|

quote:“That’s very good. Yep. The Upper Missouri Development Corporation, of which I am president and principal shareholder – pardon me, is something amusing you?” Her single eye was like a flint. “Perhaps you think it’s unusual for a woman to be head of a large corporation?” Interesting to see someone no-sell Flashman completely. quote:Well, I’d heard of Yankee enterprise, but this beat the band. Mind you, it wasn’t crazy. A respectable scheme, brought to Bismarck’s attention, might well win a kind word from him, and trust the Americans to know how to turn that sort of thing into hard cash. The beautiful thought was Flashy writing: “My dear Otto, I wonder if you remember the jolly times we had in Schonhausen with Rudi and the rats, when you made me impersonate that poxy prince …” Could I blackmail him, perhaps? Perish the thought. But I could smell profit in her scheme, money and … I was watching her inhale deeply. By Jove, yes, money was the least of it. She stroked her cheek with the hand holding the cigarette and watched me speculatively. Was there a glimmer of more than commercial interest in that fine dark eye? We’d see. Fraser couldn't write any other part of the world like this, you really do get a feel for the endless possibility whitey's mugging for himself on this continent. quote:A business-like bitch if ever there was one; cold as a dead Eskimo, rapping out her terms and looking like the Borgias’ governess. I told her it all sounded perfectly satisfactory. And with that unintented backhand compliment we bring the chapter to a close. Perhaps we'll find out of the town would meet Bismarck's liking... next time! Arbite fucked around with this message at 05:07 on Sep 15, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 7, 2024 04:10 |

|

It's very interesting to look at some of Flashman's period caddishness through the lens of the current day. I mean, he meets a woman who offers him a business opportunity. He assesses, based mostly on some huge assumptions on her appearance (and perhaps a little about her body language and demeanour, but he might well be kidding himself) that she is aflame with suppressed lust for him. So the moment he gets her alone, after trying to flirt a bit and having her be coldly businesslike, he .... just grabs ahold of her and starts kissing her, with a good bit of gropage thrown in? He'd be the villain in almost any other books. While the author is very aware of his villainy, I also suspect that a female author, or one writing today, would at the least have thrown in a few more instances where his 'advances' are greeted as the sexual assaults they really are.

|

|

|

|

quote:The rail trip west was a fine mixture of boredom and high diversion. Custer was in a hysteric turmoil, what between his rage at Grant and his own recklessness in leaving Washington without permission. He was like a small boy smashing his toys in a bawling tantrum while watching with fearful fascination to see what Papa will do. He was all over me again, excusing his ill-temper at the White House as mere frenzy of disappointment; I was the truest of friends, rallying to his side when all others had forsaken him, I was a tower of strength and comfort – what, I would come west with him, even? Oh, this was nobility! Enobarbus couldn’t have done better. Let him wring my hand again. Not having it all there own way, then. quote:“Imagine it!” gloats Custer, bright with scorn. “The arch-hostile in their grasp, and they let him slip! They burn a few lodges, kill an old squaw and a couple of children, capture the Indians’ ponies – which they promptly lose again next day – and Crook counts it a victory. Ye gods, it doth amaze me! Crazy Horse must be helpless with laughter. And Grant thinks he can do without me on the frontier?” He laughed bitterly. “Crook – because he’s scrambled after a few Apache renegades they think he’s an Indian fighter. Well, he knows now what real hostiles are! Perhaps our perspicacious President does, too, and will have to swallow his gall and put me back where I belong.” Yes, peace is a great thing. What were we talking about? quote:“How can I,” bawls Custer, “when he will not see me?”  General Alfred Terry, one of the less celebrated figures in the civil war (post-bellum opposition to the Klan may have something to do with that), consistently aquitted himself rather well. While rarely at the most exciting parts of the conflict he would be well regarded by his peers and found himself staying in the army. Let's continue this awkward position... next time.

|

|

|

|

Genghis Cohen posted:He'd be the villain in almost any other books.

|

|

|

Genghis Cohen posted:It's very interesting to look at some of Flashman's period caddishness through the lens of the current day. I mean, he meets a woman who offers him a business opportunity. He assesses, based mostly on some huge assumptions on her appearance (and perhaps a little about her body language and demeanour, but he might well be kidding himself) that she is aflame with suppressed lust for him. So the moment he gets her alone, after trying to flirt a bit and having her be coldly businesslike, he .... just grabs ahold of her and starts kissing her, with a good bit of gropage thrown in? He’s the villain in these books. Flashman’s a monster, and the author tells us that in so many words several times. He’s just an entertaining monster, so it’s hard to dislike him as much as the character deserves.

|

|

|

|

|

Beefeater1980 posted:He’s the villain in these books. Flashman’s a monster, and the author tells us that in so many words several times. He’s just an entertaining monster, so it’s hard to dislike him as much as the character deserves. He's generally not THE villain of the book, he's usually facing someone worse. Also as the series progresses it's noticeable he goes from villain who steals glory to being heroic, just not willingly.

|

|

|

|

Villain of the books is Elspeth

|

|

|

|

Anne Whateley posted:That's the entire concept of the series, yes Beefeater1980 posted:He’s the villain in these books. Flashman’s a monster, and the author tells us that in so many words several times. He’s just an entertaining monster, so it’s hard to dislike him as much as the character deserves. Perhaps I should have used the term 'antagonist' instead. What I was really getting at in his behaviour in that last excerpt, is that many examples of Flashman's attitude to women aren't the focus of his villainy. They are sort of protrayed more as incorrigible caddishness. I never got the impression, when I was a teenager first reading these books, that there was any real negative view of his constantly objectifying and propositioning women. Maybe that says more about me as a reader at that time. But my reading was always that his lying, betrayal and cruelty were his villainous traits; most of the sex stuff was pitched as him being more honest than his sanctimonious, prim and proper contemporaries. Whereas really it's a lot more of a sinister element of his MO. Norwegian Rudo posted:He's generally not THE villain of the book, he's usually facing someone worse. Also as the series progresses it's noticeable he goes from villain who steals glory to being heroic, just not willingly. I remember describing this cowardly anti-hero to someone and then lending them the book, I believe it was Royal Flash. They came back and said 'what do you mean, he's not a coward?'. Flashman dwells at length about how scared he is at all times, much of his proclaimed motivation is avoiding danger (rarely successfully). But in fact he is strikingly cool headed in action and many times will undertake daring feats to preserve his reputation or avoid a worse danger. There are plenty of episodes where he fights single combats hand to hand. By any sane metric he's a consummate man of action. His cowardice rests on comparison to stuff upper lip Victorian action heroes, who never let a tremor of self-preservation enter their thinking, and on his fairly rational willingness to grovel and blubber if he thinks it's the best way out of something.

|

|

|

|

I mean there's the straight-up rape in book 1, besides all the scenes where it's very questionably consensual (where the woman is his captive, slave, tied up and crying, etc. -- but in the narrative he's sure she's into it). I think that's partly you as a teenager and partly what year it was when you read it.

|

|

|

|

quote:“Do you think he’ll do himself a mischief?” Terry asked me when the suppliant had retired, and I said, on the whole, no, but if he didn’t get his way, Grant would be well advised to stay out of Ford’s Theatre if Custer was in town. The Wellington years had some jolts of reform but this is a bit of an overstatement. quote:“It is difficult not to be moved by his plea,” he mused; he was a proper soft head prefect, this one. “And if this unhappy Belknap business had not arisen, there’d have been no question of Custer’s removal. No – I believe it would lie heavy on my conscience if I didn’t exert myself on his behalf.” What, it wasn't all cheerfully milling about the regimental piano? quote:His senior officers, you see, were fellows of long service and good name who’d held higher ranks in the war than they did now, and it’s no fun for a good man who’s been a colonel, and knows how a colonel should behave, to take snuff from a demoted general. His top major, Reno, who seemed a dapper, quiet, clever sort of chap, concealed any animosity he may have felt, but the dominant spirit in the mess, a big burly bargee with prematurely white hair and a schoolboy’s eyes and grin, called Benteen, seemed ready to lock horns with Custer as soon as look at him. I saw it within a minute of meeting him: he pumped my hand jovially and wanted to talk cricket with me – which I thought deuced strange in an American, but it seemed he’d played as a boy and was a keen hand. Custer listened with a jaundiced air as we discussed those mysteries which are Greek to the uninitiated, and finally observed that it sounded a dull enough pastime, at which Benteen says: “Well, then, colonel, what game shall we talk about? Kiss-in-the-ring or blind man’s buff?” and Custer gave him a glare and took me off to meet Keogh, a jolly black Irishman who had family connections with the British Army – and that didn’t suit Custer either, evidently; I was his lion, I suppose, and to be welcomed as such. Again, there was Moylan, up from the ranks and with sergeant’s mess written all over him, which didn’t stop Custer from mentioning the fact in presenting me. Strong words, strong comparisons, let's see how that happened... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:I have to give Custer the credit for that. In the ten days at the fort he drove them hard, and his officers likewise. If there was a loose shoe or a galled back or a trooper who didn’t know his flank man, it wasn’t the colonel’s fault. He fussed over that regiment like a boy with a new bride; he couldn’t do enough for it, or let it alone. At the same time he was deep in discussion with Terry, who was now on hand; there was great heave and ho everywhere, with inspections and issue of rations and farriers and armourers going demented and messengers flying and the telegraph office open night and day; how the dickens Custer had energy enough for his evening’s jollity I can’t fathom. Okay, maybe a bit of milling about the regimental piano. quote:They didn’t notice I wasn’t singing; I was remembering the remnants of the Light Brigade in that grisly hospital shed by Yalta, croaking out those self-same words in their pathetic pride at having done what no horse-soldiers had ever done before. I thought of the pale fierce faces and the horrid wounds, and the unspeakable hell we’d come through, and the ghastly cost – and I wondered if it was a lucky song to sing, that’s all. Author's Note posted:As a guide to the character and psychological condition of George Armstrong Custer (1839–76), Flashman’s account of him is interesting and, in the light of published information, convincing. Custer was only 37; he had served with distinction in the Civil War, achieved general rank when he was 23, had ten horses shot under him, and was spectacular in an age which did not lack for heroes. After the war his career was less happy; his impulsive temper led to his court martial and suspension in 1867, and although Sheridan had him reinstated, his name was not free from controversy even in victory, as when he defeated Black Kettle’s Cheyenne on the Washita. That he was in an excitable state in the winter of 1875–6, and regarded the coming campaign as a last chance for distinction (and possible political advancement), as Flashman suggests, seems highly probable. The last-minute check received when Grant almost removed him from the expedition can have done nothing for his stability; as one eminent commentator puts it, Custer took the field “smarting”. A friend will help you move, mad friend will help you gather bodies. quote:I felt duty bound to crawl out and see them off in the morning, raw and misty as it was; there’s no sight more inspiring or heartwarming than troops marching out to battle when you ain’t going with them. Custer was prancing about at the head of the 7th as they marched past by column of platoons, with the garrison kids stumping alongside playing soldiers; the troopers dismounted for farewells at the married lines, and then the embracing and boo-hooing was broken by the roar of commands, Libby and her sister, who were riding out the first few miles, took post beside Custer, Terry and his staff assumed expressions of resolution, the word was “Mount!” and “Forward-o!”, and as Reno and Benteen led off in double column we had another burst of Garryowen and Yellow Ribbon. And we'll hear what she rasps out... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:“Good morning. Captain Marsh – Sir Harry Flashman. The captain has been good enough to reserve you a forward cabin, away from the wheel. I hope that’s convenient. Yep. Have you brought your bags? No? Perhaps, captain, they can be brought abroad.” Her cool eye turned back to me. “We have a great deal to discuss before we sail, so the less time we lose the better. I’ve set out my papers in the forward part of the main saloon, captain; I’d be obliged if you’d give orders that we’re not to be disturbed. Oh-kay. This way, Sir Harry, please.” Not one to be off-put by no-selling of their offence, I see. quote:“drat the country, drat Bismarck, and drat you,” says I, taking hold of both of ’em again. What a deuced rare dynamic these two have. quote:It’s one of the secrets of my success with women that however contrary, cool, chilly or downright perverse their airs, I’ll always humour ’em – when it’s worth it. It just maddens them, for one thing. All her tough efficient front didn’t fool me; she was on heat most of the time, I should judge, and while she’d probably had more men than Messalina, she was terrified for fear that her allure would fail her (the eyepatch troubled her, no doubt) – so being female, she had to pretend to be all self-assurance and keep your distance, my lad, till I say jump. Kindly old Dr Flashy knows the symptoms – and the cure. So now I let her rattle on about surveys and options and mortgages and share issues and grants, admiring her profile and waiting for business to close down for the day. And with that brutal climax (and now obligatory reference to I Claudius), we are done with the chapter. Let's see what's down the waterway... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:If you care to examine the log of the Far West you will find an exact account of her voyagings on the Missouri and Yellowstone in the days that followed, but for my purpose the barest facts will do. A glance at the map will show you how it was – she was bringing the forage and gear for Terry’s column which had struck due west from Fort Lincoln across the Dacotah Territory for the mouth of the Powder River; advancing to meet them from the west along the Yellowstone were old Gibbon and his walkaheaps, and they were to join forces and push down into the wild country between the Big Horn and the Powder to find the hostile bands who were in there somewhere – no one had much notion where, for it was territory that only a few bold scouts and trappers had ever penetrated. Crook with a third column was traipsing about somewhere to the south, out of touch with Terry, but as Custer had told me, the hostiles would be effectively hemmed in by the three forces.  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Buford Fort Buford is of course named for the decisive John Buford whose early arrival at Gettysburg set the stage for the perfect clash of temperaments between Meade and Lee that doomed the Army of Northern Virginia. quote:I didn’t much mind; there was even a strange excitement in knowing that this sharp, no-nonsense Yankee businesswoman, all efficiency and assurance, could turn into the most wanton of concubines when the blinds were drawn. I say concubine because she was by no means a lover; she’d talk civilly enough, without much interest, between bouts, but there was none of the intimacy you find in a mistress or even a high-quality whore. How much she enjoyed our couplings was hard to say; how much does a hopeless drunkard enjoy drinking? There was a hungry compulsion that drove her, always in that intense, deliberate way, like an inexorable beautiful machine. Ideal from my point of view, but then I’m a sensual brute, and I dare say if she’d been warm or loving I’d have tired of her sooner; as it was the cold passion with which she gave and took her pleasure demanded nothing but stamina. Hope they remembered to bring the tin of ship biscuits. quote:Terry seemed pleased, if surprised, to see me, and preserved his amiable urbanity when I presented him to Mrs Candy; his staff men eyed her with lascivious respect and me with envy. Marsh had explained our presence, and since Far West could carry far more passengers than there were staff, no objections could be raised. Indeed, Terry made no bones about talking shop with me; we’d got on well at Camp Robinson, and I sensed that he was anxious about his new responsibilities; he’d never campaigned against Indians, and regarding me as an authority on the Sioux, poor soul, and knowing I’d smelled powder on the frontier, he canvassed me in his quiet, cautious way. Not about his duties, you understand, but on whether Spotted Tail might have talked sense to the hostiles during the winter, and the possibility of defections to the agencies. Something else was troubling him, too. Haw-haw. And with that we'll pause and see how this misadventure proceeds... next time.

|

|

|

|

quote:I raised an eyebrow myself when the boy general arrived a few days later, all brave in fringed buckskin and red scarf over his uniform, but with a face like a two-day corpse. He came striding up the gangplank barking orders to his galloper, slapping his gloves impatiently against his legs, brightened momentarily at sight of me, and went straight into a nervous fret because Libby wasn’t aboard. Too right. Older Flash's better nose for trouble is always fun to see. Also in this case toronto isn't referring to the swelling city in Ontario (insert your own Leaf's joke, here) but a native meeting place which would become Miles City, Montana. quote:And now the expedition began to buzz with definite news at last of hostiles far to the south. Reno had been off on a scout, and had found an abandoned camp ground where there had been several hundred tipis, as well as a heavy trail heading west towards the Big Horn Mountains. Custer was in great excitement at this. “The hunt is up!” says he, and was off with the 7th to meet Reno at the Rosebud mouth. Far West was there ahead of him, and I was on the hurricane deck, watching his long blue column jingling down under the trees to bivouac, when I found Mrs Candy at my elbow. Making chat, I asked her what she thought of Custer. It's interesting where she does and doesn't use her catchphrase. quote:That was June 21, and in the evening Terry issued marching orders to his commanders at one of the strangest staff conferences ever I saw. Since it was a vital moment in the Sioux campaign, and every survivor has recorded his recollections of it – not just who said what, but who understood what, or didn’t, or sneezed, or scratched his backside – I must do the same. For I was there, as who the devil wasn’t, except perhaps the ship’s cook and the cat; when Terry summoned the senior men, the journalist fellow stood his ground in the saloon, and Mrs Candy continued to leaf idly through a magazine in her seat at the forrard end, within easy earshot, so I found myself a lounging place against the bulkhead where I could overlook the map on the main table.  Custer's chief scout, Charley 'Cassandra' Reynolds, seemed to be blessed with some foresight but not much rhetoric at the critical hour. Let's see how the plan goes further to pot... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:With that settled, Terry went on to say that he and Gibbon would march up the Big Horn to intercept the Indian force whose trail Reno had seen heading that way; with Crook advancing from the south, the hostiles would be caught front and rear. Meanwhile, Custer and his cavalry would have passed up the Rosebud to cut off the hostiles if they tried to slip out of the trap. Q.E.D. and any questions? I wonder if there's ever been a 1-1 scale reenactment of the Charge of the Light Brigade? Considering the scale and time it aught to be more doable than most famous military actions. quote:In other words, please yourself. That’s what Terry was saying – what he was bound to say – and Custer could throw it in the teeth of any court-martial. Terry was having to trust to Custer’s common sense, and he knew as well as I did what a questionable commodity that might be. But he couldn’t put that into words; a Sam Grant or a Colin Campbell could have said, “See here, Custer, you know what I want – and I know what you want, and how you’ll interpret my orders to suit yourself, and claim afterwards I justified you. Very good, we understand each other – and if you play the fool, by God I’ll break you!” But Terry, the gentle, kindly Terry, couldn’t say that – and really, was there the need? It was just a simple operation against a few hostile bands, after all. George Custer with a machine gun would be like Jimmy McGill with a law degree. quote:There was more talk, but that in essence was the famous Far West conference, and no one was in much doubt what it amounted to. I heard young Bradley’s aside as the senior men departed: “Well, guess who’s going to get there first and win the laurels. Who, the 7th Cavalry? No, you don’t say!” Author's note posted:There is no doubt that Terry wanted a combined operation (this was Marsh’s opinion) but that he could not lay down hard and fast restrictions on Custer. It has to be remembered that a principal concern was to prevent the Sioux escaping, and a strict prohibition on independent action might have resulted in Custer’s standing helplessly watching the hostiles melt away, simply because Gibbon had not appeared. No one envisaged the kind of situation that eventually faced Custer, because no one could guess that the number of hostiles had been badly underestimated. At the same time, there is no doubt that if Terry had been able to foresee the concentration of Sioux that was waiting on the Little Bighorn, he would surely have forbidden Custer to attack it single-handed. Terry’s own report (curiously clumsily phrased for a lawyer) says in part “… that either of them which should be first engaged (Gibbon or Custer) might be a ‘waiting fight’ – give time for the other to come up”. Lieutenant Bradley’s aside is reflected in a note which he wrote after the Far West conference: “It is understood that Custer is at liberty to attack at once if he deems it prudent. We have little hope of being in at the death and Custer will undoubtedly exert himself to get there first and win the laurels for himself and his regiment.” Others thought so, too. Not as hilarious as Fraser's recap of the conference leading to choosing Crimea to hit but captivating in its way. Let's see them all go there own way... next time!

|

|

|

|

Arbite posted:I wonder if there's ever been a 1-1 scale reenactment of the Charge of the Light Brigade? Considering the scale and time it aught to be more doable than most famous military actions. It would be difficult to do so on location given the current political situation! There was a film in 1936, total ahistorical claptrap, Errol Flynn played a British officer and his nemesis was a 'Surat Khan' who he encountered in India and who had massacred British women and children (the cad). So they had this fictional officer set up the Charge with forged orders as a means of killing his dastardly nemesis, who was allied with the Russians and conveniently was visiting their guns at the time. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Charge_of_the_Light_Brigade_(1936_film) I'm not sure if it was an even earlier film, where they did film the charge simply by riding a load of horses down a valley, with trip ropes strung along front. Basically killed most of the horses to get the shots of them collapsing at a gallop.

|

|

|

|

quote:Far West was to move down to the Big Horn mouth now, to ferry Gibbon’s infantry across, and it would be the following night that we moored in a wooded reach, under the loom of a huge bluff that reared up along the southern shore. It was a perfect balmy evening, the boat was quiet now with only Terry’s staff men aboard, and I was smoking a cheroot at the maindeck rail, considering what drill I’d go through with Mrs Candy that night, when here she came from the saloon, very stately in her crimson, with a white silk scarf over her head and shoulders. We talked idly about the possibility that Marsh would be taking Far West back east for fresh supplies shortly, and I found myself regretting that soon our business-honeymoon would be over. Hahahah, yeah. Simultaneously as the opportunity arises. quote:“Well, thank-ee, ma’am. Women have purer motives, I suppose?” Ah, the dangers of getting attached. quote:She was looking askance, and dammit, there were the tears again; she was absolutely weeping – and from under her patch, too. Interesting, that. But God help me if I understand women. “Mind you.” I lied, consoling-like; “I won’t say I haven’t …” But she lifted a hand.

|

|

|

|

O m g

|

|

|

|

Daaaaaang

|

|

|

|

I figured she was working with someone he’d screwed in the previous story/timeline. I didn’t mean literally!

|

|

|

|

quote:For several heart-beats it meant nothing, and then it hit me like a blow. But whereas I’d have acted instantly at a physical assault (probably by flight), the implication of what she said, when I grasped it, so shocked my mind that I stood numb, incapable of movement even when she lifted the scarf abruptly and I saw that she was looking beyond me, and heard the rush of running feet suddenly upon me, and knew that here was terrible, deadly danger. By then it was too late. Of all the dreadful reveals in the series this one got me the most. quote:She was lying, she must be; it could not be true. Cleonie was … where, after twenty-five years? And she had been middling tall, and slender, while this woman was near six feet and statuesque, and had a bold, full face with heavy lips and chin – and Cleonie had been a n******! I stared, refusing to believe, while the bright dark eyes bored into mine, and then I caught beneath the full flesh of middle age a fleeting glimpse of the sweet nun-like face of long ago; saw how the dusky high colour might be no more than cosmetic covering on a skin that time had darkened from the pale cream of the octoroon; how that damnable patch had disguised the shape of her face … but the voice, the manner, the whole being of the woman was so utterly unlike the girl I had … had … And as the memory of what I had done rushed back, she whispered softly: “En passant par la Lorraine, avec mes sabots …”, and the bile of terror came up behind my gag. British indignity at the most perfect of times. quote:“But I had to be sure. Oh, I had to be sure! So …” She slipped the eyepatch on again. “Mrs Candy, you see. And Mr Comber – that was the name was it not? How often I wondered – waited and hated, and wondered – what had become of him. And after twenty-five years I learned that he was Sir Harry Flashman, English gentleman. I didn’t believe it … until I came to New York to see for myself. Then I knew … for you haven’t changed, no, no! Still the same handsome, arrogant, swaggering foulness who used me and lied to me and betrayed me … You haven’t changed. But then, you haven’t been a prisoner of savages, a tortured, degraded slave. Not yet.” A long time for a magnificent revenge. quote:She replaced her scarf round her head, and glanced aside to the distant lights of the Far West – so close, but for me it might as well have been in New Zealand. Couldn’t any of the fools aboard her see, or guess, or intervene to save me from whatever horror was in store? For it was coming now, and I’d have no chance to plead or lie or grovel; she was determined not to give me the chance, the callous, cold-blooded slut. And so goes the most terrifying return in the series. Oh, uh, and how's he gonna get outta this one? Let's see... next time.

|

|

|

|

Out of everything he's done, betraying Cleonie like he did stood out the most to me. It coming back to haunt him is pretty good. Pretty, pretty good.

|

|

|

|

This is what I love about the series: Flashman reliably gets called out on his poo poo. You can point to Fraser’s hatred of the Japanese in his WW2 memoirs or his late-in-life conservatism, and all those are fair. But in the text of the series, he knows what is monstrous and what is not, and makes sure that someone gives Flash hell to his face for most of his really vile actions.

|

|

|

|

|

I have no problem with the twist in theory, but I feel the execution really isn't up to Fraser's usual standards. My theory has always been that he came up with it while writing the second book (Flashman and the Redskins is very much two books released together), and for whatever reason didn't want to change anything significant in the first one so he just added a few lines, leaving the betrayal extremely poorly motivated. He also doesn't actually explain any of her physical changes, just points them out. Maybe she went to Brazil for plastic surgery...

|

|

|

|

This is my favorite reveal.

|

|

|

|

25 years accounts for a lot of physical changes, and maybe Flashman was misremembering her height?

|

|

|

|

Yeah, perception of someone's height is one of the most change-able things about them in my experience. We all know people we think of as taller or shorter than they actually are. I find that twist a very effective one, not only for how she points out how awful the consequences of Flashman's actions were for her, but how casual his betrayal was and how uncommon it is for it to catch up with him. Yes, the two books are paired together, but in Flashman's lifetime (which is partly mapped out by this point in the series) he has travelled all over the world and been in uncounted extreme situations over those intervening 25 years. And he probably hardly gave Cleonie a thought after relieving himself of her like unwanted baggage. He's just so confident that he's untouchable, and to see that punctured so justifiably is awesome.

|

|

|

|

That is stone cold and richly deserved.

|

|

|

|

Genghis Cohen posted:I find that twist a very effective one, not only for how she points out how awful the consequences of Flashman's actions were for her, but how casual his betrayal was and how uncommon it is for it to catch up with him. Yes, the two books are paired together, but in Flashman's lifetime (which is partly mapped out by this point in the series) he has travelled all over the world and been in uncounted extreme situations over those intervening 25 years. And he probably hardly gave Cleonie a thought after relieving himself of her like unwanted baggage. He's just so confident that he's untouchable, and to see that punctured so justifiably is awesome. mllaneza posted:That is stone cold and richly deserved. Oh my yes. I thought Candy might be Cleonie, but I wasn't sure of the whys and wherefores. Now that I am, Flashy you bastard,

|

|

|

|

Finally caught up with the thread after a few weeks of reading just in time for this delicious reveal. I've read the series once upon a time, but clearly not recently enough because I was certainly surprised.

|

|

|

|

Genghis Cohen posted:Yeah, perception of someone's height is one of the most change-able things about them in my experience. We all know people we think of as taller or shorter than they actually are. Sure, but not to this extent. Cleonie is mentioned as being medium height, which in the 1870s is something like 155 cm while Candy is near 6 foot so around 180cm. That is an absolutely massive difference.

|

|

|

|

quote:I still say that if it hadn’t been for that damned gag, I’d have been back on the Far West before midnight, rogering her speechless. And she knew it, too, and must have arranged for my abductors to muzzle me first go off, so that I’d never get a word in edgeways to sweetheart her. You see, however much they loathe you, whatever you’ve done, the old spark never quite dies – why, for all her hate, she’d blubbered at the mere recollection of our youthful passion, and for all she said, our weeks on the boat could only have reminded her of what she’d been missing. No, she knew damned well that if once she listened to my blandishments she’d be rolling over with her paws in the air, so like old Queen Bess with the much-maligned Essex chap, she daren’t take the risk. Pity, but there it was.  Knock out an armada one day, knock over this strapping fellow the next, yes sir, QE I had it made. Wait, what happened to him? Oh. Oh dear. Well, where were we? Oh poo poo. quote:These were random thoughts, you understand, floating up through stupefied terror from time to time. The point was that four damnably hostile Sioux were bearing me into the wilderness with murderous intent, and if there was one thing I’d learned in a lifetime of hellish fixes, it was the need to thrust panic aside and keep cool if there was to be the slimmest chance of winning clear. Cute name, but two stars isn't that many. Well, on both shoulders though... quote:They listened in ominous silence, four grim blanketed figures with the paint smeared and faded on their ugly faces, and not a flicker of expression except pure malice. Then their leader, one Jacket, started to lambast me with his quirt, and the others joined in with sticks and feet, thrashing me until I yelled for mercy, and didn’t get it. When they were tired, and I was black and blue, Jacket stuffed the gag back brutally, kicked me again for luck, and stooped over me, his evil grinning face next to mine. Well, it looks like the comeuppances of Flash's misdeeds are starting to stack, let's see how he suffers further... next time!

|

|

|

|

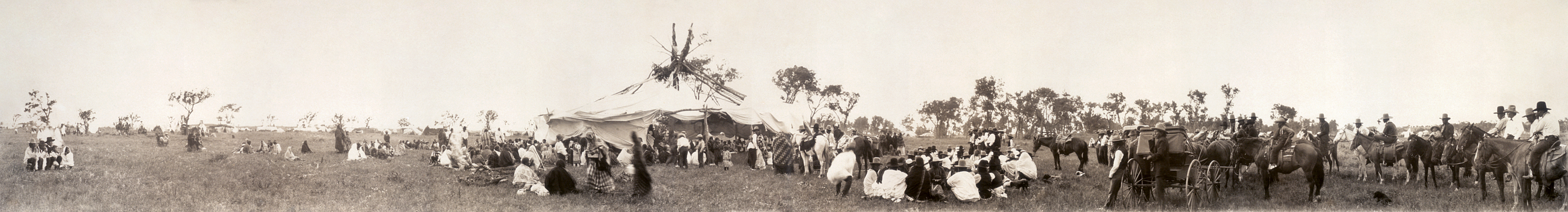

quote:We lay that night in a gully, and every joint in my ageing body was on fire when we rode on next morning. Ahead of us there were bluffs now, and in the gullies we met occasional parties of Indians, hunters and women with burdens, and a few boys running half-naked in the bright sunshine, playing with their bows, their voices piping in the clear air. I caught a glimpse of a river down below us to the left, and presently we reached the top of the bluffs, my guards were whooping and calling to each other in delight, and as my pony jolted to a halt I raised my tired head and saw such a sight as no white man had ever seen in the New World. I was the first, and only a few saw it later, and most of them didn’t see it for long. author's note posted:Estimates of the number of Indians in the Little Bighorn encampment vary, but ten to twelve thousand is a popular figure. It was not by any means the largest assembly of Indians ever known, although other writers than Flashman have made this error; the largest gathering of so-called hostiles it may have been, but there were twice as many Indians present during the Camp Robinson council of the previous year. (See Anson Mills.) The size of the village itself has been variously estimated at from three to five miles long; bearing in mind that the Little Bighorn is an extremely winding river, and that its course varies slightly today from that of 1876, it seems unlikely that the distance from the Hunkpapa camp at the upstream end of the village to the Cheyenne at its other extremity was more than a bare three miles.  This is a photo of a Cheyenne encampment from about 1909. Also it's been a minute since I praised GMF's ability to paint a landscape with such economy. quote:Well, there they were, all nice and quiet in the morning sun, with the smoke haze hanging over the vast expanse of tipis, and the women and kids down at the water’s edge, washing or playing, but I didn’t have long to look at it, for Jacket led us on to a ravine that ran down from the bluffs opposite the centre of the great camp; only later did I learn that it’s called Medicine Tail Coulee, and that the river, which is hardly deep enough to drown in and half a stone’s throw across, was the Little Bighorn. I hadn't heard that trick about knots and gagging before. Hopefully it doesn't come up, but these are terrible times. quote:“Keep him that way till I come again,” says he, and kicked me two or three times before swaggering out with his pals, leaving me in a state of collapse on the scabby buffalo rug against the tipi side. The girl collected her dishes and went out, without telling me to ring if I wanted anything. Well, let's see if a few seconds with a pretty face is enough to save him... next time!

|

|

|

|

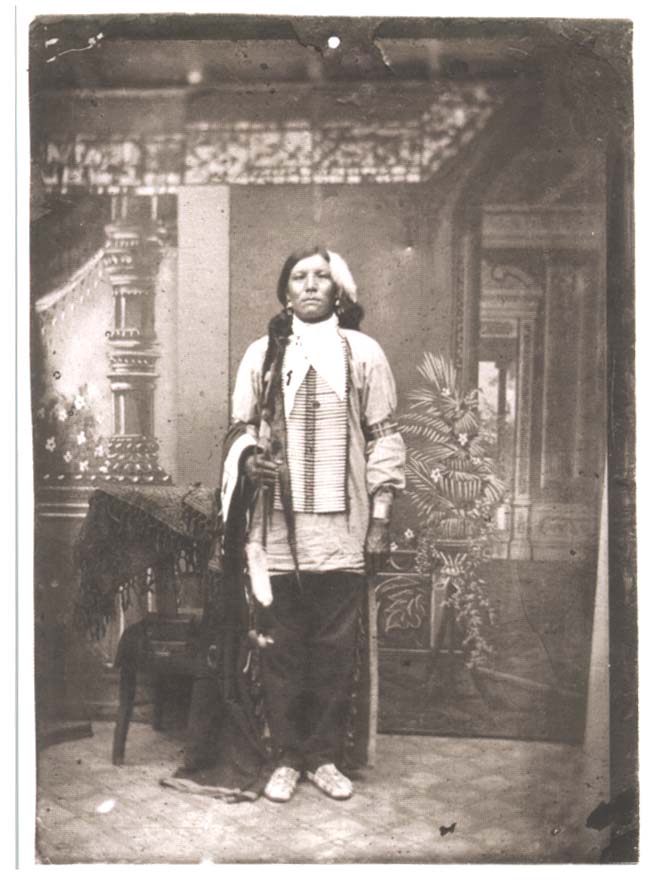

quote:“What’s your name, kind girl with the pretty face?” A younger Flash may well have succeeded at this, but that was before decades of wear on him & further genocide by the Americans. quote:Of all the infernal luck. Womanly sympathy one minute, and the next she was battering me because her rear end of a brother had got himself killed against Crook. I struggled with my yoke and scrabbled my feet in what I hoped was a coaxing, reasonable way, but she never gave me another look, and presently went out again.  And that kicker with the ugly look can only have been: author's note posted:... Crazy Horse. While the one unauthenticated photograph of him is too vague for comparison, Flashman’s description tallies fairly well with others, and the design of the medicine shirt puts the wearer’s identity beyond question; it corresponds exactly with the shirt belonging to Crazy Horse which was presented by Little Big Man to Captain John G. Bourke of the 3rd Cavalry, the well-known Indian authority and historian. (See Bourke, Medicine-Men.) quote:I got no breakfast that morning, either. Possibly on Jacket’s instructions, possibly because she was still peeved at me, Walking Blanket Woman didn’t look near for several hours, by which time I could hear all the bustle and stir of the great camp – voices and laughter and kids yelling and a bone-flute playing and dogs barking, and the smell of kettles, and me famished. Even when she arrived she was decidedly cool and wouldn’t remove my gag; it was only by piteous eye-rolling and head-ducking that I got her to relent sufficiently to pour water over my gagged mouth, so that I could obtain some refreshment. She raised no objection when I humped my yoke over to the flap, and took a cautious peep at the outside world. We'll leave him to his questions and observations and pick up with a musical interlude... next time!

|

|

|

|

Like the build up to the mutiny, just a slow fuse burning towards disaster for ol GAC.

|

|

|

|

quote:The hawk stoops, but in the grass It's like I'm there. quote:Somewhere on the right, away towards the Hunkpapa circle, there was a soft mutter of sound, a rustle as of distant voices growing, and then a shout, and then more shouting, and the low throb of a drum. People began to move up that way, the braves first, the women more slowly, calling their children to them; voices were raised in question now, feet moved more quickly, stirring the dust. The hum of distant voices was a clamour, rippling down towards us as the word passed, indistinct but of growing urgency; crouched under my yoke just inside the tipi, I wondered what on earth it could be; Walking Blanket Woman pushed past me – and then from the trees up to the right there was a scatter of people, and I heard the yell:  Looks like an overly literal fellow. quote:Across my front braves were hurrying upstream. One young buck was strapping on two six-guns as he ran, and a girl hurried after him with his eagle feather; he was shouting as she thrust it through his braid, and then he was away, and she standing on tiptoe with her knuckles to her mouth; two more braves I saw tumbling out of a tipi, one with a lance and his face painted half-red, half-black, and an old man and old woman hobbling behind them, the old fellow with an ancient musket which he was calling to the boys to take, but they never heard, and he stood there holding it forlornly; another old woman hurried by with a small boy, the bundle she was carrying burst open, and they both paused to scrabble in the dust until the kid shrieked and pulled the old girl aside as a thunder of hooves came from my left, and out from beneath the trees came as fine a sight (I speak as a cavalryman, you understand) as one could wish – a horde of feathered, painted braves, lances and rifles a-flourish, whooping like bedamned. Brulés and Minneconju, I think, but I’m no expert, and then there was another yell somewhere behind my tipi, and by humping out for a look I could see another mob of feathered friends making for the river, too – Oglala, I fancy, and everywhere there were braves on foot, with bows and rifles and hatchets and clubs, racing towards the sound of the firing, which was growing fiercer but, I thought, no nearer. Fraser's imaginary imaginary dialogue is again a treat. Well, the cavalry's arrived and everything is chaos, let's see how this proceeds... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:Walking Blanket Woman was beside me in an instant. We both stood staring over the trees. The bluffs were empty – and then on their crest there was a movement, and another a little behind, and then another, tiny objects just above the skyline, slowly coming into view – horsemen, and one of the foremost carrying a guidon, and then a file of troopers, and I could make out the shapes of fatigue hats – ten, twenty, thirty riders, and as they rode at the walk, the piping was clear now, and I found the words running through my head that the 8th Hussars had sung on the way to Alma: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgmZoqswQiA Not since Elphy in book one has Fraser so chronicled the doom of one man and it isn't until the final book that he will surpass this. quote:Perhaps I’m a better soldier than I care to think, for I know what I thought in that moment. My first concern should have been how the blazes to get across to them, but possibly because it was a long, steep way, and there was a young lady beside me at least toying with the notion of putting her knife-point to my ear and pushing, it seemed academic. And the instinctive order that I would have hollered across that river was: “Retire! And don’t tarry on the way! Get out, you bloody fool, and get out fast while there’s still time!” Goddammit, he's done it again! Not that he cares, but the why's a bit funny too. Author's Note posted:Walking Blanket Woman, the Oglala girl, fought at Little Bighorn. She rode in full war-dress, carrying the war-staff which her brother had borne on the Rosebud. (See Custer’s Fall, by David Humphreys Miller, 1957.)  quote:Well, I couldn’t reply with my mouth full of gag, and by the time I’d torn it out she had gone, running off to the right with her hatchet and knife, God bless her. And I was cool enough to drain a bowl of water and chafe my wrists while I took in the lie of the land, because if I was to win across to Custer in safety it was going to be a damned near-run thing, and I must settle my plan in shaved seconds and then go bull at a gate. And off he flies on the back of hilarious misunderstanding. quote:Apparently under the impression that I was one of the lads. The three Cheyenne were moving well, too – four of us going hell-for-leather, more or less in line abreast, three in paint and feathers, waving lances and guns, and one in white tie and tails, somewhat out of crease. Possibly they, too, thought that I belonged to the elect, for they didn’t so much as spare me a glance as we converged on the ford.  Well, he got where he was going, let's see how it leaves him. Oh, and as for the three other Cheyenne: Author's Note posted:This passage substantiates one of the most cherished traditions of Little Bighorn: that four Cheyenne warriors – Bobtail Horse, Calf, Roan Horse, and one unidentified brave – advanced to the river alone to oppose Custer’s five troops. Some versions say they took cover behind a ridge, and were joined by a party of Sioux, who helped them to check Custer’s advance by rifle fire. One theory is that Custer, unable to believe that four men would ride out against him unsupported, halted and dismounted because he expected a large force to be following the four. It is fairly certain that Custer did halt and dismount, for whatever reason, and there are those who believe that if he had continued to advance he would have won across the ford and possibly overrun the village before Crazy Horse and Gall, who had been fighting Reno upstream, had regrouped. Again, some versions have Custer actually reaching the river before being forced back; one belief is that he himself was killed there. These are matters of controversy; the one thing that now appears to have been settled is the identity of the fourth mysterious Cheyenne.

|

|

|

|

quote:For a second he stared speechless, as well he might; then he said “Good God!” quite distinctly, and I replied at the top of my voice: Always depressing when the sensible are drowned out or overruled. quote:It must have been obvious to anyone who wasn’t stark mad. But Custer was red in the face and roaring; he swung his hat and yelled at me.  Not that Flash knew Wellington well but he shook the man's hand. quote:It’s a simple, tactical thing, and for those of you who ain’t sure what turning a flank means, it’s a fair example. See on the map – we had to make for the hill marked X, with half the Sioux nation coming up from the ford at our heels. If they’d simply pursued us straight, we’d likely have reached it, but Gall saw that the crest between the bluffs and the hill was all-important, and as soon as we were out on the Greasy Grass slope he had his warriors pouring up the second coulee in droves, nicely under cover until they could get high enough up to emerge all along the line of the second coulee, especially at the crest itself, where they could hit at I and L troops, and be well above Custer’s three other troops making for the hill. Smart Indian, fighting the white man in the white man’s way, and with overwhelming strength to make a go of it. In the meantime his skirmishers coming up on us from the river were pressing us too hard to give Custer time to regroup for any kind of counter-stroke. He couldn’t charge downhill, for even if he’d scattered our pursuers he’d have been stopped by the river with Keogh’s folk stranded; all he could do was retire to the hill with Keogh falling back the same way.  Author's Note posted:Flashman’s map of Little Bighorn is erratic in details – the course of the river, and the placing of the various tribal camp circles – but agrees with most authorities in showing Custer’s advance along the bluffs, down Medicine Tail Coulee to a point near the ford, and then north up the Greasy Grass slope in an attempt to reach the hill marked X, where the remnants of his force were caught between the Indian charge from Gall’s Gully and the encircling movement of Crazy Horse’s cavalry. The underlined names (e.g. CUSTER) show where the various troops died with their commanders. A very rare visual aid from within the book itself, and almost unneeded considering the skillful description. Flash would also explain an elaborate flanking maneuver in Mountain of Light, but that was done by a badly outnumbered force instead of to one. quote:“Steady!” roars Custer. There he was, shoving rounds into his Bulldog and firing coolly, picking his men while the arrows whizzed round him. “Fall back in order! Close on C Troop!” Beside him a trooper with the guidon staggered, an arrow between his shoulders; Custer wrenched the staff from him and plunged uphill; I scrambled up beside him, swearing pathetically as I fumbled shells into my revolver – and for a moment the firing died, and Yates was beside me, yelling something I couldn’t hear as I staggered to my feet. 'In at the death.'

|

|

|

|

quote:“Hoo’hay, Lacotah! It’s a good day to die! Kye-ee-kye!”  Author's note posted:This clarifies, if it does not settle, one of the controversies of Little Bighorn – where and how Custer himself died. Indian accounts of his death have been so varied as to be almost useless; he has been killed by many different hands, in several places, including the ford at the very start of the battle. If that were true, then his body must have been carried almost a mile to where it was found on the site of the “Last Stand” on the slope below the present Monument, which seems highly unlikely. Flashman’s account suggests that he died on the spot where his body was found, and indeed where the greatest concentration of 7th Cavalry appear to have been killed in the final desperate struggle, with the remnants of Yates’s, Tom Custer’s, and Smith’s three troops scattered down the north side of the long gully below. It is worth noting, though, that Flashman’s recollections are (not unreasonably) somewhat confused; in what he calls the “slow moment” he saw Yates and Custer together; in the hand-to-hand combat that followed, the fight must have surged some distance uphill to the point where Custer died, since Custer’s body and Yates’s were found about three hundred yards apart. One point at least may be regarded as settled; however he died, Custer did not commit suicide. A rare loss for words. quote:He shoved hard at Butler, who turned and slapped the neck of a bay horse that was lying among the troopers; it came up, whinnying, at his touch, and as Butler grabbed the reins he came face to face with me, and he must have seen me at Fort Lincoln, for he said: Author's Note posted:Sergeant Butler’s body was discovered, alone and surrounded by spent cartridges, more than a mile from his own troop’s last stand. This has been one of the mysteries of Little Bighorn. The explanation that he had been despatched, when all was obviously lost, to carry word of the disaster if not to get help, is one that must have occurred even without Flashman’s corroboration. Butler was, after all, a trusted and experienced soldier, and no one in the regiment would have been more likely to win through, a point acknowledged by the Sioux themselves. Sitting Bull, Gall, and many others paid tribute to the courage with which the 7th Cavalry fought its last action, and singled out some for special mention, but above all the rest they praised “the soldier with braid on his arms” as the bravest man at Greasy Grass. Fraser seems to regularly give the men at the action the more favourable death that they may have suffered according to best historical guesses. quote:All this I took in during one long horrified second – it couldn’t have been longer or I wouldn’t be here. I doubt if I even checked stride, for one glance behind showed a dozen mounted braves and a score running, and they all had Flashy in their sights. To the left and below the slope was thick with the bloodthirsty bastards – all you can do is see where the enemy are thinnest and go like hell. I swerved right in full career, for there was a break of perhaps ten yards in the mob surging up to join in the massacre of Custer’s party. I went for it, sabre aloft, bawling: “I surrender! Don’t shoot! I’m not an American! I’m British! Christ, I ain’t even in uniform, blast you!”, and if anyone had shown the least inclination to say: “Hold on, Lacotahs! Let’s hear what he has to say”, I might have checked and hoped. But all I got was a whizzing of arrows and balls as I tore through the gap, rode down two braves who sprang to bar my path, cut at and missed a mounted fellow with a club, and then I was thundering down the right side of the gully towards the group on their sorrels – and they weren’t there! Nothing but bloody Indians hacking and stabbing and snatching at riderless beasts. I tried to swerve, aware of a mounted lancer coming up on my flank, a painted face beneath a buffalo helmet; he veered in behind me, I screamed as in imagination I felt the steel piercing my back, hands were clutching at my legs, painted faces leaping at my pony’s head, my sabre was gone, an arrow zipped across the front of my coat, something caught the pony a blow near my right knee – and then I was through the press, only a few Indians running across my front, when an arrow struck with a sickening thud into the pony’s neck. As it reared I went headlong, rolling down a little gully side and fetching up against a dead cavalryman with his body torn open, half-disembowelled. Author's note posted:Flashman’s ride clean across the battlefield, from the point where Keogh’s troop fell until he must have been close to the river, might seem improbable if it were not corroborated by an unimpeachable source of which Flashman himself was probably never aware. In a magazine article published in 1898, the Cheyenne chief Two Moon, who played a leading part in the battle, and is regarded as one of the most reliable Indian witnesses, had this to say of the final moments of the struggle: All over but the clatter. Let's bring this chapter to an end... next time!

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 7, 2024 04:10 |

|

quote:...for directly behind it Custer was falling, on hands and knees, and whether I’d hit him, God knows again. Goddamnit Flashy.

|

|

|

i like nice words

i like nice words