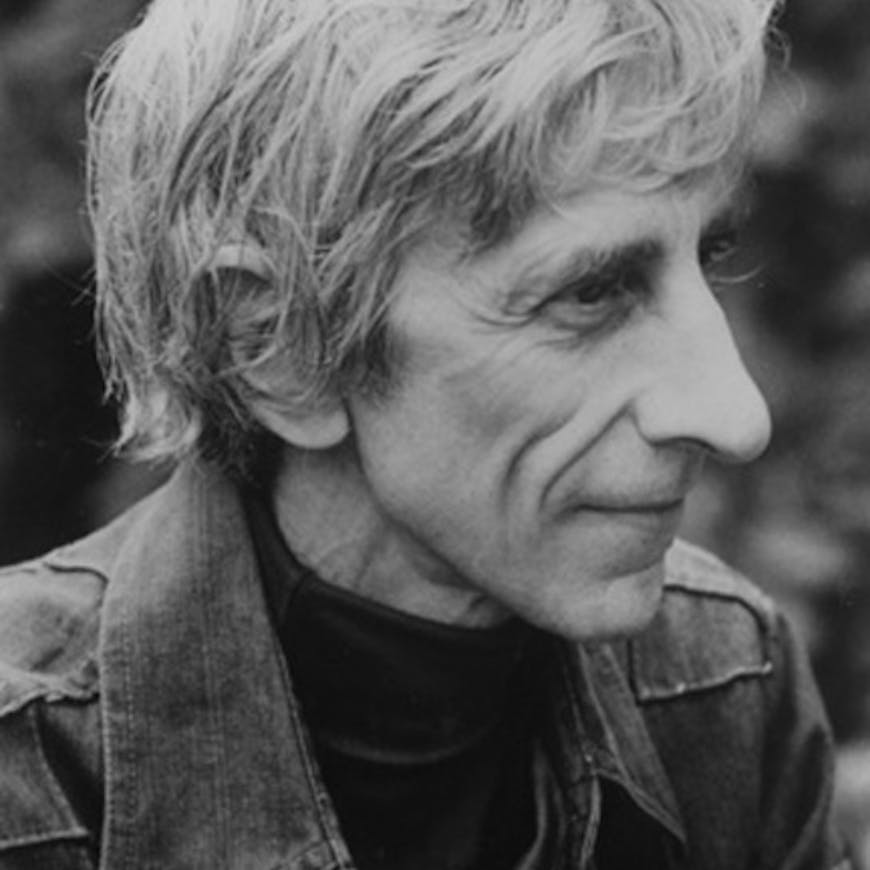

Here's an author bio of Lloyd Alexander from the first edition of Cricket Magazine in 1973. He was a major contributor to the early era of the magazine and was on its board of editors, so Prydain-related stuff crops up in the early volumes fairly frequently.

|

|

|

|

All this week I’ve been wishing there was a complete online archive of Cricket Magazine. My sister passed down her copies from when the magazine would pick one color to use with the otherwise monochrome illustrations, and I remember there being some fantastic stories in those issues.

|

|

|

|

Darthemed posted:All this week I’ve been wishing there was a complete online archive of Cricket Magazine. My sister passed down her copies from when the magazine would pick one color to use with the otherwise monochrome illustrations, and I remember there being some fantastic stories in those issues. I do too! I have an almost-complete physical collection, but only up through the mid 2000s or so. I'll post some of the Prydain-related ephemera as I come across it.

|

|

|

|

Ravenfood posted:In fairness, I don't think its written in a way that makes Taran look good for being so, or Eilonwy bad for fighting. If anything, she comes off as being correct in her choices and Taran as being sexist. Honestly, “Eilonwy is right, Taran is wrong” is a running theme in the series really.

|

|

|

|

Owl at Home posted:Here's an author bio of Lloyd Alexander from the first edition of Cricket Magazine in 1973. He was a major contributor to the early era of the magazine and was on its board of editors, so Prydain-related stuff crops up in the early volumes fairly frequently. That's a beautifully Renaissance face. You can see it in the background of a hundred late 15th century Italian paintings.

|

|

|

|

Honestly, other than the hairstyle, could be ancient Roman.

|

|

|

|

|

Dude had an incredible face. You can definitely see how Fflewddur Fflam was his self-insert character based on how he's described in the books

|

|

|

|

silvergoose posted:Honestly, other than the hairstyle, could be ancient Roman. The little flick of hair is specifically how the first emperor Augustus appeared in all of his official portraits, it's like his trademark

|

|

|

|

I just wanted to echo the rest of the thread, and thank you for posting these. I devoured these books as a kid, and it's been an absolute joy realizing that they're even better than I remembered. Owl at Home posted:Here's an author bio of Lloyd Alexander from the first edition of Cricket Magazine in 1973. He was a major contributor to the early era of the magazine and was on its board of editors, so Prydain-related stuff crops up in the early volumes fairly frequently. This is great, thanks. I was going to ask this after the books were finished (and probably still should), but does anyone have any recommendations for Alexander's other work?

|

|

|

|

filmcynic posted:I just wanted to echo the rest of the thread, and thank you for posting these. I devoured these books as a kid, and it's been an absolute joy realizing that they're even better than I remembered. https://youtu.be/Wt9ZHQy2wAk?si=YhvIxjTEVBSucL5N Everything on the channel is amazing.

|

|

|

|

Owl at Home posted:

Yeah, I think Disney definitely based their take on Fflewddur off of Alexander.

|

|

|

|

filmcynic posted:This is great, thanks. I was going to ask this after the books were finished (and probably still should), but does anyone have any recommendations for Alexander's other work?

|

|

|

|

Missed another few days. Still wrangling a mad busy work schedule, sorry folks. Still, only one chapter this week, because it's an important one. Chapter 12: The Red Fallows quote:ALL NIGHT THE DESTRUCTION raged and by morning Caer Dathyl lay in ruins. Fires smouldered where once had stood the lofty halls. The swords and axes of the Cauldron-Born had leveled the hemlock grove near the mounds of honor. In the dawn light the shattered walls seemed bloodstained. The army of Pryderi, denying even the right of burial for the slain, had driven the defenders into the hills east of Caer Dathyl. And so the stakes are raised again. Victory in this, or all will be lost. quote:LLASSAR, HEVYDD, AND ALL the other Commot folk chose to follow Taran. With them were joined the surviving warriors of Fflewddur Fflam, and together they made the greater portion of Taran's band. To the surprise of the companions, Glew chose to ride with them. The former giant had recovered from his fright, at least enough to regain much of his customary peevishness. He had, however, regained all of his appetite and demanded food in great quantity from Gurgi's wallet of provisions. The fight is lost, but the war is not yet over. Onwards! quote:IT WAS COLL'S JUDGMENT that the Cauldron-Born would march directly to Annuvin, following the straightest and shortest path. At the head of the column winding its way from the snowswept heights, Llassar rode beside Taran. The skill of the young shepherd eased their passage, and he guided them swiftly toward the lowlands, unseen by Pryderi's army which had begun to withdraw from the valley around Caer Dathyl. For some days they journeyed, and Taran began to fear the retreating Cauldron-Born had outdistanced them. Nevertheless, they could do no more than press on as quickly as possible, southward now, passing through long stretches of sparse woodland. Rest in peace, Coll Son of Collfrewr. quote:WHILE THE GRIEVING COMPANIONS gathered stones from the ruined wall, with his own hands Taran hollowed out a grave in the harsh earth, allowing none other to aid him in this task. Even when the humble mound had risen above Coll Son of Collfrewr, he did not move from it, but ordered Fflewddur and the companions to press on into the Hills of Bran-Galedd, where he would join them before nightfall.For long he stood silently. As the sky darkened, at last he turned away and climbed heavily astride Melynlas. He halted another moment by the mound of red earth and rough stones. The description of the Red Fallows, and the death of Coll, is the part I remember most about this book, even all this years later. So I thought it best to present this chapter by itself.

|

|

|

|

God, I thought Coll's death and the fall of Caer Dathyl were spaced a little farther apart, but then I remember that these books are like under 200 pages, so poo poo moves real fast in them. to a real one though. Coll's death was the one death in the books that legitimately upset me, which was entirely the point of it. to a real one though. Coll's death was the one death in the books that legitimately upset me, which was entirely the point of it.

|

|

|

|

filmcynic posted:I just wanted to echo the rest of the thread, and thank you for posting these. I devoured these books as a kid, and it's been an absolute joy realizing that they're even better than I remembered. There was one which was about a fictionalised version of the Tang dynasty I think? A boy emperor gets deposed and goes on a sort of odyssey across his kingdom. The Journey of prince Jen or Yen or something?

|

|

|

|

Wahad posted:Chapter 12: The Red Fallows This line is one of the ones that really speaks to how far Taran has come from where he was in the first book. Taran of the Book of Three wanted exactly what Taran of the High King has.

|

|

|

|

I dunno. Trying to slow down an army of undead by defending one wall and they just walk around it and then spending an hour in digging a grave does not seem an optimal military solution. I’m not sure why the undead decided to go into the mountains either so perhaps both sides are a bit brain dead.

|

|

|

|

Wahad posted:Missed another few days. Still wrangling a mad busy work schedule, sorry folks. Still, only one chapter this week, because it's an important one. Coll was one of the 2 losses in this book that hit me the hardest. I thought he died in the battle at Caer Dathyl though, and not a little after it though.

|

|

|

|

Comstar posted:I dunno. Trying to slow down an army of undead by defending one wall and they just walk around it and then spending an hour in digging a grave does not seem an optimal military solution. Their military efforts convinced young me given the suspension of disbelief. But yeah as an adult I think they'd all just get massacred. But maybe that's because I'm imagining the cauldron-born as tireless zombies? Which would obviously just exhaust all the defenders in an hour or two, then slaughter them. But it is sort of implied that they are tiring in some slightly inhuman way, they can't simply keep trying to get over the wall until they succeed.

|

|

|

|

The thing with the Cauldron-born has always been that they cannot venture too far from Annuvin (stated way back in book 1 and 2!). Something about the Cauldron's curse wanes when they are further from Arawn's power, and, presumably, if they stayed away too long, they'd just...fall over? That part's unclear. But yeah, that's why Taran's goal here is explicitly "delay the cauldron-born" and not "prevent them from returning entirely." The first part is doable. The second part not so much.

|

|

|

|

Chapter 13: Darknessquote:IN THE DAYS THAT FOLLOWED, the companions strove to overtake the Cauldron-Born and again fling themselves across the path of the retreating warriors, but their progress was agonizingly slow. Taran knew Coll had spoken truly when he had called the Hills of Bran-Galedd both friend and foe: the rocky troughs and narrow defiles, the sudden drops where the ground fell away sharply into frozen gorges offered the companions their only hope of delaying the deathless host moving onward like a river of iron. But at the same time, from the high crags of the west, gusts of snow-laden wind battered the struggling band with icy hammers. The winding trails were slippery and treacherous. The ravines held deep pits filled with snow, where horse and rider might founder beyond rescue. In the hills, Taran's most trusted guide was Llassar. Surefooted, long used to mountain ways, the Commot youth was now shepherd to a different, grimmer flock. More than once, Llassar's keen senses kept the companions from the icy traps of snow-hidden crevices, and he discovered pathways no other eye could see. But the progress of the ragged band was nonetheless slow, and all suffered cruelly from the cold, men and animals alike. Only the great cat, Llyan, showed no concern for the bitter blasts that drove frosty needles against the faces of the companions. Uh oh. quote:Fearful and dismayed, Taran and Fflewddur pressed their way through the shattered remnants of the war band struggling to regain their ranks. Torches had been lit to signal rallying points for the stragglers, who stumbled wounded and bewildered among the bodies of their fallen comrades. Throughout the night Taran searched frantically, sounding his horn and shouting the names of the lost companions. With Fflewddur, he had ridden beyond the battleground, hoping for some sign of either one of them. There was none, and the new snowfall, which began toward dawn, covered all, tracks. By midmorning, the survivors had gathered. Good ol' Doli! quote:For the first time since leaving Caer Dallben, Glew appeared in good spirits. The idea of anything resembling a cavern seemed to cheer him, although the result of his improved temper was a further spate of rambling tales about his own feats as a giant. However, after a hard day and night of marching, when Doli halted at the sheer face of a high cliff, the former giant began glancing about fearfully. His nose twitched and his eyes blinked in dismay. The entrance to the ancient mine toward which the dwarf beckoned was no more than a fissure in the rock, barely wide enough for the horses, overhung with icicles glistening like sharp teeth. Who's idea was it to take Glew along, again?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 27, 2024 08:36 |

|

Wahad posted:Chapter 13: Darkness FIRST OF ALL i think you mean King Glew and second of all if he had been restored to his giant form AS REQUESTED MANY TIMES then he never would have even fit in the tunnel in the first place and would not have been able to destroy it so really who is at fault here

|

|

|