|

Introduction Welcome to the newest paradox Mega-campaign lp thread! Or at least, that is what I will be attempting. For those who don’t know, a paradox mega-campaign is when you start in one early game, usually CK2 and at the end convert to the next title in the timeline, which in this case will be EU4, usually continuing until you hit the Hearts of Iron games. Now, being as I am a mediocre player and Amalfi is a tricky start, I welcome all advice, both in terms of gameplay and when the time comes around, modding. Who will we be playing as? We will be playing as Archon Marinos Polkarios of the Duchy of Amalfi. That’s this guy:  A 57 year old Elusive shadow. Won’t be lasting long, but that’s just the first update. As for the duchy itself, Amalfi is a one province Titular Duchy republic on the south-end of Italy. In the start date, 867, south Italy is divided amongst several one-county and two-county provinces, along with the Byzantine Empire and the Alghabid Sultanate of Africa. It is unusual among republics in that it’s Patricians families are not all the same culture: two are Greek and three are Lombard. What makes this LP different? Well, I am using CK2+, which is a good mod, but that’s been done. What really makes it different though is the nature of the realm: we are a republic, not a feudal realm, which will have a drastic effect on the nature of this LP. Thanks to the magic of the console, it is possible to switch player characters mid-game. The load screen does the same thing too though, technically, but that takes a little longer, so eh. In any case, to make where I am going with this clear: I will always play the leader of the republic of Amalfi and I will spend nothing on campaign funds. I mean, sure, I could always game my way into having my family be the undisputed leader of the republic for all time, but then it literally isn’t a republic. What are your goals then? Well, for one, to keep the Independence of Amalfi at all costs, which will have the incidental impact of negating some of the more common strategies for them (mostly revolving around swearing fealty to the Byzantines). As for more immediate goals: gain enough of south Italy to secure my independence, try to finagle my way into getting us a kingdom and of course, extend our trade empire to every corner of the sea. Of course, I’ll be doing this roleplaying, so it’s not gonna be easy… This might be a very short LP. So, what is Amalfi anyway? It’s a small Merchant Republic in the south of Italy that exists in the earliest bookmarks of CK2. To be frank, Amalfi isn’t what you would call a well-known power, historically speaking. While it is reckoned as one of the first of the great Italian Maritime republics, it is also the most obscure and the weakest, historically speaking, at least of those who even get to the point of being playable. What this means is that there is not a lot known about it: just that it changed hands many, many times over the course of being a republic, and then afterwards. In Ck2 it’s also one of two republics that show up in the earliest start dates, the other one being Venice.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 27, 2024 20:00 |

|

Table of Contents Marinos Polkarios First Steps: Marinos Polkarios 867-867 Sico Mauro The Amalfi Federation: Sico Mauro 867-876 Guilds, Gods and Heart Attacks: Sico Mauro 876-880 Leo Urso 880: First Meeting of the Amalfi Assembly 881: Intermission: The Fourth Council of Constantinople West by North-South: Leo Ursuo 881-884 NewMars fucked around with this message at 18:11 on Aug 28, 2017 |

|

|

|

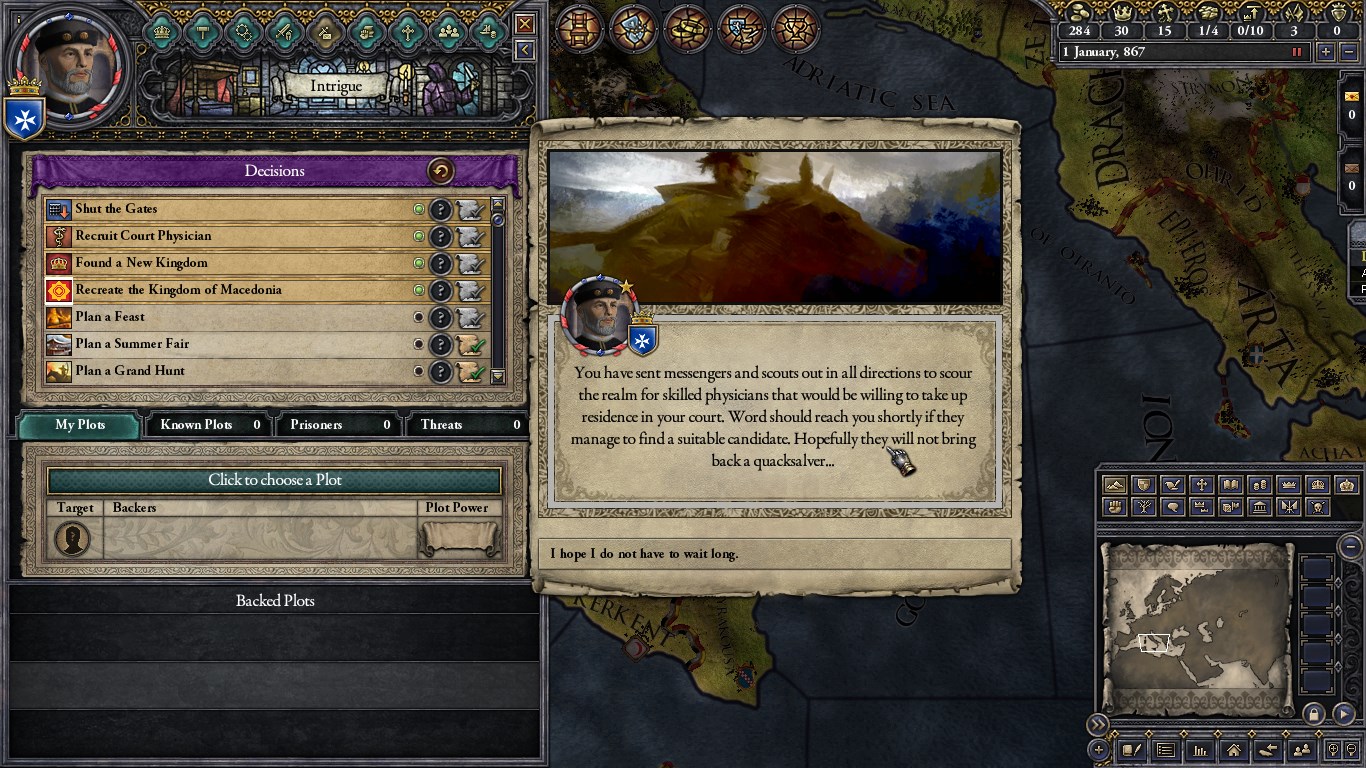

First Steps: Marinos Polkarios 867-867   In 876, the north of Europe was in turmoil. The great heathen army had descended upon the Anglo-Saxon realms of Britannia. But, all this was a footnote to the people of Amalfi, at the other end of their world.  Amalfi was at this time, a small trading hub, barely a village by modern standards. Just barely able to maintain control of the surrounding coastline, to the great empires to its north and east, it was unnoticeable. But in the mind of the elected Archon, Marinos Polkarios, it was a stepping stone to greatness.  Blessed with a cunning mind, though only basic competence in other areas, Marinos was not a man who held great esteem for the church. In his mind, priests were an obstacle to power like any other rival. But he was a patient man, willing to wait to see his will done.  Speaking of obstacles to power, in the republic of Amalfi politics at the time were dominated by five trader families. Of these, three: The Mauro, Musco and Urso were Lombards, with the remaining two: the Polkarios and Konstantinos families, being Greek.  Among his council, the archon was well-liked enough, though he was heard to refer to his Steward, the Patriarch of the Mauro family, as a “Buffon Lombard” in private. This aside, he was also in the unfortunate position of having no one to trust with matters of espionage, a situation he was constantly on the lookout to fix.  As for family matters, he doted on his singular son, Polkarios Polkarios (Names were not his strong suit), who was an unremarkable sort, except for his hideous hunchback, which made him adverse to social situations.  In a standard example of patrician politics, he was married off to Anna Konstantios, a scion of the other greek family leading the republic.  Family matters being settled, Marinos looked to his personal health. At the time his court priest was also his doctor, a situation that the cynical man found unbelievably atrocious, leading him to send out a call for a trained professional.  Like all plutocrats, he believed that the best route to power was money. Granted, an army helps, but you can’t pay one without cash.  And his finances secure, Marinos looked to his first conquest, a target to secure his place in history. The Komes of Neaopolis, a fanatic who was obsessed with collecting gold, was an easy and tempting target.  Being a man possessed of a subtle and insidious nature, Marinos decided that an outright invasion might draw the unwanted attention of surrounding Komes and Doux in a very definitely unwanted way. This led him to seek a pretext, one he found in the mayor of Neapolis; and one whose effects would send a shock throughout history, bending the course of things in ways that could not have possibly been foreseen by Marinos. To this end, he sent letter, the infamous “Trespasses” stated that the Komes had infringed on the traditional rights of the city of Neapolis, which had lead to the city’s mayor reaching out to the Archon, who at that moment was on his way to reassert the independence of the city and restore it’s privileges. Truth be told, we cannot know if the letter was forged or not. The Komes, by contemporary accounts, was not a good or kind man, but there is no evidence to show that any of the offenses detailed in the letter had ever actually occurred. Or, for that matter, that the traditional rights it cited actually existed. Whatever the truth was, it did incite the Komes to behead the mayor and allowed Marinos to invade without undue alarm by his neighbours.  From the outset, things were grim for the Komes, for the army of Amalfi outnumbered them by 500 men and anyone could see that it was a forgone conclusion.  So confident was Marinos that he rode at the forefront of the battle, eager for blood.  Such was the scene when he came upon one Sergios Spartenos, a commander of the Neaopolian army.  Unfortunately, Sergios was a far more skilled and aggressive attacker. Marinos held his shield and stood his ground for hours, not giving an inch, but unable to move forward, until at last, the stubborn old man’s defences caved and a blade drove right into his heart.  Well. That didn’t take long, did it? Any inaccuracies are because that screen is from a test run. NewMars fucked around with this message at 20:12 on Aug 5, 2017 |

|

|

|

Already starting with the parallel universe, eh?

|

|

|

|

ThatBasqueGuy posted:Already starting with the parallel universe, eh? Nah, I just wasn't able to get the death screenshot, while the exact same thing had happened in the test run and I managed to get that.

|

|

|

|

Let's see where this goes

|

|

|

|

More Paradox LPs for the Paradox LP Gods!

|

|

|

|

We are off to a fantastic start.

|

|

|

|

NewMars posted:867-867 Well, well, well! I'm rooting for the Mauros, personally.

|

|

|

|

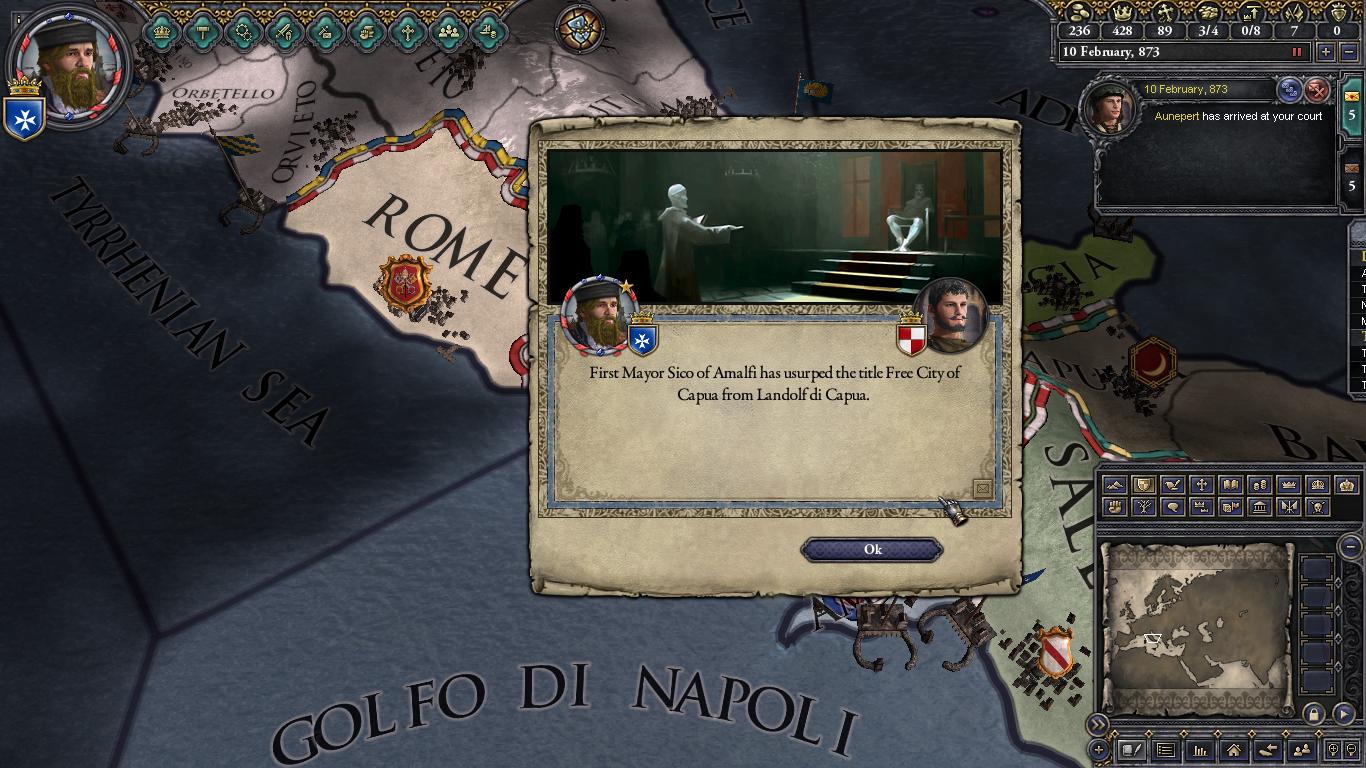

The Federation of Amalfi: Sico Mauro 867-876  As soon as the news arrived back in Amalfi, before the battle was even over, Sico Mauro, a kind, charitable man by all accounts, was sworn in as the new Archon, or “First Mayor” as he preferentially called himself. Strangely, though Marinos had probably fabricated his reasons for invading Neapolis, Sico believed in them wholeheartedly.  In a speech to the 750 reinforcements he brought to the ongoing conflict, shortly before setting off towards the battle, which was still-ongoing, Sico made clear his intentions to protect the rights of not just Neapolis, but all the cities of “Magna Grecia” against empires and tyrants.  Riding to battle, he left his son, Stefanus Mauro at home. Blessed in all aspects save warfare, the relationship between the two was not the most loving, but far from the least, too.  With enough troops to outnumber the enemy 2-1, the reinforcements were more a formality than anything else, as was the ensuring siege of Neapolis.  Upon taking control of the city proper and following the surrender of the Komes, Sico set forth his terms: the city of Neapolis was heretofore under the protection of the Republic of Amalfi. While the city proper would be the exclusive property of its free citizens and the archon of Amalfi, everything beyond its walls and the palace of the Komes within would be retained by the Komes.  Despite the importance of this new acquisition to the republic, most of its contemporaries were focusing on larger matters: such as the migration of the Magyar peoples into modern Hungary.  At the time, Sico could not have cared less. Upon the aqusiition of the new city, he had set into a fervour and discovered that despite his vast theoretical knowledge and skill in smaller-scale endeavours, conquest was an exacting and painful process, even for the victor.  Shaken by the sudden increase in his financial need, he did anything he could to maintain solvency. Coins from his reign are notable for the sheer amount of debasement present in them: while it is uncommon for “gold” coins to actually contain any real amount of it, coins from his reign do not even contain bronze, instead being badly-painted copper.  But Sico was not just a plutocrat, no. His contemporaries, even when they hated him, always noted how he was a man not given to boastfulness or cruelty and indeed, his actions in war and administration showed an uncommon kindness for the period.  But the stress of rulership never left him, causing him what would be recognizable in later periods as stress-induced ulcers.  Thankfully for him, his court doctor, the very same Bishop his predecessor tried to replace, was a noted early proponent of stress-management techniques. His seminal work, the Codex of the Spirit was a volume of such exercises, derived from the monastic practices of orthodox monks. But, while the attentions of his doctor could save him from the physical effects of his stressful life…   ...Nothing could save him from the emotional wear of it.   Even his attempts to pursue fulfilling pastimes, such as hunting, ran into problems spawned by his relentless pursuit of money to keep the state solvent.  Not that it wasn’t causing enough problems without that, mind you.  As if purely to make matters worse for the man, thanks to the satirical poetry characteristic of southern Lombardy, the public’s perception of him had become that of a fat vulture: swooping in when the war was already won to waddle off with more gold than he could carry.  His reaction to these rumours was characteristic: avoiding his court by going on prolonged hunting trips in the hills, at least when he wasn’t locked in his room, working.  Yet somehow, during all this time, he managed to father a second son, Ibor Mauro.  Not that paternal success helped with the population’s hatred of his supposed greed and cowardice.  He was growing old, too, perhaps too much to fight anymore.   At least it could be worse, at least he was not in Bulgaria. The Bogomils had managed to even gain control of the king there, converting the kingdom almost fully to their odd mix of Manichean Christianity.   Sadly, his third son only added to his woes: cleph was not a strong and healthy boy by any means and the medieval rate of infant mortality made his outlook grim. Thankfully though, in the competent hands of the bishop-doctor, the boy’s life was safe.  To celebrate this occasion, he had coins minted bearing the image of his beloved newborn. Coins, mind you, that turned from gold to green in heavy rain.  Not that he cared anymore about what color people thought money should be, for he had unravelled the enigma of gold: if people will use it as money, it is.  This revelation even helped to break his deep depression, though it did nothing to help with the ongoing stress of managing the republic.  Speaking of said management, it was at this time that he truly came into his own as a ruler, from working on his reputation among his most trusted advisors-  -To investing in the infrastructure of the republic, including restoring the old imperial mail system on a local basis.  Though his family suffered for this.  Especially his unfortunate son, Ibor, who was bitten by a rabid rat that had managed to sneak it’s way into his chambers one day. Incurable by ancient medicine, he expired within the year.  Still, despite his work and family tragedies, Sico still found time to relax.  Perhaps it was an attempt to distract himself from troubles at home, or maybe he believed the time had come for his grand project to begin, but whatever the reason was, a week after the diagnosis, he set his eyes on the republic’s weak neighbour, Count Landolf.  Just as his predecessor did, he sent a letter to the count, giving him a formal declaration of war. But while his predecessor Marinos had almost certainly engineered his reason for attack, Sico’s letter was much more plain in intent: he had come to forcibly seize the assets of Count Landolf and raise Capua to the status of free city within the Republic. Even though the republic outnumbered him terribly, Landolf rode to battle at the forefront.  But not before burning the Mauro trade post within the city.  The count was not the only one at the forefront, for Sico too lead his army at the front, possibly in an attempt to put accusations of cowardice behind him.     But he was not the coward upon that field. The full incident is recorded in the Book of Hours, the chronicle of the young republic. There it reads that upon sighting the count, the First Mayor let force a scream, filled with the rage and heartbreak of his hard life, causing the cowardly Count to turn and flee in terror, bounding over the hills, pursued by Sico, who cut through a score of men in his path, until the Count’s horse threw him and the Mayor ran him down, taking him prisoner.  This was followed by a victory parade through the city, to the Count’s residence, where he was forced to sign a treaty abdicating all his assets to the care of the republic, as well as granting the city status as a free settlement, under the protection of the Amalfi republic. The stance of the people themselves on this development lies unrecorded by history.  Once back from his triumph, Sico continued his attempts to endear himself to his advisors.   However, he also laid down the foundations of his grand project. Records from his personal correspondence indicate that he saw the ascendancy of the counts and dukes throughout the peninsula as a direct threat to the tiny republic and the townships of Italy. More close to home, he was paranoid about the possibility of military postings, which were hereditary in the republic, leading to a potential coup. In order to deal with this, he endeavoured to bind them in a web of legalism removing their forces from their direct control, an attempt he announced during the triumph in Amalfi.  At first it seemed negotiations with the council on the matter had broken down beyond repair.   But then, in a surprising move, the Doctor-Bishop demanded that they begin again and with his aid, SIco was eventually able to bring the council around on his reforms.  It was said in the Book of Hours that he walked from the meeting with his head held high, albeit limping from old war wounds. At least they made sure no one dared call him a coward ever after.  Sico’s odd republicanism had effects beyond his borders too. Upland of Capua, the free town of Gaeta declared itself a republic in the style of Amalfi, claiming rights and privileges for its citizenry and independence from outside rule. What Sico thought of the situation is sadly not known, though correspondence of his seems surprisingly dismissive.  At the time, he was altogether more interested in his southern neighbour, the Duke of Salerno, who had long claimed the lands around Amalfi as part of his legal patrimony, even if he had been unable to enforce this claim.  At the end of that year, Sico forcefully rebuffed his claims in his call to war. Instead, he claimed that the lands of Salerno were in fact, rightfully that of the City of Amalfi’s, as it’s peoples were in fact, citizens of the satellite communities of the city, a claim that was not so much false as about to be made true by force.    Calling up house troops and the levies of the cities left them 500 troops outnumbering the forces of the Duke, but the war was not without difficulties, though they were logistical in nature: the dockworkers of the city refused to carry the extra workload of supplying the navy and smuggling skyrocketed to an all-time high as the conditions of the war strained the fragile economic network of the republic.  As punishing as these problems were at the time, in the end, the republic became stronger for it, as it granted it’s harbourmasters much-needed experience in coping with the conditions of war.  While managing the campaign, Sico was blessed with a fourth son, who he named after himself.  As for said campaign, it was long, protracted and with an end that could be seen in the stars. At the finish, Amalfi was victorious, and the duke forced to accede that the towns and villages of Salerno were in fact, citizens of Amalfi.   Surprising all at the time, Sico actually moved to make this true: drafting into the charter the new class of “Outer Citizens” who were allowed to vote in the election of First mayor as well as run for and hold office in the republic, without living in the town proper awarding this designation to the newly-won population.  No sooner was the ink dry upon the new charter than Sico was off to his next conquest. The target was one Emir Massinisa, a radical who had turned to a fringe of the Sufi tradition to either: gain higher knowledge of the divine (as revisionist supporters claim) or excuse his decadence and debauchery (as contemporaries thought).  Due to his radicalism and the fact that most of his subjects were Greek Christians, the Emir was severely limited in the manpower he could raise, which made the events of the war itself rather secondary to its diplomatic repercussions.    The first Mayor led the charge in the war, still so terrifying to his enemies that none would dare face him.  But compared to the earthquake in the east, that meant nothing. The Caliphate of Baghdad had all but fallen, restricted to the city proper and little else, but the Caliph still had some power in the spiritual realm, enough so that when the Byzantine empire struck deep within their lands to take a hold of Jerusalem, while the Sicilian and South Italian emirates were under assault from without and within by Christians, he was able to announce that the time had come to renew Jihad, that Islam itself was under siege. Not that it meant much at the time, though it would come into undoubted importance later.  Ironically, Amalfi actually expanded its network eastwards because of this. With the declaration of Renewed Jihad, the armaments market suddenly skyrocketed in value, allowing Amalfi merchants to make a killing selling to both the Greeks of the Empire and the Emirs and Sultans they threatened.  Many of these weapons even ended up in the hands of the Haruiyyah, the sacred brotherhood formed at the announcement of the Caliph.  Not that Sico cared, he was having far more fun hunting for food to feed his army whilst they sieged the shorelines of the Emirate.  The priesthood were unamused by his lackadaisical disregard in who his merchants sold to. He still did not care.  At the end of the war, instead of taking direct protectorship of the liberated territory, instead he insisted that they hold local elections and instituted a policy of assigning the countryside around major cities as satellite communities, giving them the status of Outer Citizenry to their nearest municipality.  This was concurrent with his attempts to restore the old highway system along the coasts.  As well as a third distribution of coinage that contained less gold and silver than their weight in seawater.  876 was to be a fortuitous year for Sico. With the matter of warring settled, he could turn his attention to financial matters: right now he needed money, and lots of it. This is what lead to his decision to conduct a trading expedition into the depths of the Rus.  Still annoyed with the clergy, he did not let them come.  His actions with his host of course, were much more personable. Of his journey to Kiev, much is known, for he wrote a sizable tome, the Rus and Other Peoples, which detailed his observations of the area.  In the end, the two parted amicably and the trade network of Amalfi reached in those days all the way from Sicily to Scandanavia.   But the gold the first shipment brought with it had a dramatic and immediate effect, for at last, Sico had enough material backing for his grand project. Upon the 7th of September, in the year 876, Sico Amalfi unveiled his grand charter: The Articles of Federation. These documents, while conservative and backwards by modern standards, were a radical innovation at the time: they guaranteed the place of Amalfi as “first city” of a mutual federation of the municipalities of Magna Grecia (as the greek speaking populace still commonly referred to it). While the cities of the Salerno coast were subsumed into a republic under Amalfi, those outside this area were to be given the state of Free City, being allowed self-government, suzerainty of surrounding communities and permission to organize into mutual republics with neighbouring cities so long as they contributed to mutual protection of the federation and acceded trade rights to the republic of the First City and its families.  With their signing, the republic of Amalfi was subsumed into the Federation of Amalfi, with Sico Mauro as its first chancellor, his Project at last complete. NewMars fucked around with this message at 14:12 on Aug 6, 2017 |

|

|

|

Wow, that's uncharacteristically quick for a Paradox LP. With how well #1 did I was expecting significantly more failure and flailing about before we actually made our way anywhere.

|

|

|

|

This is interesting and republics are cool.

|

|

|

|

Yessssssss republics are mechanically interesting and the most fun to read about, but I always struggle in getting one off the ground.

|

|

|

|

Hopefully this merchant republic LP doesn't involve getting our capital nuked in EU.

|

|

|

|

theblastizard posted:Hopefully this merchant republic LP doesn't involve getting our capital nuked in EU. That'd be preferable.

|

|

|

|

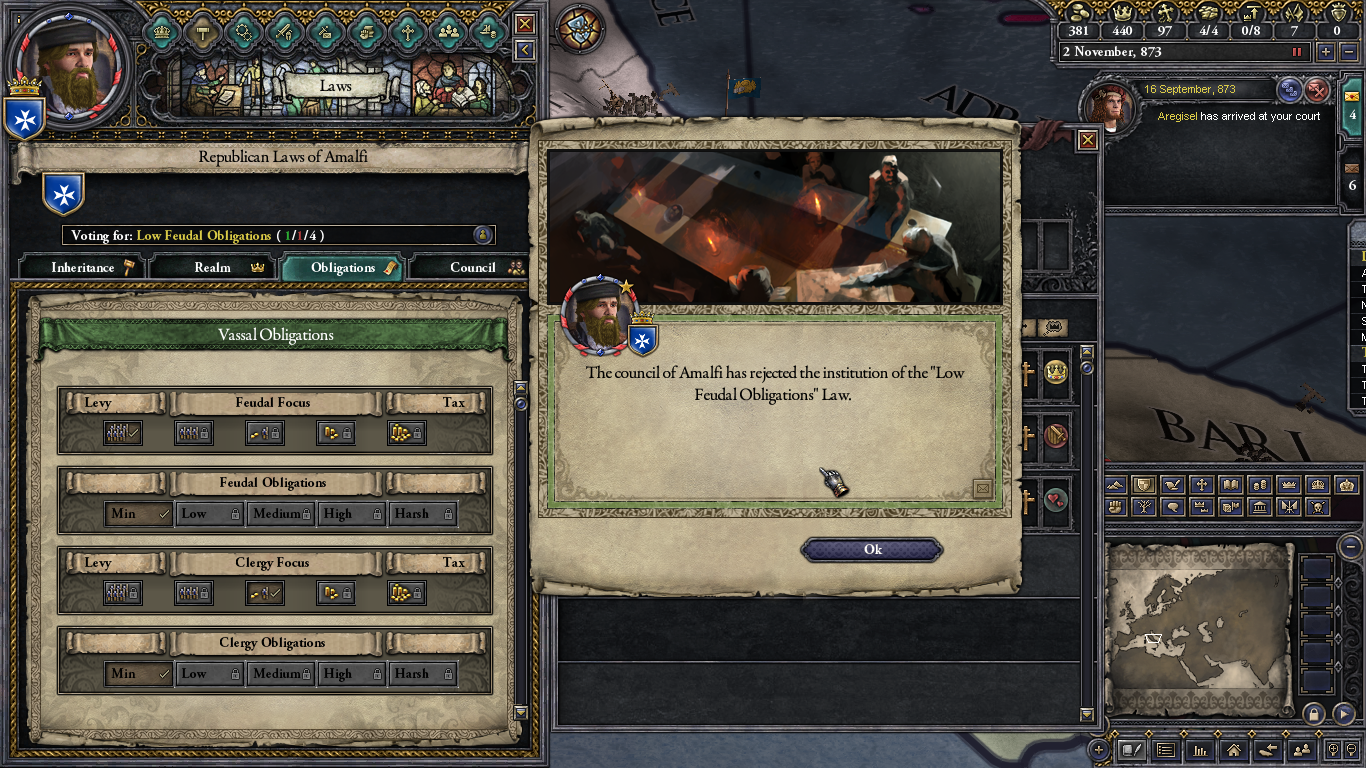

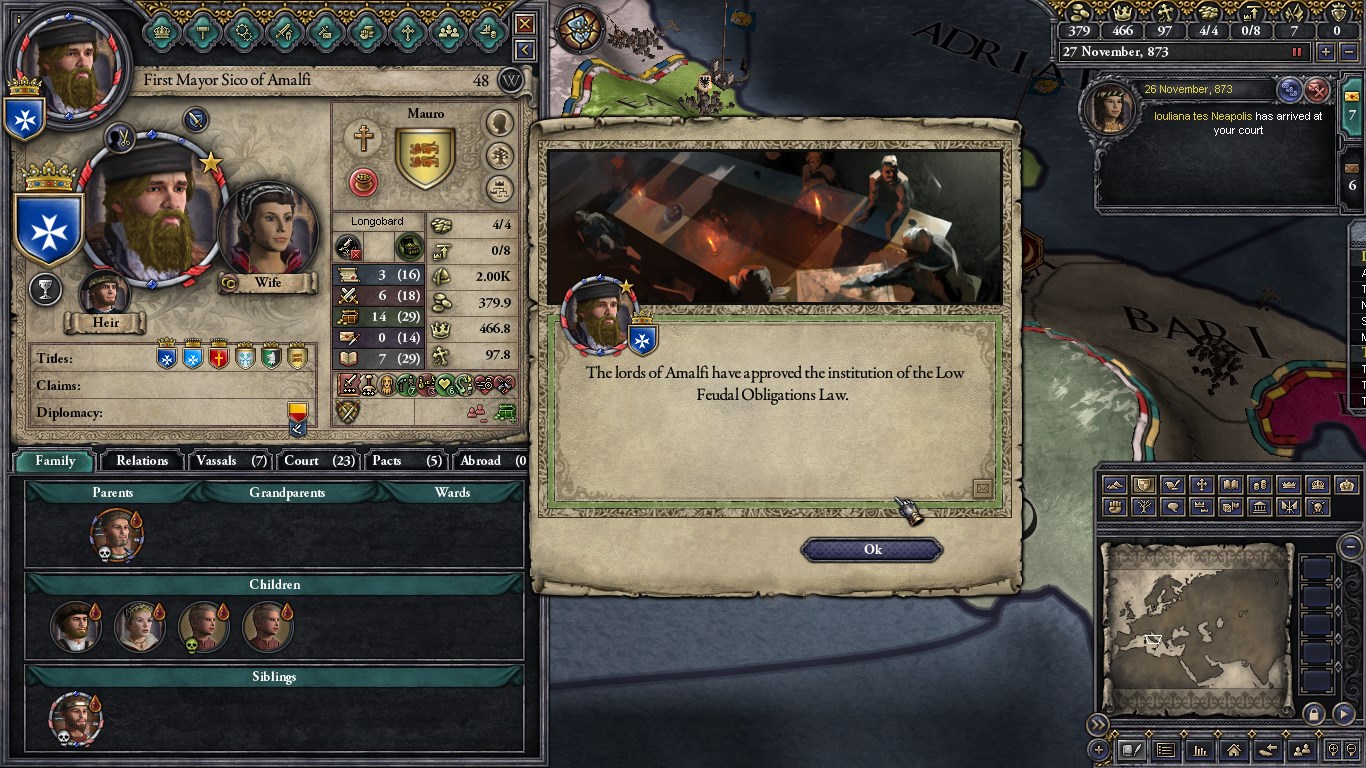

876-880: Sico Mauro: Guilds, Gods and Heart Attacks  From “Medieval Italy: a Revisionist Perspective” by Micheal Keinzatz. With his grand work, the creation of the federation complete, something had changed within Sico Mauro, his ambitions were complete and his gaze turned inwards, to the structure of the federation. At that time, there were three major power blocks within the burgeoning league, described in the travelogue: “The Lombards and Other Peoples of Magna Grecia.” First was the church, which was undergoing minor theological issues foreshadowing the major cracks between east and west developing elsewhere. They had little land and power, though with the Papal state to the north to be compared to, this was really a relative estimation. What they had did allow them to take up a middling place between the community and the nobility. Secondly was the strongest power: the nobles. This was where the major separation between greeks and lombards, culturally in these blocs lay. Lombards tended towards extended clans in both the towns and countryside, drawing power from a fortress or tower, which they lived around, creating the famous “tower societies” in the cities. They tended to have little in the way of titles but far more force to draw upon, compared to the Greeks. Greek nobles, on the other hand, tended to dwell in or around townhouses and administrative structures in the cities. Unlike the clans, they tended to consist of single families, usually with the patriarch claiming a title bestown upon them by the Roman Empire (which at this point still claimed southern Italy in name if not in fact, aside from the very southernmost tips) or the archon or mayor of their community. These titles were usually respected regardless of origin and usually came with privileges such as allowing the holder to draw up a specified number of men from a community as soldiers, or a share of the proceeds in any levied trade duty. Finally, there was the communities. The largest of the three classes but also the weakest by far, what the common people of Amalfi had going for them was mostly the ability to vote in the leaders of their villages and towns. While the leader of Amalfi and its constituent republics did need to be elected as Archon or Mayor of their “First Town,” these elections were shockingly corrupt by modern standards. Mass-bribery was not only allowed, but expected and voter intimidation, usually led by Lombard nobles with access to tiny urban armies, could escalate into almost miniature war. Less overt manipulation also existed, of course, such as Greek nobles calling up as many men as allowed for their army the day before elections. Of course, people in Amalfi were very much aware of this, leading to the observation in the Book of Days that “The only profession in Amalfi more dangerous than soldier is voter.”   Perhaps no one was more aware of it than Sico himself, at least if his actions past that point are looked at with a critical eye. Almost immediately after the federation’s founding, he began to strengthen the communities against the nobles through patronage of craftsmen fraternities, the forerunner to the guilds of the later medieval era.  Not that the nobles weren’t aware of this. As a result, many of the nascent fraternities patronized by Sico failed to gain purchase due to harassment by noble clans, when they didn’t fail of their own accord.  Those that did, however, paid massive dividends in both creating a voting bloc capable of going toe to toe with the urban nobles and providing a source of wealth for the burgeoning federation, though as history would show, they would later foster their own problems.  Curiously, he never sought out the church as a counterweight to the nobility. In both personal correspondence and official matters, he seemed to refuse to acknowledge them as much as possible, given the mores of the time. In fact, the dozens of unopened letters he received from prominent churchmen begging him for money are one of the best-preserved historical artefacts from this period.   Foremost among his family matters, his beloved 4th son, Cleph Mauro, blind at birth was the light of his life. Incredibly, Sico taught to fight despite his handicap, something he did for no other within his family. On an odd historical note, notes on his training later formed the basis for a minor school of blind-fighting established in Amalfi.  As for political matters, the unthinkable had happened. A trade dispute in one of the republic’s northern ports had led to a riot, which was, granted, a fairly common event. However, this time a minor venetian noble had been caught in the crossfire and a trading vessel of the Doge had been burnt in the harbor. The reaction of the Venetians was immediate: an ultimatum was sent to Sico: hand over the offending city immediately or else they would take it by force. At this point in time, Venice was the dominant republic of Italy, it’s trade networks the most extensive and the forces it could draw upon to wage war the largest. Though Amalfi outdid it in terms of land, much of its territory was newly acquired, useless in terms of providing protection.  This would be the first real test of the Amalfi Federation as a concept. The entirety of its existence had been based on a rhetoric of self-defense against the great empires to the north and east. If they didn’t stop Venetian ambitions, the very foundations of the league would have shattered. Luckily, the other families foremost in Amalfi politics understood this too and raised their house troops, pooling them in defence of the league (and their own holdings, of course).  Combined, they added almost two thousand troops to the armies of Amalfi, leading to a bloody, one-sided battle. There, upon the field at Cannae just as in the days of Rome, battle was joined again.   It was swift, brutal and short. The Amalfian army closed upon the Venetians and the Doge, there at the front, was captured as he attempted to run upon seeing the full size of the enemy while his flanks broke. Held at swordpoint, he was forced by Sico to pay forth his personal wealth and the entirety of the Venetian treasury as reparations to the federation, as well as to personally affirm that neither he nor his armies would set foot upon Amalfian soil so long as Sico lived.  The war completed, Sico was petitioned by one of the major blocs who aided in the war: The republics of the coast of Apulia, led by Lord Mayor Orson of Bari. As Sico had set down in the founding charter of the federation, they petitioned for the right to organize themselves into a republic under the federation, a privilege that Sico granted to them with neither wrangling nor double-dealing. That Lord Mayor Orson was a close friend of the Chancellor, mentioned often and glowingly in his personal correspondence, surely had little to do with this.  In celebration of his triumpth and the founding of the new Republic, Sico called for a celebrational minting, a coin that would have a representation of the second battle of Cannae on one side and his face upon the other. Samples recovered from this minting indicate that not only was there no precious metal within them, but that Sico had managed to cut back on the quality and quantity of the tin and brass used to debase them. This was, incidentally, around about the time the Amalfi coin came to be informally known as the “Stone” or “Roccia,” as it was said to contain more sheet rock than gold.  With the war with venice over and done with and the federation’s armies still in strength, Sico decided to take down one of the few remaining thorns in his side: the Komes of Neaopolis. With this his goal, he delivered a simple ultimatum to the Komes: pledge allegiance to the federation, or be divested of his remaining lands and titles. Perhaps there was a time when he would have accepted this offer. But that was before Sico had stolen his city and captured him. His reply was terse but illuminating, the very first occurrence of the words verbatim “Go to Hell,” in the historical record.  The war was short, with little worth mentioning. Sico simply surrounded his palace within the city and waited him out while the rest of his troops occupied the countryside. In the end, the Komes was dragged before him in chains, thrown into the dungeon and forgotten about. Such was how Neapolis came fully under the dominion of the Federation of Amalfi.  With this done, Sico retired to take care of domestic matters. Minor religious quibbles had risen up across the republic about the controversial sainting of King Almos of Hungary, who had converted the nomads settled in the Pannonian basin. The focal point of the controversy is the nature of sainthood: did the pope have the right to declare a man a saint without conference with the rest of the Pentarchs? (Quadrarchs, at this point in time). Such was merely another event in the long and angry divisions between the eastern and western churches.  Surely more interesting to Sico’s mind was the state of his family mansion, which remains a site for tourists today. Funded by venetian coinage and misappropriated gold and silver, no less than three new wings would be commissioned by him, turning a humble villa into a true mansion. He would not live to see his new estate completed, a fact he was cognizant of, if the reports of his physician are anything to go by.  This surely lead to his final attempt at election reform, aimed at curbing the shocking violence of provincial elections through the creation of a federal advisory body for the Chancellor. His hopes, as recorded in its founding speech, were that a proportional appointment of Nobles, Clergymen and the heads of the Fraternities would give them an alternate avenue for pursuing power that would result in a de-escalation in political violence. This body, the “Assembly” also sometimes informally referred to as a senate, was filled by elected positions. Instead, each member would serve at the appointment of the Chancellor. Though it had only advisory powers, it represented direct access to the Chancellor, an otherwise near-impossible perk.  Unfortunately, this would be his last major act as Chancellor. Two months later, in the December of 880, as he ascended the stairs to his bedroom, his heart gave out, leaving him dead on the steps and the republic in the hands of one Leo Urso...

|

|

|

|

The Chancellor is dead, long live the Chancellor! The Lion Bear!

|

|

|

|

Luhood posted:The Chancellor is dead, long live the Chancellor! The Lion Bear! Yes, the Lion Bear! And I'm sure he'll live up to...  ....Uh. Hrmm. Uh oh. This could be bad.

|

|

|

|

0 Stewardship on a patrician. That's certainly something alright. Also can I request that you not timg every screenshot? I like not having to click on things as I read.

|

|

|

|

Grizzwold posted:0 Stewardship on a patrician. That's certainly something alright. Don't worry, this will be the last time you have to do that. I was too lazy to properly crop, but I've learned my lesson now.

|

|

|

|

Grizzwold posted:0 Stewardship on a patrician. That's certainly something alright. Everything is going to be fine, I'm sure he will grow into the responsibilities of being Chancellor.

|

|

|

|

Just need a push to get us into the next page.

|

|

|

|

Again?

|

|

|

|

880: First Meeting of the Amalfi Assembly  : Welcome, one and all to the first official meeting of the Amalfi Federal Assembly! : Welcome, one and all to the first official meeting of the Amalfi Federal Assembly!Now, I would like to make this very clear. This is an advisory body. You don’t make laws, you certainly don’t make decisions and you do not. Order. Me. Around. Is that clear? Good. Maybe if you give out some half-decent advice I might give you something real to do. Now, let’s get a look at you.  : Alright, first of all: you there, over in the back, with the pointy hats. You all should wear this: : Alright, first of all: you there, over in the back, with the pointy hats. You all should wear this: Now, I’ve heard there are some disagreements among you, something something the pope, ect. Well, it’s all just a minor issue I’m sure, nothing to be worried about. What you should worry about is converting the heathens, protecting the faith, strengthening the church, all that Christly stuff.  : That done? Yes? Well, it’s time for some more important people: over in front, nobles of fine Lombardic Lineage. This is our sign: : That done? Yes? Well, it’s time for some more important people: over in front, nobles of fine Lombardic Lineage. This is our sign: Straight, simple, to the point. Just like us. What do we like? Money! Well, everyone likes that. But what we want also is protection, strong, with all the privileges that should be ours. And the right to live in the proper, Lombardic fashion. Not to mention loyal soldiers and strong lands. We are nobility, you know what we want! Though some of you might advocate joining with our brothers under Carolingan Dominion, which is something I just cannot understand.  : Oh, I shouldn’t neglect our greek brethren beside you, too, I suppose. You’ll be wearing... this: : Oh, I shouldn’t neglect our greek brethren beside you, too, I suppose. You’ll be wearing... this: …I don’t know what that is. But I’m sure it’s appropriate! Not that I’m sure how it relates to what you like, which is, as I understand, bureaucracy, letting people like me appoint things, that patriarch up in Constantinople sometimes, the Roman Emperor, living like those crazy gr- romans over in the east, possibly living under them? I don’t know.  : Oh and uh, last and to be frank, least, you of those “artisan’s fraternities” my predecessor put so much money in. Here, take this: : Oh and uh, last and to be frank, least, you of those “artisan’s fraternities” my predecessor put so much money in. Here, take this: . . Like it? Good. Now what you like is.. oh, I don’t know. People things. Mob stuff I guess. Not getting beaten up at elections. Making money. But ah, that’s a bit redundant. Everyone likes money here! I guess you want rights about how you can make money? Frankly I don’t know what you people want.  : So! Now that’s all settled, it’s time to take a look at the wider world. : So! Now that’s all settled, it’s time to take a look at the wider world.  : Now this here is not quite that. It’s us and the neighbours. I see many vulnerable little spots, right for the plucking. Sardinia is divided, plus there’s that little bitty remnant of that Emir that got crushed southwards. Benevento up there is… tricky though. Our equal. : Now this here is not quite that. It’s us and the neighbours. I see many vulnerable little spots, right for the plucking. Sardinia is divided, plus there’s that little bitty remnant of that Emir that got crushed southwards. Benevento up there is… tricky though. Our equal.  : Westwards of us though is Iberia, which is currently engaged in yet another tiresome Umayyad civil war and little else of interest. : Westwards of us though is Iberia, which is currently engaged in yet another tiresome Umayyad civil war and little else of interest.  : Just south of that are the Berbers of North Africa. The Rustamids there aren’t doing so good, but the areas otherwise an impenetrable mess. : Just south of that are the Berbers of North Africa. The Rustamids there aren’t doing so good, but the areas otherwise an impenetrable mess.  : Speaking of impenetrable messes: the British Isles. A frozen pile of Pagans, Half-Christianised madmen, useless counts and petty kings. A waste of some very nice islands if you ask me. : Speaking of impenetrable messes: the British Isles. A frozen pile of Pagans, Half-Christianised madmen, useless counts and petty kings. A waste of some very nice islands if you ask me.  : The Roman empire on the other hand, is doing considerably better. You see that? That’s scary. The complete collapse of the Caliphate on the other hand, is just hilarious. Man-to-man we could take any one of those squabbling little emirates left behind upon those coasts… especially Cyprus, though we’d have to share with the Romans. : The Roman empire on the other hand, is doing considerably better. You see that? That’s scary. The complete collapse of the Caliphate on the other hand, is just hilarious. Man-to-man we could take any one of those squabbling little emirates left behind upon those coasts… especially Cyprus, though we’d have to share with the Romans.  : Last and most certainly least: Europe! Completely useless, completely frozen and whatever parts aren’t being fought over by pagans and puffed-up barbarians are dominated by the so-called “Carolingan Empire” who also dominate much of our surrounding territory. That’s the end of the world as I know it, or at least as I care to describe it, anyway. : Last and most certainly least: Europe! Completely useless, completely frozen and whatever parts aren’t being fought over by pagans and puffed-up barbarians are dominated by the so-called “Carolingan Empire” who also dominate much of our surrounding territory. That’s the end of the world as I know it, or at least as I care to describe it, anyway.  : Okay, I’m thinking that as well as the realms themselves I should probably tell you about our three big neighbours, in case any of you should be so stunningly ignorant. The one up there, Sultan Muhammad the millionth is probably the one to be worried about, being as he can invade us in the name of whoever when he feels like it and has over twice the troops we do. He is a brutish ignorant savage who likes to fight the “infidel” as well. So, yes. : Okay, I’m thinking that as well as the realms themselves I should probably tell you about our three big neighbours, in case any of you should be so stunningly ignorant. The one up there, Sultan Muhammad the millionth is probably the one to be worried about, being as he can invade us in the name of whoever when he feels like it and has over twice the troops we do. He is a brutish ignorant savage who likes to fight the “infidel” as well. So, yes.  : Way more important than that guy according to the pope, is this one: Emperor Louis the Second. Frankly I can’t tell any of those bastard Carolingans apart, so I don’t have anything to say about him, except that he lost Lothringia somehow. : Way more important than that guy according to the pope, is this one: Emperor Louis the Second. Frankly I can’t tell any of those bastard Carolingans apart, so I don’t have anything to say about him, except that he lost Lothringia somehow.  : Last of all there’s this piece of work: Basileus Basilios. Now this guy, he gets it, right? I mean, that you shouldn’t hold back when you really crack down on the bastards. Man after my own heart he is. : Last of all there’s this piece of work: Basileus Basilios. Now this guy, he gets it, right? I mean, that you shouldn’t hold back when you really crack down on the bastards. Man after my own heart he is.  : Okay with them down, there are just two more people worth mentioning. First is this one, Adelfer Mauro. He seems upset about something, I don’t know. The problem is that he is technically the elected ruler of the republic of Amalfi, but not the Federation. How does that work? Beats me, maybe old Sico should have figured that out. But no matter. What does matter is: how do I deal with him? I don’t care about killing him, I don’t care about giving him.. whatever. I just want him to shut up. How do I do that? : Okay with them down, there are just two more people worth mentioning. First is this one, Adelfer Mauro. He seems upset about something, I don’t know. The problem is that he is technically the elected ruler of the republic of Amalfi, but not the Federation. How does that work? Beats me, maybe old Sico should have figured that out. But no matter. What does matter is: how do I deal with him? I don’t care about killing him, I don’t care about giving him.. whatever. I just want him to shut up. How do I do that?  : Oh, and while you’re thinking that over, take a look at this guy. Ruler of Egypt, but with an army a quarter of ours. I just want to say that Alexandria is a very, very fine city and one I have always wished to own… : Oh, and while you’re thinking that over, take a look at this guy. Ruler of Egypt, but with an army a quarter of ours. I just want to say that Alexandria is a very, very fine city and one I have always wished to own…One final word: our reach is only bound by our ships. Any city we may take so long as we can reach it (that is to say, the seize city CB has unlimited range, so we can take any coastal city). So, now that you’re more or less informed, what do you recommend? NewMars fucked around with this message at 13:58 on Aug 25, 2017 |

|

|

|

To be frank, what Amalfi needs at this time is not more war. What Amalfi needs is development of its docks and markets to ensure the prosperity of our fine city! Should enemies threaten our people, let us strike back and ensure our safety, but for now, let's make our cities strong. Can we take a look at what's currently built in the city of Amalfi? Also, I've been enjoying this LP. It fits well with themes dear to my heart- and I've had a soft spot for you, NewMars, ever since my Master of Magic LP.

|

|

|

|

I like pigs. Armadillos? Half pig, half wolf? Armawolfpig? Not sure what that is, really. But I like it! Anyway, Sardinia seems like a nice, juicy target right about now.

|

|

|

|

Seize the islands of the Mediterranean; Sicily, Malta, Sardinia, etc. .

|

|

|

|

nweismuller posted:

: The city itself? Well, as you can see it's nothing special, really. The mob seem rather angry these days for some reason though. : The city itself? Well, as you can see it's nothing special, really. The mob seem rather angry these days for some reason though.The city is nothing special in terms of development. As for the province, it's rather mediocre. It is prospering, but it has peasant unrest. Also, a trade route from Sico.

|

|

|

|

Well, my vote is for saving up money to upgrade that guild hall to a toll booth. I think toll booth is the next stage.

|

|

|

|

You know what we need? More us! So let's build up what we've got before seeking out other avenues. Securing a strong alliance with Benevento allows us to protect from the Emirs and Sultans in the south, and with them right next door there won't be any sort of delay before our allies can help us prevent the moors from invading. As for war targets sure, Alexandria looks awefully tasty right now. I'd bet they're just one invading army away from being able to rally every peasant from there to Axum though, raising their numbers rather significantly most likely. Sardinia is a much better target, but what's even better than that should be that tiny speck of a duchy just between us and the Pope! Seizing Capua and securing our domain over this side of Napoli is in my eyes the best choice of action, since that opens up even more taxes and Lombards and other things that we like. Luhood fucked around with this message at 15:13 on Aug 25, 2017 |

|

|

|

Luhood posted:

: That's not Capua, we own Capua. Or rather, Adelfer does. The man's too powerful... Anyway! Not the subject. That's Gaeta, another republic like ours. For some reason we can't just go and take it like.. well, anywhere else. So it's a rather hard to get at target for now. Getting at it is up to my half brother Sergius, our ambassador. (chancellor council position rename for republics) : That's not Capua, we own Capua. Or rather, Adelfer does. The man's too powerful... Anyway! Not the subject. That's Gaeta, another republic like ours. For some reason we can't just go and take it like.. well, anywhere else. So it's a rather hard to get at target for now. Getting at it is up to my half brother Sergius, our ambassador. (chancellor council position rename for republics)Suffice to say, that could take a while...

|

|

|

|

Intermission: 881: The Fourth Council of Constantinople Foundations of the Central Church: The Lesser Schisms, By Raymond Aslen. With the capture of Antioch by the Komes of Seleukia at the end of 880, the foundations were set for the fourth council of Constantinople. Preceding councils had proven to be fruitless in resolving the tensions between the eastern and western branches of the faith. Pope Benedictus the fourth, Ecumenical Patriarch Loukas and the Pentarchs of Antioch and Jerusalem came to meet, with the Emperor himself, Basileus Basileios the Zealot, hammer of the Bogomilists, in attendance. No one could have forseen what happened next. The point of contention had been the filioque. It is recorded that for four hours that already extensively debated point of doctrine was talked over, until the emperor, fuming with rage, pulled forth his sword and leveled it at the pope, telling him: "If you will not accede and end this thrice-accursed point, I will remove you and your head and find out there a pope that will!" While he pointed to the hall where the bishops stood. That was the moment it all began to crumble. The pope was a scholar and severely avoidant of conflict. The emperor was many things, aggressive, cruel and cunning among them. The moment he meekly backed down on that point, everything else began to go with it. By the time he walked out, he had given away everything. At the end of that day came the famous "Anakoínosi tis Énosis," or "The Announcement of Union." This document was a transference of any pretension of papal supremacy in all but name to the "Supreme Patriarch" of Constantinople. The bishops were shocked. Several were stated to have fainted dead away. Of course, the council did not end there, but they could not stand against the emperor's force of will. In the end, they walked away having given up everything. Of course, the news of this echoed throughout the western christian world with an incredible variance of results and being one of the pivotal events of the age, many of them were well-recorded. The Abbot of Aachen fell off his horse. The archbishop of Canterbury refused to acknowledge that there had even been a council in Constantinople. Emperor Louis was said to have given an indifferent shrug. Patriarch Paschalis of Amalfi was said to have laughed and sent a warm note to the newly anointed Patriarch Supreme. But there was no great pushback. At least, not at the time. How did the emperor get away with this? The reasons are complex. It can't be discounted that the emperor himself, though widely seen as a tyrant, was also seen as an extraordinary figure, a pillar of Christendom at the time. Combined with the relative ascent of the Eastern Empire's power at the time and the period of insularity the Carolingan empire was going though, there was a prevailing opinion among secular lords that the point was a minor theological matter that wasn't really worth arguing with a strengthened Eastern Empire about. This happens without fail a couple weeks after I resume the save. The Basileus is one crazy guy.

|

|

|

|

We should go and take that tiny little Emirate next to us. Such heathen filth cannot be allowed near to the borders of our glorious Republic? What if they started a holy war or some other such nonsense? I do not want Almafi to be the seat of another Caliphate.

|

|

|

|

I'm definitely a leg man Erwin the German posted:Anyway, Sardinia seems like a nice, juicy target right about now. Seems like something we could actually make a profit out of without overreaching.

|

|

|

|

Pick up the various islands, is what I say. Cyprus (we can share... for now), Sardinia, Ireland, whatever.

|

|

|

|

Erwin the German posted:

A successful adventure is just the sort of thing the everyman loves.

|

|

|

|

Joined for the pointy hats! The beast way to protect the faith is to keep the heathens at arms length. To that end we should drive the Muslims from the Peninsula itself, and then work towards the liberation of Sicily and reclaim it for the holy Church!

|

|

|

|

You know what, I like the number 3 so let's go with this. I also like money, and I like capturing cities to make more money. We should definitely engage in grabbing islands and cities whenever possible. As for that Mauro guy, do you think cold hard cash would make him happy?

|

|

|

|

Let's bring the Greeks back to Alexandria

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 27, 2024 20:00 |

|

Island-hopping! Let's make it Mare Nostrum once again!

|

|

|