|

With all the various doomsday scenarios coming to fruition--climate change, financial collapse, antibiotic resistance and so forth--its easy to forget that nuclear proliferation is additionally a Big loving Problem on top of all that other nonsense, not least of which because as the Cold War has begun to fade from living memory so too has the ability to discuss them frankly as nuclear powers resume pissing on each others' leg Donbass or the Spratlys. Obviously there are still two predominant armed powers, but basically everyone on this list is up to some poo poo globally  Saudi Arabia almost certainly has a place on here, too, and it sure is weird US media blacks that out, probably just a coincidence. As the official forum of politically themed depression there's probably enough expertise to sustain a thread about this, especially if the saber rattling toward Iran or NK starts up again after midterms. There's a whole lot to chew the fat about between all the times we almost blew ourselves the gently caress up over nothing or the mathematics of ICBM interception, but by way of starting stuff off I really like this 2002 essay The Nuclear Game because it approaches both the possibilities and problems of a full on strategic exchange fairly approachably and digestibly until he starts getting very very bizarrely specific about gender roles in the postapocalypse and goldbugging. part 1: nukes are pretty much only useful to prevent getting invaded quote:When a country first acquires nuclear weapons it does so out of a very accurate perception that possession of nukes fundamentally changes it relationships with other powers. What nuclear weapons buy for a New Nuclear Power (NNP) is the fact that once the country in question has nuclear weapons, it cannot be beaten. It can be defeated, that is it can be prevented from achieving certain goals or stopped from following certain courses of action, but it cannot be beaten. It will never have enemy tanks moving down the streets of its capital, it will never have its national treasures looted and its citizens forced into servitude. The enemy will be destroyed by nuclear attack first. A potential enemy knows that so will not push the situation to the point where our NNP is on the verge of being beaten. In effect, the effect of acquiring nuclear weapons is that the owning country has set limits on any conflict in which it is involved. This is such an immensely attractive option that states find it irresistible. part 2: formally, nukes are surprisingly useless in a military sense and everything you guess about nuke targeting is wrong quote:The Nuclear Game (Two) - Targeting Weapons i'm in the process of nuking the character limit so i guess this should be split up.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 29, 2024 12:54 |

|

the gay bomb is real

|

|

|

|

part 3: A-country and B-country, and why it sucks to be in either, the guy gets pretty weird and speculative at the end and frankly thats where he starts to lose me because there's a lot of ways things can break and a lot of ways for it to be put back together, but i generally agree that if the birds fly then you'd better have guns and clean rations in the country or life will Suck Bigly. even moreso, i mean.quote:The Nuclear Game - The Attack And After so yeah that got a little fanfictiony toward the end there, but i think the general points he makes about targeting priorities and what warheads will be aimed where are fairly sound. anyway. nukes. they're around, and most of their practical utility is realized sitting in a lightless room doing nothing and we may or may not finally start a land war in asia over the possibility that more nations will secure themselves against invasion. Cool beans.

|

|

|

|

hey remember when hillary clinton quoted the plot of call of duty: modern warfare when talking about pakistan

|

|

|

|

I genuinely think a lot of the change in tenor toward American military adventurism post-WW2 despite the damage to the country being confined mostly to Pearl Harbor is the bombs' two uses in what for the sake of conversation i'll call "combat" making it unavoidably obvious how pointless the exercise of waging a war to overthrow or prop up whatever regime. Past that point the USA has had a lot of difficulty explicitly stating what the fuckin' objectives were in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, etc, because when you're a nuclear power you're either killing people or you aren't and everything else is just bizarre flailing. quote:It was just another secret of the war. We forget now just how pervasive the atmosphere of classified activity was, but there was hardly anybody, in all of the war's military bureaucracies, who could honestly claim to know everything that was going on. The best information -- whole Mississippis of debriefings and intelligence assessments and field reports and rumors -- went up the line and vanished. And what returned, from some unimaginable bureaucratic firmament, were orders -- taciturn, uncommunicative instructions, raining down ceaselessly, specifying mysterious troop movements, baffling supply requisitions, unexplained production quotas, and senseless rationing goals. Everywhere were odd networks of power and covert channels of communication. No matter how well placed you were, you were still excluded from incessant meetings, streams of memos were routed around your office, old friends grew vague when you asked what department they worked in (a "special" department, they always said -- nobody liked coming out and saying "secret"). Everybody was doing something hush-hush; nobody blinked at the most imponderable mysteries.

|

|

|

|

considering the state of 2018 rural health care, his side observation about "well equipped clinics tucked away in rural places" in 2002 is a real, real rough chuckle.

|

|

|

|

no one would be crazy enough to launch nukes so I don't think it's a problem unless several nuclear powers got into a fight over uh *checks notes* the diminishing water source that feeds most of their agriculture

|

|

|

|

Those are some informative essays but he underestimates the spill over affect that killing hundreds of thousands would have on the neighboring region. Also the author, Stuart Slade, has said some stuff in the past that makes me question his credibility like an insistence that bombers are a superior delivery system to ballistic missiles or the time he got mad at a Norwegian criticizing his bad alt history books and responded by having finland get owned in the following book he published. If you want a good bit of speculative fiction on a future nuclear conflict you should grab the 2020 commission on the nuclear attack against the united states from your library

|

|

|

|

logikv9 posted:the gay bomb is real the f bomb

|

|

|

|

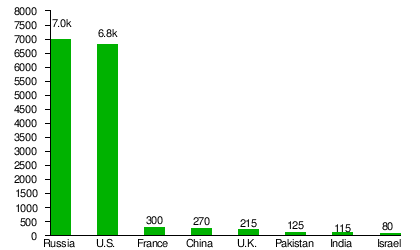

I like to think that most major powers are sane enough to prevent nuclear war, but the fact that Israel is influenced by apocalyptic megalomania and that Pakistan/India are gonna be hit very hard by global ecological degradation is very scary.

|

|

|

|

tldr

|

|

|

|

Metal Cat posted:I like to think that most major powers are sane enough to prevent nuclear war, but the fact that Israel is influenced by apocalyptic megalomania and that Pakistan/India are gonna be hit very hard by global ecological degradation is very scary. pakistan nuking india over that disputed territory seems most likely but donít forget that israel was planning to nuke sinai if they didnít get what they wanted during the 6 days war

|

|

|

|

I watched that tv show Jericho and it was pretty good and if it happens (I hope it does!) Iíll be one of the good guys that doesnít do rapes and only kills people if I have to like if theyíre stealing my food.

|

|

|

|

one of pakistan, india, and china is absolutely going to start a war over their shared water sources in the himalayas once those start to dry up. israel probably will if we ever get a sympathetic government here that tells them to cool it with the genocide

|

|

|

|

A lot of that stuff you quote is pretty garbage.the bitcoin of weed posted:one of pakistan, india, and china is absolutely going to start a war over their shared water sources in the himalayas once those start to dry up. israel probably will if we ever get a sympathetic government here that tells them to cool it with the genocide This is probably going to come true though.

|

|

|

|

the bitcoin of weed posted:one of pakistan, india, and china is absolutely going to start a war over their shared water sources in the himalayas once those start to dry up. israel probably will if we ever get a sympathetic government here that tells them to cool it with the genocide group 1: yeah this is sadly likely although I don't china will start one ever. 2: only if they think they will lose a conventional war and are isolated

|

|

|

|

The Dipshit posted:A lot of that stuff you quote is pretty garbage. Probably. I kinda like some of that analysis, but I suspect the guy who closes his lecture with an extended hypothetical with women being turned into walking Axlotl tanks by the remains of society might be winging a few details. One of the reasons I wanted to post this thread is b/c imo nuke proliferation has become a big ideological blind spot in the US at least, and I know there are a few people floating around the forums with more of a basis to talk about it (you're one of them iirc) and there are surprisingly few nonfiction sources to work from in terms of what a strategic exchange would actually look like.

|

|

|

|

remember when trump wanted to reverse course on how we were drawning down our nuclear arsenal and then put rick perry in charge

|

|

|

|

they named the third xbox the xbone

|

|

|

|

H.P. Hovercraft posted:remember when trump wanted to reverse course on how we were drawning down our nuclear arsenal and then put rick perry in charge is that still on

|

|

|

|

Good soup! posted:they named the third xbox the xbone i doubt this is true

|

|

|

|

Lawman 0 posted:is that still on yeah and he's still Very Retarded here's that terrifying article about the DoE

|

|

|

|

logikv9 posted:the gay bomb is real

|

|

|

|

Willie Tomg posted:Probably. I kinda like some of that analysis, but I suspect the guy who closes his lecture with an extended hypothetical with women being turned into walking Axlotl tanks by the remains of society might be winging a few details. I went to the DOE for work, got my clearance, read some scenarios, and I'll say this: Mad Max ain't too far off once you hit the 2,000 warhead scenarios of a US/Russia/China(kinda, sorta) kind of exchange, even if most of them are assumed to be spent trying to bust other nuke silos in a first strike. A dozen smuggled into the right places (think major ports and naval bases) would push the U.S. into a depression that would be far greater than the Great Depression, and probably kick off one hell of a worldwide depression since the U.S. dollar underpins everything. Oh, and I personally don't like our ability to detect smuggled nukes. I see nuclear terrorism with some of the missing USSR warheads being a likelihood up there with the India, Pakistan, and China. If Israel ever used nukes, they'd be a pariah state, and they know just how dependent they are on the rest of the world. Either we all sing kumbaya, kill capitalism and get along, or we are in for a hell of a century. H.P. Hovercraft posted:remember when trump wanted to reverse course on how we were drawning down our nuclear arsenal and then put rick perry in charge In the weeks before I left, they stopped the plutonium downblending operation to restart warhead pit production.

|

|

|

|

taking the fall of the house of saud and it's last princeling nuking tehran as my dark horse pick.

|

|

|

|

The Dipshit posted:I went to the DOE for work, got my clearance, read some scenarios, and I'll say this: Mad Max ain't too far off once you hit the 2,000 warhead scenarios of a US/Russia/China(kinda, sorta) kind of exchange, even if most of them are assumed to be spent trying to bust other nuke silos in a first strike. A dozen smuggled into the right places (think major ports and naval bases) would push the U.S. into a depression that would be far greater than the Great Depression, and probably kick off one hell of a worldwide depression since the U.S. dollar underpins everything. Oh, and I personally don't like our ability to detect smuggled nukes. thank you nihilanon

|

|

|

|

Cheap satellite launches provided by SpaceX will finally enable SDI to be viable. Once the US completes its SDI network expect Russia and China's spheres of influence shrink drastically.

|

|

|

|

qkkl posted:Cheap satellite launches provided by SpaceX will finally enable SDI to be viable. Once the US completes its SDI network expect Russia and China's spheres of influence shrink drastically. Given how close Georgia and the Ukraine have come to being fully moved out of Russia's influence, how much more shrinking of influence can we expect to see from Russia?

|

|

|

|

I read somewhere that nuclear winter wouldnít actually happen and that the whole theory was soviet propaganda meant to deter an American nuclear strike; thoughts?

|

|

|

|

Dreylad posted:no one would be crazy enough to launch nukes

|

|

|

|

Metal Cat posted:I like to think that most major powers are sane enough to prevent nuclear war, but the fact that Israel is influenced by apocalyptic megalomania and that Pakistan/India are gonna be hit very hard by global ecological degradation is very scary. nuclear war will be started by the united states it doesn't really matter who strikes first, it's US escalation that's gonna make it happen it's probably the US that strikes first though The Dipshit posted:I went to the DOE for work, got my clearance, read some scenarios, and I'll say this: Mad Max ain't too far off once you hit the 2,000 warhead scenarios of a US/Russia/China(kinda, sorta) kind of exchange, even if most of them are assumed to be spent trying to bust other nuke silos in a first strike. A dozen smuggled into the right places (think major ports and naval bases) would push the U.S. into a depression that would be far greater than the Great Depression, and probably kick off one hell of a worldwide depression since the U.S. dollar underpins everything. Oh, and I personally don't like our ability to detect smuggled nukes. once you're launching 2000 warheads and stopped, for some reason, in the middle of all out global thermonuclear war, why wouldn't you spend another 1000 to end technological society on the enemy's continent still got thousands to go

|

|

|

|

twoday posted:I read somewhere that nuclear winter wouldn’t actually happen and that the whole theory was soviet propaganda meant to deter an American nuclear strike; thoughts? No

|

|

|

|

jfood posted:taking the fall of the house of saud and it's last princeling nuking tehran as my dark horse pick.

|

|

|

|

twoday posted:I read somewhere that nuclear winter wouldnít actually happen and that the whole theory was soviet propaganda meant to deter an American nuclear strike; thoughts? yep that kinda thingís been their MO for awhile (even notes that one specifically at the top of the article) basically the attempt was to conflate a nuclear detonation with the effects of a volcanic eruption. this seems plausible if you donít know anything at all about volcanoes, making it an effective piece of propaganda on the american public lol other works of theirs were the american government being responsible for creating aids and the idea that the moon landing was faked

|

|

|

|

Uh, wasn't the biggest public proponent of nuclear winter theory Carl Sagan? ...Was Sagan a Red?

|

|

|

|

No it's real. It's just the overall severity is probably less than what sagan and co were hyping it to be.

|

|

|

|

Mantis42 posted:Uh, wasn't the biggest public proponent of nuclear winter theory Carl Sagan? he agreed with the hypothesis that burning an entire city might kick enough particulates into the air to produce something like it. youíll also note that this is outside of saganís field but you hafta understand that this is still at least an order of magnitude smaller than what a volcano can put out, which does have a global effect tho yeah itís not unreasonable to assume a shorter, smaller, local effect might happen from torching a city, or even all the cities. we see something like that from big wildfires after all, which is why thereís scientific controversy about the idea in the first place still, itís unquestionably soviet propaganda they propagated with the intent to deter

|

|

|

|

a little off topic but can anyone name the song in this video, I really like it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FYRARx3qxI0

|

|

|

|

H.P. Hovercraft posted:still, itís unquestionably soviet propaganda they propagated with the intent to deter So.... itís good? The Wikipedia page is an interesting read: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_winter

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 29, 2024 12:54 |

|

I don't have anything intelligent to say about nukes, but I appreciate the Electric Six reference.

|

|

|

. They have to be evacuated and the people distributed in the B-country to make up for losses there. In the B-country people are ambling around with Geiger counters plotting what's hot and what isn't. At this point life gets grim. We triage the population. One triage is condition. Who cannot be saved and will be left to die, who can only be saved with massive (and probably impractical) effort, those who can be saved with the means available now (the ones who get priority) and who will recover without treatment. On top of this is another triage. The population is prioritized according to need for protection. Pregnant women and children are top, young women of childbearing age second. Young men third, older men fourth, old women bottom. This is ruthless and brutal but its essential for survival. Given a choice between saving a young woman who can bear children and an old woman who cannot, we save the potential mother. We do the same with food. Food and water are checked for radioactivity. The clean food goes to the children and young women, the more contaminated food to the lower priority groups. That old woman? She gets the self-frying steaks.

. They have to be evacuated and the people distributed in the B-country to make up for losses there. In the B-country people are ambling around with Geiger counters plotting what's hot and what isn't. At this point life gets grim. We triage the population. One triage is condition. Who cannot be saved and will be left to die, who can only be saved with massive (and probably impractical) effort, those who can be saved with the means available now (the ones who get priority) and who will recover without treatment. On top of this is another triage. The population is prioritized according to need for protection. Pregnant women and children are top, young women of childbearing age second. Young men third, older men fourth, old women bottom. This is ruthless and brutal but its essential for survival. Given a choice between saving a young woman who can bear children and an old woman who cannot, we save the potential mother. We do the same with food. Food and water are checked for radioactivity. The clean food goes to the children and young women, the more contaminated food to the lower priority groups. That old woman? She gets the self-frying steaks.