|

Buried alive posted:I've sometimes heard that english/western European weapons were essentially big metal clubs in the area of 10-20 lbs. Are there any surviving historical examples of those that were intended for combat? Or is that more from the mistaken attitude that katana > all. Probably none. There were the occasional parade/ceremonial sword that weighed above 8 lbs, but the only example I can think of is very much disputed, Piers Gerlofs Donia was a huge man said to be able to bend coins with his thumb, index & middle fingers, and he had a sword that weighed 14 lbs and was 7 foot long – but even then we do not know if that was his fighting sword or not. I am leaning towards not, because he acquired it from plunder, so it was not made specifically for him. Generally a longsword would weigh around 3 lbs (with some heavier war swords around 4 or 5 lbs), a pollaxe or halberd might weigh 7 or 8 lbs. In fact, according to Tsurugu-Bashi Kendo Kai, knightly swords were typically lighter than katana of similar size. Obdicut posted:Did the use of war-dogs continue during the Medieval period? I know that the use of them by the Romans and the pre-Roman Britons was mainly in scouting and guard duty, but they did actually use them it pitched battles too. War dogs certainly saw some use, I am not sure how deliberate it is or not. But at Agincourt, Sir Peers Leigh was wounded early on, and he was saved from capture because his mastiff fought off the French knights. We do not seem to have large waves of war dogs though, except for maybe very early medieval (kind of more post-Roman) or the conquistadores against Native Americans (and I am not sure that was entirely battlefield use). War horses were certainly trained heavily, since a war horse was expensive. Some were even trained specifically to kick forward while the knight on top was fighting. So the answer is probably yes, but the sources I am familiar with do not mention the desensitisation specifically. Nektu posted:If you can hit him, he can hit you. Evading attacks for a prolonged time is hard to say the least and incredibly error prone (probably would be your last error). Forgive me, but you appear to be responding to the exact opposite of the part of my post that you quoted. Unless you are actually agreeing with me, but the phrase “the big problem with the way you imagine it" kind of implies that you have gotten the wrong impression, because your criticism matches the opposite of what I describe. INTJ Mastermind posted:When and why did it become unpopular for (civilian) men to walk down the street armed with a sword or dagger? About 1800-1850, although the swords popular to wear in public were becoming less threatening before then. By 1400 a knightly sword or longsword would be common, by 1600 a long rapier was in style, by 1700-1800 you get smallswords or sword canes, and then specialised duelling swords or epees designed to draw blood without being lethal. The reason for the change was partly convenience. A longer blade was kind of inconvenient to carry around if you were not planning on using it. Later on duelling became more formalised and less accepted, and it was more likely to involve pistols etc. Under those conditions, there is less of a reasonable case for carrying bladed weapons in public. Railtus fucked around with this message at 21:42 on Feb 6, 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ May 9, 2024 17:07 |

|

Nektu posted:Maybe? Lets see... I see what you mean, thanks for clarifying. To make sure I have not confused other readers I should clarify as well. By striking from a safe angle I was referring to aggressively shutting down their options for attack, such as with the bind (restricting their sword for the benefit of those who do not study swordsmanship) or moving behind a path of safety created by your attack so that the angles they can strike from their current position are already covered. The idea is it is preferable to stop them from throwing their attack in the first place than to try stopping it once it has begun.

|

|

|

|

Vigilance posted:How much of an issue would fatigue be in battles? It must be loving exhausting battling for a while in heavy armor, even if you're in great shape and used to it. I imagine it was brutal on the horses, too. It was very much an issue, it was also managed. I think Emperor Maximilian wrote down about the need to rotate your troops through the ranks in battle so that they could rest, and even have a barrel of water at hand for each 8 men or 8 ranks, I do not remember which. People in armour do fatigue a little more quickly, but not that much more quickly than an unarmoured man fighting. Armoured combat certainly stressed economy of movement to avoid becoming tired. Still, you could actually use less energy in armoured combat since you do not have to move as much to defend. Knights would often have more than one horse; one for travel and one for battle or having remounts during combat. Kaal posted:As a counterpoint, this study takes are more critical view on the weight of plate armor. It's worth reading, though I'd note that their 15th century armor was twice as heavy as normal since it was designed to stop bullets and heavy crossbows. Not only is their armour much heavier than normal (and the quote indicates the people conducting the study are unaware of that), they made another major mistake here. quote:The breast and back plates of the medieval armour also affected breathing: instead of being able to take long, deep breaths while they worked up a sweat, the volunteers were forced to take frequent, shallow breaths, and this too used up more energy. I asked Dierk Hagedorn (head longsword instructor at Hammaborg) about this, and he never experienced anything of this nature. No one else I know who owns armour found this problem either with the suits they wear. To me it seems likely that the armour the BBC study used armour that did not fit the wearer, which is going to affect the amount of energy used significantly.

|

|

|

|

Essay is finished. I have a dissertation to work on but this should be making a fairly constant pace.Rodrigo Diaz posted:This is old but It depends what you view as “made his career.” By 1188 William Marshal was 41 years old, granted a large estate, and in royal favour. Most of the parts of his life I find interesting came later, but this was fairly late into his life and it was his success in tournaments more than his success in battles that got him there. MoraleHazard posted:

You’re welcome. Thank Wiggy Marie, she convinced me to start this thread. Overall, not true. The average life-expectancy was fairly low, although this was mostly caused by infant mortality. Then we get the Black Death after 1350. Then we get wars. This means we cannot take the average lifespan from birth at face value. At least in England, people seemed to expect to live into their 50s & 60s. Bishop Isadore (from Spain, 7thC) wrote that “seniority” was from 50-70 and “old age” was 70 and up. People did die younger quite a lot, but the interesting thing is life expectancies seemed to get longer as people got older. What that indicates is people were more likely to die young, which was what brought the average age down. A source on the subject: http://sirguillaume.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Old_Age-Height-Nutrition.pdf Some notes I made reading through it: English medieval landowners expected to live into their 50s & 60s. 20% of the young adult population (20 years old) lived to 60. 50% of those who reached 60 reached 70. 50% of all babies died before age 25. I hope that helps! Wiggy Marie posted:This is more related to the culture: how much of a role did superstitions and folklore actually play in medieval life? There's a perception that diseases = possessions/demons/spirits, etc., and of course there's tons of documents with "monsters" (large fish) and such from the time. Is there any way of knowing how much stock was put into these? Good question! The main obstacle with examining the influence of superstition is that much of the information out there on superstitions tended to be from the historiographical “dark ages” – essentially the older school of historians that portrayed the medieval period as backwards and ignorant, which seems to be generally unreliable scholarship. That said, there were certainly areas where superstition had influence. Trial by Combat was one example, since the expectation was that the rightness of one’s cause would help one in the fight. Ish. There were a lot of examples of people questioning it with very non-superstitious views. One Pope wrote to the Teutonic Knights telling them to stop imposing trial by combat on people they converted. Kleines Kaiserrecht openly stated that innocent men were wrongfully convicted for being physically weak, etc. It is more likely the superstition element was really just a convenient excuse for retaining a pre-medieval custom of single combat. Trial by Ordeal happened, although interestingly enough the Church was opposed to it. Priests were forbidden to cooperate since the Fourth Laterin Council (1215), although that also implies that priests needed to be forbidden from going along with it. For much of the medieval period, witch-hunting was outlawed – in the Lombard Code of 643, in the 794 Council of Frankfurt, the Bishop of Worms around 1020 was writing against the superstitious belief in magical potions, magic, curses, night flying etc. We could use this to argue that the sources were clearly anti-superstition… but there was clearly enough superstition around for people to go to the trouble of writing against it. Otherwise it would be like someone writing about where they stand on the issue of albino octopuses named Jerry. Then around 1320 the Church made magic-use a punishable offence, although most Inquisitors did not take it seriously. There were cases of accused witches in Milan (1380s onwards) who confessed to having participated in white magic. The Inquisitors were not sure what to do – the women confessed, but they clearly were not harming anyone – the Inquisitors just sent them on their way with a few words about being more careful around superstitions. I could say more on this and the development of witch trials, but it might be getting off-topic. My overall conclusion is that superstition was clearly present and influential enough for the Church to spend a lot of time and effort trying to fight it. One questionable source was Kitab al-I’tibar, an Arabic text by Usamah Ibn-Munquidh, who describes a Frankish physician diagnosing a woman as possessed by a demon and cutting a cross into her skull (which killed her). But, Kitab al-I’tibar is a sort of poem/tale where the author was expected to take liberties with the facts in order to tell a more compelling or educating tale. One interesting belief was in the healing power of relics, which follows my favourite trend in medieval history – when they get things right for the wrong reasons. People would travel to a holy site in the hopes of receiving healing upon completing their pilgrimage. This means holy sites would have large numbers of sick people travelling there. So the church set up hospitals in those locations, meaning that people would get at least some healing or treatment after all. Beneath this avalanche of examples I get the impression that there was not necessarily a distinction drawn between the magical and the mundane. Medieval bestiaries would feature a hippopotamus and a cockatrice (rooster-snake-dragon that turned people to stone) without explicitly viewing one as magical and another as non-magical. This is a very rambling response but the overall theme is “it depends.” :P My overall theme is enough people put stock into superstition for other people to be complaining about superstitious people.

|

|

|

|

Xiahou Dun posted:Any good resources on non-ecclesiastical Medieval music? I do a little, but most of it's really late. Interesting question. My advice is to look for work by individual composers. James. J. Wilhelm had a book called Lyrics of the Middle Ages, but I have no idea how good it is. Bernart de Ventadorn has music intact for at least 18 of his poems. Apparently Trouvere music tended to survive quite well. Perotin from around 1200 wrote the Allelulia Nativatis, although that might still fall under church music. Gaucelm Faidit has 14 melodies surviving - http://www.trobar.org/troubadours/gaucelm_faidit/ Again, music is outside my area of expertise, but hopefully those name-drops might give you something to work with. I have never heard of Corvus Corax before, but I love ravens and crows in general. Their music is certainly pleasant to listen to, and from what I can tell it sounds like they were using the same musical instruments as back then – so I think with those two criteria they are going to produce something fairly similar to medieval music. monkeyharness posted:Thanks for the excellent thread. In reading through it, I think it kind of speaks a bit to a couple of question that I have always wondered about when watching movies/documentaries on warfare during the Medieval period: How did anyone walk away from a Medieval battle without some form of crazy grievous injury? At the risk of sounding flippant, one way was winning, another was surrendering (not always reliable) and a third was running away. Although this is more for knights than the footmen, armour worked really well. A good suit of mail was very reliable, there were stories of Crusaders on foot covered with arrows and seeming completely unaffected. A coat-of-plates was very reliable too, able to stop a couched lance fitted with a graper. Essentially most armour used at the time would stop most hand-held weapons – at least initially. Once you got stunned you were more vulnerable. However, it is important because generally the guys with the least protection were more likely to be archers or in the back ranks or otherwise less exposed to danger. Late-period pike phalanxes seemed to have their best armoured troops at the front, and early period formations such as the Boar’s Snout seemed to recommend having the guys at the point of the wedge be the most well-armoured. To a degree you are right. Re-enactors doing shield walls and other competitive battle simulations found that most people never saw the guy that scored a killing blow on them. My guess is that both individual warriors and their commanders actively avoided the kind of exhausting, confusing mass of bodies you describe – precisely because it was so dangerous. A good case for it is made by I-Clausewitz; http://l-clausewitz.livejournal.com/141128.html Essentially formations staying in good order was what stopped the swirling mass of confusion and death. If one group lost cohesion first, that would be the group that started taking lots of casualties, and the carnage that followed would be fairly one-sided. The only times both sides would end up in a swirling mass would be if both groups lost cohesion at the same time, which was more common post-1500 during pike-and-shot, referred to as ‘Bad War’. As opposed to the nice friendly kind of war. Another thing to consider is fear. Quite a lot of people would hold back from the fight, there were complaints about soldiers “fencing” with the pike, which is standing at full pike length and just poking at each other with neither side continuing their advance more aggressively. Battlefield medicine, from what I could tell, was moderately advanced. I did find this - http://www.strangelove.net/~kieser/Medicine/military.html - which I find fairly trustworthy because it openly points out the limitations of its own information. GyverMac posted:What would be the best weapon (non-ranged) to give a mass of fairly untrained people? A shield and a spear? Either spear and shield or pike. Spear and shield was more common in the earlier stages, pikes were more common later on. What was popular was reinforcing pike phalanxes with dismounted men-at-arms (knights fighting on foot) so that you had the skilled men there for when the enemy did get close. From what I can tell, halberds tended to be more popular with skilled troops, although that could be more related to cost than to usefulness. The Swiss Reislaufer tended to have a core of halberdiers in their pike squares who were also well-armoured men. Among Landsknecht the guys with halberds were most often Doppelsoldners (double-pay men). Halberds can be pretty unwieldy if you do not know what you are doing, I think you would need training to use the axe-part effectively, particularly at closer range. On the other hand, just because someone lacks military training does not mean they are necessarily unskilled in the movements needed to use a halberd or other polearm effectively. One trick that worked quite well were weapons based around farm tools. The English billhook was a weaponised version of a gardening tool. Occasionally grain flails were modified to become weapons. These could help mitigate the level of training required.  bewbies posted:Terry Jones' Medieval Lives did a great thing on minstrels/jongleurs/troubadors. The "Song of Roland" that the guy performs is probably very close to what the real thing sounded like. Anne Whateley posted:I'm not sure. I watched it awhile back, so I don't remember specific quibbles, but I remember being irritated a lot. Rodrigo Diaz posted:Maybe not past the fifth grade for people who like history but some dude came into this thread asking of medieval people stank so bad we'd pass out were we to meet one. Some things are vexingly persistent, like constant witch-burning, 20 pound swords, the all-powerful longbow, medieval people being inherently stupid, etc. and Medieval Lives goes a little way to correcting that. Terry Jones is very fond of alternate takes on ‘common knowledge’. In some regards this is a good thing; he shows that peasants were not virtual slaves, on the other hand he gave a very one-sided account of the knight – John Hawkwood and the White Company was not really the best example of knightly conduct. I think he could be far more balanced in his consideration of the evidence. A good criticism of Jones’ analysis of Chaucer’s Knight is here - http://www.ueharlax.ac.uk/academics/research/documents/FiloGina.pdf

|

|

|

|

EvanSchenck posted:The first part of the answer is that masses of untrained people were not a common sight on the medieval battlefield. It's a myth. Battle was the domain of military aristocracy, and most battles were clashes between well-equipped professional soldiers. Peasants were often caught up in wars, usually as passive observers or as victims of raiding and "foraging." This was partly because wars were mostly fought to resolve disagreements between rival kings or lords, to which peasants were not party; mostly it was because even a small force of professionals could overpower a huge mob. To give a few examples, the Battle of Visby was depressingly one-sided, even though the peasants had some armour and equipment. Another thing would be the 'success' of the chevauchee tactics during the Hundred Years War (well, they succeeded in looting and burning villages, but failed at their goal of winning the hearts and minds of the people whose homes they just burned down).

|

|

|

|

Rodrigo Diaz posted:"Winning the hearts and minds of the people" was not a primary goal of the chevauchée, at least not in the campaigns of Edward III or his sons. Speaking strategically their chief purpose was to draw the French into unfavourable battle-- Crécy and Poitiers being the most famous examples from this period. They also served to help pay for the armies and of course to supply them, but Clifford Rogers has done a pretty good job of showing that their chief purpose was to provoke the Valois onto the field. I am being a little ironic in my description; I figured I did not have to repeat the more nuanced commentary I made in earlier posts. Thanks for the source though, is the work by Clifford Rogers Wars of Edward III: Sources & Interpretations by any chance? I would be surprised to hear Crecy used as an example of drawing the French into an unfavourable battle. On paper, Crecy looked like it was unfavourable for the English. If the French had not made major mistakes like attacking without having rested from the march or forcing their crossbowmen to leave their pavises in the baggage train I would have expected the French to have the advantage. On the other hand, Poitiers does fit that description better.

|

|

|

|

Rodrigo Diaz posted:I was actually thinking of War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327–1360, though Wars of Edward III would certainly be a useful companion. Thanks. I had been thinking about this a little more and the chevuauchee also makes a fairly decent Xanatos Gambit ( http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/XanatosGambit ) since it becomes a lose-lose situation for the French. Either the French overextended themselves trying to meet the English or they fail to protect their people. (USER WAS PUT ON PROBATION FOR THIS POST)

|

|

|

|

monkeyharness posted:Thanks for the response. What are some of the largest battles that occurred during this time period? You’re welcome. I saw some armour from the Royal Armouries in Leeds, and what is amazing is the attention to detail that goes into it. The fluting on gothic or Maximilian armour was a design feature intended for structural strength. Mail rings were often flattened to increase the surface area of the links (probably so that any strike was spread across multiple rings of mail and therefore having less chance of breaking any of the links) as well as riveted or forge-welded shut to stop weapons forcing open the rings. A general theme with armour is that a blow stopped by armour can still be effective, such as with a pollaxe or warhammer or just the impact of an axe. Or the blow might pierce the armour but their life was still saved by wearing it (such as the coat of plates vs lance or the breastplate vs arrow links below. A good list of examples of how effective mail armour could be is Mail: Unchained by Dan Howard - http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_mail.php An important point is the thickness of the iron wire used in mail varied, so there were lighter versions and heavier versions that obviously varied in their protection. Lighter sets of mail had larger holes, which meant narrow-tipped swords could slip through, and one set of mail can be different to another - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kl-ec6Ub7FM The coat-of-plates resisting a lance was based on this test by Mike Loades, I wonder if using the same foam all three times affected the test though - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJnkH1YXY8E#t=21m34s (starting at 21 minutes 30 seconds if the link is being strange). Another somewhat similar test involving a longbow and a breastplate - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3997HZuWjk

|

|

|

|

Rodrigo Diaz posted:Your comment on the fluting in armour is interesting, because I had always been told that it provided more glancing surfaces, rather than that it made the armour sturdier. It could certainly do both, of course. To confirm what others have said, I have heard the fluting described as resembling corrugated iron or steel I-beams as girders. The other use I heard was the fluting on the surface could act similar to a stop rib, causing blows sliding across the surface of the plates to skim off rather than slide into a vulnerable point. With mail, it is not that rounded cross sections stop the force from being spread out, but the inner diameter you mention is combined by the flattened rings linked together also obstruct the space within that inner diameter, making it more likely that several rings will be in the way of a blow. However, that is pure speculation on my part without any sources to back it up. Also, I love The Knight and the Blast Furance. I highly recommend anyone here check out the previews online. Makrond posted:I've met people who were under the impression that if you used a pole weapon against someone with a sword or an axe they'd just cut clean through it and kill you, but I feel like it would be a struggle even with just a pine shaft, let alone the hardwood shafts everyone was using. Another thing was metal cheeks or langets reinforcing the shaft. AlphaDog posted:Edit: Wasn't one of the functions of the Zweihander to chop through pike shafts? I swear I read that somewhere but I can't find a reference now. There is a 1548 woodcut of the Battle of Kappel showing zweihanders being used against pikes in a way that may suggest hacking at them, although personally I am not that convinced. Another suggestion I have heard is that parrying hooks (the secondary crossguard) could be used to bind several pikes at once and push them aside, creating a breach your side can exploit. On the other hand, that was a later addition to two-handed swords, many bidenhanders or motantes or similar war swords did not have them and they were still semi-popular in pike squares before then. New Coke posted:Was there any kind of analogue to the guerrilla/asymmetrical warfare of today? You mention that hit-and-run tactics were common among professional armies, but was organized resistance to invaders common after the official army had been defeated? You tend not to hear about things like this nowadays, and I can think of a few reasons why that might be, but I'd be interested in hearing whether or not there were instances of that happening, or how common it was. Yes, asymmetric warfare happened, although it does not appear to be common/routine/standard enough to call it an analogue to guerrilla warfare. The main examples I know of was Hungary after the Mongols won the Battle of Mohi in 1241. However, what was more successful was just to bring all the food inside a fortified building (a nearby refuge, monastery or town) and just wait for the enemy to leave, which was more successful for the Hungarians. Most of the places with those defences were able to resist the Mongols. In fact, Hungary tended to be the main place for guerrilla warfare, typically against invasions from the east. I think it did happen occasionally in the Hundred Years War, although it seems to have been rare enough that most people did not have a ‘concept’ of guerrilla warfare, it would just be isolated incidences brought on by exceptional circumstances. Kaal makes excellent points on the subject. Medieval Europe was a very unfriendly place for guerrilla warfare.

|

|

|

|

Vivoviparous posted:Well in the interest of having this wonderful thread not die I will ask some questions. Actually, they’re good questions. Doing a quick read-around, I saw some suggestions here - http://www.richeast.org/htwm/mmed/mmedicine.html - I cannot verify that website but it does cite its sources. They mention Queen Anne’s Lace seeds being used to prevent pregnancy, and more abortion methods. I should note that abortion methods were not all that safe. Until surgical abortions, terminating a pregnancy often led to the dead foetus remaining inside the body. Some herbal remedies are suggested here - http://faculty.bsc.edu/shagen/STUDENT/Joy&Chris/contraset.html - This is also the kind of thing that in England “cunning folk” might do. Again, it lists the sources, but elsewhere it mentions chastity belts, which you should never take at face-value in reference to the medieval period. The evidence for their existence in medieval times was circumstantial at best (Bellifortis sketch 1405, which seems to be a joke) and like many ‘medieval’ torture devices they seem to be mostly Victorian inventions. I like Bernard Cornwell, his writing is fun to read, he does a fair amount of research, and he also makes no secret of when he takes liberties with the facts for the sake of a good story. I greatly enjoyed the Warlord Chronicles (a re-imagining of the King Arthur story based on the early Celtic context), I also absolutely loved Azincourt – Sir John Cornewaille is spectacularly entertaining and I love Hook’s religious experiences. My main criticisms of his writing are that he gets carried away with the subjects of corruption within Christianity (which did happen, but far less than one would think from reading his work) and the mistreatment of women. Flail type weapons were never common, but did gain some popularity during the Hussite Wars. One ordinance from the 1400s in Germany required 3 men out of 20 have flails. They were definitely inconvenient and had serious flaws, although their main strength in my opinion is that many peasants were familiar with using grain flails and so might have an easier time using them. Main-gauche & parrying daggers were generally civilian weapons, although not strictly for duelling. The context they were most likely to be used was an urban street fight or ambush. They were excellent for stabbing when either your swords bound up or when your opponent gets past the point of your sword. Civilian swords tended a little more towards rapiers, which had excellent reach but were far less effective when up-close, so having a short off-hand weapon meant you could deal with that situation quite handily. A pair of identical weapons was very rare, there is mention of a ‘case of rapiers’ in some Italian sources (I think Di Grassi) but these do not appear to be the norm. Generally two full-size weapons are more likely to get in the way of the other, and if you hold a weapon in each hand it is generally preferable for them to be able to do different things and therefore cover each other’s weaknesses. Like the aforementioned rapier & dagger being effective both at long and short reach. Battlefields did not seem to encourage dual-wielding though. Early on weapon-and-shield was most popular, while later two-handed weapons were more the thing. The sword-and-buckler was very popular, for people who wanted to switch from a two-handed weapon (a bow or a pike, for example) to weapon-and-shield quickly once the enemy got close. Occasionally we have references to warriors having multiple single-handed weapons, but it does not say if they were to be used at once. I hope that helps!

|

|

|

|

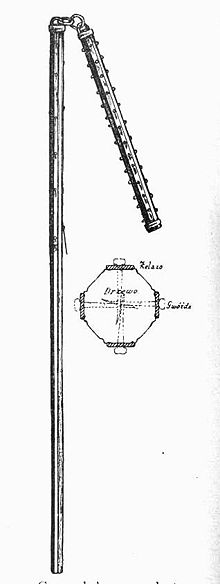

Alien Arcana posted:While we're discussing weapons again, how about hammers? I believe cavalry hammers were a thing, but were they ever in use by infantry? What did they look like? Hammers were definitely in use, I would even say primarily in use by infantry. They were relatively affordable and good anti-armour weapons to stun or slow-down a well armoured opponent. We see them mostly in the 1400s, although quite a few forms were around earlier to lesser degrees. First thing about how hammers looked is they were relatively small. A giant head is not that desirable, partly because of the extra weight and partly because a smaller head concentrate the impact of a blow onto a smaller area (not that you cannot get around the issue with a larger hammer, but the smaller ones make it easier). You see some hammer-heads split into flanges or serrated faces like a meat-tenderiser to further concentrate the force of a blow onto a smaller area. Second thing is the hammerheads were very rarely alone. They would typically be combination weapons with an axe or spearhead attached, in some cases picks. The early versions were just a protrusion on the back of an axe. It gets referred to in Norse sagas as an oxarhammer (axe-hammer) for striking a less lethal blow. Byzantine axes I was researching earlier into the thread sometimes had hammers on the back, etc. How far this was a conscious design to have a hammer head or a by-product of making a strong back so the axe is secure in place I am unsure. Later on you get much more purpose built hammers like many pollaxes, these are still not always or not entirely hammers (generally Europe liked to produce polearms with lots of different ways to kill people), but the role and prominence of the hammer seems to be increasing. Another option was the mauls used by longbowmen, primarily these were tools to drive wooden stakes into the ground, although they also seemed functional as weapons when fighting against people in armour. How far they count is a matter of opinion; I tend to think of them as tools being used as weapons rather than weapons in and of themselves. My image-search is being uncooperative, but they tend to look just like wooden sledgehammers. Railtus fucked around with this message at 23:05 on Feb 19, 2013 |

|

|

|

EvanSchenck posted:You should rehost those pics on imgur or something if you want to post them, else you might get in trouble for leeching bandwidth. Thanks. I tried with mallet, although unfortunately I never got quite what I was after.

|

|

|

|

Frostwerks posted:Did sword and gauntlet ever get used with the gauntlet as both a defensive tool and offhand weapon? I really don't know much about the combat of the era (or hell it may have even been after that or in fact never at all) so I'm probably full of poo poo. Was sword and cloak ever a thing? Overall, sword & gauntlet: no. Sword & cloak: yes. With sword & gauntlet, no fighting text I know of seems to specifically advise the use of both together. You could use the same techniques as single-sword with the other hand empty, but generally if you have access to a gauntlet for your left hand you are probably armoured and so to a degree those techniques would not apply. If you are not in armour, such as in a civilian context or you simply lack the resources, there are clearly much better options such as sword & buckler or sword & dagger. That said, there was some weird thing called a lantern shield, which was a bizarre combination of a shield, a gauntlet, several different long knives and a lamp all at once. Apparently it was supposed to be for a watchman at night. Sword and cloak has references for different times. Rapier and cloak is taught in Spanish rapier fencing, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umKZ-Y4T66Y and Swords & Swordsmen by Mike Loades mentions bronze figurines from Villa Giula with swords and a cloak rolled over their left arm. In later-period fencing, cloaks were great for entangling your opponent's weapon, masking your figure (hold it in front of you they struggle to know where to stab), generally blinding your opponent etc. In the early period sources, one suggestion was you could use the the cloak like loose netting to absorb the energy of a blow or generally protect your forearm (which is viable unless your opponent has a sharp slicing sword) and it can be held in front of the sword handle so your opponent cannot clearly see what your sword-hand is doing. This makes blows more likely to be a surprise.

|

|

|

|

Vivoviparous posted:

Chastity belts were mostly just the Victorians projecting their own insecurities onto earlier societies. Confirmed finds are overwhelmingly nineteenth century, there are rumours of one from the sixteenth century but it is missing, and the Bellifortis sketch was from the fifteenth century. However, medieval documents otherwise do not mention the thing like it was any kind of common practise. If they existed at all in the medieval period they were rare, and generally something not discussed in public, when the medieval world otherwise had some very frank documents about sex and sexuality. Cultural trauma is a new term to me, so it is difficult to comment on. However, I will say the Inquisition would be nowhere near as traumatic as the other examples. Thomas Madden even makes the argument that the Inquisition was a force for good mitigating or reducing the damage done by secular courts - http://old.nationalreview.com/comment/madden200406181026.asp That said, I disagree with his other similar article on the Spanish Inquisition, which contradicts itself. At one stage it says the Spanish Inquisition did not have the power perform executions, then it later states the Spanish Inquisition performed fewer executions than other courts – which would only be a valid point if it had the power. http://www.crisismagazine.com/2011/the-truth-about-the-spanish-inquisition In theory, the Spanish Inquisition was just. Officially they only had jurisdiction over Baptised Christians, so could not persecute Jews or Muslims. In practise things were rather unjust. The Alhambra Decree of 1492 required Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave, then Muslims later. Many chose to stay on the grounds that they had nowhere else to go, but the Inquisition was charged with investigating “false converts”. This was a very unfair situation for the Jewish & Muslim population of Spain. However, the Inquisition also did some good things. They stopped witch hunts, they acted as a control against corruption in the church, they made sure the trials of heresy were based on theology rather than mob rule or lynching. Essentially the point I want to make is the Inquisition seemed to be more of a symptom of cultural trauma rather than a cause. I certainly agree that Cornwell has grown more balanced in his treatment of the church than he once was. Warlord Chronicles was painfully anti-Christian, but Azincourt has both a corrupt priest and a good priest. I have not read most of his recent works though.

|

|

|

|

For anyone interested, take a look at Google Books, Inquisition by Edward Peters. It has a fairly significant preview.Obdicut posted:Suddenly I'm seeing this Madden thing everywhere. It's weird. He's not the most credible professor on this topic-- he did a lot of bizarre press stuff after 9/11, talking about the crusades and how they relate to 9/11. And my dad, who's also a mediavalist, just burst out laughing at the idea that the church was a moderating focus. Or more accurately, how the Crusades did not relate to 9/11; there were strange ideas going on at the time, for example this speech by Bill Clinton: http://ecumene.org/clinton.htm There was also an issue about George Bush using the word “Crusade” to describe America using military force against the Middle East. Kemper Boyd posted:I think the best way to summarize the Inquisition is that they were very fair in carrying out unjust laws, which is kind of a running theme in early modern jurisprudence. For instance, Sweden implemented Mosaic as the criminal code in the 17th century, but the courts never punished the guilty to the full extent of the law. I really like that description. To me the Inquisition was not exactly a good thing, but it was kind in comparison to the secular courts of the day. SlothfulCobra posted:I read that the Spanish even developed a kind of modern racism during the inquisition. Most of the Muslims in Spain were North African in origin, so dark skin became linked with Islamist leanings. Absolutely. Limpieza de sangre or “cleanliness of blood” in the 1400s. The Spanish Inquisition came a little later (started in 1480), but the concept was firmly in place around the same time. sullat posted:Being able to bribe your way out of false/racially motivated accusations of heresy seems about the most fair you can hope for, I guess. Lot of talk about the Spanish inquisition, but as I recall, the inquisition was originally founded to root out a much more sinister menace to Catholicism; the Cathars. Does anyone know how the inquisition went about doing that? The usual torture->confess-> execute route? Or did they, too, let suspected Cathars bribe their way free? Calling witnesses was the most popular method. If you gathered the people, asked anyone if they wanted to make a confession, and that received leniency. This was also the opportunity for anyone else to make accusations. However, this suggests a relatively public proceeding, but other aspects of the trial assume that the accused does not know the identity of the accusers. If the accused told the Inquisitors who his enemies were, and the accuser was one of their enemies, then the trial would be dismissed. The identity was also kept secret to prevent retaliation by the accused. Inquisitorial records seemed to be quite detailed about witnesses, suggesting they were fairly important. Torture could be used after 1254, authorised by Ad extirpanda, although Inquisitions had been going on since 1184. So torture was not the standard. There were also restrictions on the torture, such as not being able to maim, technically only one session of torture (although the session caused by ‘suspended’ to start up again) and a confession was only valid if repeated after the one session was finished, and even then only used if otherwise virtually certain of guilt. With that in mind, torture was not that big a risk of false confessions, as they could be easily recanted... instead the risk was that the trial could go on indefinitely, with the accused sometimes held prisoner for the months or years needed for the trials to conclude. The reason for trying to gain confessions if so sure of the heretic’s guilt was to make them repent. Execution was never desirable with the Inquisition, the goal was to impose repentance and return them to the Church. The aim was something more than "Gotcha." How far these rules were followed is a fair question. It could get pretty bad; almost as bad as trials without the Inquisition. Which I think is the point I am going for, not that the Inquisition was a shining beacon or example of justice, but rather that it was a step forward. It was progress.

|

|

|

|

Obdicut posted:Are you guys going to deal with the fact that clergy started the whole "root out the crypto-Jew" thing at any point? Well, you have not really asked a question, and this is an ask thread. Your comment did not look like it needed any response from me. After doing a little reading on the topic, what I found was mob violence against New Christians – the 1449 riot in Toledo, and another in 1467. The Sentencia Estatuto issued by the secular mayor, which was condemned by the Pope. In 1465 rebels against the king published the Sentence of Medina del Campo, including some harsher treatment of crypto-Jews. These were mentioned in Inquisition by Edward Peters. Those events seem to imply the “root out the crypto-Jew” idea was circulating around Spain without the clergy, particularly when the input of the Church was to condemn some of those actions.

|

|

|

|

swaziloo posted:Thank you Railtus and other contributors, reading this thread has righted more than a few wrong conceptions for me. You’re welcome. I am glad you find it helpful. Travel was done to learn a trade, although medieval households did not entirely conform to the nuclear family of the 20th century. They might even include a few servants, including for well-off commoners, or apprentices etc. The point is households are a little bit larger. This might be important when travelling, as people tended to travel in groups. Maybe a group of the household or several people in the village travel together all heading in the same general direction. Pilgrims normally gathered together for travelling so I assume other groups would organise something similar. The relative safety of travel varied quite a bit. In 1300s-1400s Germany there was certainly a demand for learning self-defence, and travel before then (particularly the Interregnum of 1250-1273, the time of the ‘robber barons’). England appeared to have some roads known for being dangerous, and a similar period of dangerous travel during the reign of King Stephen. With outlaws, they were probably near good hunting sites rather than waiting for a traveller to rob. Outlaws also had an incentive to stay away from the road; anyone could kill an outlaw and take their possessions. Overall I think the risk of robbers on the road was mostly overstated, but it is a bit like wandering the city at night today. Hospitality was practised. If wandering you might be able to get someone to offer you a place to stay, even if only a barn. Monasteries were known for good hospitality, which led to problems of getting too many guests. Sometimes this would result in creative interpretation of their rules of hospitality; the monks might treat you like Christ himself… such as waking you in the dead of night for prayer because Christ would not mind. If a nobleman is travelling you could simply follow his entourage and hope it scares off any trouble. Obdicut posted:Unsurprisingly, that level of research isn't sufficient. You don’t have to agree with me. I find it unconvincing because Alonso de Hojeda, Archbishop Pedro & Tomas de Torquemada were doing what you mention in 1477, by which point the rest of Spanish society was already persecuting conversos. Ferrand Martinez died in 1395, within a few years of the 1391 massacre that led to large numbers of conversos. History of a Tragedy: The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain by Joseph Perez & Lysa Hochroth (page 43 for anyone interested) also gives the impression that Martinez was opposed by others in the church.

|

|

|

|

Forgive my delays, Friday was occupied with dissertation, Saturday I was working, then I slept badly and Sunday had me tired. I will not be able to answer all questions yet. Meat Mitts posted:Excellent thread Railtus. I've got a few questions- Medieval people were on average only very slightly smaller than today, maybe 1 or 2 inches shorter on average (although with peasants being a little shorter and nobles being a little taller). It was later on that people got much smaller. One of the best examples of a successful attack on a castle was the Siege of Rochester Castle in 1215, which lasted 7 weeks. Different chroniclers say different things about how effective the catapults and stone-throwing engines were, but the method was eventually to dig underneath the castle and then burn pig’s fat in the tunnel beneath to burn down the wooden supports. It caused a corner of the castle to literally collapse. I should note that most of the prisoners at Rochester were spared once the castle surrendered, including non-nobles. However, before the surrender of the castle, prisoners were deliberately maimed out of spite. Trebuchets were very widely popular, although used in fairly low numbers. At Rochester there were a total of 5 siege engines, although I’m not sure what kind. In the Siege of Acre 1191 there were 2 trebuchets. So they were popular, but you would not see many. The other form of catapult was a mangonel, but medieval mangonels were more trebuchet-like than the earlier versions. This makes it difficult to tell whether a catapult was a trebuchet or mangonel. Generally I think the trebuchets were safer, so I would prefer them. Castles evolved a huge amount. Individual castles even evolved a huge amount. Motte & Bailey (1000 AD): Essentially a ditch or moat with a stockade (sharpened logs) and the earth from the ditch used to create an artificial mound. On top of the mound was a tower, often of wood. http://resources.teachnet.ie/mmorrin/norman/images/motte.JPG These were relatively easy to build. By which I mean William the Conqueror brought three of them across the channel and assembled them once he got to England. Yes, you could prefabricate an early castle. You can probably see where the motte was on this picture. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikiped...r_wideangle.jpg Later on, the tower on top of the mound was made into stone. These get called ‘shell keeps’. These were mostly just plain round stonework. One interpretation of the term ‘shell keep’ is that the outer walls were stone and the inner structure was still wood or timber. Compare those with Krak de Chevaliers from the 1100s. This held a garrison of 2000 men. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Krak_des_Chevaliers_01.jpg/300px-Krak_des_Chevaliers_01.jpg Lots of small features were added to castles throughout the ages. The change from square towers to round towers. Stouter gate-houses. Arrow-slits changed to gun loops. Portcullises or falling gates were added. Machilocations were openings in the floor used to drop things on the enemy below. Sometimes battlements (the bits sticking out the top of the castle wall for cover) included wooden frames over the top. Eventually castles became concentric, which meant an inner castle with a separate outer wall. Essentially castles changed a lot, but only a little at a time. After cannons, castles became shorter (lower walls make more difficult targets) and thicker. They were also shaped to be more difficult targets, for example lots of triangles so you would struggle to get a good shot at a flat surface. Those complex things are called Star Forts or polygonal forts. Wiggy Marie posted:Another question: is there any way to tell how much sense of humor/sarcasm influenced the writings of the time? Basically, is there a method used to try and determine if anything written can't be trusted due to the author's own sense of humor coloring their statements/descriptions? Good question. We do not have a set policy for humour or sarcasm, we just have to guess, although what we normally do is compare it to other sources, look at the context of the source (is it a personal letter? Is it for public consumption? Is it formal?). If we know who it was written to and why, that can make it far easier to determine how seriously or literally to take the document. life is killing me posted:I really love this thread. I love history and study it a lot for fun, but I had a lot of misconceptions sprinkled with some skepticism on depictions and common thoughts of medieval life. That said, I have some questions for you medieval buff goons. On royal hostages, I think so, although I will need to research again once I have more time. It was not common or standard, although Vlad the Impaler was sent to the Ottomans. They educated him while he was their hostage, but he also is rumoured to have learned his brutality from watching Turkish practises, and developed a rather passionate hatred for them. Knights Hospitaller were different from the Knights Templar in that they started out as a hospital rather than knights, it was a hospice in Jerusalem to provide care for pilgrims on the road, but later expanded to include an armed escort for travelling pilgrims. Comparatively, the Templars started off as a very small armed force (nine knights initially), so the plan was probably to be more proactive and aggressive in hunting down banditry in the Holy Land since they initially did not have the manpower. However, the Templars were given enough resources and financial support that they started working on financial systems including cheques and letters of credit to make travelling easier for pilgrims. Essentially, the Hospitallers were healers who later became knights, while the Templars were knights who later became a heavily armed banking service. The Templars were too successful as bankers, and the French king essentially had them rounded up on false charges, tortured and executed in 1307 – because he owed them far too much money. This caused the other orders, the Hospitallers and the Teutonic Knights (Hospitallers for Germans) to have panic attacks and start looking to form their own kingdom outside the domain of a king. The Teutonic Knights invaded Lithuania and kept having fights with Poland, while the Hospitallers became the Knights of Malta. The Military Orders (Teutons, Templars & Hospitallers) did have a reputation for being nigh-invincible, although this was as a group rather than as individuals. The Hospitallers at Malta did hold off huge Ottoman armies, such as the Siege of Rhodes (1480) holding off maybe 20 000 (some sources say up to 70 000) with only 3000 or so men (of which around 500 were knights). Even the times the Ottomans won the Hospitallers made them pay through the nose for that victory. The big thing about the military orders that made them so effective was their discipline. Knights varied in how disciplined they were as units, they could be well-oiled machines or arrogant nobles out for glory. Knightly orders were less concerned with glory, so they would be far more reliable and organised. They were also relatively rich, which could mean excellent equipment. I suspect monastic vows were partly to make their upkeep cheaper. Wives and children were expensive, so a frugally living knight would be a bargain death machine. Body parts of saints was a thing, although it was far more popular to keep a part of the saint in a church than to cart it around. I have not read the Saxon Tales though. Shield walls were virtually ubiquitous from the Romans up until maybe 1200, where it started to decline a bit but just became one item in the toolbox rather than the default formation. Shields were getting smaller around 1250, which made its use as a formation seem less plausible, which implies the tactical change was going on sooner. Freedom depends on your typical commoner means, but most urban centres (towns and cities) had charters in which most people were free. Also, a lot of rural commoners might be free tenants, with no labour obligation etc, although unfree peasants typically received something in return for their labour obligation such as land.

|

|

|

|

ToxicSlurpee posted:How prevalent were things like pavises and tower shields? I remember reading that a pretty popular thing in and around Italy for a while was to take a big chunk of militia, kit them out with big rear end shields and crossbows, and have them hide behind their fancy little portable walls while raining fire all over everything. Pavises seem to have been fairly prevalent in central Europe from the 1300s or so. They were also used in the Hussite Wars, which had a fairly significant amount of troops who were not really trained warriors. So there may have been truth to the idea. However, most often we hear pavises used in the context of Genoese mercenaries and other professional troops rather than levies. Tower shields generally did not feature in medieval times. The closest we got were the kite shield between 900-1200, which would cover from shoulder to shin. During this time period kite shields were the main shield. A trained arbalester (a special type of high-powered crossbow) could shoot twice per minute. Then again, lots of lighter crossbows are much easier to use. You do get militia with crossbows, although they vary a lot in their power. The more powerful crossbows were more demanding (they still relied on muscle power for the huge draw-weights) and tend to be more expensive, so those would be used by more trained guys. Crossbows were more user friendly, and missiles were a much better use of lesser-trained troops. So yes there was some truth to it, but at the same time crossbows were also popular among the highly trained guys as well.

|

|

|

|

First, my apologies about the delays. I am kind of burned out by the amount of research I am doing for my dissertation, so I kind of put other research on hold. I still have dissertation work to be doing, so I will still be delayed a bit. My apologies in advance. Thank you to everyone who kept the thread going. I will start with a question on relics that is overdue (the post is so far back in the thread I cannot add it to the quote list). Obdicut Good question. I have never seen any official work addressing that subject, although it seems plausible that it was just never kept track of to a sufficient degree to cause an issue. Once you know Church X has a finger-bone of a saint, you probably do not have much incentive to start tracking down the number of other churches which had other finger bones, you just want to go to that church for pilgrimage. Basically the research needed for a medieval person to notice, cross referencing various relics in what churches, would be very demanding and time consuming. I think honestly few people were willing to make the investment needed to do the research. Also it was not too common to claim to have the whole skull of a saint, if you just have a piece of it that counts and it avoids those problems in the first place. However, it was known that not all relics were genuine. For example, in the Canterbury Tales Chaucer describes the Pardoner as selling fake relics, so the concept was generally recognised. The church also made a point of forbidding the selling of relics on occasion, which is a sign it probably happened. So the short answer is they didn’t deal with it. :P I think the church could have made a wide census tracking down exactly what relics were where and which ones were genuine etc. But it seems no one wanted to do it. Iseeyouseemeseeyou posted:Any recommendations on books about The Knights Hospitaller? I like the Osprey books, even though they are not perfect from an academic standpoint they tend to be very accessible. Osprey Knight Hospitaller 1100-1306 & Knight Hospitaller 1306-1565. The second one covers more about their time in Rhodes & Malta etc. Scionix posted:are you familiar with the medieval, total war games? If so, are they historically sound, generally? Medieval Total War is a very fun game. I enjoy it a lot. What I would say is they did their research and then threw out the bits that got in the way of the game. They do take some liberties but it is one of the better-researched games out there. I admit my standard is influenced by how terrible the research behind most media is. The main flaw with Total War is it is about battles, while historically battles were the least popular way to fight. Also, the tax system is far more money-based than most medieval economies, but that is probably boring from a game perspective – they make no secret what the game priority is. I think I made an earlier post in this thread about two-weapon fighting. Generally two swords is bad, they tend to get in each other’s way as much as anything else, and using two swords means that if you are in a situation that puts a sword at a disadvantage, both your weapons are hindered instead of just one. Sword and dagger was popular, at least in civilian fighting. The shorter dagger did not get in the way as much, it was easier to use, and it was good up-close. This way if your enemy is too close to use your sword against effectively you can still gut him with the dagger. Two daggers are uncommon in the fight-books. Normally they depict just a dagger, with the other hand being used for grappling, but it is far more feasible than two swords. cargo cult posted:This is more ancient history but is there a direct cultural and linguistic link from whatever ancient indo-aryan tribes who created Sanskrit and founded Zoroastrianism/Hinduism to Sarmatians/Scythians and then eventually Sicambri/Frisii/Other germanic tribes? I think Scythians are mentioned as allies of Germanic tribes during the Macromanic wars. This may sound ridiculous but all kinds of Europeans have tried to claim Sarmatian/Scythian descent, from Polish nobles to Ossentians. I think Iranians were even considered "aryan" under Nazi law and of course the whole Hitler co-opting the Swastika thing. Not a clue, really outside my area of knowledge. Sorry. Lord Tywin posted:How long did the Knights in religous orders such as the Templars, Teutonic order and Hospitallers serve? How many were in for life and how many were just around for a couple of years? Military orders could do either. Full brethren were for life, while there were also Confreres or Halbbrudern who served fixed terms. The length of these terms could vary, they also had differences in their livery (the white surcoat of the Templars was permanent members only), and they were allowed to be married (although probably not allowed to marry if single at the time). The military orders wanted knights badly enough that they would accept people who could not commit to the full vows. In short, both.

|

|

|

|

Mitchnasty posted:What sort of advantages/disadvantages would a left-handed swordsman have had? Did they exist? Like a Southpaw boxing it would be unusual for the other fighter to have to deal with, although material directly addressing the subject is limited. Liechtenauer’s teachings mention that if you are left-handed you should strike from your left-side whenever possible so you do not get overwhelmed in the bind (when your swords meet). Jeu de la Hache, a French text on polearms, does have a separate section addressing left or right handers. Fiore mentions some techniques that work against left and right-handers. It seems like awareness of the concept is there, but the sources only do a limited amount of delving into it. On the other hand, most military features were built on the assumption of everyone being right-handed. The shield wall assumes your shield is going to cover the right side of the guy to your left, so throwing in a lefty who holds his shield in his right hand would leave a potential weak spot. In pike formations I have seen it suggested that the front rank charge their pikes at waist-height, the second rank at shoulder-height, and the third rank overhead and thrusting down. This works if everyone is using their pike from the same side. Buried alive posted:I've heard that left-handers were good for fighting up castle towers during a siege. Something about the combination of the spiral stair case and the fact that his weapon is on the left instead of the right is supposed to give an advantage..somehow. I've also heard that Alexander put a left-handed person at the corner of a phalanx. Phalanxes had a tendency to drift right as they moved forward, having a lefty on one side fixed that. I don't know if there's any truth to that, but that's a direction to look in. The idea is that tower staircases went up clockwise; meaning that on the way up the wall was on your right side, giving you less space to swing your sword. While the guy defending the tower had the wall to his left side, giving him more room to use his sword freely. Tower staircases were often narrow enough that both fighters were crowded, but if both were right-handed, the defender would have more room and be in a better position to thrust around the wall than the attacker would be. On the other hand, not all tower staircases went up clockwise. Rodrigo Diaz posted:If you're going to use scientific terms you should aim for some kind of accuracy. Why not simply say 'physics', which is the more accessible term, over biomechanics? The sword and shield being 'natural extensions' of the fighter is mysticism, and the point I was making has nothing to do with feeling your opponent's movement through the sword, but the fact that the Forte is stronger than the Debole, which is just leverage. I suspect that English was not their first language, which might have caused errors in their terminology. Rodrigo Diaz posted:Edit: Hey Railtus did you go to the R. L. Scott conference in Glasgow last year? If not you missed some good presentations from Syndey Anglo, Peter Johnsson and Matthew Strickland, as well as a really bad presentation from John Clements. Dierk Hagedorn also presented but I honestly cannot remember what it was about, just thinking it was decent. I didn't, sadly, but I'll see if there are any videos on it. Thanks for the heads up!

|

|

|

|

WoodrowSkillson posted:How so? Blades would be sharpened as much as the metal would allow. Why would they use duller blades intentionally? One reason given is that extremely sharp edges would be somewhat more brittle, and might make the half-sword grip safer (where you grasp the blade with one hand). There is one attack, called the mordhau or murder-stroke, where you grab the blade and use the handle as a warhammer. A less-sharp sword might be preferable if you are doing that a lot. However, I am not entirely convinced. These claims also tend to be very vague about how sharp the sword should be. Which I think is an important factor for this kind of argument. How sharp is too sharp? How sharp is sharp enough? In my opinion, swords needed to be sharp enough for a few things. Firstly, abschneiden, when you cut by pushing or pulling the edge across the target rather than striking it. This technique is taught in the fechtbucher, implying the swordsmen of the time at least expected the sword to do it. Second, harnischfechten, or armoured combat when you try to stab the gaps in plate armour. Most of those gaps have an arming coat underneath, which is made of sturdy cloth. My arming coat is strong enough to resist most of the knives in our kitchen easily enough (which probably need sharpening). However, to my knowledge sources on armoured combat do not consider the arming coat to be an effective barrier against a sharp sword. Extending that thought a little, harnischfechten is always portrayed as being against plate armour; you never see it used against a cloth gambeson. This is not conclusive proof, I know, but it points in the general direction. Third, fighting medieval underwear, a phrase perfect for taking out of context. Even someone unarmoured is probably wearing a linen undershirt and a wool tunic over the top. Even without armour, wearing multiple layers of cloth was the standard. In my opinion, if your sword is not sharp enough to cut through the regular clothing of the day, you are better off with another weapon. Yet swords were popular even if not necessarily common. Fourthly, and most obvious, it needs to be able to cut people. There were bodies from the Battle of Visby with both legs shorn off by a thin blade in a manner that suggests the bone was cut rather than broken through, and the angle of the cuts suggest that both legs were severed by a single blow. Overall, the evidence suggests that medieval people expected their swords to cut and cut well. Finally, one more thought to throw out, remember that swords varied a lot. An Oakeshott Type XVII could have fairly blunt edges, being made principally for half-swording and armoured combat, whereas a XIII was much more cutting oriented. However, as a generalisation, I would say swords cut through cloth or most leather pretty reliably. I have also heard that 20-30 degrees was a common edge bevel, but I do not have a source to back that up.

|

|

|

|

UberJew posted:I've seen videos of people demonstrating that a sword is sharp by cutting things and then half-swording that same sword barehanded with no damage to their hand. The way it was gripped means it isn't actually dangerous. Indeed, as long as you do not let the edge slide on your hand it is reasonably safe. For a few examples of those videos. First, with John Clements https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rqP1F36EMY Second, a much better example in my opinion https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xfb6g786Y8M I think the idea is that a duller edge is more forgiving of errors in technique when gripping the blade. Not my choice, certainly, but someone might prefer the extra security in case they get something wrong in a high-stress environment such as battle. For me, if you are not going to use the sword for cutting then maybe a sword is not the best choice. With the Type XVII swords specialised for armoured combat, I would find a slightly shorter pollaxe much more effective for the same jobs - it makes a better hammer than a mordhau, it has a spear to stab with, and if you need the fine point control of a longsword's balance then you can stab with the queue-spike on the butt of the staff. That said, the Type XVII was fairly popular in England from 1360-1420, so they maybe the knights who used them knew something I do not.

|

|

|

|

Godholio posted:I'm not seeing any reason why a sword would have to be particularly sharp. You're not really slicing in any way that strength or angle won't make up for keenness. More like clubbing, which even if it doesn't get through the adversary's protective clothing is going to make an impact...with leather or cotton particularly, but even against metal armor (and against that, you're not getting through even with a razor edge). Or stabbing. Stabbing doesn't require an edge, just a point. Then use a club, it would make far more sense. Very often you were cutting in a way that strength could not make up for. Abschneiden (slicing off) where you place the edge against the body of your opponent and push or pull the blade along their body. Cuts from the bind (when your swords have met and crossed) would often lack the momentum to compensate for a poor edge. Pressing of hands was a popular slicing technique. Johannes Liechtenauer taught there were principles of successful swordsmanship. These were the help of God, a healthy body and a good weapon, principles of offensive and defensive and of hard and soft, a list of basic techniques, he repeatedly mentions speed and trickery, of being able to read your opponent, footwork and agility. He never mentions strength, which is the kind of thing he would mention if you needed it to compensate for a dull blade or if you were going to inflict injury by clubbing. Fiore dei Liberi stated he would rather face three fights in armour than one fight without, because with sharp swords a single mistake could be fatal. Again, this is a strong sign that swords were expected to be sharp or at least to get through medieval underwear. When clubbing blows are suggested, they are invariably murder-strokes, holding the blade and using the handle to club with. That this is suggested when you need to do impact damage suggests that clubbing with the blade was regarded as ineffective. Just as a final point to add, Sagas such as Heimskringla of the 13th century explicitly mention a king’s men being unable to kill their foes due to notched and blunted swords. When Skofnung was notched by an edge-on-edge blow they tried to whet the blade to get rid of the notch. Clearly the quality of a sword edge was regarded as important. bewbies posted:Also regarding sword sharpness, how much of a factor was cost? I'm referencing the American Civil War, where nearly all swords made were shipped unsharpened as a cost saving measure, then subsequently (in large part) not sharpened by the soldiers they were issued to 1) because they were not used much and 2) because the regiments didn't want to foot the bill to sharpen them in the field. I'd imagine sharpening all of the edged weapons for a medieval army would be a huge logistical undertaking. Cost has not been mentioned in my experience. However, medieval swords were typically associated with the professional warriors who were typically well-funded. It has never really occurred to me at all that it would be costly, since I assumed a whetstone would be fairly common. Certainly the feudal troops (knights and their household retainers) often had squires to sharpen their swords. It seemed to be something that the troops organised for themselves. Rather than having bulk swords shipped out to be sharpened for an army, you would have units called lances fournies (or sometimes gleves or just lances, depending on area) of 3-8 men, and they would typically include their own servant or squire who took care of those logistical details.

|

|

|

|

Godholio posted:I'm not, I'm basing it on the multitude of times I've cut myself by being stupid. People were debating over the degree of sharpness. I'm saying razor sharp is unnecessary. Even abschneiden doesn't require that kind of edge, which as mentioned, will weaken a blade. I'm not saying you can get away with a flat edge. Razor sharp is not necessary, but the fight-books are pretty clear that clubbing to make an impact through normal clothing rather than cutting was the wrong way to use a sword.

|

|

|

|

Rodrigo Diaz posted:It's worth mentioning that a lot of these techniques were designed for unarmoured fighting. Abschneiden (what I called draw-cutting in earlier posts) is the most obvious example. It is within that context, I think, that Liechtenauer speaks of the nature of strength, as I think strength is an inarguable boon against armour, in wrestling with half or in normal strikes. For the value of strong sword blows against armored opponents, consider the following examples from different chronicles and different eras: Excellent use of sources! With Vie de Louis le Gros it does not clearly say whether he struck armour or not, but those are beautiful contributions. Thank you! Liechtenauer’s comments on abschneiden or draw-cutting are definitely blossfechten (unarmoured combat for the benefit of other readers). When you get to harnischfechten (armoured combat) the game changes considerably. Also, by the time of the Liechtenauer tradition, transitional armour was becoming more common with the mail being reinforced, so bashing with heavy blows would be more difficult than previously. Unfortunately the earliest medieval swordsmanship manual I know of is the I.33, so we have less surviving evidence of how earlier swordsmanship was different. A friend of mine once tried bashing vs halfswording, to get very onesided results - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2bdMfaymGlk Then again, earlier combat with shields might have made the use of wider, powerful blows against armour more feasible since you do not have to sacrifice as much defence for power. On the other hand, if you wanted to batter someone senseless, then a mace would be my first choice. An interesting thing is we do get the occasional literary reference to split helms but I have never seen it duplicated in reconstructive testing (which is probably one of the reasons you mentioned to be wary of reconstructive testing earlier). That said, I was very surprised to see a split helmet mentioned in a 15th century source, normally the split helmets tend to be mentioned earlier. Also, excellent point about how common knives were and the dispersal of population. That evidence is really helpful. I was more or less speculating but those details of everyday life is very good confirmation. By the way, do you know any good sources that describe conrois in more detail? I have occasionally heard them mentioned in passing as small teams of knights when reading up on the Normans, but I have never received much detail on them (most of my research has been later medieval, but it has irked me when I saw a book mention a conroi and then go on to say virtually nothing about them).

|

|

|

|

junidog posted:If I walked up to a dude in plate armor and swung a baseball bat as hard as I could at his chest, what would the result be? Would he fell it enough to throw him off? Would it not budge and I'd eff up my wrists? You might knock him back a step, but otherwise it is unlikely to inflict any meaningful injury. While the weight distribution of a baseball bat is better for impact than a sword, there is also some give to the bat compared to the breastplate. Someone trying the same thing with a blunted sword - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hlIUrd7d1Q Or another try here - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3fPHAAqiLI&t=1s Probably not the perfect simulation for your example, but the general trend is swinging hard blows to the chest does not do any serious harm. On the other hand, they do not seem to be complaining about hurting their wrists either. Overall it just seems like a waste of a powerful blow. A metal-reinforced bat would do better, but on the chest if it would still barely get his attention. The arms and legs have typically thinner armour (less weight makes them easier to move), and while the helmet is usually at least as thick as the breastplate the brain is a little more susceptible to the shockwaves from the blow. There is only so much a helmet can do about a concussion.

|

|

|

|