|

First of all hello there and thank you for taking a look at my thread. I hope you find helpful and interesting answers here. Who am I? I am an Honours Class History student in Liverpool Hope University, planning to start my Master’s at the end of this year. In February I become a room & tour guide in Speke Hall (originally a Tudor manor house which later became a Victorian mansion, with a brief career in-between as a cattle shed). Generally I enjoy teaching and sharing information, and I figure this is a much more constructive venue to do that than responding to Youtube debates. What is this about? Medieval History. Anything from the Viking Age to the Teutonic Knights to Marjorie Kemp and what a strange person she was. Any aspects of medieval history that interest you; or any aspects that confuse you and you would like to understand better. Whether food, medicine, technology, daily life, the reasons behind the Crusades. Ask away and I will give the best answer I can. A particular focus of mine is medieval arms and armour. I study medieval swordsmanship from historical manuscripts such as the Talhoffer Fechtbuch – which also contains mad-scientist ideas such as tanks (armoured war wagons with cannons), mobile land-mines with blades, and 15th century diving suits (which are fully functional, if inconvenient). I do not have a HEMA (Historical European Martial Arts) group in my area, but I am familiar with some of the fighting texts and much of the research into the performance of medieval arms and armour. A difference between this and the military history thread is I expect a different focus. This will be part military history, part martial arts, and part social/political/cultural history. Anything else to know in advance? Medieval history is mostly guesswork, so answers will revolve around not only what we know but also how we know and what evidence there is to support that conclusion. A lot of answers will have a simple version and more nuanced and detailed version. I like busting misconceptions. A huge amount of what people think they know about the medieval world turns out to be completely wrong. Actually that is true for almost any area of history, but the medieval world is the area I feel most qualified to answer in detail. University does not like me keeping a sword on campus, so if answering your question means testing things out with my practise sword then you may have to wait until the weekend for a full answer. Let the questions begin!

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 27, 2024 09:42 |

|

Karl Fungus: Many common fantasy “medieval” weapons were used somewhere at some time. That somewhere might not have been a very large place, and that some time might not have been very long, although generally fantasy weapons have a loose tie to reality. Except for double-headed axes. That is the one weapon off the top of my head I can say was never used in battle. There was a huge difference between armies of 700 AD and armies of 1400 AD, although the most common weapon for either was a version of either a bow or a spear. The spear of 700 AD might be 7-8 foot long and used with a shield, while the spear of 1400 AD might be a pike (10-20 foot spear) or a halberd (combine a spear with an axe). The bow of 1400 AD might be crossbow. However, bow or spear is the broad theme. Bows and spears were relatively inexpensive, might be used for hunting, and being able to attack without the enemy attacking you was a huge advantage. According to Konungs Skuggsja (a diverse text from around 1250) one spear was worth two swords in a shield wall. Using a bow also allows an unskilled fighter to fight at less risk to himself. Swords, axes and maces were used, although were typically not primary weapons. Exceptions did exist, such as the Dane Axe or Scottish Claymore, although these were not particularly common. The first weapon was always the one that could strike from further away, and then the secondary weapon is drawn once you get closer. These weapons also changed significantly over the medieval period. Actual swords tended to be reserved for the wealthy, although cheaper options existed that resembled oversized knives – these could be the seax in early medieval Europe, a messer in later Germany, and later on cheaper swords for pikemen such as the Swiss Degen and German katzbalger become possible. Most medieval armies were properly equipped for battle. Some places (England, Denmark) had militia laws requiring every man above a certain level of wealth to keep weapons and armour, others (France) tried to forbid the peasants from owning weapons but relied more on household troops. The German & Italian states varied too much for me to easily keep track of, although I think they tended towards armed. Flails were mainly used in the Hussite Wars, although mainly saw use in East Germany during the 1400s. The advantage is most peasant farmers had used a flail to thresh grain, so he would know how to use a version adapted to combat. It seemed to be used about as much as the pike according to ordinances. For example, Duke Albrecht V ordered in 1421 that of every 20 men, there should be 3 handguns, 8 crossbows, 4 pikes & 4 war flails. It also tells us something about Duke Albrecht’s maths (3+8+4+4=19, not 20). LUMMOX: I have never really experienced hot debates in medieval history, at least not within scholarly circles. Instead there is just straightforward cases of either outdated information (such as with medieval sword use, the concept of the Dark Ages) or a disconnect between scholarly research and popular culture (attitudes towards the Crusades, views of medieval science, and so on). The closest answer I could give would be to give a list of common misconceptions about the medieval period. On medieval combat, the chief debate I can think of is whether the longbow is really able to pierce plate armour or not (the answer: not reliably). I hope those help!

|

|

|

|

Zombieswithblender: Castle sieges were the most common way to conduct medieval warfare, although assaulting the walls was a last resort. Actually it was battles that were avoided if possible, unless you were confident of victory, because a battle that goes badly meant losing your army, which was difficult to recover. Instead, you tried to avoid exposing your army to risk. Raiding or indirect warfare was popular. The English during the Hundred Years War used raids called chevauchees against the French, where soldiers would sweep in burning villages and sweep out. The idea was to reduce productivity of the land and a bizarre PR-campaign. A feudal lord had a responsibility to protect his population, and a chevauchee proved the lord was failing that. In practise, the PR campaign tended to cause disorganisation, but also earned a lot of hatred. Good examples are the raids by Edward the Black Prince in his 1355 campaign laying waste to the lands of Armagnac, which caused the count to lose a lot of support. He launched them again in 1356, 1373, and 1380. The interesting thing is there did not seem to be much of a solid goal to those campaigns other than loot and pillage. Again it was used by William the Conqueror during the Harrying of the North. Essentially rather than fight the rebels he would slaughter civilians, burn crops and destroy livestock, and just let people starve over the winter. That said, William did get criticised in a lot of chronicles for the extent of this. Orderic Vitalis says “I have often praised William in this book, but I can say nothing good about this slaughter. God punish him.” Al-Kutami, an Umayyad (Moorish) poet wrote down “Our business is to make raids on the enemy, on our neighbour and on our own brother. In the event we find none to raid but a brother.” If we look at Frederick I’s invasions of Italy, there was the Siege of Crema (1159-1160), the Siege of Milan (1161-1162) and the Siege of Alessandria (1174-1175). There were battles in between, such as the Battle of Tusculum. However, where a battle could be won or lost in a day, each those three sieges crossed the boundary from one year to another. Months would be spent besieging a castle or a city, possibly sapping/undermining, possibly bombardment, rather than sending troops forward. Ferdinand: Europe probably did get gunpowder from China in 1242, introduced to it by the Mongols. In fact a term for gunpowder was “Chinese snow”. Paper was introduced through Islamic Spain to Europe in the 1200s as well. The most important imported technology in Europe was Arabic Numerals, the numbers we use today. Before that they used the I, II, III, IV system of the Romans. Most inventions, however, were not imported from Asia. The compass appears slightly later in Europe than the compass in China (1186 Europe, circa 1040 China) but before the compass spread to the Middle East (1232), and independent invention seems more likely than the compass spreading from China to Europe without crossing the space in-between. Alphadog: Doing a brief read-around I have not found that debate, although it sounds interesting. I have not come across it in my research, however. As far as I knew, the clothes Vikings or Norse peoples wore were described by other sources and artwork as well, although that would be biased towards the upper classes and people who generally appeared in tapestries. There are lots of references to tunics, I think Dorsey Armstrong describes a humorous anecdote about a thing a man keeps beneath his tunic, to put in a hole he has put the thing in many times before (referring to a key). Trousers get described in the sagas, such as Fljotsdaela saga, where the trousers of Ketill Prioanderson are described as having no feet, but straps under the heels like stirrups. Does this mention mean trousers were supposed to have feet? So overall I would be surprised if there was such a heated debate on the subject, just because there are other sources such as tapestries or the sagas that can tell us what they wore during the Viking Age. However, if you do come across anything on that debate, please send it to me because I would love to learn more about historiographical issues. Avalanche: If you want a good archer, start with the grandfather. Or so the saying goes, most often applies to longbowmen. Most English longbowmen had distinctive skeletons, such as those found on the Mary Rose. Twisted spines, grossly enlarged left arms, bone spurs on the wrists, shoulders and fingers. This is because the draw weights are so high (100-120 lbs seems to be the average, although with some in the 150-180 lb range). Quite a few laws required archery practise in England. Edward III in 1363 decreed weekly archery practise on Sundays, supervised by village priests. In 1477 Edward IV banned a cricket-type game because it interfered with archery practise, and Henry VIII passed statutes on archery in 1515. I have heard it even goes back to the 1252 Assizes of Arms but have not been able to confirm that. No weapon ever truly required a lifetime of training, although many are much more skill-based than others. A trend I notice is single-edged swords tended to be more common among the less-skilled troops, while the knights and elite professional warriors preferred double-edged swords (because you can use lots of cuts with a double-edged sword that are not obvious). My favourite weapons are things like the bill-hook, which is essentially a modified gardening tool. Nearly any farmer would be familiar with how to use it, which would cut down on training time considerably. I am running low on time but will answer the rest of your questions when I get back. Svarotslav: Thanks for the heads up, I have a little more to say on that subject when I get back. Tzikourion seems to be a general term for axes. The archaeology on them seems to be kind of complicated, with single heads and spikes on the back that apparently can slot together into a double-headed construction. I will post images when I get back.

|

|

|

|

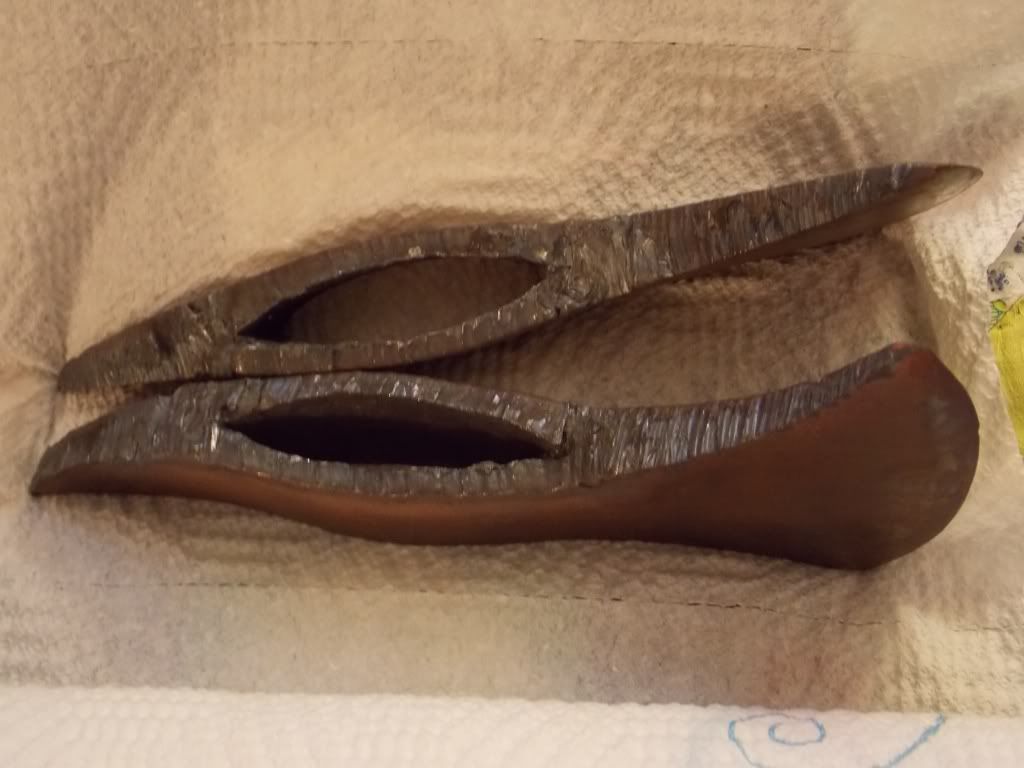

Avalanche: Part II, Knights. Knights were extremely skilled warriors. Early on, they were death on horses. Later on, fighting on foot became more common, at which point knights became death on legs. Most of our evidence is concentrated from 1300 and later. The main reason for this was because that was when the fighting classes became more literate. Before then, the people who knew how to fight were not the people who knew how to write books, which limited how much information survived today. However, what we do know seems to imply that it was in place beforehand. First of all, we can look at the martial arts. If we look at the fight-manuals such as the I.33, the Talhoffer Fechtbuch, Flower of Battle and Nuremburg Handschrift, they all depict advanced and sophisticated martial arts even from the limited picture we have of them. Johannes Liechtenauer, an early fighting instructor from the mid-1300s, claimed that everything he taught had already existed for centuries. Actually his teachings included relatively recent weapon designs like the longsword, but I interpret it as saying that fighting techniques relying on the same principles existed before. Second is athleticism. The Towton Graves indicate knights or men-at-arms had fairly distinctive skeletons too, such as separations in their shoulder blades that come from vigorous exercise beginning at early childhood. Highly developed arms similar to tennis players. We definitely know knights during the Wars of the Roses were extremely physically capable men. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y-gcvq7Vk90&t=6s For more on athleticism, the works of Marshal Boucicaut aka Jean Le Maingre, describes an exercise regimen and the feats a knight was expected to be able to do. Example feats: Leaping onto horseback in full armour (no cranes required, you should be able to jump onto the horse unaided). Turn somersaults whilst clad in a complete suit of mail (save for the helmet). Vaulting over a horse. Climb between two perpendicular walls standing 4-5 feet apart by mere pressure of his arms and legs, without resting on either ascent or descent. Climb the underside of a ladder using just his arms, while in full armour. Doing the same without armour, but only with one arm. Watch gymnastics and imagine doing that stuff wearing 50-60 lbs of armour. From that evidence we know knights at the time (1300-1450 for those sources) trained extensively like athletes, presumably with the same willingness to endure discomfort as any athlete would have. Sources that directly tell us how skilled knights of the day were are harder to find (read: I can’t think of any :P ) but their athleticism tells me they took their training seriously. We have less information on earlier times, however the Annales Lamberti of 1075 complained about the physical fitness of labouring peasants, implying that the warrior class were expected to be more fit. If we know they took their training seriously and they had access to sophisticated martial arts, I would expect them to be highly skilled fighters. Thirdly is the social system, which is why I think earlier knights were also just as highly trained. Feudalism and the institution of knighthood were structured to support an elite class of full-time warriors trained from childhood. In many ways the education of a knight mirrored that of a guild craftsman who was first an apprentice, then a journeyman, and finally a master. Except with a knight his trade was war. A knight began his career between the ages of 6 & 8, when he was sent off to another nobleman’s court. He started off as a page, which was partly a glorified servant but received part-time military training. Often the servant work would toughen them up, such as pulling wooden horses on wheels so that older squires could practise jousting, so it would help build up strength. At ages 13 or 14 he became a squire, apprenticed to a knight, if he has demonstrated an aptitude for being a warrior. This would act mostly as a support troop, managing a knight’s horses, bringing him fresh lances during battle. In many cases a squire would protect his master if the master was injured, or guard prisoners. Normally, between ages 18 & 21 one would be knighted, ideally having either proven ones skill or shown valour in battle. This system was in place from early on, so I doubt they would have such a detailed system of raising knights and not train them well. Additionally devices like the Pell or Quintain used for training also existed early on. Occasionally people did get knighted for other reasons, such as Balian of Ibelin knighting 60 men in the defence of Jerusalem, or a Holy Roman Emperor (Sigusmund) knighting a peasant to stop a knight from abusing his rank in a legal dispute. However, the knight as a military figure as opposed to a social title was about as skilled a warrior as was likely to ever be. Part III, Commanders. Early on, commanders routinely fought alongside their troops. Perhaps not the infantry though. At Hastings, William the Conqueror was participating in attacks on the Saxon shield wall, enough that there was a suspicion he had died and he had to take off his helmet to show everyone he was alive and well. Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick fought on foot at the Battle of Barnet to show his men that he had no intention of fleeing. Which did not work out well for him due to a friendly fire incident. I also think Warwick was described as "with great violence he beat and bore down all who stood before him." Henry V fought near the front at Agincourt, I think his helmet got damaged, and before that he was known to have a scar from being shot in the face with an arrow. John of Bedford led a charge by the English men-at-arms at Verneuil, after the French/Lombard/Milanese cavalry had scattered his longbowmen. At the Battle of Lewis it was a nobleman leading the charge. Overall, I think it would be more noteworthy to find a commander who didn’t take part in the charges. It started happening more towards the 1500s, but it was far more traditional for a king or duke at the head of the army to be kicking rear end and taking names. Svarotslav: I looked into Tzikourion, and it seems to be a general word for axe. The Tactica of Leo (900 AD) says the cavalry should have a double-edged axe, although then says one edge should be long spear-like point. Others had a long protrusion like a hammer face on the back. Apparently there is mention of some axes being like the bipennis (which was a double-headed axe, strictly ceremonial, and later used as a symbol of both fascism and feminism). What I was thinking of when I mentioned double-headed axes was the larger fantasy-style axes, which would just be a huge extra weight on an already heavy weapon. I imagine with a much smaller axe it would be plausible, although I would much prefer a spike or a hammer on the back so my weapon could be multi-purpose. The image I wanted to post would stretch the board, but it shows the curved back-spike of one head fitting snugly over the axe-side of another, and vice versa. All the archaeological finds I can see are single-headed, although with a point or hammer or something on the back. What I did find that was interesting was two axeheads together could be placed on top of each other and fit together to form a double-headed axe shape. However, I learned something from that, so thanks for letting me know! ASIC: Early on they used a type of furnace called a bloomery which was essentially a glorified chimney with air forced through by bellows. This initially produced a mix of iron and slag called sponge iron, then it was shingled which means drawing out under a hammer, which probably involved gratuitous beatings. Eventually these got larger and larger, which is just as well because you would only get 1 kg of iron at a time. Eventually they moved onto the blast furnace that could produce fully molten steels, as well as crucibles. This was economical in that it could provide larger amounts of iron/steel at once, and it also was less work because it could produce more homogenous steels. The early bloom steels required pounding, folding and welding to be high quality steel – similar to Japanese tamahagane. Or you could carburise the surface to harden the iron. Alpha Dog: I think later hose were more sock-like in design, with full feet. Often hose were combined with breeches, so the breeches would be the pants and the hose would be essentially glorified socks. My main concern when judging Viking Age clothing was warmth. If it is practical, warm and comfortable, it makes sense for Vikings to use. Grave goods were probably fancy, but trousers and tunics are a pretty safe bet. They could definitely work designs in. Pattern-welding was sometimes layered on top of a soft iron core, which would say it was decorative rather than functional. How detailed these designs got I am unsure, but they could definitely use it just for decoration. Heimskringla seems to be more accurate the further forward in time it goes. The first few sagas are believed to have been essentially made up, but more credible the nearer to the 13th century the sagas get. For me, it is still valuable as a resource of the time, because even exaggerations tell you what people felt a need to exaggerate, which is an important aspect of my dissertation. However, I am just parroting the established consensus rather than conducting an analysis of my own. Railtus fucked around with this message at 15:55 on Jan 23, 2013 |

|

|

|

Nelson: Specific diets for knights do not seem to be well known. The MS_3227a (Nuremburg Handschrift, or Codex Dobringer) seems to have food recipes despite being largely a martial arts manual, although that could be general, not just knightly. It also has magic spells in there. Some organisations like the Knights Templar or Hospitaller would sometimes be required to eat like monks, essentially living off bread and vegetables, yet it never seemed to impact their fighting prowess. No superweapon truly existed, although game changers would be the advancement of cannons in the 1400s. Older castles were designed with higher walls and often a square shape to maximise the space enclosed within its walls. These forts were vulnerable to cannons. Later forts would then be built resistant to cannons, but the castles that had dominated in previous centuries stopped dominating. Another game-changer was the adoption of munitions armour. These are cheap sets of plate armour for foot soldiers that do not require fitting to the individual soldier. Not as good as a knight might wear, but it will still stop a sword or a spear or an arrow reliably, and that resembles the general pattern – instead of investing massive resources into one man (the knight) you can get a more cost-effective use of resources by having cheaper infantry with mass-produced equipment. There was an idea for tourism, normally under the guise of pilgrimage. The Canterbury Tales was actually fairly realistic in describing pilgrimage as a semi-social event. Margery Kemp went on a lot of pilgrimages, while her fellow pilgrims kept trying to ditch her. Anyway, things like pilgrimages were great excuses for vacation. If you could afford it. One thing people did for entertainment was carve the medieval equivalent of noughts-and-crosses on the back church benches. Pews were not standard, but those that did exist had some interesting carvings on the back.  Hunting and hawking were considered recreation for the nobility, and hunting was important as training for war (if you want practise fighting for your life, engage a boar in hand-to-hoof combat). Dancing was extremely common. I’ll try to think of others. Hunting and hawking were considered recreation for the nobility, and hunting was important as training for war (if you want practise fighting for your life, engage a boar in hand-to-hoof combat). Dancing was extremely common. I’ll try to think of others.Sweevo: A go-to guide for medieval tactics and strategy was De Re Militari. Early tactics seemed to involve the shield wall, to give as much mutual protection as possible. The idea was to break their shield wall while keeping your formation in good order. One way this was done was through tools like the Dane Axe – a mail-clad Saxon huscarl could hack down on the unshielded side (there is a rumour they used their long axes left-handed on purpose) and disrupt the formation, causing enough of a break for your own shield-wall to capitalise. An important tactic was combined arms. The English in the Hundred Years War combined dismounted knights using pollaxes with archers, the idea being that the archers can shoot directly at the approaching Frenchmen and then step back behind the cover of the knights once the French get closer. Later on you see fully armoured knights or doppelsoldners mixed in with the pikemen, to hack down anyone who gets past the pikes or to exploit breaches in formations. Field fortifications were important. Again, the English in the Hundred Years War would use fields of sharpened stakes to prevent cavalry charges, which worked early on (Azincourt & Crecy) and failed elsewhere (Verneuil & Patay). This was also used in Laager or Wagonburgs in the Hussite wars, which was literally creating a fort by making wagons in a circle and using the wagons as shooting platforms. A few had planking and cannons installed specifically to assist this purpose. Pike formations became popular later on, pioneered by the Swiss (although largely with the help of ambush and ferocity) which later inspired the German Landsknecht and Spanish Tercio. The Scottish also used early pikemen. It was noted the best place to charge a pike square was on the rear corners. A circle or schilltrom could be formed, but if the pikemen defend all sides at once, they make an excellent target to shoot at. Those are off the top of my head. Obvious stuff like flanking, cavalry charges and so on were also important. Godhio: That is a really good description of the transition from medieval to renaissance warfare. I like it. I would say training and organisation. I do not know any historical languages; to be honest I think I would really struggle to learn them. If I get a good chance I will, but I think it might be difficult. Ed: Honours Class means I’m in my 3rd year of a 3 year Bachelor’s Degree. It sounds better than 3rd year student so I go with that.  I will try to start using quotes. I cannot guarantee I will always remember, and these forums are different to the ones I usually use, but I will do my best. Reading through the forum rules there seems to be no rule against double/triple/quad-posting (am I correct?), so I could give each reply its own post with a quote. Would that help? Railtus fucked around with this message at 20:14 on Jan 23, 2013 |

|

|

|

Moridin920 posted:Use the [timg] tag, it'll adjust the image to a thumbnail that expands to fit the board or to its full resolution depending on where you click on the thumbnail. Thanks!

|

|

|

|

Trump posted:Awesome thread. I've been wanting to get into the middle ages a bit, is there any general overview works you would recommend to get started? Thanks! That helps a great deal. Dusseldorf posted:You mention raiding villages? Were wholesale atrocities on the opposing serfs commonplace earlier in the 100 years war like what happened later in the 30 years war. I assume having a roving army in your countryside is at the very least bad for the food supply of the average peasant but did it also result in every male of age being strung up in a tree? To what extent was medieval war "total"? Not to the same extent, although still pretty bad. Chevauchees were essentially acts of terrorism, PR campaigns designed to undermine the French king by proving he could not protect the French people. Of course Edward the Black Prince needed survivors for his point to be proven to, so the slaughter was not generally that severe. I think slaughtering the population was typically not the done thing, although it did happen on occasions the city was taken by storm (such as the capture of Jerusalem in the First Crusade). However, medieval war was sufficiently harsh on ordinary folks that militia became very popular later on. So I guess low-level atrocities were more the thing? JoeCool posted:What was the deal with self flagellation during the black plague? An imaginatively named cult called the Flagellants took one form of penance – mortification of the flesh – and got carried away. The idea is that there are many ways you can repent for sins, prayers of contrition, good works, pilgrimage, although a few monks would occasionally beat themselves. Because nothing says sorry like self-harm. They were a heretic cult during the 13th & 14th centuries, cast out from the church for their practises. The essential belief that made them grow to the extent they did was that by repenting for their sins they could receive some kind of protection from the Great Death or the pestilence. That the church cast these guys out implies some measure of disapproval, so I don’t think their position was the mainstream of the church. Earwicker posted:I have read in a few places that clean water for drinking was relatively rare for most people in medieval Europe and so everyone constantly drank beer or other alcoholic beverages instead. Is this true or a misconception and if it's true how anyone get anything done and why didn't people constantly die from dehydration and alcohol poisoning? Absolutely. LUMMOX gave a good answer. Essentially regular alcohol could be quite watered down, so you get more water from the beer than you need to digest it. An interesting thing is if you look at the medieval peasant diet, it was very low on calories and high in vegetables. Now pair that with the fact that heavy drinkers get an ale gut because of how calorific most alcoholic beverages were. One problem was used to solve the other. However, with alcohol being a staple, I wonder if Foetal Alcohol Syndrome was particularly common back then. AlphaDog posted:Thanks again! I struggle to think of any off the top of my head, but it is an angle I am using for debating the reliability of William of Tyre’s Historia and accounts of how the Crusader kingdoms treated their Jewish and Muslim population. I have heard it be suggested William of Tyre’s work might be propaganda meant to glorify King Baldwin. However, if it is propaganda, then any suggestion of Baldwin showing kindness towards Jews & Muslims – whether true or false – would be a sign that such kindness was considered admirable according to the people of the time. Another example is the myth of Prima Nocta, or Droit du Seigneur – rumour was that a lord essentially had first dibs on the virginity of a woman on his land when she got married. The rumour is false; every contemporary source that mentions anything of that nature is accusing an enemy of it and using it as an example of how evil and corrupt they are. What tells us is 1: everybody thought it was evil, and 2: nobody thought it was acceptable. Between those two things, we can be very confident it was neither a law nor a custom in western Europe (also, that law is not on any of the books, and no woman was ever identified as having suffered it or even commenting on the practise). EDIT: Apparently there was one reference in Zurich to lords interpreting a bride-pride or marriage fee to mean this, but this was also in the context of the church condemning them for abusing their position of power to sexually harrass their subjects. In Ancient Greece they used to use wine to disinfect water (in my Classics A-level I remember one person was notable for only adding the minimum of wine to his water for it to be safe to drink), so I lean towards the alcohol kills germs theory just because it worked for pre-medieval peoples. However, boiling + alcohol is certainly more thorough. Railtus fucked around with this message at 13:09 on Jan 24, 2013 |

|

|

|

Aggressive pricing posted:Cool thread, I was wondering if you could expand on something: A little of both. At Hastings the knights rode up and down the hill with fresh spears, which must have been exhausting work. In 1066 they were still using spears rather than longer specialised lances, so often they would just throw the spear and ride down for fresh spears, although they would couch (tuck the spear under their arm) as well. For more general lance charges, if the enemy formation is still intact after impact you generally do not want to stick around in a prolonged scrum of fighting - too much risk of being surrounded & mobbed. Also a risk of your horse being killed, since particularly in the earlier years horses were often less armoured than their riders. A mounted knight will make short work of individual infantry (ie: a broken formation), but drawing his sword against a solid shield wall is playing to his weaknesses. If they resist the charge, it is better to ride off a short distance and your squire will ride forward with a new lance for you, so you can be back into the fighting quickly. A point I should make here is that war lances were never designed to break on impact. Only tournament or sporting lances broke on impact. The entire design of the lance was to maximise the amount of force the lance could deliver from the horse's charge, and designing the lance to break would be counterproductive to that. A good example of lance design is provided by the ever-enthusiastic Mike Loades - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NblAIujdzeU&t=2s - starting around 2:20 If knights used their lances on foot, such as at the Battle of Arbedo (1422), using the lances was very similar to a pike formation. If you lost your lance, and the enemy had not got close enough for you to draw a sword or a dagger (by the way, daggers were VERY important), then you could step back and let the man behind you take your position. Go to the back of the formation, and again your squire should hopefully have a new lance waiting for you. This is mostly speculation, but that is how I would do it. Chamale posted:How did health affect the effectiveness of troops in medieval times? I imagine most soldiers were much weaker than they could have been due to malnutrition, sleep deprivation, dysentery, and various other conditions. Health was a major factor in medieval troops. More soldiers died from disease than combat, which makes sense considering that the preferred method of war was to attack supplies or rely on siege rather than direct battle. However, the English at the Battle of Azincourt were suffering from illness and still won. A more complicated version is called Nine Mens Morris. I cannot remember what the basic version is called. I am listening to Dorsey Armstrong, the Medieval World (the Great Courses are awesome), to find out what the game was (she was my source). Earwicker posted:Am I correct in assuming that if a person from the Middle Ages were to somehow fall into a time machine and show up in 2013, that anyone who met them would probably pass out due to their hideous stench? Heck no. Medieval people were no less clean than in any other period, and probably much more clean than people in the 19th century. Missing a bath was sometimes imposed as a penance for a sin, which tells us that bathing was standard. Most towns and even villages had public bath-houses (Etienne de Boileu wrote down some regulations for the Parisian guild of Bathhouse Keepers in 1270). As far as I am aware archaeological finds include wooden tubs or even barrels lined with padding on the inside, used for bathing. Medical texts such as Physica by St Hildegarde of Bingen includes instructions on washing. Compendium Medicinae (1240) gave careful instructions on washing, and also discusses treatment for body odours, strongly suggesting medieval people were at least conscious of the subject. Chamale posted:Conversely, if a person from 2013 somehow ended up in the Middle Ages would they most likely get burned as a witch, die of smallpox, become a beggar, or use their futuristic knowledge to get rich? My suspicion is the modern man would become a beggar. Look at the conveniences we are accustomed to? Our futuristic knowledge is mostly theoretical, I know gunpowder is a mix of charcoal, saltpetre and sulphur, but that does not mean I am in any way qualified to make it. I know adding carbon to iron produces steel, but that does not mean I could use it effectively. Maybe being literate would help? Although even that would need adapting. I think the best chance for a modern man would be the monastery. Witch burnings were not that common in the medieval period. That was much more of a 1600s trend. In fact, until the 1300s, the church considered witchcraft a delusion and it was heresy to accuse someone of it.

|

|

|

|

Answers somewhat short because it is late, I am tired and have class in the morning.Ron Don Volante posted:How accurate is the popular depiction of the Medieval era as the "Dark Ages"? If the Roman Empire hadn't fallen, do you think things would have been vastly different? The idea of the “Dark Ages” (a time of ignorance and superstition) is completely inaccurate, I would go so far as to say it turned 180 away from accurate and started running. The medieval period included the Carolingian Renaissance (Charlemagne’s drive for education), the establishment of universities, it was the time when persecution of alleged witches was forbidden by the church (Council of Frankfurt 794, Lombard Code 643, Canon Episcopi circa 900). It was the copying of texts by Irish monks to thank for how much ancient history survives. Technology includes central heating through underfloor channels (8thC), mechanical clocks (13th/14thC), the blast furnace (1150), water-powered trip hammers (12thC) and the printing press (1440). Spectacles/eyeglasses were made in 1286. Admittedly most of this is elite culture, middle-class and up, but the point is the medieval world still had some amazing inventions. That said; we did lose a lot with the fall of Rome. However, Rome was already in decline, the barbarians were growing stronger, and I think the circumstances that would allow the Roman Empire to survive in the west would have made Europe a very different place by themselves. Much of Rome’s military technology was copied from their neighbours. A different balance of power would be needed for the empire to survive. Arnold of Soissons posted:Coming back to this: is there reason to believe that these were commonly attained goals )like the President's Fitness goals) and not theoretical No True Scotsman goals? In other words, is it reasonable to assume that the average knight could actually do these things, or were the merely laudable examples that he ought aspire to? Good question. I am not sure how many of these feats were common. Some of them, like leaping onto a horse in full armour, were presumably expected – I often read that for a knight to fail to do that after his knighting ceremony that would be a cause for great embarrassment. Others, like cartwheels in armour, are easy. Overall I suspect those exact feats were not uniformly expected (I doubt the training knights received was regulated enough for that), just that these feats were examples of how a knight or squire should train. Geoffrey De Charney (14thC knight) did criticise overweight knights, so it is clear not all reached those standards. I would assume the average knight could do quite a lot of those things, just from their bodies. The Towton Graves example mentioned earlier. Another sign is the armour; Dr Tobias Capwell points out that knightly plate armours were typically tailored to the individual warrior – if you look at the Wallace Collection these armours are overwhelmingly designed for men with deep chests, broad shoulders, narrow waists and well-proportioned thighs. Later armours, the munitions armours of the 16thC and later, is when that trend disappears. Also munitions armours tend to be more drab and lower quality metal. This is not something I have studied in detail - and I really should - but it is a trend I have noticed in armours surviving in museums.

|

|

|

|

Earwicker posted:Hey just want to say thanks for answering my questions and the others, this has been a really great thread and you really know your poo poo! You are welcome! Thank you for the kind words. ScottP posted:Excellent thread already, thanks! Glad you enjoy it! Most information I have on mercenaries is towards the later period, because the growth of urban centres meant more and more warriors were independent the rustic feudal economy. The condottori of Italy grew out of the 1200s and became big around 1400, the landsknecht were from around 1490, the Swiss Reislaufer emerged from around 1300, etc. Earlier than that, mercenaries only show up occasionally. Norse and Saxon peoples (including King Harald Hadrada) tended to travel all the way to Constantinople to serve in the Varangian Guard, which hints to me that the opportunities for mercenary service in North and West Europe were probably not that reliable. If you entered under some lord’s contract, you were expected to stay on as his household warrior more or less indefinitely. From what I can tell, formally recognised mercenary companies were rare, although centralised authority was so weak in places that lords might sell military support to foreign powers. So a mercenary might be a lord’s warrior or a bandit, but whichever he was, he was that thing first and a mercenary second. KYOON GRIFFEY JR posted:To expound on a couple things about the so-called Dark Ages, it's actually incredible how non-innovative the Roman world was. I mean there were some pretty impressive engineering achievements, but the Romans were basically cribbing things off the Greeks and improving their deployment, and peoples' accesses. They weren't actually inventing new things wholesale. In fact, it's not entirely unfair to view a significant portion of the Roman period as relatively stagnant in terms of technological development. In some sense, the "Dark Ages" were actually significantly more inventive, although access to technology and information was definitely curtailed compared to Rome. The Romans cribbed off everybody. Mail was copied from the Celts. The favoured form of steel was Noric steel from Austria. I think the gladius hispaniensis was originally Spanish, and the pilum was based on the soliferrum. Apollodorus posted:What's the name for those big centre-grip shields with the spiky ends from the Talhoffer fechtbuch? The only name I have found for them is duelling shields, or judicial duelling shields. The idea behind them was to be as strange and unconventional a weapon as possible. That way, a duel is a “fair fight” because neither combatant is expected to be skilled with that particular weapon. AlphaDog posted:I have a mail shirt from my reenactment days. It's made out of thicker than historical rings because those were what I had. It weighs just under 19kg, or about 42lbs. It turns out I can swim in it. Not very far, and probably not with the padding, but I won 50 bucks off a friend who said there's no way whatsoever it could ever be done by anyone. Is your mail butted or riveted? I notice modern mail tends to be heavier, probably because with butted mail it needs thicker wire to hold its shape and structure.

|

|

|

|

Earwicker posted:What are your thoughts on how average people constructed national/tribal/ethnic identities in this time? I understand that in general "nations" as we know them today did not really exist and it was instead a system of land belonging to various lords who swore fealty to nobility and royalty, but I'm wondering more how people thought of themselves. Did people typically think of themselves as Saxons and Jutes for example or are these tribal identities something that modern historians use to talk about these times, and maybe the people just thought of themselves as living on Lord So-and-So's land? It seems like a time when a lot of these things were sort of in flux All of the above. In England, a Norman/Saxon divide existed up until the Hundred Years War, when a concept of "Englishman" was created to raise support among the French... despite the fact the English crown was fighting the war on the grounds that they were the rightful heirs to the French throne. However, that the English people bought the notion of "Englishman" tells me that maybe Norman/Saxon tension was already on the way out by this point. In Spain, people thought of themselves as not-Moors & Moors, since the Iberian Peninsula (Spain & Portugal) was ruled by African Muslims between 700 & 1000 AD. During the Reconquista, religious identities were the most important, which was probably why Spain became such hardcore Catholics - I sometimes joke that Spain was the most Catholic place in Europe, followed by the Vatican. That said, Spain also developed a concept of racism around 1350-1400, since a lot of Moors who "converted" to Christianity to avoid discrimination remained Muslim in secret, and soon dark skin became a mark of Muslim sympathies. In Germany, people were very divided. To some extent there was a sense of being Bavarian or Franconian etc, but they seemed to organise themselves more into Leagues. You would get Leagues of Knights, Leagues of Cities, etc. France I know less about. I have heard that Parisian French only became the dominant language in the rest of France much later, and there are references to the Flemish, Burgundians & Normans as a distinct group. However, there also appeared to be something more of a shared Frankish identity as well. Italy never existed as a political body at the time, each city state was very independent, so there was a clear sense of being Venetian or Milanese. So England had a concept of race or ethnic group, Italy identified by city-state, Germany identified primarily by their local political body, France was a mix of the lot, and Spain identified primarily by religion. These are generalisations, but it seems to be the trend.

|

|

|

|

GyverMac posted:One thing I've always been curious about, is the armour of the Normans when they invaded england. On the bayeux tapestry they are all shown to wear scale armour, but that was probably just due to the fact that depicting chainmail would be really hard on that particular medium. So i assume they used chainmail, but was it just the nobles that used it? Or did the entire army use it? First things first, yes it was probably mail. To me it looks like rings sewn too large since depicting every individual ring would be ridiculous. Another thing is the Bayeux Tapestry was made by lots of people; some sections were even stitched by children, so the many different people working on the Bayeux Tapestry may have chosen to different ways to show mail-armoured knights. That said, scale armour was known. Not common or popular, but known. Not the entire army used it; you can see a lot of guys in the Tapestry on horseback carrying spears and shields but only wearing what looks like a cloth tunic. Knights would wear mail, so would some of the more well-off serjeants (the word coming from “to serve”), although most of the others would wear cloth armours often called gambesons. gyrobot posted:So what led to the trend of "lightly armored warrior with either a hulking sword or is a brilliant duelist" can easily overwhelm men in armor? The Barbarian simply just use sheer strength to overwhelm the guy without armor to weight him down while the guy who is a duelist can outfence the guy with a sword and broad before striking him down with a knife in the throat A few misconceptions led to those ideas being popular. First of all, in the 1600s heavier suits of armour were made for cuirassiers (pistol-armed cavalry) to better withstand the more powerful firearms of the day.  The dent in it is a “proof mark” to show it can stop a bullet (whether pistol or musket is unknown). Anyway, these armours might weigh 80-100 lbs, whereas medieval plate armour was typically around 60 lbs for everything. So this gave later people an inaccurate idea about armour. Second is jousting armours were routinely heavier than battlefield armour, for obvious reasons. All you are doing is staying on a horse, so mobility is less important. And you are intentionally crashing at 50 mph (assuming both horses charge at 25 mph) which means thicker armour is more important. Between these two factors, later people overestimated the weight of medieval armour, and therefore its effects on mobility. As far as I know, the barbarian image was based on later media surrounding Conan the Barbarian. Not the original media, since in the Robert E Howard stories Conan would wear armour whenever possible. It is also worth pointing out that in every real “barbarian” culture, whether Goths, Celts, Saxons, Vikings, Gauls, their elite warriors would almost invariably favour the most extensive armour they could find. As for the brilliant duellist, this was caused in an imbalance between military and civilian swordsmanship. Battlefield swordsmanship became less and less important by around 1600 when guns were the dominant weapon on the battlefield. Meanwhile, civilian swordsmanship based around the rapier was still practised, although it got less and less realistic over time as it became more a sport and less a method of self-defence (rapiers in the 1500s were for street-fighting, not polite duels). By the 1700s, medieval-style swordsmanship designed for the battlefield was largely unknown, and 1700s-era fencing simply did not work with older medieval swords that were never designed to be used that way. With the cultural supremacist attitude typical of the Enlightenment era, the fencers of the 1700s assumed that medieval warriors had no skill or technique to their fencing. It was the same arrogance that promoted slavery and colonialism being applied to their past. I should mention rapiers rarely saw use in battle. Even in the 1650s, soldiers preferred wide-bladed cut-and-thrust swords. One reason is rapiers were poor against armour. Another reason is a rapier had less stopping power, a stab that kills someone does not necessarily kill them quickly enough to stop them from taking you with them. Wider-bladed cutting swords could leave a larger stab wound or chop off limbs, giving them less chance to kill you before their wound kills them.

|

|

|

|

ammo mammal posted:Are there any movies or shows with accurate depictions of medieval combat? A few have made token efforts. Ironclad with James Purefoy uses half-swording (where you grip the blade with one hand to use the sword as a spear) at one stage and a mordhau (where you hold the sword by the blade and use the handle as a club), and has armour actually make a difference when hit a few times. However, the bulk of the fighting is clearly not done with historical techniques. Which might not be entirely unrealistic (no one has perfect form in a real fight). Kingdom of Heaven has a scene where Balian uses posta de falcone or a Vom Tag (overhead stance), although Godfrey's advice to "never use a low guard" is inaccurate and a bad idea. It also shows armour actually making a difference. Those are about as good as it gets. The bar is pretty low. ookuwagata posted:In most museums I've seen with displays on Medieval and Renaissance armor, you see a lot of ornately designed parade and festival armor, which while impressive looking, doesn't seem terribly practical for actual combat, (the giant protruding animal or monster faces from the faceplates of grotesque armor, for example). What would an upper-class (who could afford to buy custom-made armor) wear to a real battle, and how would the decorative details differ from the armor for show? It depends a lot on the period. Armour design progressed a lot, and most of the decorations were actually defensive features as well. I will give you examples: Transitional armour from around the 1350s:  This is called transitional because it is during a transition between mail armour and plate armour, so it is somewhere in-between. That canvas-looking apron actually has metal plates bolted onto the inside. Decorations for the wealthy are likely to be such things as a velvet cover for the coat-of-plates, or gilt & latten for the studs sticking out of the front. However, a knight might also just wear a surcoat over the top. Decorations are pretty limited at this point. Now for a fairly decorated suit of plate armour from maybe 1380-1420:   The gold or brass trim around the edges of the plates is actually quite ornate by these standards. The full mail shirt is still needed at this point, since the breastplate is fairly limited in coverage. Plainer examples will just miss out the gold trim. However, that would be just fine as a field armour. A later Milanese plate armour from around 1450-1500:  Not many examples of decoration, although imported Milanese armour is a big enough symbol as it is. A decorated German gothic armour from 1450-1500:  Gold trim. The fluting looks decorative, and you might see it on more armour, but those beautiful looking ridges are actually to reinforce the steel. Think of I-beams, the shape is supposed to give structural strength. This allows you to get similar results without making the armour as thick all the way across (saving weight). The pointed shoes are intended only for horseback combat. A later Maximilian (German) armour from around 1500 and later:  Again, more fluting. This was intended not as an upgrade from earlier armours, but to emulate the fashionable clothing at the time, which tended towards pleated looks. An English armour from around 1590:  These were Royal Armours, Queen Elizabeth would award licenses to nobles allowing them to have splendidly decorated suits of armour. This has black-oxide which may or may not help prevent rust, and it is also gilt with a thin layer of gold. This would still be a fairly functional fighting armour. Metropolitan Museum of Art has a good resource on the subject here: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dect/hd_dect.htm Generally, battlefield armour treated decorations as superfluous, though. The stuff is beautiful enough without the extra help. The main rule is practical armour for a real battle clearly looks like armour. If it looks like anything else (most faces for example, or a lion's head, a beard etc) then it is probably parade or ceremonial armour. Another thing is parade armour could often be heavier, it might be bulkier or the body shape is blocky enough to make the arms look as though the shoulders are constantly drawn back. Parade armours typically show more engraving, enamelling, stamped or pressed patterns, cutting into the edges of the plates. The main warning sign of a parade armour is anything that compromises the shape. Being rounded provides structural strength, which is one reason early breastplates could be pot-bellied, since it was a strong shape and the bulbous shape was a glancing surface to make weapons skim off without a solid hit. Others would be pigeon breasted with a point at the front, again to make sure an attack from the front would glance off. Railtus fucked around with this message at 05:50 on Jan 26, 2013 |

|

|

|

space pope posted:Some scholars have argued that French did not become the national language until after WWI and that a lot of regional dialects like Occitan persisted until then. Although semi-fictional The Life of Simple Man shows that in many areas there was little if any sense of being "French." Frankish is a little bit broader than French. 12th century texts like Gesta Francorum or Historia Francorum were not shy about referring to people from all over the Kingdom of France (and a bit beyond) collectively as Franks or Frankish. It also included parts of Germany, but it was distinct from other ethnic groups like the Lombards or Saxons. Railtus fucked around with this message at 05:25 on Jan 26, 2013 |

|

|

|

Sevron posted:Speaking of accurate sword fighting, what do you think of this project? http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/260688528/clang CLANG sounds excellent! I have seen beautiful motion capture in Knights of the Temple: Infernal Crusade (although not the first one). I would really like to see a CLANG based fighting system in a game. I really loved the sword-armlock they showed. Kaal posted:Fantastic thread Railtus. I was wondering what you thought of some of the ideas that this guy comes up with in his video series, for example his theories about how pikes were used in the renaissance period: Thank you for the compliment! I really like his videos in general, I am considering making similar videos when I get comfortable with the technology. I think he normally makes good points, he is intelligent, entertaining, he looks at things from a realistic angle. You have probably guessed by now that I disagree with him about pikes. Pikes did clash and there was carnage. Sources refer to it as Bad War. The Swiss used extremely aggressive tactics, so did the Scots. There are occasions when formations of knights charged all the way through a Swiss pike block and came out the other side (and the Swiss reformed!). What I would do if back in the medieval age is find a monastery. I know they were the social support systems to the poor, I know they valued literacy and education, and they would be the best place for a modern man to survive while adjusting to the new environment and also find a way to apply his knowledge. cargo cult posted:I haven't even made it through the OP yet, but thank you, just thank you. You’re welcome. Pimpmust posted:You brought up the Gambeson, but whenever someone talks about this era it's always about Chainmail/Plate (Knights) vs "Leather Armour" (which every fantasy/RPG every seem to mimmick). Cloth armour was worn by virtually everyone in battle. Even the guys wearing other armour had relatively thin cloth armour as well. It cushioned the armour so it does not chafe, acts as a shock absorber for blows that struck the armour. Another thing was it often had cords on to help attach plates on so the weight of the armour is spread out across the body more easily. Crusader knights were noted by Baha al-Din to wear a vest of felt and a coat of mail so dense and strong that Saracen arrows made no impression upon them. One reason for this is the arrows that worked well against mail (narrow spike-like arrows) were very different to the arrows that worked well against dense fabric (broad cutting-head arrows). By combining mail with padding, neither arrow gest through. Thicker gambesons would be worn by anyone who could not afford metal armour. Sometimes “armour of jerkin” is mentioned, although I expect that to be padded rather than leather. I have worn an arming coat, and the amazing thing is how well it breathes, so on a hot day it actually felt quite cool. I have tried stabbing through the armour with household knives and stuff, though with no one inside it at the time (may affect results), and while I scratched up the fabric a little I did not pierce through. Main advantages are that it was fairly effective armour. It could work quite well against dull blades, although a sharp blade can slice through very easily. This means if the opponent’s sword or “knife” gets nicked or damaged in the fighting that armour will save you, and depending on the spearhead or arrowhead the armour would stop you being skewered. I am not sure how it would perform against maces or warhammers though. Disadvantage is it is ablative. Arrows stick in and tear into it. Slashes that fail to get through will leave gashes that would be vulnerable to the next attack, and the next, etc. Thicker padding could be only slightly lighter than metal armours, and relying on thickness can give the padding a bulk that metal armours do not have. Morholt posted:Crossposting some questions I asked in the general Military History thread. Both forces would be mostly professional warriors, but knights are unlikely. At Grunwald/Tannenburg, one side was the Teutonic Knights, and their armies were certainly not mainly composed of knights. Looking at the casualty figures will tell you that – 8000 dead for the Order, including 200-400 knights. To be honest I doubt the Teutonic Knights ever had around 8000 knights. Another example is either Mohi or Legnica (I cannot remember off the top of my head), when the Templars lost 500 men, including 3 knights, 2 serjeants and 9 brothers. If we interpret knights, serjeants and brothers all as heavy cavalry, that is still only 14 out of 500. That said, it should be noted that the armies that met the Mongols in Poland and Hungary were some of the most slipshod rabble possible. Knightly units, called Lances Fournies, or Gleven, were more likely. These were units consisting of a knight, a secondary horseman, and an archer. Those units would make a good chunk of the forces. Then add militias. Then add mercenary companies. I doubt knights vs knights would resemble duels or pushing matches, although I am not entirely sure how to describe it. Personally I think it depends on which formation got the worst of the lance charge, and then that determined which side was more likely to get mobbed. The only reference I have to knights trampling their own men was at Crecy, when the Genoese crossbowmen mercenaries retreated. I might find other examples if I looked but I think that was just the French being very disorganised at the time. By 1410 there was definitely tactical control. The position on the hill allows the commanders to see how the battle was progressing from above and know where to commit reserves, or where to concentrate archery support and artillery. A problem did exist of calling back men once they were committed, and there were cases of cavalry chasing off the enemy for miles and coming back to find the battle lost. How well a commander had tactical control could dictate the result of the battle; the Scottish won Bannockburn because they had greater tactical control of their schilltroms, able to deploy and attack faster than the English could adjust (read: pull the knights back and let the archers pincussion them). Artillery in the 15th century was certainly common enough to be of importance. The Hussites used it to good effect from the Laager or wagon-forts. Artillery trains were brought at Barnet, and the Yorkists stayed quiet when Warwick bombarded the wrong location, which tells me the effects of having artillery aimed at them were taken seriously. In my mind, the advantage of artillery is you can force the enemy to move; holding position under a sustained artillery barrage is going to get your army shot to pieces. That is why I would expect artillery rather than handguns, apparently the Teutons wanted to provoke the Polish-Lithuanian forces into advancing, rather than trying to chase them. A Buttery Pastry posted:The Franks are of course also a group Germanic invaders, so confusing them with the later French identity might be a mistake. The Langobards/Lombards were as well, but were likewise assimilated into the local population. That both grups placed themselves as the ruling class of an ethnically different population probably makes it even harder to figure out identities I suppose, as the ruling classes have a tendency to not care particularly about anyone but themselves. Trying to assign a modern identity to medieval people is never going to be a perfect fit. The Franks are part of French history but not all French history is Frankish. Inventors might run into trouble from the guild system, which was eager to preserve trade secrets. That interfered with the spread of technology and invention. Another thing is a predominantly rural economy gave many people very limited opportunity to invent, particularly when we have a harvest to bring in. However, I would say to the educated social class with financial backing, medieval times were fairly open to science, discovery and learning more about the natural world.

|

|

|

|

Morholt posted:Thank you for your answers. These two pages both mention the Order knights trampling their own men as they were being routed by the Lithuanians at the opening stage of the battle. Especially in the first one it seems like an attempt at vilifying the Teutons, which is why I asked. Vilifying makes a lot of sense. The first source says the Germans had the best field leaders in the world, if that was true then such poor discipline would be very unlikely. Running down their own men would also waste the force of their charge, and I think the knights would have known that. All the knights would need to do to avoid trampling their own men is to form wedges before charging, which would allow the infantry to scatter safely. Again I think that would be very easy to manage if the Teutonic field leaders were so impressive. Overall, I would say the first source is unreliable in general. By 1410 “massive plates” would describe the German armour far more than it would the Polish/Lithuanian armour. Germany, particularly Augsburg (along with Milan as an independent city state) more or less pioneered plate armour in Europe. In fact, East Europe was the place most likely to use mail-based ‘bechter’ armours which integrate mail with rectangular plates. Grand Master Ulrich “who always underestimated the Poles and Lithuanians” is clearly not the subject of an attempt at being impartial. The second page shows much better scholarship, it identifies patterns in the sources and it talks about possible interpretations and so on. It also seems intended for relatively light reading, rather than delving into the sources with any detailed analysis. A Buttery Pastry posted:That's what I figured, since they did invent some cool stuff in the period. It's not like the "Renaissance" would have worked if people from the middle ages hadn't invented the tools and thinking they needed to do their thing. Yes, although the Renaissance might be overstated historiographically. Some food for thought to throw out there: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vufba_ZcoR0

|

|

|

|

Third Murderer posted:I've done some amateur blacksmithing and I thought I'd say something about this. Pattern welding is done by layering different types of steel and then messing around with the layers by twisting or cutting the resulting chunk of metal. You apply an etching chemical after the piece is finished to make the different types of steel stand out (since they will etch at different rates). The idea that metal made this way is superior in some way is a little spurious - I expect it's a myth. Pattern welding is decorative, although it can indeed be used on a functional blade or other tool. It depends on the quality of the metal you work with. Messing about with layers is helpful if working with poor metals, such as an uneven carbon distribution. By spreading the carbon across layers you can make sure that a sword does not have too much carbon in one area (meaning a brittle spot) and too little carbon in another (a soft spot), to ensure a more consistent quality to the steel. However, once you have the metalworking technology to produce homogenous steel all that becomes unnecessary and a waste of extra effort. Overall, it is not superior, it was just an earlier, more labour-intensive method of compensating for limited metallurgy. Around 600-1200 it was the main type of sword in use, but during the later half of the medieval period forge-folded or pattern-welded swords were considered medium quality, and the best swords were the ones made of homogenous steel. Railtus fucked around with this message at 19:53 on Jan 26, 2013 |

|

|

|

EvanSchenck posted:I had a practical question about armor. Did soldiers and knights wear it throughout the day while they were on campaign, or did they carry it as baggage and put it on before the fight? If they were in a situation where their enemy was known to be in the vicinity, would they sleep in their armor if they suspected a surprise attack at dawn or something like that? Both. There were cases of soldiers wearing armour all the time, particularly with groups like the Landsknecht, who seemed to ditch leg-armour because it was a chore for marching. However, there was also a case of a Duke at the Battle of Azincourt not arriving in armour, and since he tried to armour up quickly he was missing out things that identified him as a Duke – which led to him being killed rather than captured. I can’t remember his name, however. Sleeping in armour depends on the armour. Sleeping in mail or a gambeson is possible; I think it happened during the Crusades. Sleeping in full plate armour would be very difficult.

|

|

|

|

Kaal posted:I am super enjoying this video series. World History, Literature, Ecology, Biology, all wrapped up in pretty little videos! The one about the Crusades is hilarious.

|

|

|

|

Third Murderer posted:Anyway, I have an actual question. How common was it for the western European kingdoms to claim to be inheritors of Rome? I know Charlemagne was crowned emperor, probably to the annoyance of the Roman emperor over in Constantinople. I would think that, after hundreds of years of Roman rule in places like France and Iberia, that linking your kingdom to the Empire might have been a good way to claim legitimacy? The main one was Germany, despite being perhaps the one nation with the least right to make the claim (the Holy Roman Empire was more or less the territory in Europe that the Romans didn’t conquer). What happened was Charlemagne’s Carolingian Empire split on his death into the Kingdom of the Franks (aka: Kingdom of France) and the Kingdom of the Romans (aka: Holy Roman Empire). Kaiser is essentially the Germanic form of Caesar. Apparently East European empires used the term Tsar for it, although without as strong a Roman connotation. I have heard that the Russian Tsars were the eventual heirs to the Byzantine/Roman Empire, but I have not studied that. After the sack of Constantinople a group of Crusaders formed the Latin Empire to try to claim the title of successor to the Romans. Ultimately claims of being the Romans tended not to go anywhere. Germany was largely thought of as the Empire rather than as being particularly Roman. The Byzantine Romans were frequently called Empire of the Greeks or of the Hellenes, though. A complicated factor is that the Pope had already crowned Charlemagne the “King of the Romans”. So anyone else trying to link their kingdom to the Roman Empire had to either claim a link to Charlemagne or dispute the legitimacy of Charlemagne’s coronation. This put people off. Pfirti86 posted:I think the coolest part of medieval history is the stuff that was going down between 1000-1300 in Germany. And like no one ever talks about it. Was Otto IV really beaten to death by his priests? I guess that's what you get for being a Welf! Do not forget, he asked his priests to beat him to death. Nothing springs to mind to say about Italy, although I might add some comment if something reminds me of them. Sicily was apparently Muslim lands for a while, and then Norman lands after that. Kaal posted:I mean, pretty much everyone called themselves Tsar of this or Kaiser of that. The one exception might be England, but on the other hand their kings did pretty much declare themselves to be the pope. The English issue about being head of the church actually goes back to King John Lackland/Softsword aka King John the Completely useless (although the only King John England had). King John essentially seized papal lands in England and the lands of the Archbishop of Canterbury, which resulted in an interdict being placed on England in 1208. An interdict is essentially the church going on strike. Baptisms were allowed, confession and absolution for the dying was allowed. But no marriages, no funerals, maybe even no Mass. Lay people had very limited access to the churches in England etc. Eventually, King John was frightened by the suggestion that the Pope was supporting potential invasions of England that he made England a vassal of the Pope. So when the later troubles with Henry VIII began, remember that England was actually Papal property at the time.

|

|

|

|

Lacklustre Hero posted:How cool was El Cid El Cid is very celebrated, he was an extremely successful military commander and a champion of Prince Sancho. Unfortunately, he made his career partly against Sancho’s brothers, which meant that after Sancho died without heir El Cid lost his status and eventually went into exile. Until King Alfonso started losing and needed El Cid’s help. El Cid was loyal to Sancho, however, not necessarily the crown or the family. Particularly as El Cid had been fighting the family for Sancho. Instead of immediately coming to the rescue El Cid started seeing the conflict as an opportunity to carve up some more land for himself. Valencia. Which he succeeded in, officially one of Alfonso’s servants but functionally independent. The city and his administration were tolerant of both Christians and Muslims, with administrators and soldiers of both faiths. That he commanded the loyalty of both religions is a sign that he probably was pretty cool. Another cool aspect was he was very inclusive in his leadership; he would discuss tactics with his troops and accept suggestions. Overall, El Cid was the ideal of knighthood. A valiant champion, an inspiring leader, fair-minded enough to win the loyalty of Christian and Muslim alike, he loved his horse (kind to animals is cool to me) and was a keen tactician. You do not get remembered in history books as simply “The Lord” without some level of awesomeness. AlphaDog posted:Railtus, you said you got to slash at a gambeson without a person inside it - did you place it over something? Trying to cut at things when they're just hanging there is significantly harder than if they have something solid behind them. We did a test with an old mail shirt, and couldn't break it when it was hanging up. As soon as we laid it over a watermelon, the first blow split rings and left a hole (and wrecked the melon). With padding between it and a melon, it still wrecked the melon, but the padding had enough give that the rings didn't split. I just had my arming coat hanging. It was a quick demonstration to my mother’s-fiance’s-granddaughter. INTJ Mastermind posted:How common was differential hardening in European swordsmithing? The Japanese figured it out with their swords - getting a very hard (holds a sharper edge) yet brittle edge section that's backed by a softer and more resilient core. Hard edges with softer cores were standard, the edge hardest nearer the ‘sweet spot’ (part of the blade was most intended to cut with) and softest near the base of the blade (more likely to defend with). This tells me it was mostly strategically chosen hardness levels. However, they typically used different methods to the Japanese. Rather than using clay as a form of insulation, they would use differential tempering. Low quality swords might just have carburised edges, which means the edges would harden more than the core during quenching. Some research on blade hardness: http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_bladehardness.html All of the swords they examined had differential hardness contents, which seems to be the pattern with studies into this. That does not tell me whether all European swords had it or whether they just picked the ones that did for the studies. Since even the lowest quality swords had harder edges and softer cores, I would expect it was commonplace. It was an alternative form of differential hardening, although it produced the desired effect. Differential hardening appeared to be present on swords as early as the Nydam ship (3rd-4thC). Arabic accounts of western swords seem to suggest both flexibility and hardness. Al-Kindi describes both iron and steel used in European swords. Ibn Miskawaih reports raids of Viking graves to find high-quality swords. Nasirredin al-Tusi refers to western swords as extremely flexible and so hard they could hack iron nails. I do not think they differentially hardened it to the same degree as katana, but I think that was a conscious design choice. EDIT: I have heard some at SwordForum say "occasionally" differentially hardened, although that could mean more than one thing - it could mean other swords have uniform hardness, or it could refer to differential hardening as a technique instead of differential tempering or carburisation (other ways to have a hard edge and soft core). However, all research into the hardness of western swords throughout the blade seems to suggest strategically distributed hardness and none of the research I am familiar with has ever provided evidence of a sword with uniform hardness content. So it could just be that these studies have simply not looked at the ones without differential hardening/tempering/carburisation. A Buttery Pastry posted:Ivan III married the niece of the last two Eastern Roman Emperors, Sophia Palaiologina (AKA Princess Zoe). Through her, the Tsars claimed to be the Third Rome (though they're not the only ones), and got it into their heads that they should retake the Second Rome (Constantinople) which kind of set the tone for Russia for the next 450 years. Thanks for the information! Railtus fucked around with this message at 01:50 on Jan 28, 2013 |

|

|

|

SoldadoDeTone posted:As far as I recall, the Russian Tsar, Ivan III at some point married "the last princess of Byzantium." Basically, Russia sought to obtain the title of Rome and found a woman who may or may not have actually been related to the royal family of the Byzantines. She was reputedly the niece of Constantine XI. Moscow itself was referred to as "the Third Rome." There is a famous quote by one of the Tsars at the time that I cannot correctly attribute, but it was something along the lines of "Moscow is the Third Rome, and it will never fall." Thanks, that is really helpful.

|

|

|

|