|

Tomn posted:Speaking of which, how often were catapults and siege weapons in general used in pre-gunpowder naval warfare and how effective were they? I imagine that a big ol' rock falling on top of a galley would do a ton of damage, but accuracy would be a major issue. Ballistae seem like they'd be more accurate, but if even cannons have problems sinking wooden ships it seems like giant crossbows are more useful in anti-personnel than actually trying to damage the ship. From what I've read, they weren't very common, and they weren't effective in sinking ships, but could be useful in killing rowers and marines. When warmachines were used on galleys, the galleys already had decks, so sinking them with catapults would have required massive stones.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 8, 2024 18:18 |

|

Hogge Wild posted:From what I've read, they weren't very common, and they weren't effective in sinking ships, but could be useful in killing rowers and marines. When warmachines were used on galleys, the galleys already had decks, so sinking them with catapults would have required massive stones. Don't forget the fact that carting a bunch of massive stones around is a great way to overload and sink your own ship.

|

|

|

|

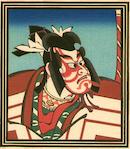

Ceramic Shot posted:What's the deal with medieval naval combat? From what I've been reading, there was not much innovation from the fifth to fifteenth centuries in terms of strategy and tactics, but that seems really dismissive and hard to believe. Even though there were innovations in construction (clinker style construction of longships?) it seems like this period was even more straightforward than in ancient times, where shooting, rams, and boarding were all present. Tomn posted:Speaking of which, how often were catapults and siege weapons in general used in pre-gunpowder naval warfare and how effective were they? I imagine that a big ol' rock falling on top of a galley would do a ton of damage, but accuracy would be a major issue. Ballistae seem like they'd be more accurate, but if even cannons have problems sinking wooden ships it seems like giant crossbows are more useful in anti-personnel than actually trying to damage the ship. I'm getting most of this from War at Sea in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: Ballistae are a well-documented part of Byzantine naval combat, and were used mostly to clear crew before hand-to-hand boarding could seize the ship. These would shoot arrows or small rocks to complement other on-board archers; naval combat often had a distinct "missile phase" and "melee phase", and the prominence of one or the other depends on the force. Medieval Genoan and Iberian/Spanish navies, for instance, heavily emphasized the missile phase and would design ships with high bulwarks or towers to aid in shooting. This was because those forces had access to a large amount of professional crossbowmen. Naval combat in Northern Europe, which we lack sources on but whatever, would tend towards the opposite with lower-set designs for maneuverability. A mix of the two is present in most cases. Boarding itself is usually accomplished by grappling poles to pull the ships towards each other (or push them away, if you're being attacked). The larger siege engines aren't nearly as prevalent. Keep in mind that siege engineering is not exactly common knowledge, stone-throwing engines would need very large ships to support them, and they'd be quite inaccurate in any case. But it's clearly possible. Huge rock throwing catapults are distinctly depicted in Chinese warships. That image dates from ~the 12th century, and shows a counterweight trebuchet; man-powered traction trebuchets would have been present even earlier. Chinese naval combat could support this because it tended to take place on stable rivers or lakes that supported huge, multi-decked, flat-bottomed boats. That's just not possible on the ocean or the Mediterranean. We don't see European naval artillery being too decisive until the invention of cannon.

|

|

|

|

Since there we spoke about katanas: it's 2015 and high time that the cool guy/girl survivor in the zombie genre be a longsword wielding machine of death. It's not the 90s amymore.

|

|

|

|

Grand Prize Winner posted:I saw your comment before reading the link and just assumed you were talking about one of your dudes.

|

|

|

|

JaucheCharly posted:Since there we spoke about katanas: it's 2015 and high time that the cool guy/girl survivor in the zombie genre be a longsword wielding machine of death. It's not the 90s amymore. A rapier would be perfect for this.

|

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:if it's 1631 and another mercenary insults you, you really have only two options if you want to keep respecting yourself. the first is fight him (you might get hurt too), the second is take him to court and get a verdict that you are, in fact, an honorable person. So if the verdict goes against you and doesn't say you're honorable, do you default to fighting? That'd probably lend a certain degree of practicality to the judges.

|

|

|

|

Tomn posted:So if the verdict goes against you and doesn't say you're honorable, do you default to fighting? most of the time, the verdict is in favor of the injured party, because you can't just go around calling someone names in public, they are civilized people

|

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:i have only seen that happen once, where a guy called another officer a horse thief and it turned out that he actually was one Goddamn, YouTube comments would give your guys an aneurysm. So what happened to the horse thief dude?

|

|

|

|

Tomn posted:Goddamn, YouTube comments would give your guys an aneurysm. he got arrested

|

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:if it's 1631 and another mercenary insults you, you really have only two options if you want to keep respecting yourself. the first is fight him (you might get hurt too), the second is take him to court and get a verdict that you are, in fact, an honorable person. At this point are these types of honor-duels legally sanctioned or completely extra-legal? I was always impressed by Davis' sources in Fiction in the Archives because through the possibility of royal pardons they drag extra-judicial killings (often justified in pardon requests as responses to injured honor) into the legal system and the realm of legal discourse. Is there a similar dynamic in 17th-century Germany? Davis' pardon requests seem to depend heavily on contemporary understanding of the French king's authority and legal role.

|

|

|

|

deadking posted:At this point are these types of honor-duels legally sanctioned or completely extra-legal? I was always impressed by Davis' sources in Fiction in the Archives because through the possibility of royal pardons they drag extra-judicial killings (often justified in pardon requests as responses to injured honor) into the legal system and the realm of legal discourse. Is there a similar dynamic in 17th-century Germany? Davis' pardon requests seem to depend heavily on contemporary understanding of the French king's authority and legal role. So You've Just Killed A Guy In A Duel Was it self defense? If yes, and you can prove it, you walk Did he try to take your sword, which nobody may do since it is "that by which you receive money from the lords" and also "for defending your life"? If yes and you can prove it, you walk Did you draw first/keep fighting after he ran/something else that means it wasn't self defense? If yes, you'll probably get condemned to death by a military tribunal Can you appeal? To whom? Yes. Either to your oberst, your oberst lieutenant, or...I think the highest local authority that employs you, so a lot of guys have their cases reviewed by the Elector of Saxony but Mansfeld Regiment cases get kicked upstairs to the Governor of Milan, not the King of Spain even though they "serve the King of Spain." And then what? You stand a good chance of getting pardoned. So I think it's similar but you don't have the same discourse about what the king can and can't do because this is an Empire, not a kingdom, and because mercenary regiments/free companies are also legal entities. It's not completely extra-legal, but the regimental authorities would really prefer if these guys didn't kill one another all the time. HEY GUNS fucked around with this message at 20:34 on Nov 23, 2015 |

|

|

|

How much effort was it to prove you were acting in self-defence? Many historical fighting manuals have big sections of nonlethal solutions for armed encounters, which have always felt a bit out of place to me. I suppose they would make more sense if I could get my head around the idea that stabbing people in the face just wasn't cricket in most situations even back in the early modern period.

|

|

|

|

Siivola posted:How much effort was it to prove you were acting in self-defence? Many historical fighting manuals have big sections of nonlethal solutions for armed encounters, which have always felt a bit out of place to me. I suppose they would make more sense if I could get my head around the idea that stabbing people in the face just wasn't cricket in most situations even back in the early modern period. These guys don't really try for nonlethal hits. Oh, you can hit a guy with a cleaver or a piece of wood or a big thing of leather and he'll be fine, but once the swords come out they intend to kill. HEY GUNS fucked around with this message at 22:02 on Nov 23, 2015 |

|

|

|

I have a question that others may know more about than me. On occasion I have read that most men-at-arms were not knights, and that this was often by choice – the men-at-arms in question did not want the extra responsibilities or expenses of a knight – particularly in later centuries or in England. In that case, what were those responsibilities or expenses required of a knight but not from an unknighted man-at-arms? Presumably a professional warrior would want to equip himself for battle the same way regardless of whether he was knighted or unknighted. Similarly, I have seen medieval price lists suggest a knight would be paid double what a man-at-arms is paid. Or scholagladiatoria occasionally suggests in his videos that only knighted knights were allowed to wear swords in town. So there were presumably some benefits to a knighthood as well. Essentially, anything you can tell me about the pros and cons of knighthood (versus the same guy remaining an esquire or unknighted man-at-arms) please. General time-frame I am thinking of is 1400-1550, but other time periods are welcome, and I am ideally looking for things outside of England and more towards Central Europe, although answers from England are welcome too. Thanks in advance!

|

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:he got arrested Was horse theft a capital offense? Also, if you called a honourable man unhonourable, how much was the fine?

|

|

|

|

Railtus posted:I have a question that others may know more about than me. On occasion I have read that most men-at-arms were not knights, and that this was often by choice – the men-at-arms in question did not want the extra responsibilities or expenses of a knight – particularly in later centuries or in England. Hey! Finally something I kinda know! So my frame of reference is France in the HYW-which may or may not be relevant to your question-but my understanding is that the rank of knighthood carried military obligation to the crown of a certain number of days per year. This service could be waived in exchange for a fee, so there may have been a kind of financial balancing act between the promise of a good wage versus the expense of paying to avoid service. Keep in mind that a proto middle class of new men is starting to rise (from the cities but encroaching into the country)and they may not have wanted to enter into knighthood, either because of a prejudice against the lower nobility who were their habitual rivals, or out of loyalty to their own class identity/way of life. That last bit is semi-educated speculation. I don't know too much about the social benefits of knighthood in terms of day to day lived experience, unfortunately. I do know that knighthood specifically required the maintennance of one's own weapons and armor in addition to a small retinue, unmnighted men at arms had lower standards to uphold and could even be provided for by someone higher in the military hierarchy.

|

|

|

|

VoteTedJameson posted:Hey! Finally something I kinda know! So my frame of reference is France in the HYW-which may or may not be relevant to your question-but my understanding is that the rank of knighthood carried military obligation to the crown of a certain number of days per year. This service could be waived in exchange for a fee, so there may have been a kind of financial balancing act between the promise of a good wage versus the expense of paying to avoid service. Keep in mind that a proto middle class of new men is starting to rise (from the cities but encroaching into the country)and they may not have wanted to enter into knighthood, either because of a prejudice against the lower nobility who were their habitual rivals, or out of loyalty to their own class identity/way of life. That last bit is semi-educated speculation. That actually makes a lot of sense: those however-many-days of required military service/campaigning could easily become very expensive, both from the costs of being on campaign and loss of income. Whereas the unknighted man-at-arms could essentially join the same campaign and the wage paid to him means he is not out-of-pocket for going to war. Thanks for that insight! Is there any more you can say about the obligations surrounding maintenance of equipment (which I would expect a man-at-arms to do) or the retinue requirement? Are there recorded examples of Sir X is required to provide Y troops that seem like a regular obligation rather than a one-off command?

|

|

|

|

I recently ran across an interesting article in on pretty much this topic. It doesn't go deep into details, but you might be interested anyway. Honour and Fighting – Social Advancement in the Early Modern Age

|

|

|

|

Railtus posted:Is there any more you can say about the obligations surrounding maintenance of equipment (which I would expect a man-at-arms to do) or the retinue requirement? Are there recorded examples of Sir X is required to provide Y troops that seem like a regular obligation rather than a one-off command? Yes, although it's a little hard to decode. So, the vocabulary surrounding professional soldiers varies wildly over time and can even be internally contradictory. But I have it here that as of 1445 in France, Charles VII instituted a new universal standard of organizing/equipping an army. The army was divided into groupings called 'lances' which consisted of a knight, his sword-bearer (squire, presumably), page, two archers and a varlet- a term which I can't find adequately defined anywhere. It might be another person of squire rank, serving in different duties. So the 'lance' system of organization had been in effect for a long time but as I recall, one 'lance' used to be three men at arms- a knight and his two squires. Mind you, these requirements fluctuate over time due to the demands of war, the availability of nobles (the Piague in 1381 and Agincourt in 1415 are serious impediments) and the ability of the crown to extract minor nobility's military contributions. The reason that the knight is required to bring archers (probably meaning crossbowmen in context) is that this arrangement comes from Charles VII's "grande compagnies d'ordonnance"- meaning that for the first time, feudal obligation is being applied toward making a cohesive and balanced army. An interesting factor to consider also, is that the old feudal obligations actually stand- the king of France had the (theoretical) right to summon ALL nobility to war (a right called the 'ban', with a back-up measure called the 'arriere ban' and a third extra-backup called the 'semonce apres bataille' made to recoup losses from a defeat) but by the 1400s, this right was considered outdated and pretty much never invoked. Instead, it was expected that the king (or duke or count, whoever was organizing the war effort in question) would engage nobility in contracts of military service, not simply summon them. Everyone keep in mind, I'm actually an anthropologist not a historian or medievalist, so this is all just coming from an amateur with access to an academic library. Please feel free to set me straight, anyone who knows better.

|

|

|

|

deadking posted:At this point are these types of honor-duels legally sanctioned or completely extra-legal? I was always impressed by Davis' sources in Fiction in the Archives because through the possibility of royal pardons they drag extra-judicial killings (often justified in pardon requests as responses to injured honor) into the legal system and the realm of legal discourse. Is there a similar dynamic in 17th-century Germany? Davis' pardon requests seem to depend heavily on contemporary understanding of the French king's authority and legal role. In England at this point, duels are completely unsanctioned. And you'd be fairly reckless to hope for a royal pardon. Elizabeth was known to execute people for marrying the wrong woman, let along killing someone, and James hated dueling. In fact, during Jame's reign just reporting that a duel had taken place could get you hauled up in front of Star Chamber. That didn't mean that a high ranking aristocrat probably couldn't get away with it, usually by fighting in the Netherlands. When the future Charles II and the Duke of Buckingham made their disastrous trip to woo the Spanish Infanta, they got arrested at one point. Locals assumed that a couple of poshos seeking passage to the continent, who both claimed to be called Mr Smith, and were wearing unlikely disguises, were obviously planning on fighting a duel. Ben Jonson got off a charge of manslaughter after he killed a man in a duel, by claiming benefit of clergy, on account of he could read good. In this period, in England, the difference between a duel and a brawl isn't that clear. Everyone is pissed and armed to the teeth, so fatal fights aren't rare, but that doesn't mean people assumed their actions were sanctioned, or thought of themselves as taking part is some formal trial of honour. For example, the poet Thomas Watson had a legal dispute with a heavy called Bradley. Bradley is walking down the street, and passes Christopher Marlowe, the playright, who has taken Watson's side in the dispute. The two men begin to fight with swords. A crowd gathers, but nobody interferes. Watson appears, and joins the fight, at which point Marlowe withdraws. Watson kills Bradley. This isn't a duel as we would imagine it, but it's not a free-for-all brawl. Marlowe clearly felt it was correct to let Bradley fight Watson, rather than the two of them dealing with Bradley together. Watson gets off, eventually, since it was self-defence, but he had to await trial in jail, which would have been a pretty horrific experience, if you didn't have money to arrange some comfort.

|

|

|

|

we are comparing mercenaries to civilians here though, and my subjects are super killy. perhaps the english authorities are a little more OK with soldiers killing one another and i rarely see free-for-all brawls either, usually there's an unspoken assumption that things are going to be done the right way. like the guy who asked another soldier to drink his health, and was refused. he asked him again, and was refused, a few times in a row. finally, the target stood up, put his hand on the hilt of his sword, and said "Here have I this, with this I will drink your health!" but nothing happened until the first guy, very deliberately, took his gorget off and laid it on the table. Only then was it on. The other guy didn't have one, you see HEY GUNS fucked around with this message at 17:28 on Nov 24, 2015 |

|

|

|

Very interesting stuff! I should say that I use the term "duel" overly loosely in my previous post to refer to fights resulting from disputes or perceived injury to honor, etc. The killings mentioned by Davis in Fiction in the Archives are rarely if ever the result of formal combat over honor, if I remember correctly, but are presented as "heat of the moment" violent responses to insult or injury. Which is interesting because the use of such excuses in pardon petitions contributes, or at least plays into, an early modern French concept of spontaneous anger in response to insult or injury as grounds for justifiable homicide. Are there similar concepts in contemporary English law, or are things much more restricted?

|

|

|

|

deadking posted:The killings mentioned by Davis in Fiction in the Archives are rarely if ever the result of formal combat over honor, if I remember correctly, but are presented as "heat of the moment" violent responses to insult or injury.

|

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:we are comparing mercenaries to civilians here though, and my subjects are super killy. perhaps the english authorities are a little more OK with soldiers killing one another How did the fight turn out?

|

|

|

|

Hogge Wild posted:Was horse theft a capital offense? Also, if you called a honourable man unhonourable, how much was the fine? no fine, but you do have to apologize in public and there's a little ceremony. if you injure a guy you have to pay his medical bills though

|

|

|

|

Animal posted:How did the fight turn out? also remember all of this is taking place inside some dark little tavern. there's no room and no light and then a pair of dudes whip their rapiers out. it's probably messy and over very fast

|

|

|

|

When does it start becoming more strictly outlawed to do this kind of thing in Western European armies.

|

|

|

|

|

deadking posted:Very interesting stuff! I should say that I use the term "duel" overly loosely in my previous post to refer to fights resulting from disputes or perceived injury to honor, etc. The killings mentioned by Davis in Fiction in the Archives are rarely if ever the result of formal combat over honor, if I remember correctly, but are presented as "heat of the moment" violent responses to insult or injury. Which is interesting because the use of such excuses in pardon petitions contributes, or at least plays into, an early modern French concept of spontaneous anger in response to insult or injury as grounds for justifiable homicide. Are there similar concepts in contemporary English law, or are things much more restricted? As I recall, the common law defense of provocation required a physical assault on you or your family. This could include unlawful sexual contact, irrespective of consent. So if someone's having sex with your daughter, you cant kill them, but if he's having sex with your son, its on! Provocation is good because it bumps murder down to manslaughter. You can't claim benefit of clergy with premeditated murder but you can with manslaughter.

|

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:but peter spierenburg says that even "heat of the moment" fights follow a common cultural script Hence the scare quotes. I agree with Spierenburg on this particular point. Edit: Also, I think the appearance of spontaneity is important in the particular genre of the pardon request because it helps the offender justify their action and therefore their request for the king's pardon. deadking fucked around with this message at 18:17 on Nov 24, 2015 |

|

|

|

HEY GAL posted:there should be a flow chart here or something: Are swords special here, or could you kill a guy for trying to steal your musket/pike etc.

|

|

|

|

Patrick Spens posted:Are swords special here, or could you kill a guy for trying to steal your musket/pike etc.

|

|

|

|

VoteTedJameson posted:Yes, although it's a little hard to decode. So, the vocabulary surrounding professional soldiers varies wildly over time and can even be internally contradictory. But I have it here that as of 1445 in France, Charles VII instituted a new universal standard of organizing/equipping an army. The army was divided into groupings called 'lances' which consisted of a knight, his sword-bearer (squire, presumably), page, two archers and a varlet- a term which I can't find adequately defined anywhere. It might be another person of squire rank, serving in different duties. So the 'lance' system of organization had been in effect for a long time but as I recall, one 'lance' used to be three men at arms- a knight and his two squires. Mind you, these requirements fluctuate over time due to the demands of war, the availability of nobles (the Piague in 1381 and Agincourt in 1415 are serious impediments) and the ability of the crown to extract minor nobility's military contributions. The reason that the knight is required to bring archers (probably meaning crossbowmen in context) is that this arrangement comes from Charles VII's "grande compagnies d'ordonnance"- meaning that for the first time, feudal obligation is being applied toward making a cohesive and balanced army. Thanks, although I am familiar with lances fournies and the compagnies d'ordonnance and they're not quite what I was asking about – I was asking if you knew of any evidence that a knight was the one responsible for raising/training/equipping the lance. In the compagnies d'ordonnance the king employed all the soldiers directly (although had captains) rather than delegating through a knight, and they seem to be associated with the gendarme more than the knight, removing feudal obligation from the equation. Unfortunately these obligations seem very difficult to track down and identify. It could be similar to the ministerialis class in Germany, where there was so much variation in duties that there may be no clear guidelines to go from.

|

|

|

|

I'm working on something experimental atm. It's a short turkish bow with relatively low drawweight. To make a good performer like the old bows, you'd need to cut the width in half, which will not result in a stable working bow - the core here is narrow. This here is the ridged section, which is only partially bending in the first half in a finished bow. The transition from this to the tip is pretty hard to do, but you can't see it on the pics. The upper section where the ridge flares out is inverted on the other side of the bow, so that the profile kinda looks like a dick. Getting close to finishing this took me half a day on both limbs.

|

|

|

|

Not sure if this is the right thread for it, but is there any truth to the statement that a non (immediately) fatal thrust was more likely to be deadly than a non (immediately) fatal cut?

|

|

|

|

curious lump posted:Not sure if this is the right thread for it, but is there any truth to the statement that a non (immediately) fatal thrust was more likely to be deadly than a non (immediately) fatal cut? To be honest, most fatal injuries don't immediately kill you anyways. People usually take 2 minutes to bleed out, the only blade injuries that will drop somebody in seconds are ones that hit the shallow blood vessels like the femoral or carotid. If you're fine with a simple explanation, wounds from a thrusting attack are probably just a lot deeper than cuts, which makes them more likely to hit something important, and more difficult to clean and dress. It's quite easy to stab a knife into somebody up to the hilt, but nobody besides Conan is going to cut you like that. This holds true for any injury too, the deeper into your body the damage extends, the more serious it is. Slim Jim Pickens fucked around with this message at 12:35 on Nov 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

George Silver kvetched about the rapier way back in late 1500's, partly because he considered it too lethal. (Also because it was Italian and these loving immigrants taking honest English jobs.  ) )

|

|

|

|

Siivola posted:George Silver kvetched about the rapier way back in late 1500's, partly because he considered it too lethal. (Also because it was Italian and these loving immigrants taking honest English jobs. If by "too lethal" you mean "more likely to get both fighters killed" then yes, but he was not out to preserve the life of his opponents or something. that's retarded. Slim Jim Pickens posted:To be honest, most fatal injuries don't immediately kill you anyways. People usually take 2 minutes to bleed out, the only blade injuries that will drop somebody in seconds are ones that hit the shallow blood vessels like the femoral or carotid. or, you know, having your head split open like Sir Henry de Bohun. There are two ways of defeating an opponent with a sword, one is by killing them and the other is by rendering them unable to fight (which can eithe mean dealing them non-lethal blows that sever tendons etc or just convincing them to surrender.) I essentially agree that the thrust is more deadly in absolute terms and taken on their own for the reasons you give, but believe cuts to be more effective to bring a fight to a rapid conclusion. I'm speaking, of course, of unarmored fighting. That said, a good fighter takes whatever opportunities present themselves, and cut and thrust are both essential. I'll end this with Silver's own words from Paradoxes of Defence. For reference, a "short sword" is what you might call a broad sword, and thus short compared to a rapier, it's not something gladius-sized. quote:And now will I set down possible reasons, that the blow is better than the thrust, and more dangerous and deadly. First, the blow comes as near a way, & most commonly nearer than does the thrust, & is therefore done in a shorter time than is the thrust. Therefore in respect of time, whereupon stands the perfection of fight, the blow is much better than the thrust. Again, the force of the thrust passes straight, therefore any cross being indirectly made, the force of a child may put it by. But the force of the blow passes indirectly, therefore must be directly warded in the countercheck of his force, which cannot be done but by the convenient strength of a man, & with true cross in true time, or else will not safely defend him, and is therefor much better, & more dangerous than the thrust. And again, the thrust being made through the hand, arm, or leg, or in many places of the body and face, are not deadly, neither are they maims, or loss of limbs or life, neither is he much hindered for the time in his fight, as long as the blood is hot: for example:

|

|

|

|

Hm. I wonder if I got my British fencers confused and was thinking William Hope instead? He actually did end up renouncing dueling because he came to the conclusion that killing people is not a very Christian thing to do.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 8, 2024 18:18 |

|

Tillering done, moving to make the surface round   The transition done. Quite a complex form  The core is more round near the grip, what I did here is just an educated guess, the finished bows look completely different with the sinew on. Completely flat that is. Most of it is actually on the sides of the limb, just a little in the middle. Grooved and ready   The light was really bad today, so all the pics aren't too sharp. Ready to go   First layer done. 2 more to come.  The naked core had 193g. 62g sinew will be used when it's done. Sal at mid was 24mm wide, 8,5mm thick. Thinnest spot at the Kasan Eye was 22mm wide and 7,10mm thick. The new measurements that I cooked up seem to work. The way that the bow bends here looks like the old unfinished bows. There's always some kind of problem. This time it was a new comb that I used, one made of carbon, not plastic. Bad news is, that the sinew and glue sticks to this material, so you have the tendency for the stuff to tangle up when you have it soaked with glue. Which is about the equivalent of having your foreskin stuck in the zipper. Well, it's just the first layer.

|

|

|