|

On the topic of economic growth, can anybody here think of a major country in the last few decades who has developed without relying on either massive government spending, an asset bubble, or exports to a country with at least one of the former two traits. If we imagine a world where China and the US aren't juicing their economies and buying up so much of what the rest of the world sells then what might the world economy look like right now?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ May 15, 2024 17:19 |

|

This thread kind of dropped of my radar so I didn't realize anybody had responded to my posts. Apologies this is coming in late.asdf32 posted:China has sustained growth through periods of US and western recession. And at this stage the first world is diminishing in terms of its share of world consumption. The upshot here is China, like other successful industrializing nations, relied heavily on the United States (and to a lesser degree, the West in general) as a consumer of last resort. China used export oriented growth to develop rapidly, and the United States made this possible by running a gigantic trade deficit. This has continued throughout boom and bust, so bringing up US recessions is irrelevant when the US hasn't had a trade surplus since the 1970s. Without the United States acting as the buyer-of-last resort I'm not sure how successful various export oriented economies would have been. In a sense the US economy has been stimulating the rest of the global economy with its large trade deficit which is not necessarily the most balanced or desirable path for global growth. quote:So I don't think bubbles or "juicing" have played a necesary role in 3rd world export growth. Well then answer my original question: "If we imagine a world where China and the US aren't juicing their economies and buying up so much of what the rest of the world sells then what might the world economy look like right now?" quote:I also don't see why you'd associate bubbles with [long term] growth. They're inneficient and potentially destructive. Around the middle of the 1970s economic growth in the developed areas of the world slowed dramatically, and the postwar Bretton Woods system broke down. One of the responses that the share of GDP going toward financial activities began to increase significantly. Since this process of 'financialization' began some forty years ago the economy has behaved differently than it did in the past, with growth tending to produce unstable bubbles that inflate and inflate until they collapse and trigger a major crisis. As a result it's very hard to identify countries that with high growth rates that haven't experienced serious problems with bubbles. This seems to have been the case in America, Japan, the 'Asian Tigers', Southern Europe, Canada and, of course, China. Other countries that have done a bit better like Germany or Australia (which I understand may also have a pretty big housing bubble) have in large part succeeded because their economies are oriented around exporting to the bubble economies, in particular the US and China. So this comes back to my original question. Remove the US and China - both of which operate under their own rules and behave in very particular ways compared to the rest of the globe - and what would the global economy look like? How much of the current economic order is based on the very particular behaviour of these two countries, and how sustainable is this arrangement? How stable and desirable is it? asdf32 posted:Sorry I didn't help you more with this: That's a perfect example of how and why Chinese growth doesn't depend on U.S. bubbles If you actually want to have a discussion I'm afraid you're going to have to unpack statements and actually explain why you think they support the case your making.

|

|

|

|

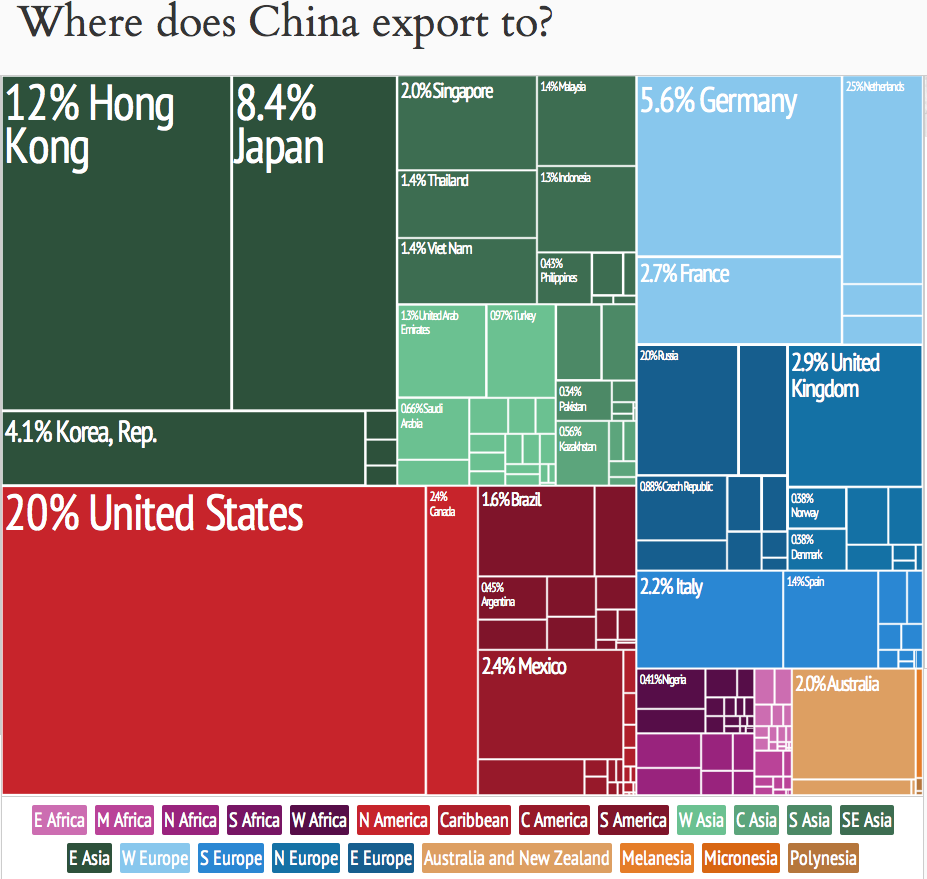

asdf32 posted:I don't know why you think U.S. aggregate trade surplus is relevant to China which cares about what the U.S. is buying from them. I want to point out a few things. First, the U.S. isn't as large a percentage of Chinese trade as you may thin. Looking at the chart below you see large squares for other net exporters like Japan and Germany. On the whole, China exports more to the E.U. than to the U.S. and the E.U. is itself a net exporter. The fact that one dollar of exports out of every five is going to the United States is a massive figure. Obviously China has other important trade partners but the numbers you just provided seem to illustrate how crucial the Chinese-US trade relationship is for Chinese growth and development. quote:Not true given that the U.S. is only 20% of China's exports and I don't know what you're trying to capture with "buyer of last resort". The U.S. isn't deliberately doing any favors by buying Chinese stuff. My comment has less to do with the sustainability of America's trade deficit and more to do with China's reliance on exports. I think the long term consensus is that a balanced Chinese economy would have a much larger domestic market for its own goods but making that transition is a very tricky one. quote:I don't think juicing is a thing and I don't think there is anything that's going to bring an end to high levels of Chinese trade. The US economy is so unbalanced right now and Congress is so dysfunctional that the only way to restore economic growth has been printing huge sums of money to buy up financial assets. The economy is so moribund that this hasn't lead to widespread inflation but it's pushing the price of stuff like housing well above where it otherwise would be and generally making it very hard to know how various assets will be valued once quantitative easing tapers off. I'm obviously not some kind of free market purist who thinks there's some 'true' price for assets that quantitative easing is distorting but what this amounts to is the US Fed taking aggressive and unorthodox measures to prop up an otherwise very weak economy. So I suspect what we'll discover once quantitative easing tapers off is that many US assets are currently priced at levels that will no longer make sense in the absence of quantitative easing. Indeed we may discover that once again the US economy has gone into bubble territory (does anyone think all those tech companies that never turn a profit are being valued accurately right now?). In China we have even less sense of what happens behind closed doors but certainly there are all kinds of implicit guarantees, backdoor deals and outright corruption underlying Chinese growth. China has shitloads of domestic debt piling up and it's not clear how much of that debt was extended for financial reasons vs. how much of it was essentially a political transfer of wealth. Then on top of that we have the government's absolutely enormous post-2008 stimulus plan which involved really massive spending on investments to maintain demand for Chinese products after the western economies slowed down. What this amounts to is that the world's two largest economies, who are themselves locked symbiotically together, are both relying very heavily on unorthodox and largely opaque policies to stimulate growth. And in addition to this both economies are riven with cronyism and corruption, making them even less accountable and even harder to accurately monitor or asses. I don't think anyone fully knows how badly distorted the value of Chinese assets is but there's a growing consensus that a lot of Chinese debt is none-performing and that a lot of Chinese assets are over valued. Likewise it's very hard to say just how stable the US economy would be in the absence of quantitative easing but it may well be that the economy would collapse back into recession without it. quote:What I take you to be implying is that Chinese growth isn't sustainable or isn't more widely applicable. I disagree. At the most basic level trade driven growth is about comparative advantage. It's about trading low skill labor for volumes of higher tech capital. It's not about finance or best explained in terms of finance. As long wage differentials exist there is motivation for rich countries to outsource labor in a way that induces trade. This is fundamentally sustainable and works under a wide range of specific conditions in terms of who the buyers and sellers are, what the specific surpluses are etc. I'm not saying there's something in particular that is wrong with export-oriented industrialization strategies - I think that under the right conditions such a strategy can obviously be successful in building a developed economy. Rather my comment is on the unbalanced and precarious nature of global growth in general. quote:It's not internally consistent to correctly categorize bubbles as destructive yet credit them with growth. Bubbles are market failures. They represent misallocations of capital which only look beneficial while they're happening and then are clearly destructive when they pop. They don't benefit anyone in the long run. (As a side comment I think it's naive to claim no one benefits from bubbles because that's demonstrably false, there are people who came out of the 2008 housing bubble much richer or with much greater market shares than before). I don't think it's internally inconsistent to suggest that capitalism produces dramatic but crisis-prone growth. If you don't want to take Karl Marx's word for it go read Hyman Minsky. This goes back to my previous comment about the move toward financialization since the 1970s. As the financial industry has replaced manufacturing as the central motor of the economy and as debt has started to replace wages as the main driver of consumer demand we've seemingly entered a situation where no economy can grow for a sustained period of time without inflating huge asset or commodity bubbles. This was perhaps less true during the Bretton Woods era when strict capital controls and strong regulatory national governments behaved very differently but in the post-70s world I can't think of any examples of countries that grew at a large and sustained rate without falling prey to very serious bubbles. Can you? quote:I don't know what your question is intending to mean. The U.S. is world's largest source of research and development (notably technology and drugs) and China is the world's largest manufacturer. That's what they mean to the world economy and these are desirable things. The U.S. is slowly receding in terms of its share of the world economy and China is growing. There is nothing fundamentally unsustainable about either thing. (Well actually they are utterly environmentally unsustainable and the relationship is creating a toxic political backlash but that's really neither here nor there in this discussion.) In terms of what we're talking about : I can only say that you seem to have a vastly more positive assesment of how stable the world economy is right now. I look at China and America and see two economies being propped up by extremely nervous governments. In both China and America I think there's a lot of fear that without substantial government stimulation their economies would collapse. And taking a step back, I see a world economy that is so unbalanced that it's virtually impossible to create sustained growth at the national level without relying on the irrational exuberance of investors, which leads to a sort of Casino capitalism effect where huge reserves of global capital slosh around the world economy, pumping up various economies and then crashing them again. So the Greeks get a good decade and then they're hit with a Great Depression level economic catastrophe: Japan grows at a steady clip for decades and is seen as the next world power only to crash headlong into two decades and counting of economic stagnation, the US is heralded as the powerhouse economy of the 1990s and yet, by the mid 2000s, is caught in the midst of the worst economic crisis it has faced in more than half a century, threatening to bring down much of the global economy with it. I'd love to be proven wrong if you have counter examples - that was my original question, after all. EDIT - Had to fix some dyslexic typos. Helsing fucked around with this message at 21:38 on Oct 10, 2015 |

|

|

|

e_angst posted:That's terrible political strategy. Raising minimum wage to a level that will be a drag on employment makes the next attempt to raise it that much harder (hell, if there were actual studies/evidence showing that the last minimum wage hike hurt employment that could kill another attempt to hike it for a whole generation). Instead, you raise it to the level that won't be a drag on employment, while also pegging it to inflation so you never have to go through this fight again. The trouble here is that in the long run there's a basic conflict in the economy between how surplus production is allocated. If you want to reverse the general trend of the last few decades, in which a greater share of GDP goes to capital and a smaller share goes to labour, then you can't rely on a simple technical fix like a minimum wage pegged to inflation. Ultimately the shift from wages to profits is a byproduct of the greater power of capital and the reduced political power of labour. If you don't have some form of institutional representation for labour (traditionally this was Big Labour and their political allies, especially within the Democratic Party) then there's always going to be this inescapable tidal pull toward reducing compensation in real terms. The economy is a pereptual series of conflicts between interest groups and if one interest group (capital, or creditors, or whatever) becomes vastly stronger than another (labour, or debtors, or whatever) then you can expect that the stronger side will find ways to increase their wealth in real terms, and the weaker side will see their wealth reduced. You might be able to counter this trend temporarily under the right circumstances but in the longer run I don't think this is avoidable. Basically minimum wage laws can't replace the existence of an actual labour movement or a labour back political party. There's no technical fix for what is fundamentally a conflict of interests.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:You're surprisingly negative about American economy given how it compares to other rich nations right now, notably Europe. I'll be honest, I find this to be a discouraging way for you to start your post because it makes me feel like you completely ignored what I was saying. I think the entire world economy is performing poorly right now. quote:Well the fact that inflation isn't high sort of contrasts with the idea that that there is mounting asset bubble. And setting aside our recent housing based financial crash it's otherwise a bit difficult to link housing with other narratives like quantitative easing because of the amount of special attention housing gets (fannie, freddie, tax credits etc). I don't know what you consider "high inflation" to be but by most standards inflation was not particularly high in the years building up to the 2008 crash (it spiked to about 4% in 2007 but even that is only about a percentage point above the long term US average) nor was it alarmingly high in Japan prior to their crash. Besides, why is it hard to imagine we could simultaneously have near deflation in some parts of the economy (a reflection of low demand and an extremely weak labour movement that cannot press for wage increases) while blowing bubbles in others (thanks to an excess of capital chasing high return investments and very generous government policies toward financial markets)? quote:Well crappy tech startups are a bubble in my opinion but hopefully a minor one and I've always found housing price growth rates to be alarming but with otherwise low inflation it's hard to think we have a terribly large mounting bubble. Quantitative easing is pretty logical policy during times of slack demand and low inflation and it's reasonably straightforward to see that as inflation ticks up it's time to end it. I don't necessarily see cause for concern (qualified by large amounts of uncertainty that acompany any economic prediction). I don't really see how the supposedly central purpose of the market, i.e. "price discovery", can reliably occur during a period of quantitative easing. And quantitative easing really only makes sense as a policy insofar as traditional fiscal policy is politically impossible and traditional monetary policy is ineffective because interest rates are already so low. Again, this all just comes back to my central point: highly unorthodox and opaque policies by the world's largest economies are the only thing holding off another economic collapse, and this has been true since 2008. The fact you don't see this as a cause for greater alarm about the stability of the global economic system is curious to me. quote:Well I'll say that I don't feel confident that I understand the inner workers of the Chinese government and it's clear that all of China's growth hangs off their decisions. But in the big picture China isn't greece. Their growth has been the result of them building things and the result of them putting people to work in increasingly skilled and productive ways. That is sustainable growth and I tend to think that even if they have a crash they'll be able to weather it. Japan - a country with a lot more political stability to begin with - also massively ramped up their productive capacity and probably had the most sophisticated and automated factories in the world by the end of the 1980s. This did not save them from two lost decades and counting of economic stagnation. Under a different economic system enhanced productive capacity would indeed mean greater wealth but under capitalism that is absolutely not guaranteed. quote:Well that's not a terribly interesting thought because everything benefits someone even if it's the morgue in a plauge. It's interesting because a bubble is caused by humans whereas a plauge is a natural event. The US bubble, in particular, was triggered by the behaviour of people and firms who knew that their social and political power would insulate them from the potential ramifications of their actions. quote:The inconcistent part would be to imply that the bubble get any credit for the growth. There is a suble difference between that and noting a correlation. The economy doesn't benefit in the long term by employing 100's of skilled workers to develop pets.com before throwing it in the toilet. What I'm saying is that there are no clear examples of fast growing large economies that didn't experience major bubbles and/or rely heavily on exporting to bubble economies. This was my original question and so far I don't feel you've provided any examples. quote:Well as a really long aside my economic thinking originates from summers spent playing starcraft while watching the History Channel play endless loops of WWII documentaries. This has to do with economics because the overarching narrative of WWII was supply. It was the economies of the U.S. and the Soviet Union which won the war. Honestly I find these statements a bit jumbled. I do not see how anything you're saying here relates to my comments about the financialization of major economies post-1970s. You'll have to clarify why you think this addresses anything we're talking about. quote:I can't see big picture economic stuff from quite the same perspective here. I see both the U.S. and China on fundamentally decent footing and I think the US's comparatively good growth since the crisis demonstrates that. And I think if the economy is on decent footing then goods will probably keep finding their way to consumers. Many of the finacial concerns you raise can prevent this, but usually (and hopefully) in the shorter term. My suggestion to you is that what happened to Japan was an early warning of what is happening to most, if not all, advanced economies. In fact the Japanese story of a rapidly inflating property bubble followed by a very anaemic recovery is very reminiscent of what happened to the US and what may be happening to China right now.

|

|

|

|

On the topic of the $15 minimum wage it looks like it's proceeding in Sea Tac following a court challenge.PBS posted:TRANSCRIPT Meanwhile in New York a panel appointed by the governor just recommended the implementation of a $15 minimum wage, phased in faster in New York City but eventually covering the entire state. I will point out again that this is not really a technical policy - or at least not exclusively a technical policy - but rather a question of whether struggling workers can actually enforce their political interests onto a system that mostly excludes them.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ May 15, 2024 17:19 |

|

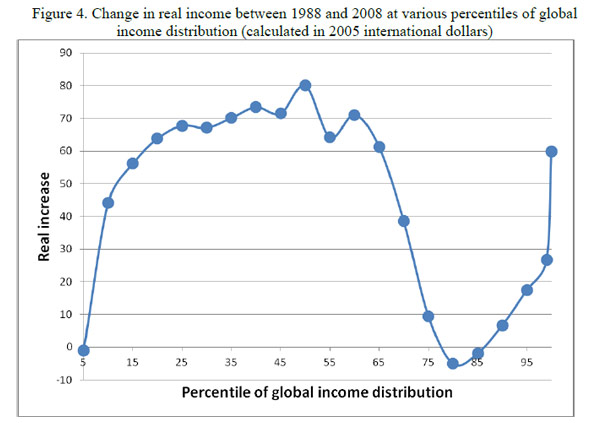

I feel a bit weird necromancing a thread to reply to a post from almost a month ago but I got caught up in election related crap and then got kind of distracted. Also this discussion wasn't exactly leading to an exchange of ideas. That having been said I did want to address a couple things before moving on.asdf32 posted:Umm, why? We're probably coming off the best 2 decades or so in worldwide economic history with high growth and probably no increase in inequality. That means on average everyone has benefitted (and the notable losers are ~80th percentile). Even though I can anticipate how you would wiggle out of this claim it's still a really stupid thing to say. quote:So what do you want? The 1920s was followed by the 1930s. Japan in the 1970s and 1980s was followed by Japan in the 1990s and 2000s. Rapid growth is, if anything, historically correlated with dramatic and painful crashes. quote:Well we can but it's less likely with inflation hovering near zero and less likely to have a large impact if it does pop. Ok then why did a period of relatively low inflation in the 2000s result in an epic asset bubble pop in 2008? By the way, one of the guys widely recognized as having predicted the 2008 crash is not exactly feeling bullish about the US economy right now. quote:I don't really agree. Generally increasing the money supply increases demand for everything which doesn't impact the most important aspect of prices - relative value. The exact values of QE are public and the impact of printing money isn't exactly a mystery and consistent with Keynesian policy. The history of capitalism is also riddled with long and ruinous periods of deflation or economic depression which exactly what I'm warning about. Yeah I guess if you're comfortable with the idea of a repeat of the Long Depression from the 19th century or the Great Depression from the 20th then everything is hunky dory. Your argument about economic fundamentals is also, frankly, dumb. Productive assets are irrelevant under capitalism [i]unless they can produce a profit for their owner.[/url] There are plenty of historical examples of productive assets being allowed to waste away because the demand for their use wasn't sufficient. quote:Well besides noting that Japan is near the top of the GDP per capita list and therefore I'm not terribly concerned about them I'll say that they are a really interesting exception. Clearly there are no fundamental economic problems preventing them from growing so the problem is financial or political. Beyond that I don't know what to say except that yes, it's possible that any country could stop growing like Japan. I just don't see why I should think that will happen. For example China is decades away from that type of GDP per capita. If there is a hard upper limit on GDP growth then that's probably a good thing for long term inequality. quote:If you say so... That's how capitalism works? Just look at Japan (or America after 1929). You can have a skilled labour force and lots of capital and still end up with resources laying idle if there's no way to profitably employ those resources. quote:I'm still not convinced you have a coherent definition for bubble. The countries sitting at the top of the GDP per capita list that have almost all been there for decades aren't bubbles. They have experienced bubbles but their economies aren't explained by bubbles. Instead of just repeating the things you already believe give me some evidence. What would propel growth in the US economy over the last couple decades if you take away the housing bubble? And why hasn't growth returned to its historical average? quote:I already noted how China has grown through U.S. recessions and overall, developing economies were far less affected by the crisis and bounced back to pre-crisis growth quickly. The mechanics of trade and comparative advantage that are the basic drivers of export growth continue to work even when the rich countries stall out (which is basically what's happened in the last 7 years). Comparative advantage is not the basis for trade between advanced economies, Chinese growth estimates are unreliable, and China's growth since the crash has relied in large part upon a massive internal stimulus, as well as selling to countries that also have unstable or crisis prone economies right now. quote:China continued growing through the crisis and so did India: This doesn't address what I'm arguing. quote:The idea that Japan represents the future of the first world is possible. I just see no reason to think it is at this point. But comparing Japan to China makes no sense given the massive wealth disparity between them. China hasn't hit the middle income trap, let alone the upper income trap Japan occupies. Even if the entire first world stagnates it's another leap to decide that 1) that matters much to the rest of the world or 2) is a bad thing in the big picture (they've already been growing slower for decades).

|

|

|