|

I'm sure that's fine.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 3, 2024 16:07 |

|

Only good things happen to people nearby the Caliphate during its early years, I'm sure.

|

|

|

|

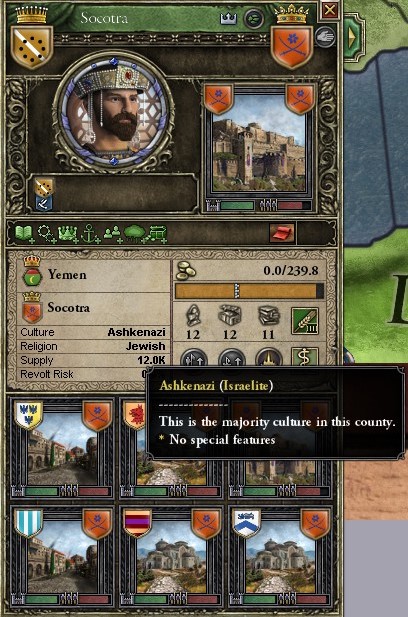

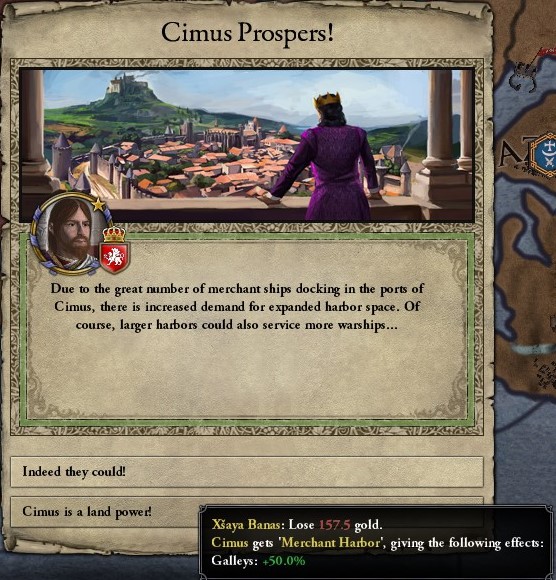

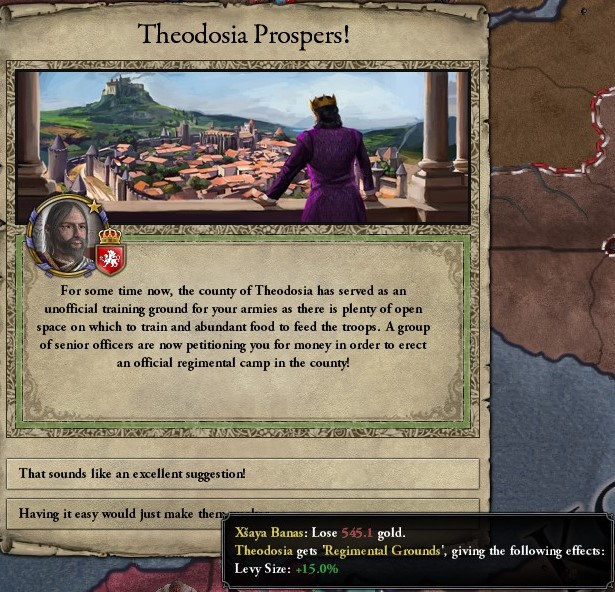

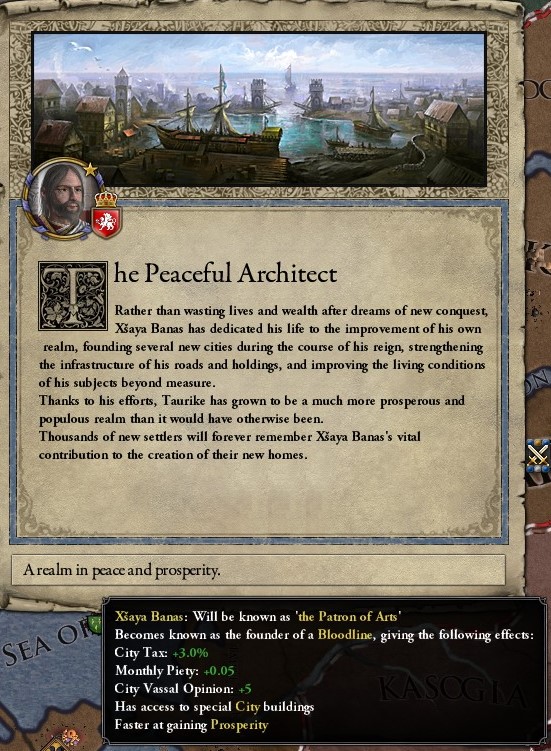

23: Fitna The sudden ascendancy of the Caliphate from the Arabian peninsular upended the decrepit economies of the Mediterranean, which had been brought to their knees by the Slavic invasions in the East and the Germanic hordes in the West. Stretching from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean in the West by the time of the Prophet’s death, the merchants of the nascent Islamic world brought goods from Indian markets long cut off by the Turkic invasions. The island of Socotra saw particular investment by a Mizrahi merchant family, who brought many of their co-religionists over to see to the harvesting and sale of the island’s dragon blood  I need to switch it over to Mizrahi via console, but most of the symbols are permanent modifiers from prosperity - Socotra has a grand harbour, monuments, and a magnificent library For Banas and the Taurikian court, the Islamic ascendancy meant one thing: wealth. Furs, honey, and slaves could all be procured (by force or by ‘trade’, although the two often blurred into each other) from the inhabitants upstream on the Rahā and the Silys. Travelling downstream, any merchants wishing to depart from Taurike would face stiff tolls and tariffs for the privilege - a cost which they expected to recoup many times over once they docked in one of the newly rejuvenated ports of old Phoenicia or even Aegypt. In Taurike, Banas and his wife Delbar flaunted their wealth, hosting feast after feast for the nobles and notables of the realm.  Outside of the royal court, the newfound wealth was put to more productive purposes. The swamps of Cimus had long been a dwelling place only for desperate peasants and outlaws seeking refuge, with distant nobles in the capital showing little interest in local affairs provided the monthly tithe of eels was paid on time. With maritime traffic increasing along the shoreline, many coastal villages sought to lure merchants to their shoes, constructing rock piers and dredging harbours. Further inland, other headsmen set their villages to draining swampland and began to experiment with the cultivation of crops beyond the common rye and barley. The most notable crop in the region rapidly became raspberries, long popular amongst apothecaries for the medicinal properties of their leaves, but yet more popular amongst sailors for the heady wine brewed from their berries.  In the capital itself, a swath of new constructions were springing up around the royal keep. The Yarkarmii fortress had long been the only stone construction of note in the capital, but was now joined by a host of lesser buildings incorporating arches and buttresses, some even spanning multiple stories above the ground. In their shadows, the venerable Yudkaeveon seemed an antiquated relic from a simpler time - a perception only heightened by Banas deciding to expand his own keep, turning much of the ground floor into a spectacular hall to host his incessant feasts.  The growing power and wealth of the Caliphate was beginning to cause friction within the Prophet’s own household. Ghalib, as the Emir of Babylonia, one of the richest conquests of the Caliphate, had been the clear successor to the Prophet on his death, being one of the most powerful men in the Caliphate and the only adult son of the Prophet at the time. His ascension had met with some disgruntlement from his half-brothers and their mothers, and a band of malcontents had gathered behind one such claimant, Alim. .jpg) From the distance of Taurike’s ports, the party of Alim seemed to be a fool’s errand - lacking a regional powerbase, money, or troops. In the Arabian lands, however, it was a deadly threat - an attempted assassination of Caliph Ghalib was only thwarted when his secretary threw himself on the poisoned sword, and witchhunts for other would-be plotters paralyzed the Holy Cities over the customary Hajj season, with pilgrims attempting to make the journey to the Kaaba turned back by armed guards. Alim managed to flee the city just in time to escape capture, re-appearing in Babylon where he travelled from town to town preaching on the necessity of a Caliph being virtuous and pious, and the alleged duty of Muslims to ensure his father’s successor was worthy of his role.  In a region where many notables remembered their independence well, Alim’s message found willing listeners, especially amongst the growing numbers of Muslim converts from outside Arabian clans, who found themselves disgruntled at their continued second-class treatment in the Caliphate’s administration. When the Alim’s pursuers arrived in Mesopotamia, they found themselves repulsed by force in a mass uprising, and had to settle for pillaging the sugar plantations outside the main cities, kidnapping or killing the slaves owned by the Shīʿat ʿAlīm - the partisans of Alim. Such successes for Alim were inevitably temporary - although the Arabian desert meant the Caliph’s army could not immediately cross the desert to attack him, the sight of ships flying his brother’s banner spanning the breadth of the Persian Gulf proclaimed his inevitable defeat.  With his followers melting away and surreptitious messengers from them leaving Babylon every evening to beg for terms from his brother, Alim elected to flee, abandoning Babylonia and crossing the Bādiyat Ash-Shām before his brother’s forces had even emerged from the marshes of southern Mesopotamia. Emerging from the desert in the modest trading town of Damascus, he and the few soldiers he had retained the loyalty of chartered merchant ships, electing to sail to distant western shores over his certain doom should he remain in the Islamic world. In doing so, Alim wedged the first cracks into the foundation of the Dar-Al-Islam, planting the seeds of the first Islamic society outside the Caliphate - but that is a tale not fully written.  For the Taurikan merchants and toll-setters, such chaos in the Caliphate only ended rebounding the more profit - as the Caliph’s forces carried out brutal reprisals in Babylonia, stripping former Babylonian lords of their lands and titles in favour of new Muslim landholders from the Arabic soldiery, the market for slaves exploded. Canals abandoned during the fighting needed re-dug and dredged, fields left fallow required stripping and replanting, and the ever-thirsty lands of the sugar cane required their tithe of human blood regardless of who owned them, a harvest the Taurikans were more than willing to cull from the tribesmen of the north. In Cimus, some of the peasantry who had begun to court merchant travelers decided to cut out the middlemen, turning slavers and merchants themselves rather than merely seeking to host them. An expansion of the hitherto modest Scythian shipbuilding arts then followed, with accomplished carpenters being able to name their price to a growing middle class.  Manicheans and Muslims were not the only ones reaping the boon of the growing maritime mercantile world - the anointed ones, Christians, had long held a near monopoly on long distance trade. While the ascendancy of Muslims and the increase in Scythian merchants had disrupted some of their traditional monopolies in the east, their connections with their Gallic co-religionists gave them unrivalled influence in the west, where demand for incense and spices from the Caliphate remained high.  By comparison, pagan merchants were shunned in both Scythian and Muslim lands. Indeed, the one war waged by Banas in his reign was against the Iazgians to the east - the traditional targets of Taurikian expansionism, a slave raid downriver against tribesmen under Taurike’s protection drew a punitive expedition from Neapolis, with the merchants being driver back further from the river and their camp pillaged and sacked.  Such a hostile approach (not to mention extremely hypocritical - merchants sailing upriver from Taurikian ports had committed far worse raids) to paganism was doubly the case in the Caliphate. Not only was the Caliph constantly pushing his borders further outwards in incessant wars against the pagans, but the act of shirk, or polytheism, was dealt with harshly. While by necessity the Caliphate tolerated some idolatry among the larger peasantry, the harshest punishments awaited a nobleman who was found to be practising polytheism in any form, especially if they had professed Islam beforehand, making them not only a polytheist but an apostate. Matters in Mecca came to a head when the Caliph’s own son was discovered in a band of men offering animal sacrifices in the traditional manner to the old Arabic pantheon, and no mercy was given on the basis of family ties - the entire band was impaled on stakes mounted along the road as warning to all other notables contemplating shirk.   While Banas never turned to executing his family (although the quantities of wine served at his feasts could approach lethality), he had always been distant from his father, a man of the wild northern frontier who preferred the hunt to the feast. His death at the age of 80 testified to his vigorous health, but left Banas the nominal lord of an unmanageable expanse of land to the north, much of it unmapped and lacking roads or any real understanding of the territories outside the few established settlements along the river’s side. With little interest in governing or seeing the lands for himself, Banas decided to summon the council to plan the succession of the kingdom and disposal of his newfound inheritance. Such a gathering, of course, called for a grand feast.  At the council, the notables of the land heartily endorsed Banas’ disposal of his inheritance to his brother and nephews, fearing the concentration of land and power in a single line of the family. The matter of succession was more contested - the newly wealthy merchants made no secret of their preference for someone who would continue Banas’ ‘wise administration’ of the realm, rather than a warrior-king or queen who would squander the realm’s taxes in wars against the pagans, with all the taxation and diversion of trade that would imply. In the end, the council settled on the favourite of the elect - Nauakos, grandson of Banas and lord of a minor settlement past the mouth of the Silys. A quiet, reserved man who had attended enough of Banas’ feasts to give himself gout without ever making a real impression on anyone, Nauakos had pleased those attending with his understanding of Manichean cosmology and apparent dullness in all other matters.  Perhaps stung by the merchant’s association of his reign with a lack of action against the pagans, complimentary as it had been intended, Banas spent the years after the council re-organizing the Taurikian levy system, establishing a chain of messenger ports along the peninsular to act as waystations for levies called up to assemble before sailing to the capital. Never tested in his reign, they were later to prove useful, albeit in need of some modification (most notably, accommodation for the troops should the weather bar an immediate departure), in the future.  Despite such investments, Banas departed the world with his reputation amongst the merchants as a bringer of peace and prosperity fully intact. His funeral feast was, appropriately, one of the largest Neapolis had ever seen, with some prominent families sponsoring free meals for the common folk of the city over a 2-month span in his memory.   Nauakos took the throne as a somewhat unknown factor for both the nobles and the merchants of the realm. Less interested in feasting than his grandfather, he instead put the royal treasury towards a renovation and expansion of the grand Manichean temple, the Yudkaeveon. In short order, he picked up a reputation among the capital as a pious and upright believer in the Light.  While his zealotry was often overstated by his courtiers and sycophants, Nauakos had a notable disdain for both pagans and Christians, a disdain only heightened by his marriage to a convert from a Christian family who was some 20 years his senior. A strategic marriage contracted well before any hint of his elevation to the throne, the marriage had been a cold one since the beginning. In particular, Nauakos had taken to lambasting his wife’s failure to give him a son, and showed little interest in his only daughter, leaving her in the care of the castle guard most days.  Unlike Christians, Muslims and their traders remained welcome in Taurike. Many of the lesser nobility mounted expeditions to the Caliphate, seeking glory and wealth on the battlefields of the south for as long as Taurike’s swords slumbered in their scabbards. Their service was eagerly appreciated in the Caliph’s armies, but as the Caliphate expanded the role of foreign mercenaries and adventurers began to wane, with the Caliph preferring to staff his bodyguard with Arabic Muslims over foreigners loyal more to money than faith.  The Caliph wasn’t the only one attempting to restructure a society along religious lines - to a lesser degree, the slavic and germanic tribes to the north-west of Taurike were going through their own reformation. Being too far upriver for Taurikian slave raids, they had long been partners in the lucrative amber trade which dominated the long-distance trading of the Baltic coast. With the restrictions placed upon ‘pagan’ merchants serving to lock them out of Taurikian markets, they began to model themselves as servants of enlightenment, taking up patterns and motifs left by the long-extinct Wusun kingdom. While such enlightenment often sat uneasily alongside animal sacrifice and ancestor veneration, it was often sufficient for Taurikian merchants to claim that they were preferable trading partners to the rest of the ‘barbarians’ to the frozen north.  The rites and rituals of Scythian Manicheanism were, of course, far grander than any barbarian of the north could hope to emulate, enlightened or no. On holy days, such as the anniversary of Mani’s death, all of Neapolis thronged in the streets to watch grand processions of eunuchs, prefecti, and pious nobles make their way around the capitals winding streets, ending up where they had started at the Yudkaeveon. Packed inside, a traveller would see fine artwork depicting the realms of light as illustrated by Mani on the walls and ceilings, all shimmering and shifting in a thick haze of incense. Nauakos would be found up the front, a figure listening intently to the sermon being pronounced.   Such splendour - surely a foretaste of the eternal realms of light in a fallen world - could not fail to impress, and even the peasantry of the realm were won over piece by piece, with monks and preachers trained in the capital sent out to impress upon the rural labourers their duty to serve the elect and their servant, the Xsaya, in hope of being born again in the next life as a elect themselves. West of Tanais, entire tribes of Hungarians were won over the light, with the traditional altars smashed or converted into Manichean shrines for the use of the elect of Mani.  By contrast, Frenay, the Xsaya’s daughter, was rarely seen in services, or even in her father’s presence. Taking after the warrior-queens of Taurike’s past, her time was spent drilling with the palace guard or arguing strategy with the river-captains charged with keeping the waterways of the kingdom free of (foreign) pirates. When she came before the court to plead for command of her own, her father granted her his only real gift - a small fleet of riverboats with the men to crew them, and permission to leave the capital to cleanse the rivers of bandits.  Frenay’s raids against pirates proved a rapid success, and trade to the Caliphate continued to increase, with Nauakos sanctioning the construction of a mosque and a modest merchant’s quarter around the docks of Neapolis - albeit one which was prominently outside the city’s walls.  With such close ties to the Caliphate, Taurike was one of the first locations to hear the news of Caliph Ghalib’s death at the age of 68. Having fought off his brother, brought much of Galatia and Aegypt under Islamic rule, and sired many sons, Ghalib passed away in his sleep. With the last son of the Prophet dead, the Islamic world passed into the hands of those who had never met the Prophet while he walked the earth - a small shift, which passed like the breeze from a final breath. Half an ocean away, such a breeze blew over the waves crashing on the shores of Malta, where a nephew in exile was brought news of his hated uncle’s death.  The world in 684:

Yuiiut fucked around with this message at 09:21 on Apr 4, 2024 |

|

|