|

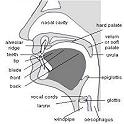

FoiledAgain posted:This is not a useful test for distinguishing parts of speech. There is nothing obviously wrong with (c), despite the noun being cut-out. If the lead-up sentence had been "We purchased some peyote.", then (c) means nothing very different. I hear what you're saying about the test; the test I proposed obviously only works if the sentence is taken in isolation, just as your test case #2 only works if we isolate your adjectives ("a silly boy" is perfectly fine). I chose my test over others because the question on the table was whether "a lot" was generally used as a verb or a noun. It was, in other words, a parts of speech question. I agree that "a lot" is a quantifier, but a quantifier is not a part of speech for the same reasons homo sapiens is not a phylum or a tire is not a car. Parts of speech questions only have eight possible answers: verb, noun, pronoun, adjective, adverb, proposition, conjunction, or interjection. Quantifiers, like articles, are adjectives.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 10, 2024 00:04 |

|

Technically, "a lot" is a noun which then takes "of" in a partitive sense. It's a quantity rather than a quantifier.

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:2) Noun phrases can take determiners, adjectives do not. What about substantives? "Bring me your tired, your hungry, your poor..." Bel_Canto posted:Technically, "a lot" is a noun which then takes "of" in a partitive sense. It's a quantity rather than a quantifier. Also this ^^^^^. But bear in mind that it CAN also be an adverb, "We go to the movies a lot." Should there be a breakaway grammar a/t thread?

|

|

|

|

exactduckwoman posted:Should there be a breakaway grammar a/t thread?

|

|

|

|

Bel_Canto posted:Technically, "a lot" is a noun which then takes "of" in a partitive sense. It's a quantity rather than a quantifier. This usage is in circulation. However, common usage is as an adjective, as in "I feel a lot of [much] pain," or occasionally as an adverb, as in "I run a lot [much]." English has nothing like the Académie française, so usage is where we con meaning; that's why the OED tracks usage over time and defines words inductively. And usage suggests that "a lot" has a meaning as a modifier that is distinct from its meaning as a noun. Brainworm fucked around with this message at 23:10 on Jun 1, 2009 |

|

|

|

exactduckwoman posted:Should there be a breakaway grammar a/t thread? I think it would just end up looking like Thunderdome with lower stakes.

|

|

|

|

Brainworm posted:I hear what you're saying about the test; the test I proposed obviously only works if the sentence is taken in isolation, just as your test case #2 only works if we isolate your adjectives ("a silly boy" is perfectly fine). I said that "noun phrases" can have determiners - silly boy is a noun phrase, which contains an adjective. I would like to think that my example works better, at least with native speakers. English speakers will react more strongly to the ungrammatical *the silly than they will to the perfectly grammatical example you gave in (c). quote:Quantifiers, like articles, are adjectives. No. Articles are not adjectives. This wikipedia page has a short list of crucial grammatical differences. I know that traditional grammar may treat them as the same thing, but that's wrong. So to avoid turning this into a grammar discussion, let's turn it back to you - as an English prof, how much detail should we skimp over in teaching grammar? What kind of information do you consider "irrelevant" for students? Why should we pretend that quantifiers are adjectives? (That question sound more hostile than I mean it.) exactduckwoman posted:What about substantives? Those are adjectives in a headless noun phrase, meaning that here is a noun phrase in that structure, but the slot for the noun in unoccupied. We could fill that slot: Bring me your tired people, your hungry people, your poor people. As adjectives, we can find a superlative form: Bring me your most tired, your hungriest, and your poorest. As adjectives, they don't pluralize: *Bring me your tireds, your hungrys, and your poors. Note that this is not the same as "the red" in "The red on your walls in lovely". That's a full out noun. *The reddest on your walls is lovely The reds on your walls are lovely. quote:Should there be a breakaway grammar a/t thread? Here.

|

|

|

|

English majors etc really should at least take the intro linguistics courses at their respective institutions of higher learning! (I've said this before and more people need to say it)

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:No. Articles are not adjectives. This wikipedia page has a short list of crucial grammatical differences. I know that traditional grammar may treat them as the same thing, but that's wrong. And this is why Wikipedia is a lousy source. Not because anything it says about determiners is necessarily wrong, but because it ignores the the ways traditional grammar is taught: eight classes of words that are divided and subdivided into sub- and sub-subclasses. A good example is here. It's not that traditional grammar treats adjectives and quantifiers and articles as the same thing; it classes all of these as adjectives (in that they modify nouns) and subclasses them (as adjectives proper, articles, etc.) according to how they modify nouns. That may or may not be the system that linguists prefer, but it's the system that I inherit from secondary schools at home and abroad. quote:[H]ow much detail should we skimp over in teaching grammar? What kind of information do you consider "irrelevant" for students? Why should we pretend that quantifiers are adjectives? (That question sound more hostile than I mean it.) It depends on the students. In my line of work, grammar's useful only insofar as it lets students talk about style. There are two reasons for this. The first is that even the most basic writers get most of the grammar that matters essentially correct, and common writing problems (say, comma splices) are easier to approach as matters of style. Having a student read a run-on sentence aloud will almost always prompt its satisfactory repair. The second is that knowledge of formal grammar doesn't improve the grammaticality of student writing. This is counterintuitive, but backed by more research than practically any other point in Rhetoric and Composition studies -- the matter's been studied for more than a century, using bafflingly diverse approaches, and every study gets to the same end. And someone re-studies it every couple years anyway. So if you want to teach writing to native speakers, even basic ones, covering rules of grammar is a waste of time. There is, reliably, exactly zero payoff in terms of increased grammaticality. My job would be much easier if this weren't the case, believe me. It used to be the case that foreign languages were taught structurally, and this is still true in some places. My ESL students especially come in relying on the eight-parts-of-speech hierarchical grammar I just detailed. Knowledge of formal grammar there allegedly makes sense because of grammatical parallels between English and Romance languages. But my understanding is that these methods have fallen out of favor for the same reasons the teaching of formal grammar has fallen out of favor in writing classrooms; it turns out that this structural grammatical knowledge is of demonstrably little use in language acquisition. There's a real payoff to formal grammar in more advanced writing, though. Say we're talking about how a phrase works: quote:Bring me your tired, your hungry, your poor... I disagree* with your reading these adjectives in a headless noun phrase; this phrase is synechdotal,** in that words that are commonly used as adjectives are being pressed into service as nouns (the "part" of the "whole" is in this case situational rather than material). It should be obvious that any discussion of how this synecdoche works requires some formal grammar for a naming of parts. A better example might draw on our "a lot." If this came up in a formal writing class, we'd talk about it as a dead metaphor; the earliest uses for the word were quantities (roughly like "a bunch"), which suggests that its use as a modifier originated in a metaphorical application: "How much pain are you in, Chuck?" "A lot." "I see. You've cleverly described your pain as though it were a collection of like objects in order to emphasize its quantity." "A lot," like "a bunch," is no longer metaphorically evocative, though -- it doesn't ask the reader or listener to imagine that pain has a physical dimension that allows it to be gathered like so much hay. But the really useful thing about dead metaphors is that they make great zombies. You can craft an evocative trope from the "a lot" tradition by choosing some conceptual equivalent that hasn't been drained of its imaginative juices: "How much pain are you in, Chuck?" "How much can you fit in a Winnebago?" "I see. You've cleverly described your pain as though it were a collection of like objects that could be housed only in the largest of automobiles, and so emphasized its quantity." In this case, a nose for grammar helps sniff out the potential in what's otherwise a well-beaten phrase. But in both these advanced cases, you'll notice, the grammaticality of student writing is basically a nonissue. * Wrong word. I don't think your parsing of the phrase is incorrect, only that other parsings are differently useful. ** Also you could read it metonymically. Here, that's not a significant difference -- composition and association pretty much end in teh same place.

|

|

|

|

Brainworm posted:And this is why Wikipedia is a lousy source. Not because anything it says about determiners is necessarily wrong, but because it ignores the the ways traditional grammar is taught: eight classes of words that are divided and subdivided into sub- and sub-subclasses. A good example is here. So Wikipedia is lousy because it disagrees with you? You admit the information is correct, but you would rather ignore it because that's not what you grew up with. If you would prefer a more academic source, I can seek one out for you. quote:The second is that knowledge of formal grammar doesn't improve the grammaticality of student writing. This is counterintuitive, but backed by more research than practically any other point in Rhetoric and Composition studies -- the matter's been studied for more than a century, using bafflingly diverse approaches, and every study gets to the same end. And someone re-studies it every couple years anyway. I can agree that formal knowledge of grammar won't help you write better. You can't write a more compelling story line just because you can identify a relative clause (for instance). I would, however, be interested in any of these studies. I'm a little surprised that grammatical instruction has *no* effect on writing, but since you have frequently confused style and grammar in this thread, maybe I'm just misunderstanding you. quote:I disagree* with your reading these adjectives in a headless noun phrase; this phrase is synechdotal,** in that words that are commonly used as adjectives are being pressed into service as nouns (the "part" of the "whole" is in this case situational rather than material). It is a very simple fact of English grammar that nouns pluralize, and adjectives do not. How can you possibly claim that your poor has a noun, when *your poors is ungrammatical? If that were truly a noun, pluralization would be possible. If you disagree with that, then I guess there is nothing more to talk about. With all due respect, you are wrong. edit: changed my mind about something FoiledAgain fucked around with this message at 03:44 on Jun 2, 2009 |

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:Here. I meant for quick grammar & usage questions, a bit more accessible than that one. Sorry for the derail, Brainworm

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:It is a very simple fact of English grammar that nouns pluralize, and adjectives do not. How can you possibly claim that your poor has a noun, when *your poors is ungrammatical? If that were truly a noun, pluralization would be possible. What about collective plurals? "Sheep"

|

|

|

|

Ah, well if you want to claim that the plural of the noun poor is poor (analogous to sheep) you could do that. But it still wouldn't explain why you can make the comparative and superlative out of poor. Nouns shouldn't be able to do that. Sorry to poo poo up the thread on this point, Brainworm. I'm actually quite interested in most of it. I like reading your posts on how you interpret various works. We just have totally different background in language analysis. As a linguist, I feel compelled to comment on your analyses that I disagree with. quote:I meant for quick grammar & usage questions, a bit more accessible than that one. If you want detailed, factual answer about how grammar works, ask a linguist. Should an answer be unclear or too technical, there are plenty of patient people in that thread who will help you out. If you want style or usage questions, then I agree, that thread will be of no help.

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:So Wikipedia is lousy because it disagrees with you? You admit the information is correct, but you would rather ignore it because that's not what you grew up with. If you would prefer a more academic source, I can seek one out for you. No. Wikipedia is a bad source because there are clearly at least two competing methods for organizing the terminology of English grammar in circulation, and Wikipedia doesn't recognize this. I'm sure we can trade source citations all day, but that's not going to resolve this, and I'm not sure it needs resolving. There is no reason why different fields would not organize English grammar as best fits their disciplinary missions. quote:I can agree that formal knowledge of grammar won't help you write better. You can't write a more compelling story line just because you can identify a relative clause (for instance). I would, however, be interested in any of these studies. I'm a little surprised that grammatical instruction has *no* effect on writing, A good, comprehensive summary article on this research on this is Hartwell's "Grammar, Grammars, and the Teaching of Grammar," which is now about twenty years old but does a good job explaining the late 19th and early-to-mid-20th century research on this. Since then, there've been two really large studies on the topic that I know of; one's headed by David Bartholomae, who presented his rough findings at CCCC (the Conference for College Composition and Communication) a few years ago. They're in line with what you'd expect: pre-and post testing of students' knowledge of grammar rules showed improvement, but the grammaticality of their writing improved slightly less than that of a control group which received no grammar instruction. The second is by a guy named Zaleski, who I consult with at ETS; that's a large study and still in progress, and the preliminaries are interesting because some ESL students seem to show improvement. But it's the usual story for native-language writers. Believe me, everybody's shocked and baffled by this the first time they hear it, because it runs deeply contrary to common sense. And nobody's locked up why things work this way (that matter, rather than getting different results, has been the object of most of these studies for the past few decades). Hartwell has an interesting conjecture, though, that goes something like this: You've got a grammar in your head that you acquire more-or-less whole-language style as a native speaker. This operates according to a this-sounds-right reflexive logic. Learning grammatical rules doesn't change the way the this-sounds-right logic works, and so doesn't hook into the process people use to get words onto the page. It's like quitting smoking, sort of. I can know that smoking's bad for me, but that doesn't change the processes my brain uses to decide whether I smoke -- instead, using my academic knowledge of smoking's effects to influence my smoking decisions requires constant and intensive monitoring of my behavior. That's the grammar problem, sort of. Nobody seems to be able to figure out exactly what the writing/grammar equivalent of that constant and attentive monitoring looks like. The closest parallel seems to be proofreading, and there's no evidence that works better with formal grammatical instruction. This doesn't mean that student writing never becomes more grammatical. Obviously it does. But the process by which this happens seems to be unaffected by learning formal grammatical rules. So again and again and again you see something that looks like Bartholomae's results. Some methods of teaching formal grammar are used in experimental classes, while no discussion of formal grammar is used in a control class. The students who receive grammatical instruction improve their knowledge of formal grammatical rules, and the control class does not. The grammaticality of all the groups' writing shows roughly similar improvement, except occasionally when the grammar-instructed students lag slightly behind (probably because grammar instruction has displaced some amount of reading or writing practice). So that is what it is. I'm pretty much sold on Hartwell's conjecture that speaking/writing grammar and formal grammar are two unrelated skill sets that happen to deal with the same subject (like how Sex Ed. doesn't make you a better lover), but that's because it's the only explanation anyone's put forth that accounts for the data. quote:but since you have frequently confused style and grammar in this thread, maybe I'm just misunderstanding you. Seriously? First off, this conversation won't be improved by our scoring points off each other. Second, grammar and style are very much like things. Both describe rules of usage whose manipulation causes words to mean. quote:It is a very simple fact of English grammar that nouns pluralize, and adjectives do not. How can you possibly claim that your poor has a noun, when *your poors is ungrammatical? If that were truly a noun, pluralization would be possible. Because "poor" is already plural? Because the thing designated by "poor" is in fact a collection of poor people, not one lucky Irishman who was first to the post at Ellis Island? The point I was trying to make is that it is also possible to read this sentence as a series of tropes. "Poor" clearly means "poor people," but we've described the connection between word and meaning differently. You've suggested that "people" has been excised from the sentence but lives on as a hidden noun. I'm suggesting that "poor" is a synecdoche, which means that "people" has not been excised because troping "poor" has made it sufficient shorthand for "poor people," and it therefore functions as a noun within the boundaries of the trope. A better example of this phenomenon might be giving a noun a tense -- conjugating it like you would a verb. Here are a couple examples that use the word "brick." The entrance to the wine cellar had been bricked over by the house's former occupants. I bricked him in the head. In both of these cases, "bricked" is clearly a verb, not a noun. I suppose you could claim that "bricked" is an ungrammatical construction, but that's a difficult case to make when (1) English is full of verbs that evolved in exactly this fashion and (2) there is no reasonable substitute (i.e. I'm not writing "knifed" instead of "stabbed"). And in both cases the meaning is clear. My point with this is that there are multiple, correct ways to describe the structures that give a sentence meaning, and how you describe these structures depends on what you want to do with them. I mean, a zoologist, a veterinarian, an ecologist, and a butcher all see a cow differently. That doesn't mean it's not a quadruped, doesn't have pinkeye, doesn't kill of fish by flooding waterways with recycled grass, or isn't steaks.

|

|

|

|

I think your concept of what "grammar" is is different from what a linguist would call "grammar".

|

|

|

|

quote:So that is what it is. I'm pretty much sold on Hartwell's conjecture that speaking/writing grammar and formal grammar are two unrelated skill sets that happen to deal with the same subject (like how Sex Ed. doesn't make you a better lover), but that's because it's the only explanation anyone's put forth that accounts for the data. That sounds a lot like Chomsky's competence/performance distinction, which has been a staple of linguistics for at least the last 50 years. (Modern discussion of this idea uses the terms I-language and E-language.) quote:Second, grammar and style are very much like things. Wow. We live in totally different worlds. Consider this: I'm kinda pissed that happened. This is a perfectly grammatical sentence. This is an inappropriate sentence in a formal setting, and is not acceptable in any kind of standard writing. Considerations of style are not the same thing as considerations of grammar. Also consider this famous sentence from Chomsky: Colorless green dreams sleep furiously. This sentence is meaningless, yet entirely grammatical. The fact of something being grammatical can be unrelated to the meaning or style. quote:I'm suggesting that "poor" is a synecdoche, which means that "people" has not been excised because troping "poor" has made it sufficient shorthand for "poor people," and it therefore functions as a noun within the boundaries of the trope. I don't care how you choose to read it. That doesn't affect the underlying syntactic structure of the sentence. Categories like "noun" and "verb" are morphosyntatic categories. They are not rhetorical, stylistic, or semantic. I think we're going to have to agree to disagree on this. Or take it to another thread. (Or the parking lot!) I'm not sure this discussion is very interesting to the other people in this thread.

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:Sorry to poo poo up the thread on this point, Brainworm. I'm actually quite interested in most of it. I like reading your posts on how you interpret various works. We just have totally different background in language analysis. As a linguist, I feel compelled to comment on your analyses that I disagree with. This conversation's pretty far from a threadshit, and I think it might be one of the more useful conversations here. I mean, imagine someone who doesn't work with language. I like to pick on engineers, so I'll choose one of them. I imagine that he might think that English (Lit., Rhetoric and Composition, and Creative Writing) and Linguistics are similar fields, when they're really as unlike as, say, Physics and Chemistry. We make completely different assumptions about how language makes meaning. I'm going to say that the foundational structures of language (or at least English) are basically tropic, and I'm going to organize grammar around ways of understanding tropes. You're (probably) going to say that the foundational structures of language emerge from a rule-based grammar, and orbit your understanding of tropes around a series of grammatical definitions. In this Ellis island line we're kicking around, we start with different assumptions and so come to different conclusions. I determine whether something's a noun by looking at what happens inside a synchdotal structure, while you determine whether something's a noun by seeing if it does what other nouns do. Because of that, I have to to ignore (or at least subordinate) the does-it-do-what-other-nouns-do litmus test, and you have to do the same with the trope. So of course we're going to disagree about how this line works (and probably a bunch of other things) the same way a Physicist and a Chemist would disagree about how to spend the piles of grant money they roll around in or how to use classroom clickers more often.

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:I think we're going to have to agree to disagree on this. Or take it to another thread. (Or the parking lot!) I'm not sure this discussion is very interesting to the other people in this thread. That seems like a path of wisdom. Also, I'd like to see tenure lines reallocated on some kind of parking lot altercation metric.

|

|

|

|

So what ended up happening with that dragon thing? Also, is the reason Merchant of Venice is never done as a comedy anymore just because people are uncomfortable with the humor or is it just actually not funny? I was listening to the director commentary for the Al Pacino/Jeremy Irons movie and he just really didn't seem to be able to see the humor in scenes like the one where Tubal turns up to tell Shylock the rumors about his daughter. Personally, I think that would be drat easy to play comically, but it kind of relies on a "stingy Jew" joke. Also, also, and this is assuming you've seen that version of Merchant, what do you think of the homoeroticism in it? According to Jeremy Irons he didn't play Antonio gay, but Michael Radford seemed to have directed him gay. I know that Shakespeare's sexuality was discussed earlier and it seems like everyone came to the conclusion that while you can read some of the sonnets as pretty gay there's no real proof for it and so it seems a little presumptuous to make characters from and Elizabethan play gay. Honestly, I kind of like it. It adds a lot to what is otherwise not a terribly developed character and takes the text in a new direction without resorting to placing it in the modern day or doing something else bizarre. Last question: Who is your favorite Shakespearean actor?

|

|

|

|

Robin Goodfellow posted:So what ended up happening with that dragon thing? The dragon thing is still happening, but it's slowly becoming one of those projects that gradually involves more people for whom it's not a top priority. I forget exactly where I'd left things when I posted my bit about it, but you'll remember that my original conjecture was that the Horsham Dragon was a crocodile monitor or something very like it -- the creature described in Trundle's pamphlet is like a croc monitor in terms of size and some behavior, but this is complicated because the natural behavior of most large monitors hasn't been extensively detailed. For instance, there are reports of croc monitors killing hunting dogs, which the Horsham Dragon also does, but this behavior has never (or not yet) been reliably documented. Either way, there's apparently some disagreement among herpetologists about whether these are croc monitor remains -- some think they are, and some think that this is a previously unknown species, a unique specimen, or some kind of crossbreed. This is a stuckpoint for me. If this is a croc monitor, it had to come from New Guinea, and my job is to find a way for it to have gotten from New Guinea to Sussex in or around 1614 (which is absolutely possible -- the English knew about New Guinea as early as 1600). But if this isn't a croc monitor there's no longer a clear point of origin. And in that case, we probably start playing the doubting and believing game: if these remains are of the Horsham Dragon, how can records of the dragon supplement what we can learn from them? And if they aren't, are there other 15th-18th c. records where this creature might have made an appearance? Right now, I'm not sure what I'm hoping for. Either direction is great, but any non-croc-monitor outcome is a deal more work for me. quote:Also, is the reason Merchant of Venice is never done as a comedy anymore just because people are uncomfortable with the humor or is it just actually not funny? I was listening to the director commentary for the Al Pacino/Jeremy Irons movie and he just really didn't seem to be able to see the humor in scenes like the one where Tubal turns up to tell Shylock the rumors about his daughter. Personally, I think that would be drat easy to play comically, but it kind of relies on a "stingy Jew" joke. There are a few reasons. One is that it's not really funny, at least not in the sense that there are jokes and punchlines; any humor in the play comes from its constantly outlandish situations. That's easy to miss, given a few hundred years of intervening history and that Merchant was presented alongside plays whose plots might be summarized "man sells soul to the devil for invisible pope-punching ability," or "English friar bests German friar in spellcasting contest." But take a minute to think about the actual situations in Merchant. I don't like to do this, but let me summarize the play from my perspective for a second. Skip this if you already know Merchant from top to toe. A Rough Summary of Merchant The play opens with Antonio moping around and a couple of his friends trying to figure out why. They think it's because he's got ships at sea, which is financially risky, but Antonio hits back with a good set of reasons for why that's not what's making him nervous -- basically, he's diversified. These are three ships in three different places, so one disaster isn't going to sink them all. Then one of them suggests Antonio must be in love. Antonio dismisses this ("fie, fie"), but this dismissal looks nothing like his first one. That (and some exposition) are why the first one's there -- to show us what Antonio looks like when he tells the whole truth, and to show us what he looks like when he's hiding something. We can infer that Antonio's in love and can't or won't admit it. And then it gets weird. Bassanio enters and asks Antonio for a loan so he can pretend to be rich to woo Portia, which is exactly how you'd expect this kind of romantic situation (a character in love, but keeping it secret) to escalate -- we've all see the "lover cornered into helping the beloved woo someone else" plot before, and the people in Shakespeare's audience had, too. This just spins it queer, which is the same move you see over and over again in Twelfth Night and in the Sonnets. So Antonio's now playing Cyrano de Bergerac, sort of. Except he's in love with Christian instead of Roxane. And then it gets weirder. Shylock, for reasons that aren't terribly clear,* asks for a pound of Antonio's flesh to secure the bond for the money Antonio's lending to Bassanio. OK. Strange bond. Fair enough. So the play has it's own Cobra Commander -- a guy who not only thinks the Statue of Liberty is a problem, but a problem that's best solved by, say, melting it with acid dropped by a fleet of zeppelins painted to look like snakes. And then you find out that in order to marry Portia, Bassanio and the other suitors need to solve this casket riddle her dad left behind. So it turns out Shylock isn't the play's most indirect thinker. And Portia's cool with this, which is strange. Any other Shakespearean heroine would leg it away from that kind of crackrock setup the second dad was in the ground. Think about how Cordelia acts in Lear -- she's a good daughter precisely because she disobeys her father, since he's the kind of father who turns love into some kind of ceremonial contest. And then it gets weirder. Antonio defaults on his bond, so the clear solution to his legal predicament is for Portia to dress up as a young, male, expert witness -- a doctor, to be precise -- who nobody invited to the trial in the first place. Why the crossdressing? Who knows. It's not for credibility -- in All's Well, Helena is France's foremost medical practitioner, so the idea that women couldn't be respected medical professionals (at least on stage) is off the table. Maybe Portia just likes pants. Or maybe she went to the same Waldorf school her father and Shylock did. And then it gets weirder. Bassanio thanks the still-disguised Portia (who he doesn't recognize!) and promises her anything she wants in repayment. So the cross-dressed Portia asks for a ring she'd previously given him and made him promise to never give up. In other words, Portia seems aware that Bassanio and Antonio have a close relationship (Bassanio skips out on their honeymoon so he can get back to Antonio), so she forces him to choose who he's more loyal to. Turns out it's Antonio. Bassanio gives the crossdressed Portia the ring he's promised never to part with as payment for saving Antonio's life. So she whips off her disguise and lectures him, and Bassanio promises to do better (actually, Portia makes Antonio promise he'll make Bassanio do better). And Antonio find out his ships have safely arrived which, if you remember the play's opening, he doesn't seem to much care about. The Rough Summary Ends I know that's a lot of Merchant, but it should make something pretty clear: Merchant is a little surreal, and more than part parody. The relationship between Antonio and Bassanio, however you cut it, is basically a stock romantic comedy plot spun around two men; Act V brings that home in spades. We've all seen the romantic comedy love triangle situation where some guy has to choose between two women (or some woman has to choose between two guys). Shakespeare just spins this familiar scene queer (just like in Act I). So the play has a great deal of comic potential that way. But it's not often exercised because Merchant has slowly become The Tragedy of Shylock. That is, I've seen productions that entirely cut or severely abbreviate Act V (with Portia and the ring) so that the play's arc is redescribed as the abuse and fall of Shylock at the hands of institutional antisemitism. Regardless of whether Act V is abbreviated, this reading of the play now seems mainstream. This is a bit ironic, since if the play is about the systematic abuse of any group, it's probably homosexuals. Yes, Shylock ends badly, but he's also evil. Maybe justifiably so, but there's no question that he deserves at least most of what he gets. I mean, before Portia shows up, he's about to commit premeditated murder with the blessing of the court. But Antonio is actually pretty pathetic -- and I mean this in the sense of evoking pathos, not in the sense that he's contemptible. Even though he doesn't want Bassanio to marry, he risks his life to help make it happen. So his love for Bassanio is one of those noble kinds. You know, set it free and blah blah blah. And what does he get in return? The first thing Portia does once she's married is split up Antonio and Bassanio. They can't even be friends, apparently -- at least not without her permission. That seems a little callous since she (a) knows they're close and (b) Antonio risked (and nearly lost) his life to arrange their marriage in the first place. She never even thanks him. In fact, all she does at the end of the play is tell Antonio that he's going to get some of his own money back (his three ships have arrived, finally). So she's insensitive and cheap. So the play ends with Antonio having hazarded his life, and for what? He got his ships back, sure, but that wasn't really by dint of his actions, wouldn't have been an issue if not for his bond with Shylock, and doesn't (based on his reasoning in Act I) seem to worry him much in any event. On the other hand, he's lost his best friend to a woman who's just as insane and controlling as her father. quote:Last question: Who is your favorite Shakespearean actor? I like Patrick Stewart, and I've said before this that he could be the Lear of a generation. But Kevin Kline, particularly in his Hamlet, is very, very good. Maybe the best Shakespearean film actor going. * Yes, he hates Antonio. But he also hates everyone else, with the possible exception of Tubal, and it never seems to occur to him that he could (a) hurt Antonio by not making the loan in the first place (since it seems nobody else will loan him money) (b) take a more conventional revenge, e.g. use a few of those 3000 ducats to hire some goons to work Antonio over with bike chains.

|

|

|

|

So do you think that Shakespeare had no intention of raising the issue of antisemitism? I mean, he was a pretty politically savvy guy and hadn't there just been some plot of poison the Queen which her Jewish doctor was falsely accused of being involved in? Last time I studied Merchant in school was 9th grade, so that might be wrong though. Your summary was hilarious and the rest of the answer was really excellent as well. How do you feel about people who like to say that they are Falstaff? Personally, everyone I've ever known who thinks that Falstaff would be their Shakespearean alter-ego has been a total dickwad. Any other interesting cryptozoological cases you can tell us about?

|

|

|

|

Robin Goodfellow posted:So do you think that Shakespeare had no intention of raising the issue of antisemitism? I mean, he was a pretty politically savvy guy and hadn't there just been some plot of poison the Queen which her Jewish doctor was falsely accused of being involved in? There was a plot, and the doctor in question was Rodrigo Lopez. And he was Jewish. But he was also Portuguese, and that has at least as much bearing on his status as his Jewish heritage,* since at this time the English largely saw Portugal as a Spanish puppet kingdom -- this comes across in the relationships among the court in Kyd's Spanish Tragedy, for instance. Second, court politics saw innocent people executed all the time, regardless of their religious leanings. Deveraux (the guy who accused Lopez) was wrapped up in more than a few of these, as was his son Dudley (the Earl who rebelled against Elizabeth in 1601). Politics was played for keeps in Tudor courts. There are also two larger issues that inflect this. The first is the political situation of Jews in England at this time -- the book to read on this is James Shapiro's Shakespeare and the Jews. Put simply, there weren't many Jews in Shakespeare's England (but more than some historians have thought) because of their expulsion by Edward the Confessor (which may not have happened). The second larger issue is that the Renaissance predates the Enlightenment. Simply put, the idea that people are somehow politically and socially equal, that they have inherent rights, is not in circulation during this time period. So anti-semitism, like racism, is a bit of a historical contradiction in terms; there's no set of political ideals that counter it. If you asked an Englishman from this period whether Christians were better than Jews, he's say, "of course, and for the same reasons that members of the Church of England are better than Muslims and atheists. Of course Catholics and Puritans aren't Christians any more that Jews or Muslims are, so when you say 'Christians' I assume you mean Anglicans." This is how Marlowe handles his Jew, Barabas; he's surrounded by Catholics who are at least as evil and not nearly as smart. So there's institutional discrimination at work, but not the kind of institutional discrimination you see in a post-Enlightenment world. If Queen Elizabeth sends you to war and you get captured, you're a slave. If you have kids, they are, too. Why? Wrong place, wrong time. Tough poo poo. There doesn't need to be any kind of justification for this. But once you throw out an idea like "all men are entitled to freedom," slavery has to negotiate a way for slaves not to deserve the freedom others are entitled to. That kind of discrimination looks totally different. So political savviness really isn't on the table; you can't expect that Shakespeare's going to develop and adopt a way of thinking about people's rights that wasn't on the table for another two centuries, and it's probably a strong misreading of Merchant to suggest that Shylock was a victim of discrimination. Sure, he experiences discrimination, but during the Renaissance, that's like getting caught in the rain -- it sucks, but it's not a case for moral outrage. quote:How do you feel about people who like to say that they are Falstaff? Personally, everyone I've ever known who thinks that Falstaff would be their Shakespearean alter-ego has been a total dickwad. I have never knowingly met such a person, but I'd imagine anyone who wanted to be an unrestrained glutton, indiscriminate womanizer, and shameless coward would make poor long-term company. quote:Any other interesting cryptozoological cases you can tell us about? Not so much. I've got a scattering of cases that range from the mildly interesting to the shamelessly bizarre. I can say with confidence that Renaissance ballad and pamphlet writers were close to obsessed with the generative organs of any new and unusual animal. "God," they would say, "I've never seen a creature so glorious. If it was smaller or had fewer pointy bits I'd totally grab its junk." * He, like other Jewish immigrants, converted to Christianity on or shortly after immigrating to England Brainworm fucked around with this message at 00:59 on Jun 3, 2009 |

|

|

|

In that case what's Shylock's famous speech all about and where did the inspiration for it come from if Shakespeare wasn't ahead of his time? I don't know if I would say that it's moral outrage that he's expressing there, but it's definitely frustration with the system of justice. I suppose though that if Shylock is meant to be a bit of an outrageous character, what with the whole pound of flesh thing (which seems justified and fairly sane in the movie, but isn't in the text), then that speech could be read as "Oh jeez, there he goes again with his wacky ideas." To me Shakespeare does seem to have a sense that slavery and other forms of discrimination are unjust, though. It comes up again during the trial scene of Merchant but also in The Tempest, Othello and Titus Andronicus. Of course, I don't have any particular knowledge of how Moors (or other social inferiors) were portrayed by writers of the time so it's totally possible that Shakespeare's depiction of them is not out of the ordinary. You've already mentioned Barabas and from what you've said it seems fair to compare him and Erin, so clearly there's no problem with showing other races/religions/etc as intelligent, but does Barabas have the same influence and power that Erin does? As for The Tempest, I always feel that the audience is quite pleased when Ariel is released at the end and that Caliban's issues are partially Prospero's fault. Othello pretty much opens with racism (Oh my god, my daughter/girl I like is married to a black guy) despite the fact that Othello is well respected. I would assume that Shakespeare was doing this intentionally. I know you said that you haven't seen Ian Mckellen's Lear yet, but I think he could maybe beat Patrick Stewart. Of course the ideal thing would be having them both in the same show. Unfortunately, I can't think of one that calls for two old men.

|

|

|

|

Robin Goodfellow posted:In that case what's Shylock's famous speech all about and where did the inspiration for it come from if Shakespeare wasn't ahead of his time? I don't know if I would say that it's moral outrage that he's expressing there, but it's definitely frustration with the system of justice. I suppose though that if Shylock is meant to be a bit of an outrageous character, what with the whole pound of flesh thing (which seems justified and fairly sane in the movie, but isn't in the text), then that speech could be read as "Oh jeez, there he goes again with his wacky ideas." I hear where you're coming from. Basically, there are a couple distinctions that maybe we need to make. Just because, say, slavery is fine and dandy in Renaissance England doesn't mean that individual slaves are happy with their lot or that everything that happens to them is connotatively neutral. In other words, just because we predate a moral objection to slavery doesn't mean that slaves can't be sympathetic characters. They (and servants) can be incredibly sympathetic (especially when they, say, get beaten). But the moral precepts that pathos is built on aren't "this person is a slave, slavery is unjust, and that slave therefore has a moral imperative to emancipate himself." It's more like "that person is a slave, which is a shame because his position allows his mistreatment." The point, in other words, is that sympathy for a slave is not the same thing as an indictment of slavery as a system. Those ways of thinking only hitch wagons during the Enlightenment. The same thing is basically true of Shylock. Shylock may be a sympathetic character because he's mistreated, and he may be mistreated because he's a Jew. But that doesn't mean that sympathy for Shylock is an indictment of antisemitism. In the Renaissance, people aren't equal and that's tough poo poo. But that doesn't mean you can't sympathize with them when bad things happen. In the case of Shylock specifically, though, we shouldn't confuse motives with justification and pay out sympathy where it's not totally due. Shylock hates Antonio because Antonio (like other Venitians) mistreats him. And Antonio has every right to do this. He's of a higher social station than Shylock and can spit on him, call him dog, and all the other lovely things that make him a good Christian. But that doesn't mean that Shylock's "hath not a Jew eyes" is an implicit claim that he and Antonio are equals because religious difference is no basis for social hierarchy. Shylock instead claims a common humanity with Antonio. We all have eyes, we all feel pain, we all die, so don't treat me as less than human even if you treat me as less than a Christian. But that's clearly undercut by his conduct. Shylock isn't interested in mercy or forgiveness, and he's not interested in equality -- look at how he reacts when his daughter elopes, or how he acts in the courtroom. Sure he hates Antonio, and he has reasons to hate Antonio. But that doesn't mean we should feel sorry for him when he doesn't get to cut up Antonio on the courtroom floor. Put another way: like Richard III, Shylock has reasons for the things he aims for. That's not the same thing as presenting moral ambiguity. I mean, Richard tells us that he's murdering his way to the throne because he's deformed and can't get laid, but that doesn't mean you can sympathize with him. Shylock's in an analogous situation. He tells us, more or less, that he's going to trick Antonio into a lethal bond; it's only historical accident that makes Antonio's discrimination against Shylock's religion more repellent to modern readers than everyone's discrimination against Richard's deformity. quote:To me Shakespeare does seem to have a sense that slavery and other forms of discrimination are unjust, though. It comes up again during the trial scene of Merchant but also in The Tempest, Othello and Titus Andronicus. I don't think Shakespeare had that sense, although the texts very well might -- that is, the fact that you can find a thing in a text does not mean that it was historically available to the author. Caliban's servitude is a good example. Prospero shows up, kills his mom, enslaves him, and claims the island as his own. From a modern perspective, there are clear moral ambiguities here because we believe that colonization, regardless of scale, is categorically morally wrong. Renaissance England clearly did not. They did it with gusto, and with no internal debate about ethics. But even if you look at voices from this period who are critical of colonization, you don't find any hint of an institutional critique. Bartolomé de las Casas, for instance, objects to torture,* but has absolutely no qualms about using military force to take native land. Likewise, racial indictments function at a personal, rather than an institutional level. When Brabantio accuses Othello of using witchcraft to seduce his daughter, the senators don't call Brabantio a racist. And neither does Othello. They wait for Desdemona to show up and tell her side of the story. The other racial epithets you see have a similar quality; the logic behind them isn't "Othello is black and therefore incompetent," they're more like an angry child reaching for whatever insults are available. I mean, calling someone stupid doesn't necessarily suggest that you have some categorical aversion to stupid people -- that, say, you don't donate to charities that support the mentally handicapped. It could just mean that someone else is a big doodoohead. We've also got to remember that we see race as the significant cultural difference between Brabantio/Desdemona and Othello. There are at least a few others that, historically, may have mattered much more. Religion is an obvious one -- Othello is of course Muslim. And so is age. Othello appears to be near the end of his military career, and he's Brabantio's friend (incidentally, another reason for Brabantio to be upset). And there's another big one. Brabantio is a member of the social elite, and part of that menbership involves arranged marriages. Think of how Kate's father works in Taming or Capulet works in Romeo and Juliet. There's a good case to be made for Brabantio being upset that Desdemona married in secret to anyone of any age or any race; her marriage is his business, not hers. This is pretty clear when he and Iago talk about his daughter's eloping as a robbery, but even clearer once Brabantio cools off and talks to Othello about Desdemona: she betrayed me, he says, so she may betray you. You get much more of this kind of talk from him than you do talk about age or race or religion, but it's easier to miss because this system of brokered marriage entitlement has fallen out of use. And Titus? When Aaron asks "is black so base a hue?" the answer is a resounding "yes." The logic isn't that Aaron is black and therefore evil; it's that Aaron is both evil and black, and that his child's skin color clearly means it's his and has to die. Not because the baby is black and therefore evil, but because killing the baby seems like the best way to punish Aaron. You get the idea. When you see something that looks like the rejection of a modern form of institutionalized discrimination in Shakespeare, re-read it. You'll always find something else in play. quote:Of course, I don't have any particular knowledge of how Moors (or other social inferiors) were portrayed by writers of the time so it's totally possible that Shakespeare's depiction of them is not out of the ordinary. This needs some clarifying. Moors were not social inferiors. They were non-Anglican, and the worse for it from the English viewpoint. But the English were very conscious of Moors representing a wealthier, larger, and more technically and militarily advanced civilization. Remember, this is not the British Empire that the sun never sets on -- that's more than two dynasties and two civil wars away. So the attitude of the English toward Muslims at this time was generally respect, fear, and some irritation at the religious conversions of opportunistic English merchants. But the secure, institutional bigotry that we'd associate with the colonial and post-colonial world just isn't there. * So do the English. In fact, the English generally called waterboarding "torture" in the early 17th century.

|

|

|

|

Pedagogy question: A friend whose skills I respect very much, who also happens to be a graduate student teaching in the same program I am, has a unique and brutal technique for his freshman comp classes that I am dying to implement: The Wall of Shame. Basically, after every "final" paper (this is a writing-intensive, revision-heavy program we're pushing here), he puts a few excerpts of the most egregious or illustrative errors up on the overhead (anonymously of course) and makes examples of them to the class to talk about. Of course, his students either love it or hate it, but according to his evaluations most come around to understanding that even if it's humiliating, they'll never make that mistake again. So my question is, in your opinion is this too brutal to do to my freshmen? Is it as beneficial as it seems, or would I be undermining something important that would hurt our general learning goals? If not how would I have to present it for best results/least resistance? (I'm of the opinion that since my arrogant rear end got humiliated weekly in tutorials, they can definitely learn from a little tough love.) Additional concern: what if I'm running the type of class where students are very exposed to each others' work (not just through one on one peer reviews, but where everyone's drafts are accessible in an online portfolio system)? Would this make it impossible to keep Wall of Shame anonymous? Does it matter?

|

|

|

|

Defenestration posted:So my question is, in your opinion is this too brutal to do to my freshmen? Is it as beneficial as it seems, or would I be undermining something important that would hurt our general learning goals? If not how would I have to present it for best results/least resistance? As an undergraduate I can tell you that I find this technique both hilarious and useful. Given how little attention high schools give to basic grammar and writing techniques I think that beating it into them would be the most effective way. After all, freshmen are concerned about fitting in and being accepted more than anything else. If you scare the poo poo out of them they'll be sure to never make the same mistake again.

|

|

|

|

Thanks Brainworm, I was having trouble understanding the difference between respect for humanity and respect for social differences, but I think I get it now. I think I'm going to read the Henriad next as I've never done any of the histories and you seem to recommend them. Should I read them in order? One more, and this is kind of a staging question, but can you shed any light on how Ariel makes the food disappear in III.iii? I'm pretty interested in any sort of cool effect like that, so is there any book you can suggest about Elizabethan staging?

|

|

|

|

Sorry Brainworm, but I disagree wholly with your assertion that Shakespeare is not questioning antisemitism. First off, let's consider Shylock as the villain. Unlike Barabas in the Jew of Malta, Shylock is not some stock character who is evil for the sake of being evil. His hatred for Antonio arises from a very clear list of abuses the usurer faced from the businessman, including being spat at, being kicked, and perhaps, most importantly and ironically, having his own trade mocked, since usury is Shylock's livelihood and his only means of survival. To simply say he hates everyone but Tubal is to overlook many important subtleties in Shylock's character: the society refuses to recognize his humanity, they attack him in every way possible, and they denigrate all that he has sacred. For instance, his anger at Jessica comes from the fact that she has basically rebelled against him in every way possible: not only did she sacrifice her religion and her culture for those of the people who seek to destroy Shylock, but she also sold the ring Leah gave to him when he was a bachelor for a monkey. The ring is important because we see Shakespeare directly counteracting the stereotype as Jews as the money obsessed people (which Solario and Solanio echo in act 2 scene 8. Remember, we only hear about Shylock crying out for his ducats from these two characters, and seeing how the other bit of information we receive in this scene, Antonio's ships sinking, is wrong, it does bring into question the veracity of their claim). Shylock holds a strong sentimental value to the ring, and Jessica's trading the ring for a monkey symbolically destroys his entire family for a simple pet (which we never see or hear of again). One of the biggest points you miss is that ANTONIO WILLINGLY TAKES THE BOND FOR A POUND OF HIS FLESH. He agrees to it! If Shylock didn't have to offer the bond, Antonio didn't have to take the bond. We cannot look at Shylock with pure condemnation and then not chastise Antonio for getting into the bond. It's an example of Christian hypocrisy. They mock the Jews for being driven by money, but yet look at the Christian society. It is actually driven by money and trade. Compare Shylock's ring with Gratiano and Bassanio's rings. While Shylock wouldn't give it away for anything in the world, Gratiano and Bassanio hand their's over despite the promise they made to their wives. Bassanio values Antonio's input more than a promise he made to his wife. Then let's look at Bassanio's courtship. Why does he attempt to woo Portia? Is it for love? No! It's because she can pay off his debts and so he can keep up his gallant lifestyle! If she wasn't rich, he wouldn't be pining for her. There are examples of marriage for love in this play, so we can't just write it off as the "marriage is a business contract" trope. So, throughout the play, we have a Christian society that is so obsessed with money, they would willingly allow someone else to murder them so they can provide it. And Shakespeare isn't attacking the Christian's condemnation of the Jews? Now, we get to the question of mercy. Shylock shows Antonio no mercy in the courtroom, despite the fact that the Christians all but demand it from him. Yet, when the Christians have the upper hand, what do they do to Shylock? Do they show him any mercy? No! Instead, they kill him! While they don't directly execute him, they take away his goods and possessions, and then they force him to convert to Christianity. This has a great impact on him: he loses all of his connections and friends, he can no longer live in the Jewish ghetto, but the Christians will never accept him. Most importantly, he loses his livelihood. He now has to try and etch out a living with practically nothing. You can argue that Antonio shows Shylock mercy, but remember, what mercy is it. He forces Shylock to become a Christian. Then, he requires Shylock to give HIS half of Shylock's possessions to Jessica and her husband. What is the Christian example? Revenge. Remember, Shakespeare was possibly a Catholic or at least a Catholic sympathizer, so I doubt he would be one to not attack the Elizabethan notions of humanity and right and wrong. When you really begin to peal apart Shylock, especially compared to the Christian society around him, you begin to uncover a villain whose plight we pity rather than take delight in. I really think your analysis of the play ignores a lot of the damning evidence against the Christian society around Shylock. Perhaps the Merchant of Venice attacks Christian morality more than it defends the Jews, but I do believe that Shakespeare argues against the denigration of a whole group of people just because of their religion. Edit: One final point. Shylock is interested in revenge. Remember, Jessica's marriage isn't just a defying her father, it's betraying her father. She goes far beyond just running away with a Christian. SHE STEALS FROM HER FATHER. Shylock believes the Christians obviously corrupted his daughter. Antonio is Shylock's one true chance to hurt the Christians, his only chance to get revenge. I honestly believe the bond for a pound of flesh was a mockery at Antonio. Remember, Antonio is so averse to money-lending with interest but yet, he willfully takes a loan with interest when no one else will give him credit (Remember, Antonio says that his credit is stretched very thin). Also, Shylock has no way of knowing what misfortunes will befall Antonio, so thuse he couldn't give out the forfeiture with any reasonable desire to collect on it. The pound of flesh (which is an Italian story) is Shylock's way of insulting Antonio, sort of a way of saying "you're so desperate that you need to go to a Jewish money lender." By the point that we reached the courtroom scene, so much has escalated. Shylock has had his family destroyed by Jessica's betrayal. The bond has grown beyond money. Shylock will not take the 6000 ducats, or even 36000 ducats because he wants to get revenge on the Christians. Remember, they have shown him no mercy during his the play. They have attacked him verbally, they have stolen from him, and now, he has his chance to get back. Remember, Shylock does not exist in a vacuum. Shylock is an example of a desperate man who acts evilly because it is the only way he can get back at the society. I can't say he is a good character. We don't have that in the play. But we also don't have someone who is evil because they are naturally evil. Cemetry Gator fucked around with this message at 14:21 on Jun 3, 2009 |

|

|

|

Defenestration posted:Pedagogy question: A friend whose skills I respect very much, who also happens to be a graduate student teaching in the same program I am, has a unique and brutal technique for his freshman comp classes that I am dying to implement: The Wall of Shame. I've used this a few times, and it can really work well. But there are a few caveats: 1) Your class needs to have a good rapport. You can tell that's the case when you put up an anonymous example and somebody's like, "yeah, that was me." If you're doing this exercise that's not happening, you're burning good will. This also covers the anonymity bit. If you've got a good enough rapport with your class, anonymity's basically irrelevant. If you don't, I wouldn't run the exercise at all. Rapport is a funny thing, though. This doesn't mean that every student likes you, exactly. It just means that you've built a community of learning that students trust you (and each other) to maintain, so they're comfortable copping to or volunteering problems they're having. This doesn't mean that you have to be kind or nurturing, exactly. In fact you want to have something like the opposite in play; a mentor of mine liked to say that the classroom should be a "safe and dangerous place," and I think that's about right. One of the best evaluation comments I got last semester was that being in class with me was like being in the room with a loaded gun -- there was a kind of responsibility you had to exercise all the time, and that's exactly what made it fun. That's exactly the tone you want. 2) I would change the name. Not because you don't want this to sound like an exercise in humiliation, but because humiliation's unavoidable and you want to short-circuit it. You know, yeah, you're embarrassed, and the appropriate response embarrassment is to not take it seriously. Now for us, "Wall of Shame" probably does this already. It sounds a bit antique. But it's not going to be that way for Freshmen, where only the most literate have an ear for subtlety. You want a mockable name for this exercise. The Wall of Doom, maybe. Maybe the Wall of 1999,* and have the students critique the writing sample using comparisons to that year: "This paragraph's like Hanson -- all the sentences look alike, and the effect is a little catchy but mostly irritating." Anything you can to spread the embarrassment around. 3) Make sure you're discussing the writing and not the writer -- that is, immediately cut down any "was he too lazy to proofread" action. 4) Choose problems common to at least a quarter of the class. Smaller fractions you deal with in small groups or individual conferences. Widespread problems will generally be stylistic and lead to debate about the best fixes, which is where you want class discussion to go. 5) Allow students to anonymously opt out. Explain a class or two before that you're going to put writing samples from papers on the overhead so you can talk about them as a class, that anybody who doesn't want his or her work to go up should email you, and that opting out won't affect their final grades. Nobody has ever opted out, but it gives a sense of fair play. The tenor of this exercise, in other words, should be collaborative improvement, not the punishment of individual offenders. In order for that to work, you need to shape this exercise so that any embarrassment students feel is directed someplace useful -- you're doing harm if this makes any student resent the class or its subject matter. And rapport, rapport, rapport. This is not an exercise to use in a room full of kids who don't yet know you (or each other) or don't trust you. So for Freshmen, I'd pocket this for the first six weeks, probably, unless the group seems really cohesive from the start. For upper-level writers you can dump some of the caution. * I would probably not do this. We generally compare writing samples to babies and puppies.

|

|

|

|

Robin Goodfellow posted:I think I'm going to read the Henriad next as I've never done any of the histories and you seem to recommend them. Should I read them in order? I'd read Richard II-Henry V in order. I'm not sure what to recommend about the Henry VIs. They're like scripts for action movies because, well, that's almost exactly what they are. They work much better on stage or screen or even as audio dramas. So you can read them if you want, but the battle sequences won't be engaging unless you have a vivid imagination. Most people skip them and read Richard III as a standalone play, which I can understand. But Richard is actually way better in 3 Henry VI, especially in the final scene where he kills Henry, who's been living knee-deep in poo poo and rainwater since his prison cell's the tower basement. It's chilling in a way that no scene from Richard III ever quite manages. quote:One more, and this is kind of a staging question, but can you shed any light on how Ariel makes the food disappear in III.iii? I'm pretty interested in any sort of cool effect like that, so is there any book you can suggest about Elizabethan staging? I can think of a few possibilities. The first is that the banquet is set on a table at or around center stage. Ariel makes the banquet disappear by covering it with a blanket, after which a stagehand opens a trap door beneath the table. Presumably his body muffles the crash. A variation on this would be to set the table at rear center stage and pull it into the discovery space (the curtained area at read center where Polonius (probably) hides while he eavesdrops on Hamlet and Gertrude). The late date of The Tempest also means that it's possible the play was performed indoors at Blackfriars, which puts a few more options on the table. Blackfriars was lit by candles, so it was possible to cast very heavy shadows on stage by means of simple blinds, so a dense shadow could do the same as a blanket and to much more interesting effect. It's also possible, though unlikely, that a custom prop would have been built for this effect, though this would be marginally more likely at a higher-end venue like Blackfriars. That opens up tons of possibilities. I know two good books on this. The classic is Dessen's Elizabethan Stage Conventions, but I like C. Walter Hodges's Enter the Whole Army.

|

|

|

|

You've talked a lot about tropes (especially synecdoche and metaphor). Have you ever read Kenneth Burke's A Grammar of Motives and are you familiar with his master tropes? It might interest you if nothing else because you seem to have similar views on language use. Maybe you should have been a rhetorician?

|

|

|

|