|

Your Proud Pal posted:Apologies if this has been addressed already, but I've always been curious to get a Shakespeare scholar's thoughts on the ideas of Hamlet expressed by Stephen Dedalus. I've listened to Joyceans talk a lot about it, and its significance in Ulysses, but I've always wondered how a Shakespeare critic would approach it if it were expressed by an actual person, purely on Shakespearean terms. In all honesty, it's been so long since I read Ulysses or Portrait (or Dubliners, if you're one of the crowd that puts Stephen as early narrator) that I can't say anything solid about it right now. And I unfortunately won't have copies of either on hand for about a week, since I'm still out of town. But if this is a conversation you want to start, I'll re-read each of them once I get back. I should do this anyway.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 10, 2024 08:01 |

|

Doran Blackdawn posted:I believe you mentioned before your thoughts on Othello, specifically, the lack of motive for Iago. At the time you posted it, I thought you simply weren't giving the "he was a racist" hypothesis a chance, but after reading your discussion with Cemetry Gator, I'm having great doubts believing it myself. You and every Shakespearean critic since Coleridge. I'm not as certain about Iago as I am about, say, Hamlet. I'd write better books if I were. But any grammar of motives needs to account for Iago's actions both during and leading up to the events of the play. In no particular order, these include: Electing to Othello's service in the first place. Iago's a mercenary, after all, so he has a choice of armies. I've always presumed that, were Iago's motive simple bigotry, the play would have never happened. Iago's relationships with Roderigo, Cassio, Desdemona, and Emilia. Specifically, Iago seems to really loving hate Cassio and Roderigo. Maybe not as much as he hates Othello, but it's worth noting that he both destroys Cassio's reputation and arranges his murder -- something that, despite the intricacy of his plotting, he never allows his revenge against Othello. Also, there's Iago's dream. Obviously, this is part of his plot against Othello, but its content is shaped a little oddly: Iago posted:In sleep I heard him say 'Sweet Desdemona, And we can't forget Roderigo. Again, he bleeds Roderigo dry and arranges his death when he's no longer useful. This seems a tangential matter, but it still involves a few murder plots and (let's not forget), Iago/Roderigo episodes both lead the play and frame several scenes. And I think that if you count, you'll see that Iago spends at least as many lines talking to Roderigo as he does to Othello. Also, Iago's marriage is strange. I wish I could be more specific about this, but we only really see enough to get that Iago doesn't seem terribly attached to his wife. At the very least, he's careless of her feelings. Iago's declared motives have a tenor of betrayal. Iago basically lays out four motives for his plotting: He's been passed over for promotion, Othello may have slept with Emilia, Cassio may have slept with Emilia, and he (Iago) is in love with Desdemona. Betrayal seems to be the only thing that all these have in common, although it's worth noting that three of the four are both have a sexual component and are unverifiable (that is, we know for sure that Iago hasn't been promoted, but there's no clear moment where we get circumstantial confirmation for the other three). So there are a few ways to approach this. If my amateurish observations of people* are admissible evidence, I'd seriously suggest starting with the idea that Iago's deeply sexually confused, and that part of his confusion involves negotiating his desires. Or I can just say he's a self-hating queer and make things simpler. That is, Iago constantly confuses personal, homosocial, and homosexual bonding, attraction, and rejection. So an Iagologic of personal relationships goes like this: I admire Othello as a military commander and so chose to serve with him, but his promotion of Cassio over me is a personal/romantic betrayal rather than an underestimation of my virtues as a commander, and so warrants personal revenge rather than professional appeal. In other words, Professional Admiration = Personal (Romantic/Sexual) Attraction, and Professional Rejection = Romantic Betrayal. Or, in shorter words, Iago's not gay, but he'd go gay for Othello for the same basic reasons men of my dad's generation might have gone gay for Elvis. A variation on this theme explains Iago's hatred for Cassio. Maybe Iago's actually attracted to Cassio and reads Cassio's whoring around or acceptance of promotion as a similar kind of betrayal, or maybe Iago has a similar relationship with all his bosses. Who knows? But either way, you get to a sort of repressed attraction of Cassio that comes out in Iago's dream. So Iago hates himself for this. Maybe this is because he has a moral objection to his attraction, or maybe his attraction governs his actions through a more complex psychological mechanism. Either way, this gets us to a deeply-rooted self hatred. In case I'm not far enough off of solid ground, let me suggest that self-hating people get off on betrayal from both ends. They like betraying people because this validates their readings of themselves as bad people (of course I cheat on my girlfriend; I'm morally bankrupt), and they like being betrayed because it validates their readings of others' opinions of them (e.g. of course my girlfriend cheats on me; I don't deserve fidelity). I don't think it matters whether sexual confusion causes self hatred or vice-versa. What matters more is that they go hand in hand. Self-hating people sexually dysfunction, and sexually dysfunctional people hate themselves. Mixing these ingredients together get us what I think is a compelling dramatic psychology for Iago. He sees someone he can take advantage of (Roderigo) and does it. Why? Because he gets off on validating his picture of himself as morally corrupt. Iago imagines his wife loving his bosses. Why? Because their professional "betrayals" of him are in his mind indistinguishable from personal ones and, more important, Iago likes the idea of being betrayed. Iago loves Desdemona. Why? Because he likes the idea of being terrible enough to engineer indirect revenge against a woman he loves, instead of one he barely knows. Iago imagines being attracted to Cassio. Why? Same reason. He would rather engineer the personal destruction of someone he loves than someone who's incidental. So this is a Dr. Phil level analysis, but I like it because it's both interesting and has some explanatory power. Simple bigotry really doesn't have either. * Students.

|

|

|

|

I take it from the thread that you're Stratfordian. Personally, I find Oxfordian theory very convincing, even though there will likely never be any direct evidence. In Harper's a long time ago (when I still read Harper's) there was a debate betwen the two sides. The Oxfordians laid out all the parallels between De Vere's life and Shakespeare's work, all circumstantial. The Stratfordian arguments seemed to run along the line:  "Of course he was a glovemaker's son. Anyone who argues otherwise is an elitist snob!" What are your chief criticisms of Oxfordian theory? "Of course he was a glovemaker's son. Anyone who argues otherwise is an elitist snob!" What are your chief criticisms of Oxfordian theory? What do you make of this outfit? And Sasquatch in general? Brainworm posted:Remember, this is not the British Empire that the sun never sets on -- that's more than two dynasties and two civil wars away. You read The Cousins Wars?

|

|

|

|

Great thread so far! I just started on Julius Caesar, do you have anything I should be looking for or thinking about in particular while reading it? I have already seen it performed so I don't have to worry about spoilers. One thing that has already confused me is why the other plotters want Brutus on their side so much, the plan to kill Caesar doesn't seem that complicated and Brutus manages to screw it up by not killing Antony, so why include him in the first place?

|

|

|

|

OctaviusBeaver posted:Great thread so far! I can clear this up, because it's a historical detail as well as a dramatic one. Basically Marcus Iunius Brutus was a HIGHLY respected Roman patrician, and therefore a good person to have on your side. He was renowned for his character, he came from an extremely old and powerful family, and he had a lot of cash. They think that his participation will lend a lot of credibility to their cause, and it honestly did. Didn't do much good in the end, of course, but they certainly wouldn't have had nearly as much of a chance without him.

|

|

|

|

JIR499 posted:I take it from the thread that you're Stratfordian. Personally, I find Oxfordian theory very convincing, even though there will likely never be any direct evidence. [...] What are your chief criticisms of Oxfordian theory? I've never understood the motives behind anti-Stratfordian arguments, and the Oxfordian one is particularly ridiculous. Edward de Vere (Oxford) died in 1604, for one, and the date of his death is as well documented as you'd expect of any other member of the peerage at that time. That's difficult because 1604 is just after the midpoint of Shakespeare's career, and there are references in several of the plays to events that occurred well after '04 -- the Gunpowder Plot, the Great Frost, and so forth. This doesn't kill the Oxfordian theory, exactly, but it does mean that Oxfordians have to assume from the get-go that more than half of the plays we think of as Shakespeare's underwent extensive and undocumented revision by uncredited dramatists. That, incidentally, is the line most Oxfordians take, though they never bother to explain why some plays didn't undergo revision, or why there aren't mentions of this revised body of plays in pre-1604 sources. Second, Shakespeare's presence as a London author is well-documented. There are of course all the odes to Shakespeare written on his death; Ben Jonson's is probably the most famous. And there are contemporary references to Shakespeare the playwright. Robert Greene's from Groats-worth and Frances Meres' Palladis Tamis are the most famous, but the aggregate of these directly attribute many of the comedies, as well as Hamlet and the histories, to William Shakespeare specifically. And other playwrights criticized Shakespeare's plays pretty frequently, too. Again, Ben Jonson does this most famously with Winter's Tale, when he points out that Shakespeare was apparently unaware that Bohemia was landlocked. Plus, all of Shakespeare's plays published in quarto (about half) and in the First Folio (36 of 38) attribute to Shakespeare as author. So there's that. Anti-Stratfordians, in other words, need to explain why the general public and others working in the theater attributed many of the plays we commonly think of as Shakespeare's to William Shakespeare. This is commonly done using some kind of conspiracy theory, along the lines that De Vere, Queen Elizabeth, or the faked-his-own-death Marlowe was somehow prevented from making his (or her) authorship of Shakespeare's plays public, a conjecture for which I've yet to see any evidence, and which is exceptionally silly for De Vere. His contemporaries knew of him as a playwright -- Francis Meres mentions him as a notable writer of comedies in Palladis Tamia, and attributes to him a different set of works than he attributes to Shakespeare, so it seems clear that Oxford had no clear reason to use Shakespeare as a dramatic mouthpiece as late as 1598 (when Meres dates from). So apart from Oxford's inconvenient death and the widespread attribution of Shakespeare's plays to Shakespeare, there are matters of style. The clearest stylistic difference between Oxford's material and Shakespeare's is that Oxford constantly moralizes -- in that sense he's much more like Spenser, with whom he conferred as an artist and whose poetry he sponsored. The second is that Oxford's language is different from Shakespeare's. Ben Jonson, in his "Ode" famously mentions that Shakespeare had "small Latin and less Greek," which nicely captures Shakespeare's command of any language that wasn't English -- his French and Latin are categorically poor if not nearly incomprehensible. Oxford, on the other hand, was fluent in both. Also, Oxford and Shakespeare wrote in entirely different dialects of English. Oxford was raised in the East Midlands, while Shakespeare was raised in the West. The clearest period dialect distinction between these two areas is the use of the auxiliary "do" in the West, as opposed to the auxiliary "did" in the East -- a choice roughly as distinctive as the "I'll come home soon" in Standard American English and "I'm fixin' to/finna come home" in Southern.* So a West Midlander would write: Fresh winds do shake the darling buds of May While an East Midlander would write: Who first did paint with colours pale thy face? That's a big distinction, and one of the ones used to decide matters of collaboration in Shakespearean texts like Titus Andronicus. Last, and maybe most important, the logic of the Anti-Stratfordian argument has always been a variant of "Shakespeare never went to college, and so could not have written the plays commonly attributed to Shakespeare" -- one reason that Shakespeare's plays are always attributed to well-schooled alternatives rather than, say, Ben Jonson. This is interesting because Ben Jonson never went to college, either. He was a bricklayer's son, went to grammar school in Westminster, and had exactly (as far as anyone can tell, anyway) as many years of education as Shakespeare. And Jonson was the single most popular poet and playwright of his day -- more popular than either Shakespeare or Marlowe, and certianly more than de Vere. More important, Jonson also became England's foremost Classical scholar, and without the formal education the Anti-Stratfordians seem to think necessary to becoming a successful dramatist. So it seems clear that a lack of college education isn't a clear barrier to writing well-crafted, perceptive, and intelligent poetry and plays. I should add that this is the calmest and most well-reasoned response you're likely to get from a Renaissance scholar on the Anti-Stratfordian question, because the Anti-Stratfordian argument somehow manages to live on, despite its support only from the weakest and most tenuous conjectures and its opposition by every single piece of available documentary evidence -- a case of "isn't it possible that all the contemporary printed evidence is wrong about Shakespeare's authorship, but that this entirely unsupported conjecture is right?" You might as well argue that Elizabeth I was actually a man, since all of her portraits could have been misattributed and it's clear she didn't have any children. quote:What do you make of this outfit? And Sasquatch in general? I like cryptozoology as a culture, and I would very much like to think that we live in a world as full of undiscovered creatures that as those creatures are full of awesome. Land sharks with chainsaw teeth. Arboreal polar bears. That kind of thing. But it's sad that there's less evidence for Sasquatch than the Horsham Dragon. At least we've got a body. quote:You read The Cousins Wars? I have not. * Although the American distinction is more tense-complicated.

|

|

|

|

OctaviusBeaver posted:I just started on Julius Caesar, do you have anything I should be looking for or thinking about in particular while reading it? I have already seen it performed so I don't have to worry about spoilers. The thing to keep in mind about JC is that Brutus, rather than Caesar or the other conspirators, is at the center of the play. He's certainly the most well-developed character, and you'll notice that the play begins with his induction into the conspiracy and ends with his death. That's another way of saying that the play's dramatic arc describes Brutus specifically, not the conspiracy or Caesar. quote:One thing that has already confused me is why the other plotters want Brutus on their side so much, the plan to kill Caesar doesn't seem that complicated and Brutus manages to screw it up by not killing Antony, so why include him in the first place? Because it makes the play interesting. One way of thinking about this play is as a meditation on character or reputation (much like 1 Henry IV). Brutus is generally noble, or at least projects a kind of nobility that the other conspirators lack. This is why they need him. Brutus's reputation is what makes Caesar's assassination a meaningful political act rather than opportunistic slaughter. But the needs of Brutus's reputation also make him a terrible conspirator. So you'll notice that once Brutus joins the conspiracy, his opinion is constantly at odds with Cassius's. You'll also notice that, in these conflicts, Cassius is invariably right and Brutus is invariably wrong. Conspiracy is not a job Brutus is built for. So Caesar's assassination has psychic consequences for Brutus, in the same basic ways Duncan's assassination does for Macbeth. The act of murder, in both cases, is pressed on them by outside forces, and their complicity traumatizes them in ways they can't really recover from. That inner conflict -- that failed recovery -- is really what drives both plays. These plays aren't about brilliant political capers. They're about seeing men gradually unwound by inner conflicts that reflect the competing needs of their larger worlds. Put differently, the other conspirators include Brutus for two reasons. In a diagetic sense (that is, by the logic of the play), they include him because they need a spokesman. In a dramatic sense, they need (or the play needs) a deeply conflicted tragic character to make things interesting. Without that, the play's just a series of emotionally weightless interchangeable stabbings.

|

|

|

|

Brainworm posted:Also, Oxford and Shakespeare wrote in entirely different dialects of English. Oxford was raised in the East Midlands, while Shakespeare was raised in the West. The clearest period dialect distinction between these two areas is the use of the auxiliary "do" in the West, as opposed to the auxiliary "did" in the East -- a choice roughly as distinctive as the "I'll come home soon" in Standard American English and "I'm fixin' to/finna come home" in Southern.* This is very interesting. In Modern English, the auxiliary shows tense. How did Eastern English speakers show past tense if their auxiliary was always did? Would they have said things like "I did not ran"? (Same question about Westerners I suppose) I don't know much about the history of English, so if you can point me something to read on this, I'd be much obliged. Or you could just explain it here if you know/feel like it.

|

|

|

|

FoiledAgain posted:This is very interesting. In Modern English, the auxiliary shows tense. How did Eastern English speakers show past tense if their auxiliary was always did? Would they have said things like "I did not ran"? (Same question about Westerners I suppose) I don't know much about the history of English, so if you can point me something to read on this, I'd be much obliged. Or you could just explain it here if you know/feel like it. The auxiliary "do"/"did" actually inflected words meanings in construction-specific ways that weren't always tense related, although for East Midlanders "did" seems to establish something like the imperfective aspect in something like the way "would" does now (and did for West Midlanders like Shakespeare). Anyway. Savvier types (like Londoners) had dropped the auxiliary "do"/"did" construction entirely by the time print culture really took off, and most users of these constructions didn't produce lasting texts (the Midlands weren't home to any printers), so there's a vacuum of evidence and some disagreement. Kokeritz treats the subject briefly in Shakespearean Pronunciation (which needs to be retired), and I'm really only familiar with this issue as it appears in articles that make authorship claims with Shakespeare's auxiliary "do." I'm sure there are major texts on Midlands dialect differences, but I don't know them -- unlike, say, Northerners (with their "ich" and "chill"), East and West Midlanders weren't stereotyped in interesting enough ways to earn stage time. They're outside my ken. But the most common inflections of the auxiliary "do"/"did" seem to go something like this: Winds do shake the darling buds of May = Winds shake buds (emphasis on the relationship between this and other ideas, usually contained in a predicate -- that is, sequences of auxiliary "do" were often used to establish or emphasize parallel structures). Winds shake the darling buds of May = Winds shake buds (emphasis on the general condition of buds and winds). And: I remember, she did paint an inch thick = I remember that she habitually painted an inch thick / "would paint an inch thick" (i.e. imperfective aspect). I remember, she painted an inch thick = I remember a specific instance in which she painted an inch thick. You can see how the functions of the auxiliary "do"/"did" are roughly analogous, in that both draw the listener's or reader's attention to something more general, outside of, or larger than non-auxiliary constructions. What's more interesting is that there doesn't appear to be a usage overlap -- "do"ers were rarely "did"ers, and vice-versa. I should add that, again, there's debate on the precise meanings of the auxiliary "do" especially, and I'm not terribly familiar with every side of it. But I'll see if I can hunt down a good article on the debates surrounding this distinction. Brainworm fucked around with this message at 13:26 on Jun 13, 2009 |

|

|

|

Great thread! I was planning on asking a Cormac McCarthy related question, and was surprised to read a couple pages back that you hadn't read anything of his. Is there any reason behind this, or just plain lack of time? Harold Bloom did call Blood Meridian "clearly the major aesthetic achievement of any living American writer", y'know

|

|

|

|

Gregor Samsa posted:Great thread! Yeah, this is about time. But it's also about reading preferences. I've got no attention span and trend toward early texts, so McCarthy's one of many casualties. But I've got some of the afternoon off, so I'm tracking down a local bookstore to find some Blood Meridian -- I've heard too much about it already, and if I put it off much longer I think I'll lose the novelty of reading it for myself. Also, I get hung up on really good poems. So if I stumble across a "Dover Beach" or "Love in Brooklyn," I can pretty much write off the afternoon.

|

|

|

|

Brainworm posted:Yeah, this is about time. But it's also about reading preferences. I've got no attention span and trend toward early texts, so McCarthy's one of many casualties. But I've got some of the afternoon off, so I'm tracking down a local bookstore to find some Blood Meridian -- I've heard too much about it already, and if I put it off much longer I think I'll lose the novelty of reading it for myself. If you manage to track it down, I'm certainly interested to hear your impression of it.

|

|

|

|

Gregor Samsa posted:If you manage to track it down, I'm certainly interested to hear your impression of it. I'm about halfway through, which is unfortunately as far as I'm going to get in the next couple days. The long and the short of it was that I was thrown by McCarthy's style until I figured out how it works in the text. The most apparent function of this is the atmosphere it lends to the violence. It gives even the most gruesome scenes a weightless quality -- something a less able writer would try to achieve through self-censorship (usually a fade to black, like Norris's "then it became abominable" in McTeague) or some other sweeping omission of detail. In effect, McCarthy's move seems the rough analogue of what Ellis does with the conversational tone of American Psycho, though Ellis doesn't smear so much Vaseline over the lens. But the overall effect is wonderful. There's no self-censorship, exactly. Just a readerly shift in the emotional tenor lent to detailed violence. Like watching a snuff film while you're huffing kerosene.

|

|

|

|

Let's say, for the sake of argument, that you wanted to be the next great writer in history. This century's James Joyce, if you will. What books would you read for study/inspiration? Would you focus on any author in particular or would you take a broad swath of literature from different time periods? Also, this thread is amazing. Thank you for making it!

|

|

|

|

Pardon me if this is a stupid question, but what's the difference between comparative lit and english?

|

|

|

|

Can you give me a hand with this excerpt from Paradise Lost? http://forums.somethingawful.com/showthread.php?noseen=0&threadid=3155525&pagenumber=1

|

|

|

|

Doran Blackdawn posted:Let's say, for the sake of argument, that you wanted to be the next great writer in history. This century's James Joyce, if you will. That's a great question. The more I think about it, the more I think that the issue isn't what an author reads, but how -- and, more important, the more I think that reading skills, rather than writing skills, are what separate great writers from the merely competent and successful. Great writers seem to wrestle with their predecessors. Sometimes, those predecessors are considerably separated: think of how Bret Easton Ellis rewrites Gatsby and Hamlet. Sometimes those predecessors are more immediate: think of how Shakespeare rewrites Marlowe, or how Stephen King rewrites Watership Down in The Stand. Either way, great writers seem to know (either explicitly or intuitively) that the meaning in what they write comes out of tradition as much as it comes out of the words on the page, and so take great care to situate their writings in traditions that give their texts meanings that would, otherwise, remain unavailable. It's the literary version of "standing on the shoulders of giants." Great writers know they work by improving on or reimagining works they find compelling, not by crafting a plot in a vacuum. This doesn't mean their works are derivative. In fact, I think it means exactly the opposite of whatever we'd call derivative, and also exactly the opposite of what we'd call "original," since great writers' readings of others' works seem to be highly idiosyncratic. Ellis, for instance, sees father/son and stepfather/stepson relationships as the center of Hamlet, and so writes his version so that these relationships are foregrounded. The rest of us see Hamlet as a detective story, and so derive Sherlock Holmes, the collected works of Agatha Christie, and CSI. That, in a nutshell, is the difference between Ellis and the other brat pack writers of the 80s, who were competent writers but never strong readers. The same thing's true of King. He sees a sort of heavy-handed fate at the center of Watership Down, and so rewrites that narrative of adventure and displacement in a way that foregrounds those elements in The Stand. Most of us probably read Down as an adventure arising from the interaction of characters with different flaws and virtues, and so derive The A-Team. And that, in a nutshell is the difference between King and the other airport bookstore staples of the 20th century. Clancy and Crichton and Ludlum and Koontz and all the rest are competent writers, but seem to stop reading with their contracts and USA Today. So if I were setting out to be a great writer, I'd seek out the literature that I read differently from everyone else -- that I understand in a possibly unique way not because I bring something to the text that isn't there, but because I bring a perspective that centers something that most other people either miss or only see around the edges. In short, I'd find a text that speaks to me in a different voice, and improve it.

|

|

|

|

xcdude24 posted:Pardon me if this is a stupid question, but what's the difference between comparative lit and english? There are lots of differences, and I'm probably going to miss some big ones. So if any comparative lit people want to pull me out of the fire on this, please do. Basically, English is centered around the study of Anglophone literature, while Comparative Literature is centered around the study of literature from at least two different linguistic traditions; generally, Comparative Literature also takes a cultural studies (rather than formalist) approach to literary interpretation, while English awkwardly balances the two. In practice, this means that Comparative Literature is more heavily interdisciplinary, and that CL departments are generally staffed by faculty from various languages (plus History or regional studies) as well as dedicated practitioners. And it also means that Comparative Literature folks often find homes in English, regional studies, or Languages, since Comparative Literature programs are somewhat rarer than straight-up English.

|

|

|

|

DriveMeCrazy posted:Can you give me a hand with this excerpt from Paradise Lost? Basically, Milton's working with something approximating a Neoplatonic vocabulary for the grandeur of God, and in the process unfolding a causal paradox at the center of that grandeur -- something amounting to a blanket statement that language can approach the nature of the divine only at a slant, and then still awkwardly. This paradox is laid out in the opening couplet. Light is the first of God's creations, but also synonymous with God. This seems like a causal contradiction, but Milton "resolves" that in his third and following lines. He expects the reader to see the contradiction, but then says "May I express thee unblam'd?" -- both meaning that God/Light is "unblamed" (and hence different from the post-lapsarian narrator), and (consequently) that the narrator cannot "express" God/Light's nature in a fitting manner -- the act is itself deserving of "blame" for pretending to represent a glory beyond language. Lines 4-6 dilate this paradox, and culminate in the terminal "increate," a word Milton coins here to approximate the way God can both "be" light and "create" light. One form of light, the "God is light" kind, has always dwelt in God, and is consequently eternal and synonymous with Him. The second kind -- the "bright effluence" -- is the "created" light, a sort of constant consequence of the first kind, not really "created" because it's not exactly new, but not really eternal because it wasn't always there in exactly the same way. Hence, the light is "increated," or made new without being made from nothing. The important things to keep in mind about this passage are (1) that Milton is tossing out a disclaimer about his handling of God: Anything I say that looks like a contradiction is basically a consequence of post-lapsarian language's inability to capture Truth; and (2) that line 3 meets a response Milton assumes the reader has had to lines 1-2. This is arguably the logic of Paradise Lost as an entire text.

|

|

|

|

Brainworm posted:That's a great question. The more I think about it, the more I think that the issue isn't what an author reads, but how -- and, more important, the more I think that reading skills, rather than writing skills, are what separate great writers from the merely competent and successful. Piggybacking off this, what do you think the best way to improve your reading skills would be? Obviously, to read more books I would assume, but what else? Before you mentioned the books, How to Read a Book, How to Read and Why, and The Western Canon. Would anything else be beneficial to add to that pile? Thanks again for your reply - it was very informative! what are you talking about i dont want to be a writer ceaselessfuture fucked around with this message at 15:46 on Jun 21, 2009 |

|

|

|

Doran Blackdawn posted:Let's say, for the sake of argument, that you wanted to be the next great writer in history. This century's James Joyce, if you will. Doran Blackdawn posted:what are you talking about i dont want to be a writer Repeat after me: I AM NOT JAMES JOYCE I AM NOT JAMES JOYCE I AM NOT JAMES JOYCE Brainworm: thanks for the advice on the wall of shame. I'll respond/probably ask more questions later in the summer when I'm fixing up my syllabus for real real

|

|

|

|

Doran Blackdawn posted:Piggybacking off this, what do you think the best way to improve your reading skills would be? Obviously, to read more books I would assume, but what else? Yeah -- I can see that I misread your original question a bit. So let me try to (re)answer both. Literature is at least as much about tradition as it is about words on the page, and this is especially true for more durable and intricate forms of writing (like sonnets). But even with relatively recent forms like the novel, tradition matters tremendously. So improving your reading skills is partly about understanding the words on the page, and there are lots of sources that help do this well. How to Read a Book is a good example, as are any of a million companions to reading specific forms, such as Mary Oliver's Poetry Handbook or David Ball's Backwards and Forwards. But improving reading is also about understanding tradition. Without tradition, words don't really mean anything. You can't understand a sonnet like Teasdale's "Broadway" or Yeats's "Leda and the Swan" without knowing that sonnets are always love poems. It's just a part of the form, and those poems rely on that form in order to make their meaning. You can probably guess where I'm going with this: being a better reader means reading more, but it specifically means reading more poetry. Poetry makes you pay attention, and give you the strength to sustain attention. It's like squats for your brain. The problem that most people seem to run into with their poetry readings is that they get caught up in taxonomy. "That's a metaphor," they say, or "that's a response to anxieties about European colonialism." Those can be useful observations, but only if they let you operate on the text. Otherwise, you're just naming parts. You're like an ER doc who says "I think you mean your tibia is broken. Actually we call that a greenstick fracture," and moves on to his next patient. So let's take a look at a simple poem. This is one of my favorites, actually: Wakeman's "Love in Brooklyn." John Wakeman posted:"I love you, Horowitz," he said, and blew his nose. We could talk all day about what the meter in this poem does. It's basically iambic pentameter in the same ways that most poems are iambic pentameter -- lots of lines start with spondees, and Wakeman breaks meter when he wants you to pay attention to something, like that tank sliding through the trees. And of course that tank is a simile, the only one in the poem. And it's also easy to notice that this is a sort of variation on the English sonnet, since we've got three stanzas followed by a unit that takes the poem in a different direction. But those things only matter if they help you read the poem's dramatic situation -- that is, understand what these two characters are all about. They're loud and drunk and brassy, but they're still capable of a touching sincerity (this is Brooklyn, after all, and before it turned into a hipster kiln). And the guy has that sort of live-wire energy and fragility that really only come with romantic risk, so he's crushed when Horowitz doesn't appreciate -- or doesn't appear to appreciate -- the gravity of what he's said. Lucky for him, she's nice. Otherwise this poem ends five martinis later with him slitting his wrists in a bathroom stall. Now if you can see those things in the poem, then a naming of parts is probably going to get you someplace. At that point, it's useful to talk about meter, or about how Wakeman's sort of gestured toward the sonnet form with this poem that, at first glance, looks nothing like a sonnet. That point, in other words, is where you start talking about how the poem works, rather than what it does. Point is, this second step not nearly as important as the first, and while it's nice, I'm not sure it helps make you a better reader unless you're already pretty good. So poetry, poetry, poetry. It's great for helping you see what's going on in a text even when you're given minimal clues. But with the exception of Skelton and Wyatt, I'm not sure anything earlier than Shakespeare is worth much of your time. Reading drama also helps, and for the same basic reasons. A play is really just a skeleton (as opposed to a novel, which is sort of a whole body). Actors and directors bring the vital organs and the muscles. So plays have a great deal more interpretive leeway than novels generally do, which is great exercise for you as a reader -- you need to constantly empathize with the text in order for it to make sense, e.g. ask "how does this guy feel about this, and how does he act because of it?" Novels generally tell you, but the interesting ones make you guess. And the better guesser you are, the more you're going to enjoy it. So with drama, again, I'm not sure there's much worth reading before Shakespeare (except Marlowe). But I'm also tempted to say that there's not much worth reading between Shakespeare and the 20th century -- My American Cousin and Ideal Husband are clever, but not really good training for subtlety. I love Oscar Wilde, but I don't think anyone's ever been inspired by him. And when it comes to tradition and novels, the science is deciding what to read next. I like to read whatever shows up in in the text of whatever I'm reading, since when authors rewrite someone else's work, they generally let you know it. To follow up on those earlier examples, King spends a good deal of time in The Stand talking about Watership Down, and not in a way that has anything to do with the actual plot. It's the only book Stu Redman ever mentions reading, and he remembers reading it at some length -- longer than he thinks about his first wife, even. And it's also the only book any of the other principal characters appear to have read, too. So that kind of thing is a clue. King cut however many hundreds of pages out of Stand, but he thought that bit on a kids' book about rabbits important enough to leave in, which means that King thinks that Down has a great deal to do with the story he's telling. That in turn means that Stand and Down are probably useful reading in tandem. So apart from what I mentioned way at the top, I don't have much criticism for you. But I can recommend reading poetry, drama, and novel pairings, since those all develop whatever senses you have for subtlety and tradition.

|

|

|

|

Defenestration posted:Becoming a better reader is a fine goal, and so is becoming a better writer, but I sense something dangerous here. So I'm going to do for you what a very famous writer did for one of my professors (and thus saved his career) Don't worry, I'm not nearly that egotistical or anything, I was seriously looking to keep my question purely hypothetical! I have no illusions of James Joyce or Best Writer Ever or anything. Just figured to give some direction to the question I guess. quote:Yeah -- I can see that I misread your original question a bit. So let me try to (re)answer both. Actually, you gave me the exact answer I needed to know, but didn't realize yet. Thanks again for both replies; you've given me much to think on!

ceaselessfuture fucked around with this message at 18:36 on Jun 21, 2009 |

|

|

|

Somehow this thread fell off my bookmarked threads list! I have a lot of catch-up reading to do. Related to these last few questions, though, how might one go about becoming a faster reading? Or is reading/practice the only way?

|

|

|

|

I've read every post in this thread I'd like to thank you for taking the time to provide such a great resource. I'm a history-politics undergraduate at a UK university but seeing things from a professor's perspective and reading what is expected of students has really helped improve my understanding of what I should be doing in my work. I've got two unrelated questions: 1. I want to get into Shakespeare and because of my workload I've decided to do it by watching films of his plays. I'm a complete Shakespeare newbie so which plays do you recommend I watch first? Say five or six for starters and the versions you recommend. Is there also a companion book that I could read to help me understand what exactly happened? For example — I watched Laurence Olivier's Richard III recently and enjoyed reading the Wikipedia page afterwards to understand what really happened and some of the issues the play examined/created. 2. Have you always been able to read so fast or is it something that you developed? I'm picking up on a post where you said that you can read 300 pages of a regular book in an hour and 150 pages of an academic book in the same time. I could really do with improving my reading speed but without dropping my comprehension ability. Do you have any suggestions beyond practice? As a thanks for your time here's Peter Sellars performing The Beatle's 'Hard Day's Night' in the style of Olivier's Richard III: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLongUBPm5Y

|

|

|

|

Fast Moving Turtle posted:Somehow this thread fell off my bookmarked threads list! I have a lot of catch-up reading to do. Related to these last few questions, though, how might one go about becoming a faster reading? Or is reading/practice the only way? Umbriago posted:Have you always been able to read so fast or is it something that you developed? I'm picking up on a post where you said that you can read 300 pages of a regular book in an hour and 150 pages of an academic book in the same time. I could really do with improving my reading speed but without dropping my comprehension ability. Do you have any suggestions beyond practice? There were a few moments I noticed big improvements in my casual reading speed. The first is when I stopped subvocalizing -- that is, stopped reading aloud to myself in my own head, if that makes sense. Subvocalizing can be fun, like when you decide to listen to anything by, say, Baudrillard in the voice of Skeletor. But it's not necessary for comprehension, and I think it may actually be counterproductive. So the first lesson, if that's what you want to call it, is to push your reading speed past what the narrative voice in your head is comfortable with, and check your comprehension at the end of each chapter, section, or episode by summarizing what just happened in your own words. The second thing that helped was holding the book further away. Seriously. All other things being equal, I can comfortably read nearly twice as quickly when I hold a book at almost arm's length. This isn't a vision issue, or doesn't seem likely to be one, since students I work with report similar improvements. I think it may have more to do with how your eye parses words as groups or lines, but I dunno. Anyway, it seems to work well for people who aren't me. The third thing that helped was tracking my progress on the page with my hand. I don't think this helps tracking as much as it helps me keep a quick and steady pace through my reading, and keeps me from distracting myself. Last, I started reading some texts (like academic ones) recursively, rather than linearly. That is, I move through the text in its entirety without stopping to puzzle over difficult or complex sentences or ideas -- I just flag the pages they appear on. Then, when I reach the end of the chapter or section, I go back and look at what I've flagged. More often than not, the confusion's been cleared up by something written later on. That way, I don't burn time deciphering something stated more clearly on following pages. So those four things seem like good starting points. The only other thing I have to add is that reading a complex text quickly requires your entire attention. I've heard people swear up and down that they read better with e.g. background music, but a few short studies I ran with some Rhet/Comp folks put the lie to this claim -- it's probably better phrased "reading is more tolerable when there's something else going on, so I'm more likely not to drop my reading out of boredom if I can fantasize about Avril Lavigne." I'm just as bad about this as anyone else, especially when I'm grading papers. But one thing I learned when I was working as an AP reader is how quickly and well I can grade if I just concentrate on it to the exclusion of anything else. So give these a shot and see what happens. I'll be interested in hearing what they get you.

|

|

|

|

Would you mind going into more detail in regards to stopping subvocalization? It may just be that it's so inextricably tied up in my thought processes that I can't imagine reading without it, but... well, I very literally can't imagine reading without it. If I don't subvocalize, it seems that I'm simply moving my eyes across the page with no comprehension whatsoever because I have no limit to my speed. In other words, it seems that if I don't subvocalize, I still move my eyes across the lines, but far too rapidly to garner any sort of understanding.

|

|

|

|

Umbriago posted:I want to get into Shakespeare and because of my workload I've decided to do it by watching films of his plays. I'm a complete Shakespeare newbie so which plays do you recommend I watch first? Say five or six for starters and the versions you recommend. Is there also a companion book that I could read to help me understand what exactly happened? For example — I watched Laurence Olivier's Richard III recently and enjoyed reading the Wikipedia page afterwards to understand what really happened and some of the issues the play examined/created. There's a nice anthology creatively titled Shakespeare and Film that should give you most of the companion reading you need. And there's also a fantastic DVD series, Playing Shakespeare, that more or less follows the complete BBC productions from the early 80s. Both are excellent companions. But as far as watching the films goes, I'd try to see a few different versions of each. And I'd also consider going to one of your local Shakespeare festivals, if you're lucky enough to have one. Summer's generally the season for these. And I'd start with seeing the seven major tragedies, since these are (with the possible exception of Midsummer) the most often put to film, so you've got lots of versions to choose from. But whatever you do filmwise, I'd always include the BBC productions. That's a fabulous group of actors, and though the films are a bit dated they've generally aged well. quote:As a thanks for your time here's Peter Sellars performing The Beatle's 'Hard Day's Night' in the style of Olivier's Richard III: This is nice. I've always found Olivier endlessly imitatable. Not that there's a great population of folks ready to hear an Olivier impression.

|

|

|

|

Jumping back a few pages, you mentioned Kurt Vonnegut and how you expect him to be common in literature courses in the future. I would definitely agree with you there. Vonnegut has one of the most unique and beautiful writing voices that I've encountered, and ever since reading Slaughterhouse 5 my freshman year of high school, I've wished we could discuss him in class instead of, say, Great Expectations. I've actually been toying with the idea of designing a student-taught class for next spring, but I don't think I'm qualified on the literary analysis side of things (philosophy major)- I'd need to convince an English major friend to help me out. Since your quick analyses of other works in this thread have been fascinating, do you think you could write something up about Vonnegut (in general, or about one or two novels)? I'd be particularly interested in hearing about Breakfast of Champions or Cat's Cradle, two of my favorites, but do whatever suits you. What's your opinion of his short stories? They seem to be of very mixed quality- a few (Harrison Bergeron, to name one) are almost too good to describe, but others feel soulless or trite. Also, this thread is fantastic. It's making me regret not utilizing my school's English department more.

|

|

|

|

Fast Moving Turtle posted:Would you mind going into more detail in regards to stopping subvocalization? It may just be that it's so inextricably tied up in my thought processes that I can't imagine reading without it, but... well, I very literally can't imagine reading without it. If I don't subvocalize, it seems that I'm simply moving my eyes across the page with no comprehension whatsoever because I have no limit to my speed. In other words, it seems that if I don't subvocalize, I still move my eyes across the lines, but far too rapidly to garner any sort of understanding. I got more comfortable reading without subvocalizing by quickly passing my eyes over a sentence, closing them, and reciting the sentence from memory. And what finally convinced me that I was doing something right was that I had slightly better recall without subvocalizing than with, even though non-subvocalized reading felt a bit unnatural. So give that a shot and see if it helps.

|

|

|

|

Handsome Rob posted:[...] do you think you could write something up about Vonnegut (in general, or about one or two novels)? I'd be particularly interested in hearing about Breakfast of Champions or Cat's Cradle, two of my favorites, but do whatever suits you. What's your opinion of his short stories? They seem to be of very mixed quality- a few (Harrison Bergeron, to name one) are almost too good to describe, but others feel soulless or trite. The Short Stories In brief, I agree with you entirely about them. If you look at Vonnegut's arsenal as a writer, almost all his best tools (refrains, accretion of structural ironies) don't work in the short story form. There just isn't space. And Vonnegut is remarkable for the emotional complexity he brings to his work through the iteration of simple ideas which, again, is out of bounds for a short story. The overall effect is that Vonnegut's short stories sound like they were written by a completely different person. There isn't really any complexity -- the closest you get is a sort of heavy-handed political or social allegory. Which is a shame. The thing that makes Vonnegut a fantastic novelist is that he admits to remarkable political, social, and emotional complexity. So most of his short stories read like typical pulp science-fiction shorts, because that's exactly what they are. The upshot is that even Vonnegut's best short stories seem trite when up against even the worst of his novels. I mean, slap a drum solo in the middle of "Harrison Bergeron" and you'd swear it was written by Geddy Lee. The Novels The thing to keep in mind about Vonnegut is that he made a career of re-writing canonical pieces of American fiction -- generally, but not always, fiction of the 19th century. And you can talk about almost every element of his novels (excepting Player Piano) in exactly those terms. The best and clearest example is Slaughterhouse Five, which is basically Red Badge of Courage turned inside out.* And neatly. Every superficial comparison you can make between the two books is almost exactly on. Badge features Henry Fleming, mostly referred to as "the Youth," while of course the subtitle for Slaughterhouse Five is The Children's Crusade. Stephen Crane never had any direct experience of combat or even violence -- he was born long after the Civil War ended -- so Vonnegut deliberately leads his book with a claim to exactly the opposite effect. He was in Dresden when it was firebombed, and Slaughterhouse Five begins with a series of direct narrative claims about the relationships between his wartime experiences, postwar reflections, and his writing. And the list goes on. Henry Fleming's wounds are (a) physical and (b) fraudulent but meaningful, while Billy Pilgrim's are (a) psychological and (b) legitimate but pointless. And you'll also notice that Slaughterhouse doesn't have any blood. All the dead bodies are either burned to a crisp or marbled blue and white** -- the so-called "red badge of courage" is deliberately avoided. And of course Vonnegut deliberately perverts the narrative arc of Badge; instead of Fleming's progress from cowardice to bravery, you get Pilgrim's progress from fragility to insanity. And of course these are meant to parallel one another. Get it? These are all simple observations. High-school level, really. But this is because Vonnegut wants you to see the parallels. They're the point. Without a canonical American war novel, Slaughterhouse Five is a pointless book. It needs Badge specifically, or, more generally, an American eheu fugaces tradition to work against in order to mean anything. And the book tells you this over and over and over again. Think about when Pilgrim watches that war movie go in reverse; the reversal is only meaningful because it's in opposing dialogue with the original. You wouldn't get the same effect if Pilgrim watched, say, a generally pacifist film. But more to the point, that's one of a bunch of places Vonnegut makes implicit claims about how he's rewriting the American war novel. He's hardly subtle there. And you can run the same play with Vonnegut's style. You'll notice that Player Piano reads absolutely nothing like Slaughterhouse and Vonnegut's post-Slaughterhouse novels, because the style in Slaughterhouse is deliberately opposite Stephen Crane's, which is basically picturesque American Realism -- think detailed photographs made from complex and thickly layered sentences. Vonnegut is, consequently, deliberately staccato, surreal, and generally non-realist. He does everything he can to avoid detail. And he runs with that style for the rest of his career. So, as a rule, this is how I understand Vonnegut: a skilled and deliberate inverter of Crane, Alger, Melville, and the rest of the American Realist canon. And that's where he hits his stride. The moments where he's not running this play are his weakest, far and away. The short stories are generally in this category, along with Player Piano and whatever other pre-Slaughterhouse texts you can dig up. * I should add that this assessment of Vonnegut is completely my own. If you bring it to an American Lit class, they'll think you're eating peyote. But you'll be able to convince them you're right, because I'm right. Because I'm awesome. ** And OH MY GOD when you put them together you get red, white, and blue.

|

|

|

|

Loved that analysis! I take it you'd say Breakfast of Champions and God Bless You, Mr Rosewater are his take on Alger?

|

|

|

|

Brainworm posted:I got more comfortable reading without subvocalizing by quickly passing my eyes over a sentence, closing them, and reciting the sentence from memory. And what finally convinced me that I was doing something right was that I had slightly better recall without subvocalizing than with, even though non-subvocalized reading felt a bit unnatural.

|

|

|

|

PrinceofLowLight posted:Loved that analysis! I take it you'd say Breakfast of Champions and God Bless You, Mr Rosewater are his take on Alger? Certainly Breakfast is, and it seems clear that Rosewater draws on the Alger worldview, though there might be a clearer antecedent text. Either way, I haven't read enough Alger to make a good case for point-by-point correspondence between any of the sets of texts, but it seems really clear that Breakfast is meant as a sequel-style response to Alger's story formula, which generally ends with promotion and marriage.

|

|

|

|

Which editions do you like? I'm teaching Titus Andronicus next semester in an intro to English lit class, and wasn't particularly impressed with the Oxford edition that I used last time. Editions need to be cheap and accessible for my students.

|

|

|

|

ma i married a tuna posted:Which editions do you like? I'm teaching Titus Andronicus next semester in an intro to English lit class, and wasn't particularly impressed with the Oxford edition that I used last time. Editions need to be cheap and accessible for my students. For single texts, I like the Folgers. They're generally well edited, though aimed at general readers (which is probably what you want for an Intro class anyway). More important, they do facing-page text notes (rather than footnotes or endnotes) which in practice means that there's tons of notetaking space in the book. They do both mass market and trade paperback editions, and the MMs still run about six bucks and are widely available used.

|

|

|

|

That edition looks pretty much exactly right, thanks.

|

|

|

|

Brainworm, this may be a little off-topic, but do you have any tips for reading retention? I'm the type of person who remembers particular characters/scenes/plot points that stick out to me, but sometimes even the overall narrative of a book or play will be lost to me after a while.

|

|

|

|

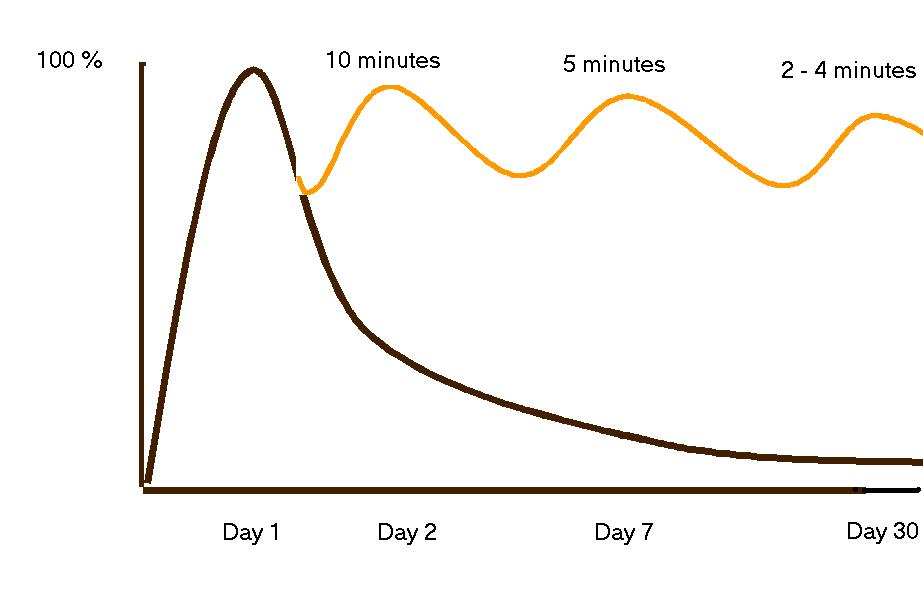

Ayatollah Metroid posted:Brainworm, this may be a little off-topic, but do you have any tips for reading retention? I'm the type of person who remembers particular characters/scenes/plot points that stick out to me, but sometimes even the overall narrative of a book or play will be lost to me after a while. No problem. This has been an area of study since the late 19th century, when Hermann Ebbinghaus published Über das Gedächtnis. That study first postulated that forgetting is best described exponentially, by R = e^-[t/s], where R is retained information, s is a bizarre memory-specific variable describing the strength or vividness of an event when it is experienced, and t is time. Ebbinghaus's derivatives and follow ups suggest that the retention of information is improved by spaced repetition -- this is probably familiar to you if you've ever used any type of graduated-interval recall methods like Pimsleur (which has review intervals at 5 seconds, 25s, 2 minutes, 10m, 1 hour, 5h, 1 day, 5d, 25d, 120d, and 2 years). It's most frequently used to teach languages, but is fantastic for e.g. flashcards or students' names. For less "instantaneous" information, like a novel plot, you want to follow a review schedule described by the so-called "Curve of Forgetting," which looks like this:  That is, you'll want to review what you've read for about ten minutes the day after, about five minutes one week after, and then another few minutes at one month, six months, and two years. For novel and play plots, characters, etc., I spend my ten minutes the day after writing everything I want to remember on an index card that I keep in the book, and then (re)read the card a few times for my reviews. Also, Google Calendar is a fantastic tool for keeping your review schedule straight; I've been doing this for something over fifteen years, and one hour a week for the five-minute reviews has always been plenty of time.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 10, 2024 08:01 |

|

Sorry if this has already been asked: What's the deal with minimum page requirements for undergrad assignments? It's something that's always irked me. The business world has an emphasis on clear and concise communication. I have yet to be handed back a report and be told "you made some good points, could you add 5 pages?" So why is the requirement put in place?

|

|

|