|

That went downhill quickly. Edit: update on last page

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 3, 2024 18:51 |

|

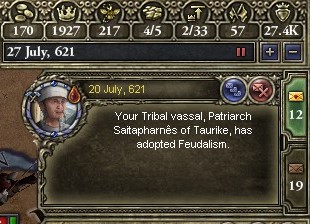

Iceblocks posted:Good to see you back. Bits and pieces of Plus - mainly the faction system - and a fair bit of WTWSMS for cultures/religions (speaking of, Manichean is diving for the floor in terms of moral authority right now, and may hit single-digits soon) Also, a fun discovery I made - the Parthian king died in battle resisting the Dahae confederation, which is tributizing Parthia. The throne has passed to his daughter, as he seemingly lacked any sons - until 3 months after his death, when his mistress, a nun, gave birth to his bastard.

|

|

|

Yuiiut posted:(speaking of, Manichean is diving for the floor in terms of moral authority right now, and may hit single-digits soon) I mean we did vote to follow it, which by extension technically makes it a goon project and thus doomed to fail.

|

|

|

|

|

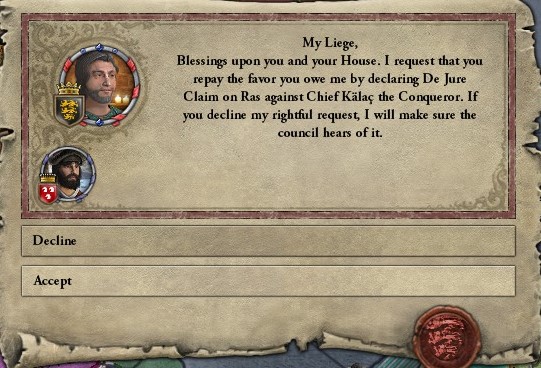

well it was a fun experiment, back to the old gods!

|

|

|

|

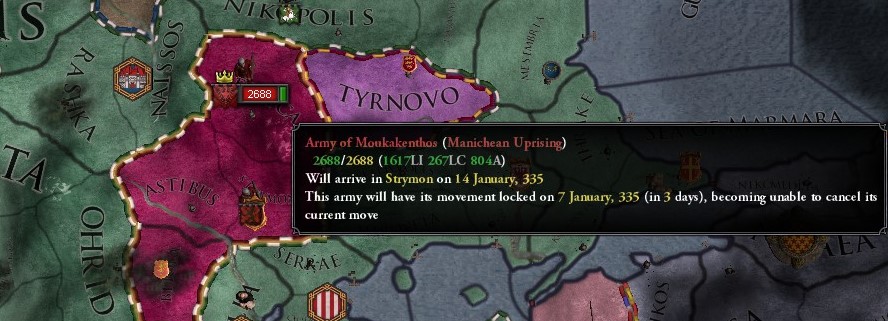

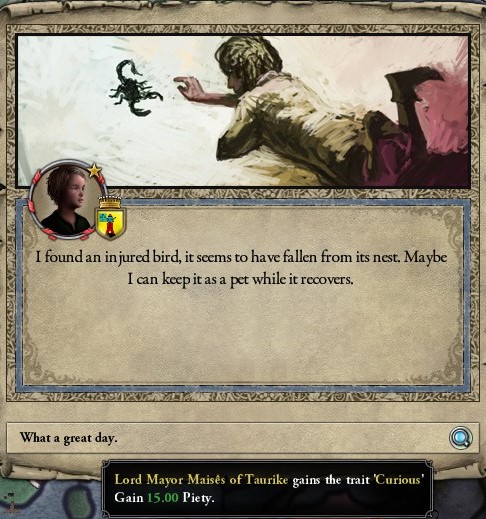

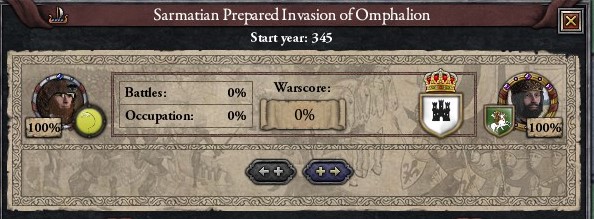

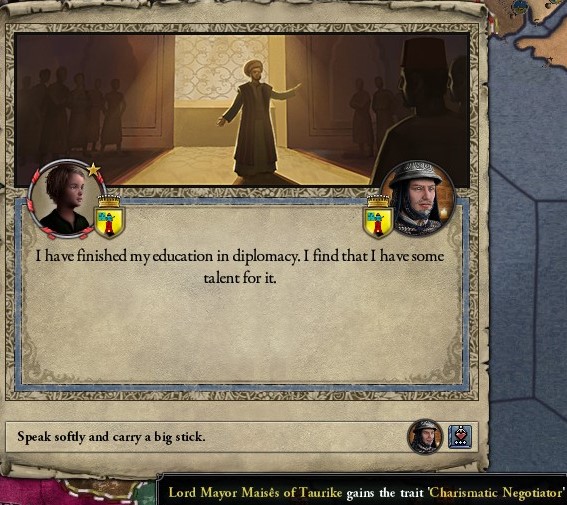

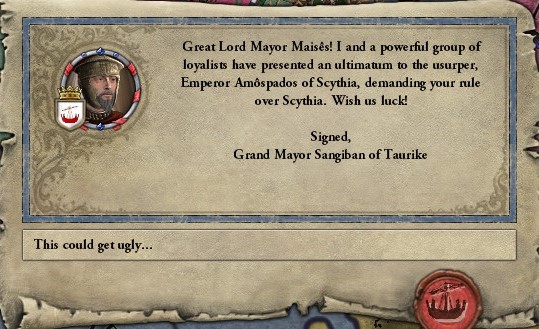

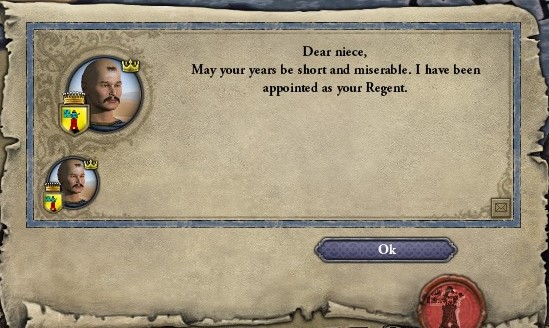

16: Lonely as a cloud: Maises in exile Taurika and the grand old capital at Neapolis had long been the refuge of the Yarkarm family, and it was to their ancestral seat now that Areange - widow to a murdered husband, mother to three children whose continued existence was a threat to the new ‘High King’ - fled. Never one to stand up for herself or stand out at court, she was nonetheless fanatically devoted to her children - Maises, Stormais and their sister Saruke - and possessed of a canny political streak.  Portait of Areange as regent, silver coin, 330AD Landing in Neapolis, she proclaimed herself regent for the infant Maises, buying the town’s loyalty with a debt jubilee and a spate of tax exemptions for local notables, buying her time to negotiate with the Cimus forts’ garrison, who swore for her shortly afterwards. With her local position secured, she felt safe to ignore the ‘High King’s’ pronouncement of a Pellan nobleman as the ‘Lord of Taurike’, and indeed Godigasos would live out his days in Pella, content to dine out on his nominal title without ever actually trying to set foot on the peninsula.   Game mechanics mean that we, and every other republic, have turned into a republican vassal of Scythia as our own bespoke republic, making the internal borders and politics a complete and utter mess It was in this strange political environment that Maises and Stormais were raised in - their mother ruling on their behalf, but fearful the hammer could fall at any moment on their precarious kingdom. Fear of assassins meant visitors from the rest of Scythia or other lands were few, and news travelled slowly, not helped by the turmoil inland - pogrom and counter pogrom breaking out between Christian and Manichean villages, which the High King battled valiantly, yet unsuccessfully, to quell.   The pink duchy was formed via Christian peasant revolt, lost to the Manichean revolt pictured, which then lost to a Christian counter-counter revolution at a later point Tucked away in Taurike, Maises must have been cripplingly lonely and isolated at such a tender age - shunned by fellow nobles, his only real companions where the handful of trusted servants waiting on Areange, along with stray animals.  Admittedly, not all of Maises’ isolation was outside his control  Birds have the significant advantage of not seeking to kill you to curry favour with the High King This shy, reclusive child - theoretically, a claimant to the Scythian throne - was thrust into adulthood and responsibility unexpectedly. While Areange’s paranoia had protected her family from blade and poison, a more insidious killer struck. At the age of 10, Maises was called to her chambers by the local priestess, as typhus had robbed her of the ability to stand. Apocryphally, she had him swear on his father’s soul that he would avenge his father, and see his killers punished. While such details smack of embellishment by later chroniclers, what is known is this would be their last conscious meeting. Areange - a daughter of a minor Gothic chiefdom, plucked from obscurity by Nandake in what was possibly his only good decision - died 2 weeks later, at the age of 30. Maises, at 10, was left with his two younger siblings as his only family in the world.   The province of Sarmatia had long prized its autonomy and independence from the Republic, and had ignored all demands for tribute from the new ‘High King’. In 341, the year after Areange’s death, they made their move - pouring over the border, their warriors taking possession of Taurike as the first step in a grand invasion of the Republic. Maises was set aside by them but otherwise left unharmed, considered a potential pawn for the future but otherwise irrelevant.   As the Sarmatians moved further south, crossing the Dniester in the spring of 343, the Romans declared in support of them, marching on Scythia from the West, seizing and burning villages as they did so.  The worst was yet to come, however. With the garrisons unmanned or torn down by the advancing Sarmatian host, the Slavic tribes flooded across the northern border en-masse, travelling southward to the Peloponnese. While the armies King Mauros could raise were substantial, they could not be in three places at once, and his hopes of keeping the throne - or his head - seemed to be ebbing away.   Maises, ‘ruling’ Taurike in the 5th year of the Sarmatian occupation, was not overly concerned by the High King’s plight. His haggling with the Sarmatian garrisons had given him a reasonable education in negotiation, albeit at the cost of developing a ruthless, cynical streak. With most of the real responsibilities of rulership (and most of the taxes) going to the occupying soldiers, he whiled his days hunting, feasting and womanising, most of which did little to diminish his growing popularity. However, while he was liked by all, he was loved by none - his marriage was a distant affair, and courtiers would often remark his only real friend was his hunting dog.   Such idleness could not last forever, and as the Sarmatian rule over Scythia grew, so to did the occupying forces morph into garrisons, with the bulk departing around 350, settling down south as to be closer to the court of the new ‘emperor’ of Scythia (although the Istrogoths continued to reject his authority, establishing something close to de-facto independence in the process). Taurike was left in Maise’s hands, his co-operation over the last few years (and antipathy for the former regime) standing him in good stead.  Maise’s first few years of ruling independently were haphazard, with meetings with local notables degenerating into bouts of drinking contests and feasts. Little by little, however, he grew in competence and skill, able to deflect concerns about taxes with magnificently publicised bouts of spending on grand new edifices or alms for the poor being distributed.   All the artifice and self-aggrandisement in the world, however, could not save Maise’s reputation with his wife, a shrewd Christian woman from a minor family in Pella. While the Manicheans were willing to overlook Maise’s various affairs with mystics, peasants, or courtesans, Uxshenti stewed over his flagrant unwillingness to disguise them, and the growing number of his bastards tolerated in Neapol infuriated her beyond measure.   While Maise was willing to ignore Uxshenti’s concerns with his philandering, the consequences she was predicting were proving prophetic in the court of Scythia down south. The Sarmatian emperor had been a devotee of the old ways over the monogamy preached by the monotheists (although the preaching tended to be on other topics when Maises made a rare appearance at a Manichean service), and had left a sprawling brood of children behind after unexpectedly dying at the spear-tip of a petty nobleman when putting down a tax revolt.  Blood was in the water, and the sharks were circling. Amospades, the eldest son of the emperor, was propped up on the throne, but each of the former emperor’s many wives had their preferred son, and the Sarmatian host Omra had put together in his lifetime was divided.  The nobility of Scythia outright rejected any child’s right to rule them. Beaten down briefly under the weight of the Sarmatian invasion, they had since rebuilt their armies and reaffirmed their follower’s loyalty. None of the pagan sons of the dead warlord commanded much loyalty amongst them - they wanted a true Scythian ruler, one who would respect their traditions, restore Scythia’s tattered prestige, and protect the realm against raiders and marauders. There was, of course, one immediately apparent candidate.

|

|

|

|

Here we go!

|

|

|

|

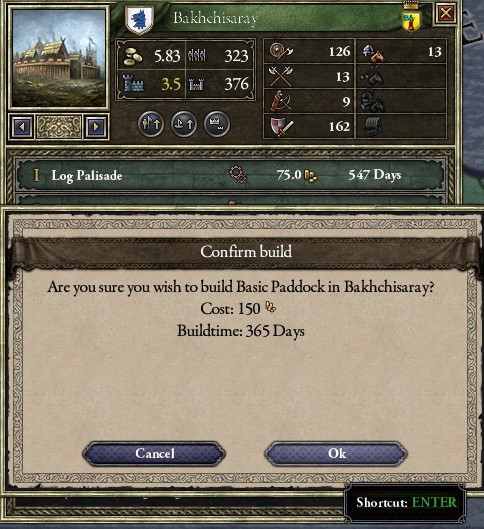

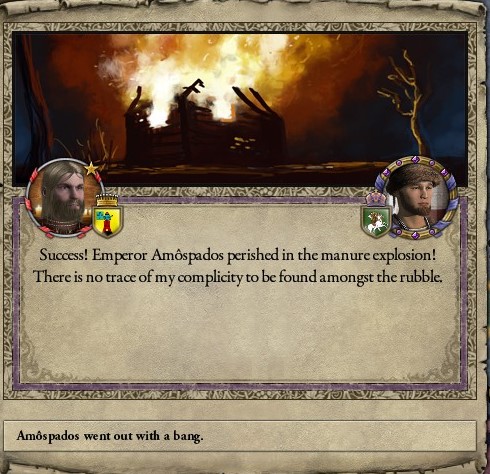

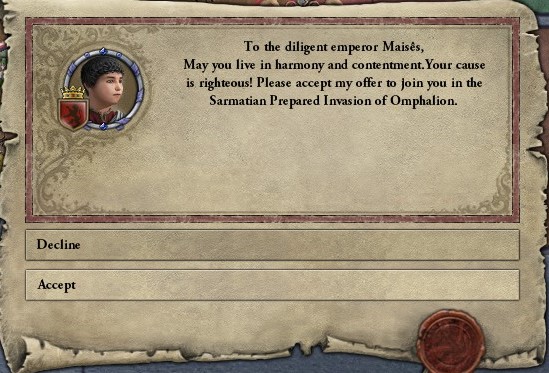

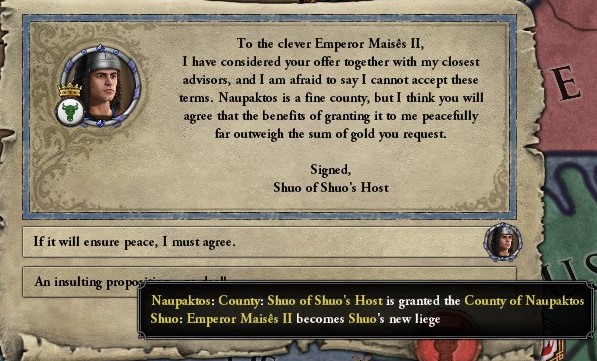

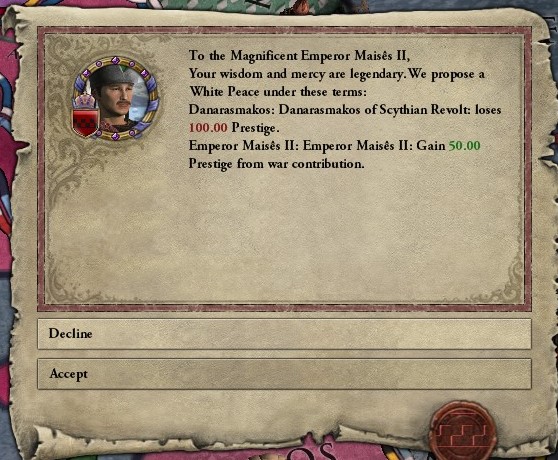

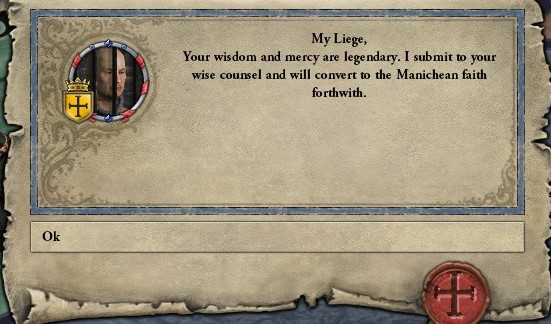

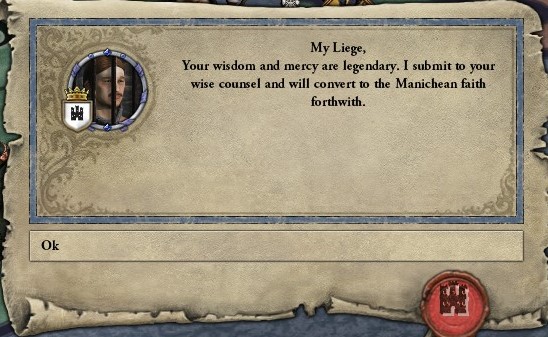

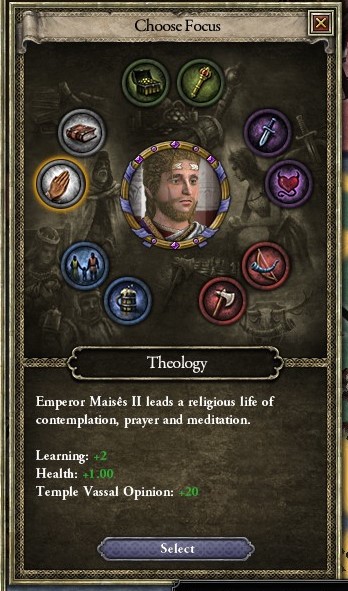

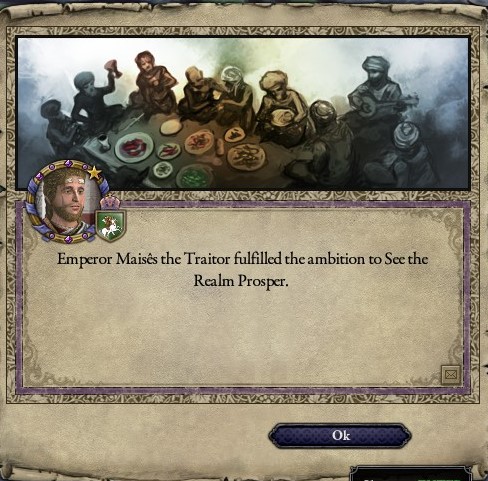

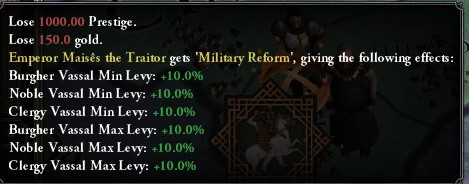

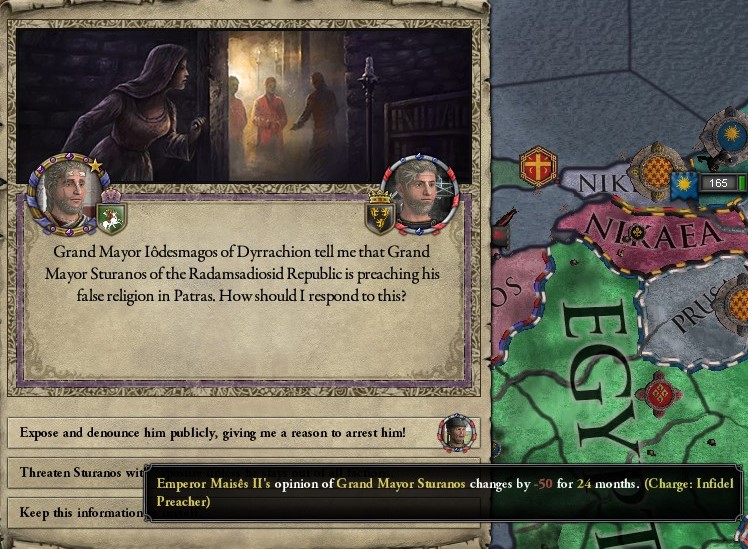

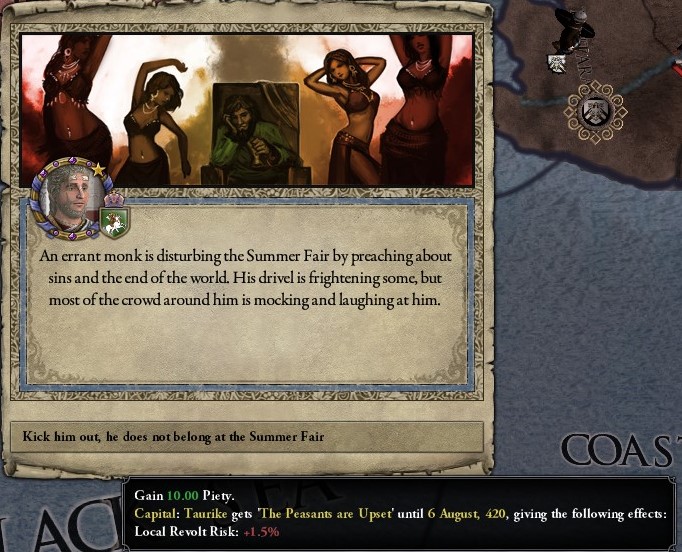

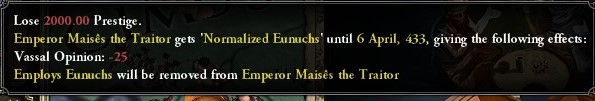

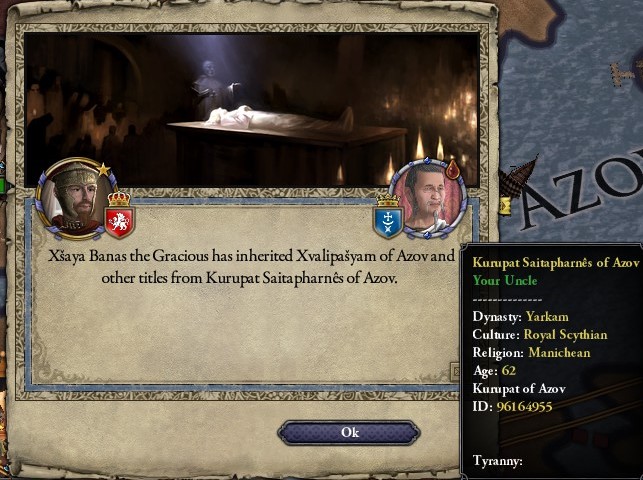

17: Swords into plowshares: the Maisian era Amospades, king of the Sarmatians and Archon of Scythia, was not one to take threats to his reign lightly, even if he was only 14. The first months of the rebellion were strangely quiet, as messengers sped by light boat along the coastline or hurried on fast horse down the dilapidated roads of the old republic, carrying with them messages which variously pleaded, cajoled, threatened or bribed the lords of Scythia to take a firm stand for either camp. In Taurike, the centre of his power, Maises summoned every able warrior he could find to his side. While some of the oldest in his court could recall a time where Scythia could marshall a host of thousands of horseman, Maises could levy a scant fivefold hundred men, most of whom were sailors or peasants - professional warriors were few amongst the ranks. Amospades, meanwhile, managed to win grudging acceptance from a host of the Scythian nobility, leaving him secure to march the Sarmatian host against the rebels.  As his army gathered in Neapolis, Maises was suddenly bereft of his brother, taken away by a fever which ripped through the camp. While the army’s departure was delayed by some weeks to see to the proper rites, Maises buried the last of his childhood in a grand tomb in the centre of the city, laying his body amongst their father and mother before sailing south. Although he did not know it, he would not return except to join them. In the present the war’s course seemed to be uncertain - Amospades had failed to decisively crush the rebels in an engagement outside out Pella, and his host had suffered significant casualties and desertions in the months which followed. The rebels were in an even worse position, having retreated behind the old walls of Pella to await relief from the north when Maises arrived. Having received word of their defeat, Maises had no plan to rush to their relief, however - they were tying down the Sarmatian warhost, leaving their camp in Kallipoli poorly defended. Storming it from the sea, he captured Amospade’s family - his brothers, sisters, and mother - and dragged them back to the ships as hostages. By courier, he sent Amospade a demand - break the siege and meet him for parley, or see them all drowned. Cowed, Amospade complied, and agreed to meet on the old mount of Athos to see his siblings ransomed.   With the tragic death of Amospade on the road to the mount - burnt in a terrible fire at a lodging house, which few wished to investigate further - the Sarmatian clause collapsed. With the rule of Scythia shakily in his grasp, Maises released the captives from his possession as a gesture of ‘reconciliation’, and set about ruling his new realm. For the most part, what ruling meant was to offer gracious gifts to the lords who had supported his cause and to host others with feasts, fairs and banquets as he toured up and down Hellas.  His personal life, meanwhile, was conducted mainly via letter and messenger. His eldest son (also known as Maises) had followed him down south with the warcamp, but the demands of rulership were to keep Maises the elder away from Taurike for quite some time, so Maises junior was dispatched to govern it in his name - though not before a lecture on the importance of diligence and prudence in administration, which he seemed to take to heart. One of the first acts as regents by Maises was to see his bastard brothers married off to foreign lands - there would be no Sarmatian succession if he had anything to say about it.   Down in Hellas, meanwhile, Maises the elder was running against the limits of his finances - the Scythian tax system had all but collapsed, and the gifts he was giving out had depleted his warchest, even after the looting of the Sarmatian court. Given his public polygamy and flouting of Manichean morals, he was an appealing liege for Jewish and Christian merchants, some of which offered him generous bribes for trade rights and ports on the terminus of the Silk Road.  There was, however, an issue. Taurike had seen much of its sailors depart south in the war. Some could never return - others simply wouldn’t, preferring the richer climes and markets found in the Mediterranean. The result had been the same either way - with few guards to protect them, merchants were suffering an outbreak of piracy and banditry. Some, rumoured to be sponsored by the Khan of the Iazyges, had gone so far as to loot and ransack Neapolis itself. The Jews and Christians were clear - if more gifts were requested, the sealanes needed to be cleared, and the pirates tracked down to their lairs and put down. Maises was only too happy to oblige - and to return to Taurike, to see his sons and daughters again.  It was a grey morning when they launched the assault - grey and bitterly cold. They’d tracked the pirates from the shore, locating their camp amid the stinking marshes without being spotted - or so they thought. When their approach was met with a hail of arrows, they knew they had been made, and the pirates were waiting for them. Still, the numbers were on their side, and Maises was leading them from the front. Hewing a foe, who fell to the side, he turned to usher them on, only for his cries of command to come to a spluttering halt as the dying man on the ground ran a spear through his side.  Maises the younger - now Maises the Second- knew what was to challenge him. An orderly succession had not happened since the start of the now-defunct republican reforms. He was determined to be the first, and set to drilling the remnants of his father’s troops and amassing funds to guarantee they could be paid steadily for years, if need be.   While the Sarmatians were clearly plotting something, the first blow to land came from the wild slavs. The chaos of previous decades had had many migrate through the Thrakian highlands, and they all poured out, moving southward to the Peloponnese and Hellas proper. An entire people on the march, they came with the old and the young, with warriors and mothers carrying infants, all seeking a new homeland. Some thousands in number, they threatened to totally overwhelm the Scythians before them. Fearful for the regional consequences if unchecked, other Manichean and Scythian lords offered Maises their assistance in stemming the tide.    The Sarmatians, meanwhile, were not one to miss opportunities in a crisis. By blackmail, bribery, and threats they were able to assemble a coalition to restore their overlordship over Scythia, and wasted no time in assembling an army and starting to pillage the countryside. Maises would have struggled to fight off the slavs with the Sarmatians by his side - with them against him, he simply did not have the men or forces necessary to deal with the crisis.   Desperate times called for equally desperate measures, and so Maises reached out to the Goths who had settled in the former lands of the kingdom of the Wusun, offering to sell them lands in the south of Hellas in return for gold and their sword-service. His desperation was palpable, and it was obvious - his attempt to leverage funds out of them was flatly rejected, and he was told the only offer they would consider would be for the lands to be gifted to their tribes outright. Desperate, he agreed.  Despite the negotiations taking an unfavourable turn for Maises, the results were spectacular. As the slavs tramped south, they found themselves met with ambushes and traps. When women left camps to forage for supplies, they would not return. If men left for a hunt in groups of fewer than 20, they found themselves set upon by gothic warriors. With morale collapsing and the civilians fleeing back north, the slavs returned to their former abodes, unwilling to leave.  I had not realised that paradox code meant if you settle a adventurer in the target kingdom, it will cancel any prepared invasion That left the Sarmatian traitors to deal with, which Maises was only too happy to do. Setting his camp in the mountains inland from Pella, he drew their horsemen out, luring them along a narrow path where an attack could be commenced by rolling boulders down at them. With the key element of their force disabled, his forces swept down on the straggling remains, picking them off as they tried to flee.  When the day was over, it seemed clear that the revolt was doomed - many of its best men lay for the crows on the mountainside, and the trajectory of the future obvious. Maises had won no small amount of credit for his actions on the battlefield, being seen as someone who victory and glory followed. When an offer for peace arrived from the Sarmatian camp, he dismissed it, proclaiming that unless they had a second army, they were doomed to suffer the fate of traitors.   Little did Maises at that point that the second army had already arrived from the sea. No Sarmatian army, this was a second wave of Slavs, coming from the isle of Krete and seeking to take possession of southern Hellas. While Maises welcomed the wave of support he attracted as a result of it, the 4000 men landing outside of Taurike and Pella were another matter.   With his Thrakian allies, Maises fortified himself inside Pella, preparing for a new onslaught. Arriving in the evening, the first act of the Koroatian invaders was to torch their own galleys, leaving them to drift towards the docks and start fires across the waterfront. As the defenders desperately sought to put out the fires, the Koroatians stormed the seawalls, seeking a beachhead. While they were successful a handful of times, each one was driven back by the Scythians, the invaders being pushed into the black waters. When the dawn broke, the harbour was choked with ash, burnt ships, and the corpses of Scythian and Slav alike - but the city stood. More surprising still, one of the captives was revealed to be the chief of the invaders, who was willing to broker peace for his life.   With true peace in the realm for the first time in many decades, Maises turned his mind to spiritual matters, acquiring a genuine interest in theological developments, long neglected under his father. Rebels were pardoned to teach ‘the mercy of Mani’ to them, and Maises took to secluding himself for long periods of prayer and penance - all of which endeared him quite considerably to the clergy.    As far as the realm itself was concerned, however, Maises commitment was only to one thing - peace. Soldiers and peasants, conscripted from their fields and dragged into battle time after time again, were released. Fairs, indefinitely suspended from fear of invasion or infiltration, received patronage and support. Merchants began to return, and piracy and banditry abated as guards returned to roads and ports.   The long-awaited return of prosperity and peace for Scythia did not stop Maises from reflecting on his wartime experience. Secluded in Taurike, he began to draw up plans for a significant administrative overhaul of the Scythian army, basing it on a series of formalised obligations between land-owners and the crown to provide troops of a set number and quality based on the wealth of the land in question. After the success of the Gothic settlement, he also opened the door to further migrations of germanic tribes in Epirus and the surrounds, drawing from them to create a personal bodyguard based in Neapolis.   The world in the 25th year of Maises II (the Gallic blob is a Pelagian Gallic great conqueror warlord who has completely crushed the Gallic empire. Interestingly, he’s from the East - one of the few Gauls of the Boii tribe).

Yuiiut fucked around with this message at 05:42 on Sep 3, 2023 |

|

|

|

Clearly one of those time periods where just holding on is a success. Hopefully they'll continue to do so.

|

|

|

|

yeah boiii

|

|

|

|

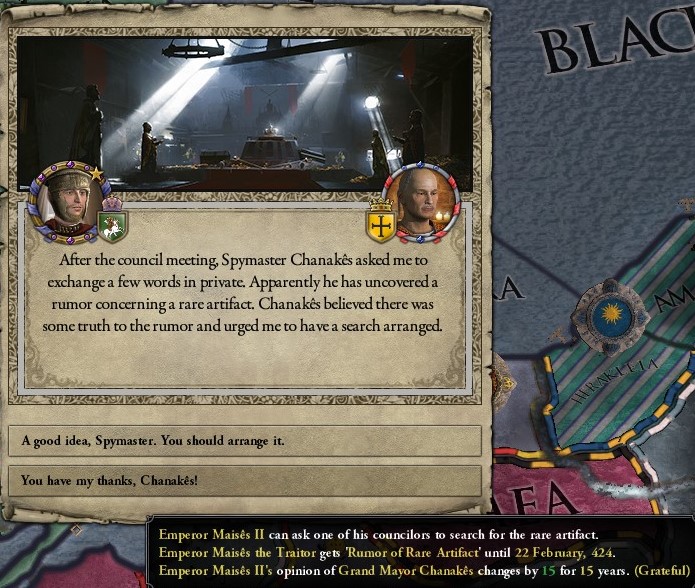

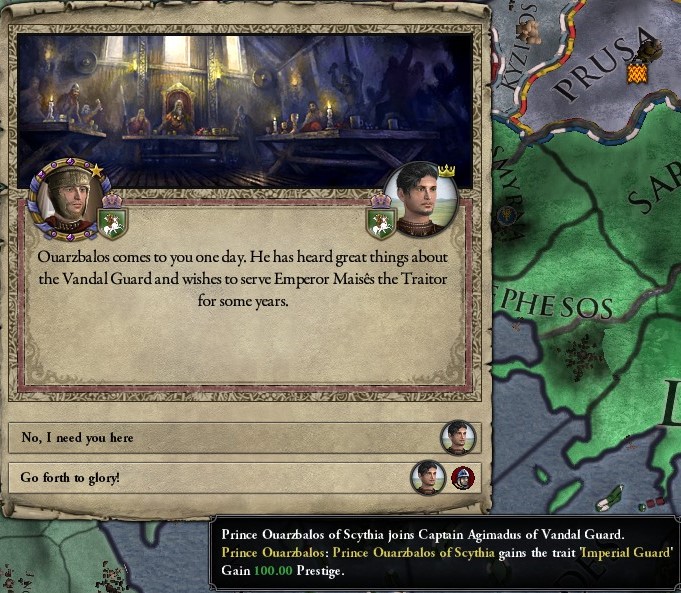

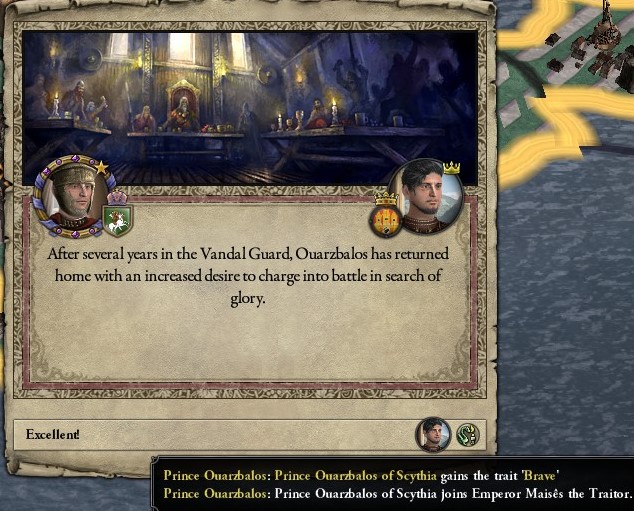

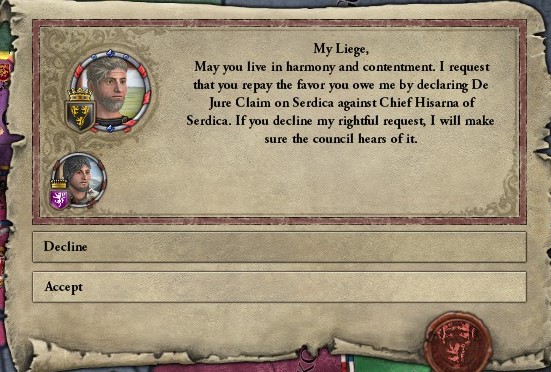

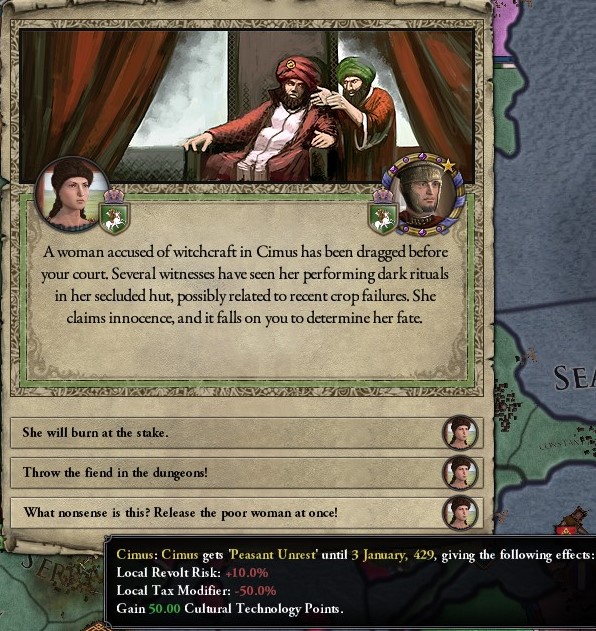

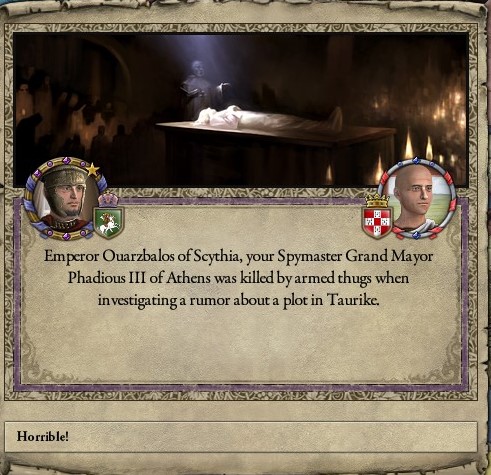

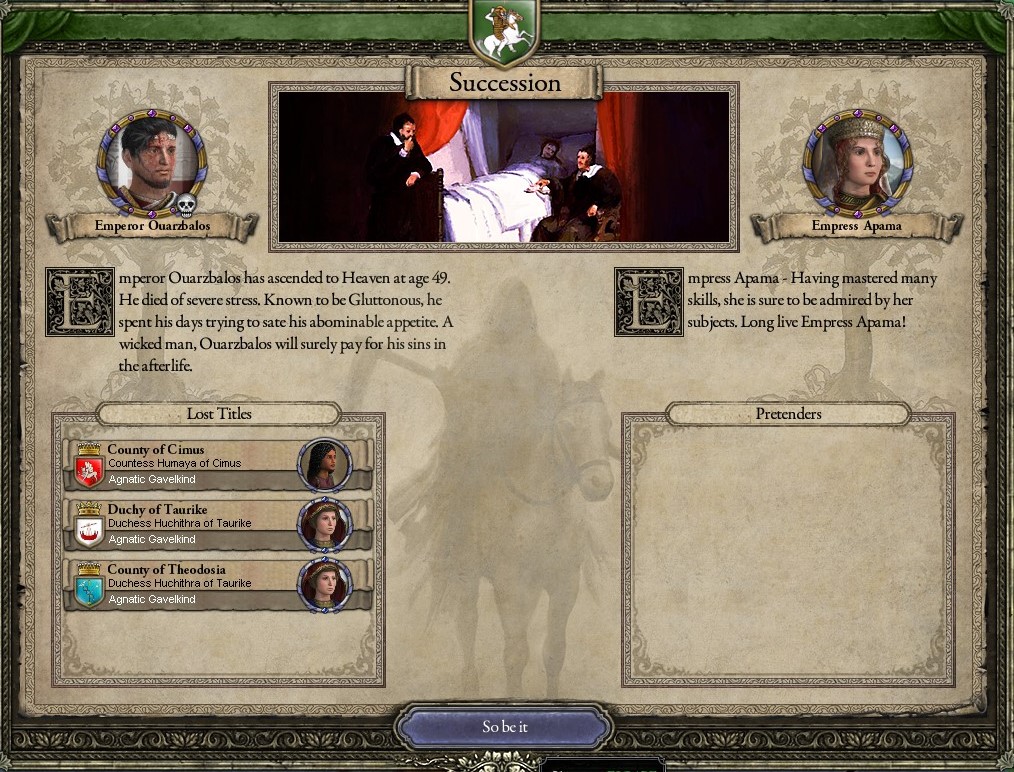

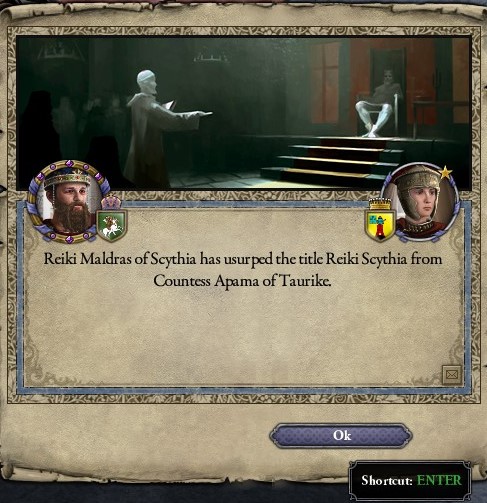

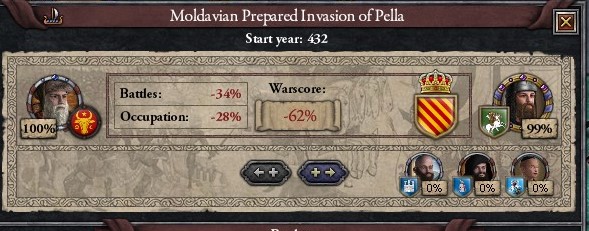

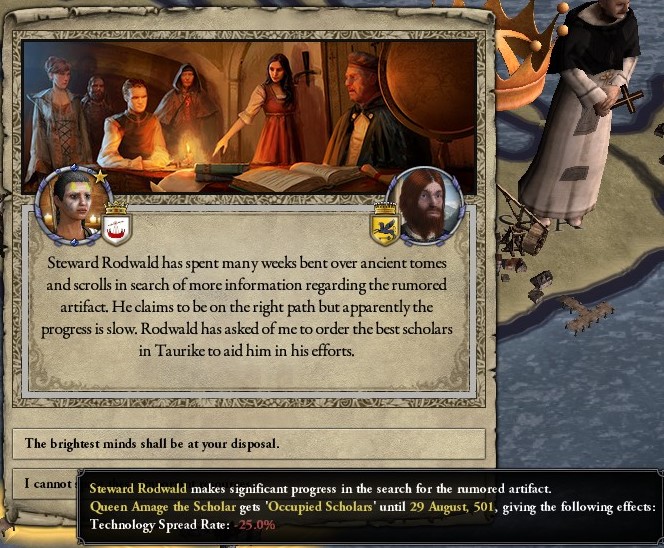

18: A chronology for the ages The turmoil and war which had marked the early reign of Maises II left him a staunch isolationist, unwilling to wage war outside the realm. While portions of Thrace remained in the hands of disparate groups of slavs, pirates, and petty kings, Maises was unwilling to commit force to their pacification or eradication, preferring to crush any raiders who trespassed against Scythian subjects while leaving their camps in peace. For the council, especially those with estates near the border, this was an unacceptable display of timidity and passivity in the face of rampant aggression. Matters came to a head in the 26th year of Maises’ reign, and he was provided with an ultimatum to see a rising Avar warlord on the illyrian frontier brought to heel or face open mutiny.  While Maises ultimately acquiesced, being unwilling to risk a civil war over his pacifism, we insisted that the army summonsed at Pella be held back 2 weeks after the omens for the war were initially deemed unfavourable. While the marcher lords on the council found further delay infuriating, they agreed to Maises’ delay, which had endeared him to the common soldiers and Vandal guard.  Maises wasn’t concerned with the opinion of the nobility or the common soldiery, however - the divination had troubled him deeply, and confirmed to him that the day of judgement could not be far away. What would material concerns matter, when the world itself would soon be unravelled, and the divine souls residing on it called to either ascend to further realms of light eternal or find themselves too entwined with the world to escape the destruction?  On the war’s success, Maises summoned the council, informing them that he sought to discover how long the world had existed, in order that its end could be better calculated. To that end, the resources of Scythia would be diverted to such purposes. Old libraries and tomes would be searched, ancient buildings inspected for indications - anything that may give a lead on the age of the world would be used. Even Christian and Jewish sources would be accepted, with rabbis and bishops summonsed to Neapolis to give their accounts.  Such demands were by no means popular, especially with the Christian and Jewish merchants, who refused to turn over manuscripts and codexes on Maises’ apparent whim. Offended by their obstinance and accusing them of being thralls to the Demiurge, Maises issued a series of decrees mandating the seizing of their property - not just books, but ships at harbour, property, and jewellery. While such laws were routinely violated across ports across Scythia, many merchants chose to give Scythian harbours a wide berth for several years as a result.  With Maises’ increasing millenarianism disconcerting the court his eldest son, Ouarzbalos, petitioned to be given command the Vandal Guard, taking a more prominent role at court and often sitting in his father’s seat to dispense judgement if Maises was indisposed or secluded in prayer. Ouarzbalos’ son, Maises, was often seen following his father around at such occasions, training and sparring with the Vandals with his father in the courtyard. Maises’ concern about the coming apocalypse notwithstanding, the Yarkarm family was thriving - and Scythia with it.  With the masses of information and books compiled as a result of the confiscations, Maises and his scribes discovered that there was not enough evidence in Scythia for the world’s age. If they wished to predict Judgement Day with any certainty, they would need relics and books from cities older than could be found in Scythia. While the Egyptian cities on the Nile were the oldest known in history, they were in no position to be ransacked under the Lechian pharaohs. Babylon, however, was stricken by war and known to be nearly as old, besides being the birthplace of the prophet Main. So Scythian troops were dispatched - to serve as mercenaries for either the Babylonian kingdom or the slavic invaders as they saw fit, and to bring home artefacts which could indicate the true age of the world.  Ouarzbalos himself was dispatched with the mercenaries to oversee their pillage and ensure that any truly extraordinary finds made their way back to Maises. Left unsaid by him as a he departed, but well-understood by Maises’ courtiers was the fact that it also served as a chance to have him exposed to battle and command - experience which he was unlikely to develop in Scythia. Serving under the slavic chiefdom, he proved himself to be quite valiant in battle, even if his actual command skills proved amateur.  The crowning triumph of Ouarzbalos’ return was not his personal feats or the course of the war itself, but the shipping to court of an ancient tablet, discovered in the excavation of fortifications for a siege camp outside Babylon. While translating the runes proved somewhat difficult, the language resembled Scythian in some regards, and it was soon discovered that it was an edict of Cyrus the Great, set down shortly after his conquest of Babylon. Most notably for Maises, Cyrus’ restoration of Babylonian temples aligned with the arguments put forth in the scripture he had seized from Jewish merchants, meaning they could be used to calculate creation’s date by working backwards.  While Ouarzbalos was pleased to see his father so happy, he knew the tolerance of the court for further expenditure was stretched extremely thin. Conniving with Maises’ council, they presented a proposal to him - to avoid distractions from his studies and writings, the court at large would decamp for Thrake for the season, and suppress some of the more violent slavic tribes which had settled in the region. Ouarzbalos would gain more experience in command, the court would see Scythia’s enemies pushed back, and Maises would be spared the distractions and irritations which came from the court.  Maises was only too happy to agree, and spent the season pouring over manuscripts and tallying ages of the judaic patriarchs. When the court returned after the war, he was proud to present his discovery - the world was some four and half thousand years old, according to his work. While this was a distressingly long time that the Demiurge had been in control of his creation, this could only mean that the destruction of the world and liberation of entrapped souls was soon at hand - hence why Mani had come to bring the truth to the world, that all may have a chance at being saved.  While the court had found Maises’ pre-occupation to be somewhat irritating, they were as a rule genuinely impressed with his devotion and piety, and in no position to question his estimates of the world’s age. However, there was a more notable concern - the Sarmatians, overthrown in the course of the Yarkarmii restoration, had never accepted the creed of Mani and held to the practices of Old Scythia - allegedly, even to the extent of practising human sacrifices. With the end of the world apparently so close, could such depravity see all of Scythia dragged down? Or would the violence that would have to be meted out against them to put a stop to their ways a worse sin? Or was this all a ploy by Maises to see his enemies cast down? The council was divided down the middle, unable to decide how to approach the Sarmatian matter.  What finally swung Maises into action was a report that the Sarmatians were not merely practising heathen ways on their own, but allegedly enticing other Scythian subjects - Christians, Jews, and even Manicheans - to join their rites. While a certain degree of realism and pragmatism had enforced some level of tolerance in the realm, the prospect of souls being lost was one which couldn’t be tolerated. The Sarmatian chief, Sturanos, was summoned to appear before the council in Pella, but Maises didn’t even wait for the predictable refusal before marshalling his own troops and family - Ouarzbalos (and his son Maises) would finally get to accompany his father in the warcamp.  Landing in Korinth, Maises was horrified to see the Vandal Guard expect the pillage and loot the place, chastising them for the avarice and lack of devotion. While this nearly sparked a mutiny, Ouarzbalos and Maises Junior were able to calm the warriors by promising loot from the Sarmatian warcamp, not their holdings themselves. Maises Junior - the future Maises III - seemed to have picked up more than his father regarding the art of command, and was entrusted with a delegation of Vandal and Taurician troops to cross the Peloponnese and lay siege to a Sarmatian fortress blocking further movement.  While the fortress fell with speed - Maises having employed locals to make a show of digging tunnels to start sapping the fortress walls, before leading a squadron of Vandals over the walls under the cover of night from the other side - the cost proved greater than could have been anticipated as a outbreak of camp fever ripped through the camp. Even as Sturanos and his ragtag followers were hunted down by Maises II and Ouarzbalos, Maises Junior died in the fortress, six days after capturing it.  As tragic as the death was for Maises and Ouarzbalos, it was more concerning still for the rest of the realm. Maises was Ouarzbalos’ only son, with three sisters. The rules of the Republic had been clear that no women would be entitled to rule, but the Republic was long dead. Would a woman be permitted to sit on the throne? Could a woman lead men into battle? What of Maises II’s second son? Would he inherit from his brother. As the Sarmatians were led away in chains, and Maises’ body born back to Neapolis to be buried in the Yudkaeveon (which Maises ordered the expansion of and the construction of a ever-burning brazier in), Maises and Ouarzbalos sought privacy in the ship’s cabin, where they could be seen talking in low voices..   not everyone who followed Maises’ lead was welcomed By the time they made it to Neapolis, a decision had been reached. Maises II, by then 64 and visibly frail, read out a short, simple announcement. Women were entitled to inherit if there was no man, and a man’s daughter could inherit his property in her own right if she had no brothers. After all, with the end of the world fast approaching, the duty of a ruler was to prepare their subjects for final judgement, no wage war and seek to conquer. Similarly, eunuchs (whether self-made or otherwise) were allowed to hold property and offices, although they were required to have a master if they were to hold any lands.  One year later, Maises II - the only Archon of Scythia to inherit the title and keep it - passed away quietly in his sleep. It was hardly unexpected, and as Ouarzbalos had been ruling as regent for a matter of months, the transition of power took place in a smooth, orderly fashion. The coronation took place down in Pella, and Ouarzbalos’ announced intention to review the administration and laws of Scythia, with intent to codify them and make them public, much welcomed - Maises’ rulings, while respected, had lent themselves towards obscurity and confusion, being developed out of scripture and religious reflection than tradition and pragmatism.  Of course, before he could really begin to rule, there was the Vandal Guard to deal with and whose loyalty he needed to secure. He remembered his time in the Guard with fondness and affection, and was more than happy to secure them an outpost in Tauricia, for them to see to training new recruits and cracking down on the same sort of pirates who had been the death of his grandfather, a perennial family problem his father, may his soul be in light eternal, hadn’t really devoted attention to.  And then there were the witch hunts - now that was something where him and dad had been on the same page! Of course, old Maises had been bothered by them because witches and diviners could help him ‘save the souls’ of the population and ‘bring the light of the Light to the darkness’ whereas he found that the people accused of being witches tended to also be people who knew where bodies were buried, what the old traditions of the place said about the law, and who in the village was cheating their taxes, but they had both agreed that witch hunts needed to be put down, even if it did upset the peasants.  And then there were the darker rumours - Phadious had been on to something he wasn’t ready to tell Ouarzbalos yet, except to keep an eye out and a dagger under the pillow, which wasn’t a good sign - and now he was dead, and no codifying the law was needed to call a spade a spade and a murder a murder. And the grand code was no closer to being done even though he’d been ruling for 5 years and now he couldn’t sleep at night and was having to have his food tested before he ate it so it always cold and he wondered if this is what dad had put up with all the time no wonder he turned to religion.  And then there were the slavs trying to invade Hellas again and at least this reminded him of back when he was young in Babylon and he could ride out against them because it was nicer to deal with someone trying to stab you from the front. Except the line collapsed and the Vandals ran and some giant of a man nearly cut his leg clean off before he broke free and fled and fled and just kept riding till he found a hut which he could crawl into just to rest for a little while.  And then there was nothing.  Archon Apama came to rulership unexpectedly, her father dying from his wounds and stress after the Scythian army was routed attempting to relieve Thebes from a slavic horde. The first woman to ascend the throne, her credentials as a ruler were under attack from the beginning - she had been trained as a courtier and diplomat, only receiving some instruction on war and administration as an adult after her brother’s death fighting the Sarmatians. To quell the murmuring of her council, Apama announced her intention to ride out - first against the peasants in Cimus, who had risen up after her father hung one of them for attempting to conduct a witch hunt.  Next, there was the matter of the Slavic migration - Thebes was still under siege and in desperate need of relief. With no time to marshal a full army, Apama sailed out of Neapolis with a small force of Vandals in the hope more troops could be marshalled in the mainland. Landing in Pella, an army of approximately 2000 was hurriedly gathered and marched south. While some 5 miles out of Thebes, they were ambushed on the road and forced to make a desperate break through the enemy lines to reach Thebes itself. It was there, outside the gates, that Apama discovered she was too late - Thebes had fallen and was garrisoned by slavic tribesmen, and the Scythian army was completely surrounded.   Having bartered all of Hellas for her freedom, it came as little surprise to Apama that the Scythian nobility considered her a complete traitor. What she thought of herself is unknown, but the great accomplishment of her father, grandfather, and great grandfather was undone in a single stroke. While the council plotted against her, it was the Vandal Guard who moved first, banishing her to Taurike with her sisters ‘as an act of mercy for your father’ and installing one of their own on the throne. In a final twist of the knife, her ship was raided by slavic pirates en route back to Scythia, and she was transported back to a reeking hall to be held for ransom.  Scythia itself fared little better - smelling blood, the sharks all swirled in to take a bite.   Six years after Apama’s overthrow, Scythia had ceased to exist.  The post-Scythian world So, I’m currently a broke count and have been sitting inside a raider’s dungeon for 4 years slowly trying to save up my ransom. As we’re in a regency, I’ll be turning to you for advice - how should we handle the destruction of Scythia? Option A: We can rebuild him Scythia is our family's birthright, our creation, our entitlement. We can’t let some jumped up Vandal vandalise our hard work and effort, and hopefully building it back piece by piece will allow us to build a powerbase strong enough to avoid a second collapse We will attempt to reforge Scythia, expanding within the de-jure bounds of Scythia. We will attempt to maintain our independence at all costs Option B: A poisoned legacy There’s a reason only our grandfather died peacefully - Scythia has chewed up generation after generation of our family and left us with nothing to show for it. We should take on smaller challenges, focusing on building up the Taurician peninsular and potentially seeking protection from stronger powers. We will try to consolidate Tauricia and expand slowly, if at all, outside the peninsular. We may seek vassalage under a strong power - potentially the Iazygians

|

|

|

|

B

|

|

|

|

B

|

|

|

|

lmao rip A

|

|

|

|

B Let the past die.

|

|

|

|

A. The past's death is a prolonged affair.

|

|

|

|

B

|

|

|

|

A

|

|

|

|

B

|

|

|

|

A

|

|

|

|

B

|

|

|

|

B

|

|

|

|

A Thread title

|

|

|

|

A

|

|

|

|

Well, the no's narrowly have it. On the plus side, we're not the only ones to lose an empire and storm off to sulk in a peninsular

|

|

|

|

Well at least we're in good company

|

|

|

|

19: Thicker than water Time. The greatest loss for Apama, kept in polite (insofar as a bunch of savages squatting in the ruins of an ancient Scythian manorhouse knew politeness, or etiquette at all) restraint by her captors was time. She knew that the money they had been promised from Pella for keeping her captive had never arrived. Who even knew who reigned down there, pretending to rule her grandfather’s realm when their authority barely extended to Pella’s gates? Certainly not her captors, ignorant as they were. When they’d turned to her, asking what her sisters and husband might pay for her return, she’d had to write the letter asking for her ransom herself - none of them knew their letters, and only a handful could speak Scythian, slowly and heavily accented.  They were not as cruel to her as they could have been, she supposed - she was tolerated on occasion at the feasting table, eating and drinking being the twin loves of her jailor Gradimir. Yes, an occasional warrior would yell something at her she barely understood when deep in his cups, but Gradimir had made it clear she was not to be touched, and fear kept his followers in line. Nonetheless, she was kept away from the boats and horses, and as months turned into years she waited for hope of ransom. Her eldest daughter would be an adult now, a woman in her own right - even if her sisters had turned against her surely her children would be moved to filial pity by her letters, willing to part with some treasure to free their mother from chains?  The view from Taurike and Neapolis was quite different from Apama’s view from her cell. The letters arrived, suggesting or demanding or pleading for silver or gold, weapons or trinkets - demands which would have been trivial two decades ago, when Neapolis perched on the mountainside above bustling docks and her streets thronged with merchants. In the hollow shell that remained, however, no such wealth could be found - it had been melted down and used to purchase mercenaries, whether by the state itself or the wealthy. Or it had fled the city under the cover of night, down the mountainside to secret docks where silent ships bound to Aegypt and Carthage and Talia were laying. Or it had been buried by an owner who never returned, lying under the earth as a testament to a future archeologist to know that once there was in this place wealth and power which envied none other on earth. Born and raised in the lap of luxury, Apama never came to understand fully what had befallen not just her family but her society and her kingdom. To her, the endless delay and the response - when it finally arrived - being her sisters questioning the suggested ransom and offering half what had been demanded, as if her freedom was an apple in the market to be haggled over, was proof that all involved were plotting against her. On her return, however, she discovered the truth - her sisters and daughters were not plotting against her, but her son.  In her long absence, her sisters and her daughters had come to resent Sauaiosos, her eldest son and heir, who had taken strongly after his father (a horse-prince of modest fame). Huchithra, the elder of her two younger siblings, had taken to ruling Taurike in Apama’s absence, and openly schemed against Sauaiosos from her court in the middle of the peninsular, while her youngest sister Humaya ruled the garrison-fort at the marshy gateway to Taurike from the open steppe beyond. In both their eyes, her son was a foreign prince who, as a man, may be championed by the non-manichean population as an alternative to their own rule.  While Apama’s return settled matters in her own family, with her daughters apologising for siding with their aunts over their brother, things could not be as easily smoothed over with Apama’s sisters, with relations souring between them when Apama accused them of leaving her to rot with the pirates while they set to plundering her birthright. Huchithra’s reply - that she had preserved the Yarkamii legacy which Apama had nearly destroyed during her disastrous reign at the helm of Scythia - put the stop to any hope the Sauaiosos could be left in peace, and after a disastrous assassination attempt (foiled when the would-be murderers spooked a flock of sheep in the hills, leading to their rapid discovery before they even arrived at the city walls), Apama had Sauaiosos removed from court and cloistered in a monastery high in the mountains, his location known only by him, Apama, and the monks.   Apama was left at court with her daughters - who, despite their repeated shows of repentance, she treated with thinly veiled disgust and disdain for their role in the murder plots - her husband, and her youngest son, a bright boy by the name of Phandarazos. The only member of the family young enough to have not been involved in the intrigues around his brother or the delay in her ransoming, she doted on him as the only child she got to see grow up, reminding him at every opportunity what her sisters had stolen from her, how her daughters had neglected her as she languished in chains, and how close his brother had come to death at the hands of assassins. Wrapped up in her own victimhood, she barely saw his disdain for her - for her weakness, her inability to stop her sisters, but most of all for her having held all Scythia in her grasp only to let it crumble - grow by the day, even as he promised that all the evils done to his family would be avenged.  In a different context - had he not been a second son but an heir in his own right, or happy to merely serve his family - Phandarazos’ skills may have proved invaluable assets. He had been old enough when the assassins had been captured to attend their executions, and unknown to the rest of the court he had been old enough to have eavesdropped their tortures. As he had heard them be scourged and confess their plans, he had learnt much, and in Apama’s court - filled with enmity, secrets, and bitterness, he had learnt more still. How to convince someone you were on their side, only to pass their secrets on without them ever discovering. Which words, whispered in someone’s ear, may convince them that a friend is an enemy or an enemy a friend. Appearing innocent when calamity befall an enemy, and making the most of true strokes of luck. Most of all, though, the damage and danger that even the rumour of a murder plot could do, tipping the court upside down as panic spread.  There is no conclusive proof that Phandarazos killed his mother. His sisters certainly never accused him of anything, and Apama’s fall off a balcony bore all the hallmarks of a true accident - the old buildings of Neapolis were notoriously dangerous, prone to collapsing or giving way suddenly. Even if it had been a murder, Apama, the self-styled last princess of old Scythia, certainly had generated many enemies and few friends in her lifetime. Yet the timing, coming when Phandarazos was a mere 17 years of age, has always raised eyebrows and suspicions. Maybe if Phandarazos knew where his brother was sequestered, Sauaiosos would have had an accident first, and Phandarazos’ life would not have ended in bitter exile. Some questions can never be answered though - when Sauaiosos heard of his mother’s death (some 3 weeks after the fact), he rode down the mountain and was welcomed as the new lord of Taurike.  Sauaiosos’ life at the monastery had given him a modest grasp of numbers and letters and an interest in Hellenic texts, but he was no mighty ruler. The greatest change induced by his seclusion was him escaping the endless family intrigues rapidly turning Taurike into a nest of vipers. In Neapolis, many ‘informants’ of Apama - who were, in truth, little more than jumped-up thieves and rumourmongers willing to tell the late ‘princess’ whatever they thought she wanted to hear - suddenly found themselves without pay and support, and their previously overlooked larceny and extortion suddenly subject to swift penalties.  It was all very well and good for Sauaiosos to try to put an end to the Yarkarmii infighting, but there was little he could hope to accomplish on his own volition. His aunts, by now powerful and secure in their positions, both held significant sway in Taurike, and it was only by winning them over that lasting change could be hoped to be created. And so Sauaiosos had set to writing letters and sending emissaries and gifts to them both before he had even left the monastery, recognising their landholdings, promising he had no claim on their titles, and recognizing Huchithra’s seniority over the Taurikian peninsular.  Initially, little headway was made - both of his aunts continuing to view his intentions with skepticism and concern, worried that his outward friendliness was merely a thin veneer over inherited bitterness and anger. Humaya, from Fort Cimus, decided to put his claim to the test. At 35, she was unmarried and had no legitimate heir (although she did have a bastard son widely rumoured to be a soldier’s spawn). If Sauaiosos truly wished to unite the family, he could marry her. If he refused, he proved to both his aunts that his words were empty flattery, and that their attempted murder of him had been the wise and prudent course of action.  While there were no restrictions on such a marriage in Manichean practice, it was an uncommon union - uncles marrying their nieces was reasonably common, but a nephew marrying his aunt was an almost unheard of rarity. However, for Sauaiosos, there was no choice - his aunts needed appeasement, and the family needed unification. And so, at age 20, he agreed to Humaya’s offer, and the two were married in the Yudkaveon with his aunt Huchithra and brother Phandarazos in attendance. The Yarkamii family was at last at peace with itself, and the marriage even proved unexpectedly fruitful - at the age of 40, Humaya fell pregnant, and gave birth to a baby girl. .jpg) The girl was greeted with absolute delight by her parents. After the wedding, Sauaiosos had accepted a role as Huchithra’s diplomat - smoothing things over with merchants and negotiating grazing rights for travelling horsemen from the steppe, a role his negotiations with his own family had set him up well for. In truth, he had never expected a child from his marriage - Humaya had been 15 years older than him when they married, and every year the possibility had seemed further and further out of reach. The girl was named Amage, after a famous queen from the distant past , and a grand feast organised to celebrate the birth.  The feast took some time to arrange - both Humaya and Sauaiosos had obligations in their own realms, and Humaya needed time to recover and recuperate. When it came, however, it was the event of the decade - even the somewhat reclusive Phandarazos was lured into attending, and Sauaiosos led the assembled nobility in a grand toast to his newborn daughter.  That would be the last thing he ever did.  The years were long during Amage’s regency. Her uncle Phandarazos initially ruled in her stead as regent, but after her mother died when she was seven (struck by illness after a meal, she wasted away slowly over two weeks), he claimed Cimus as his own, abandoning his niece in Neapolis to the tutelage of the local warriors and monks. While her education was limited in such circumstances, her abandonment taught her early that while plot and schemes could do much, power at spearpoint was far more difficult to challenge. Outside her immediate circle Neapolis fell back into the hands of thieves and brigands, and the roads of the realm grew unsafe as the child slowly came of age.   As she came of age and began to lead men against such brigands, re-opening the roads and the coasts to travellers and traders, she began to develop a modest reputation as a leader of men, attracting the attention of her elderly great-aunt, who charged her with leading Taurike’s soldiers on patrols to defend the border while still a teenager. In short time, Amage showed competence and promise against slavic and germanic pirates, and soon developed a name for herself a protector of Taurike’s borders and formidable duellist in her own right.  Such a reputation attracted many admirers and flatterers, and it was not long before Amage had courtiers pointedly noting that, as the only legitimate child of Humaya, she had much more of a claim to Cimus than her uncle, who had unjustly seized it in her minority. Such murmurings were, of course, only intended as empty flattery by those who said them, all nobles long used to the intrigues and rivalries of Yarkamii courts, and expecting little to come about as a result of them. Amage had lacked such intrigue or upbringing in her deprived youth, and instead took the remarks quite seriously, marshalling an army and invading her uncles land before her stunned courtiers had a chance to react.  When the news reached Huchithra that her great-niece had marshalled banners and marched against her nephew, Agame’s uncle, she was taken aback and fell quite faint - the family had fought before, but not to the point of open war. A strong missive was sent to Neapolis instructing Amage to disband her forces and explain herself, but by the time the boat reached the city Amage and her army were outside her uncle’s walls, preparing to storm the fort. The outraged missive from Huchithra arrived at the fort 4 days after it’s fall, and an offended Agame took it as a declaration Huchithra had declared for Phandarazos.  In truth, Huchithra’s message had outlived its sender, who had never recovered from the shock and who had passed away three days prior. Her son, Argoun, had taken over the rule of Taurike in her stead, but the few men willing to swear for him swiftly melted away as Amage’s host wheeled east, and in a matter of weeks Argoun had joined Phandarazos in exile as Amage was hailed as the liege of all Taurike.   Amage’s realm at 35 Yuiiut fucked around with this message at 01:01 on Nov 16, 2023 |

|

|

|

Looks like you're calling Amage "Apama" in the latter parts of the post.

|

|

|

|

It's always nice when the event that makes your heir ambitious but your rival actually has consequences.

|

|

|

|

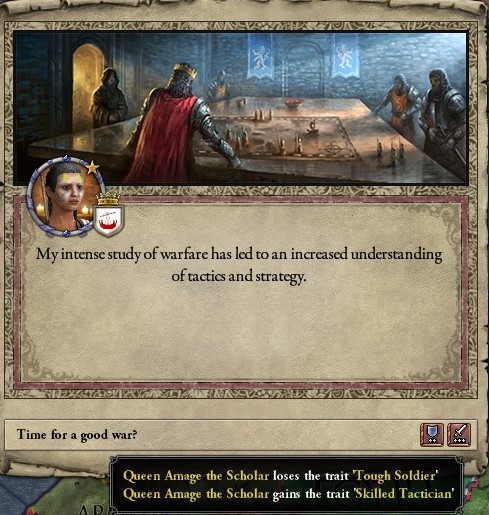

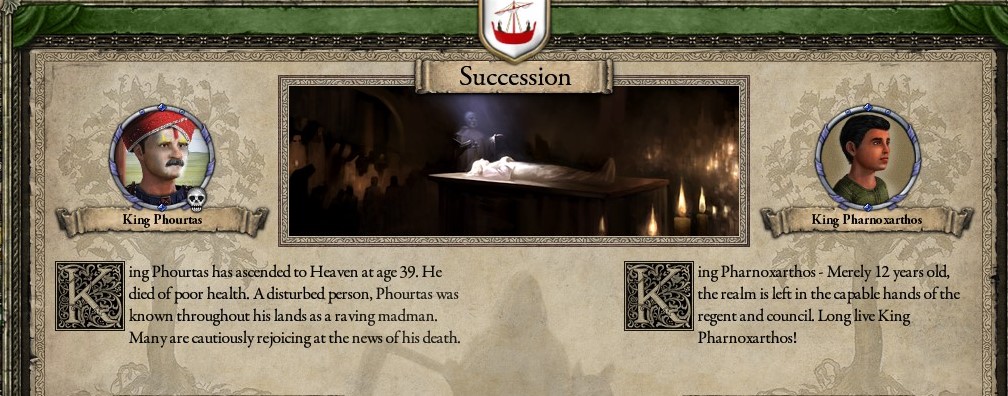

20: Gnosis With her immediate family dead, exiled, or reduced to dependency, Amage turned her attention to higher affairs. The Taurikian court was a shadow of what had once existed - the Scythian court records held in Neapolis referred to positions like ‘commander of the navy’ and the realm’s ‘chief scribe’ which had long gone extinct. The only trace of the Scythian administration was the continued presence of eunuchs in the administration, and even they had dwindled, becoming rarer and more expensive than their forebears had been. Determined to reverse the decline and retain some share in past glory, Amage began sponsoring libraries and scribal schools across Taurike, inviting intellectuals and importing books from many distant ports.  One of the most prominent arrivals into Taurike was a large contingent of monks and nuns from Western Carthage, who followed the increasingly popular school of Valentinus. A priest-scholar active in Alexandria some 300 years prior, Valentinus’ followers tended to found secluded communes segregated by sex, where they would work, pray, and study and copy texts relating to their beliefs and cosmology. While their beliefs were not entirely compatible with Scythian Manicheanism - the Manichean elect preached of a world composed of darkness and light in equal measures, and the ‘Valentinians’ preached instead of a irredeemably fallen world which must come to an end through Christ - their proselytising and tendency to found communes in rural areas which rarely heard from the more urbanised Manicheans saw them winning over large numbers of peasants to their cause.  The Valentinians were most active, and most encouraged, in the eastern most parts of Taurike, where they sought and gained the patronage of Amage’s most important supporter, Rodwald. A furiously intelligent man, he was the descendant of the long defunct Vandal Guard, although thoroughly Scythian in his speech and mannerisms. Amage had put him in charge of the realm’s finances as well as requesting his support for her campaign to encourage learning, and on both fronts he had been doing a highly effective job.  When he approached her, indicating that the Valentinians had been seen demanding that they be supplied with copies of all the books held in the libraries of the Manichean elect for their own research and understanding, he indicated that doing so would doubtless harm the realm in the short term, but would like bring significant benefit in the long run. The Valentinian scribes were the best in the realm in their work, and allowing them to produce copies of texts and check references and citations was sure to lead to many theological advances. Amage agreed, and gave him carte blanche to provide the followers of Valentinus with ‘whatever manner of assistance they may request’.  This sponsorship and tolerance ended up paying off significantly. In 503, the Slavic warlord of Phoenicia started violently suppressing the Valentinian communes in his land, causing many to flee to safer lands. While many fled westward across the sea, several communities from the lands around Yerushalem instead fled northward to Taurike, to settle amongst their brethren there. One such group carried with them various trinkets and artefacts salvaged from the Second Temple, including a small ring which was said to predate the Second and First Temples itself - the Ring of Solomon. Offering it for safe passage and the right to settle in Theodosia, it was given over to Amage.  While libraries and the court were revitalised under Amage, Neapolis itself saw revitalisation and expansion. The wooden fortification at the centre of the town, built over an old Scythian wall, was torn down and the wall itself rebuilt and strengthened in stone. Rodwald was put to work finding the funds for such projects, and was able to levy an additional tax on merchants arriving along the Silk Road from the east, an increasingly common sight at the Taurikian ports.   As Amage aged, the Manichean elect, disgruntled by the tolerance shown to Valentinianist preachers and communes, began to lobby for increased privileges and support to be given to them. Unwilling to suppress the Valentinians, Amage instead turned her attention to the north. The lands between the Borysthenes and Taurike proper - once the site of great estates during old Scythia’s height - were now inhabited by a variety of Magyar tribes who supported themselves hunting and fishing along the riverbank, with a minor fur trade supporting the warrior elites luxuries. Nominally owing fealty to the Bolghar khan up the Rahā valley, they were of little import and attention in his plans. When one of their traders visiting Neapolis got into a drunken argument with a Manichean functionary, Amage seized the opportunity to proclaim that the ‘offences to the Manichean faithful’ caused by their heathonry could no longer be tolerated, and marshalled her forces for a punitive expedition.  The war ended up being a reasonably short affair - Amage burned her way along the southern riverbank, scattering the Magyar tribesmen in her wake and constructing a string of forts to secure her conquests. A cursory force sent by the Bulghars managed to bypass the forts in a bold strike southward, but proved incapable of scaling the walls of Neapolis. Trapped and running low on food and supplies, they ended up being caught by Amage’s army on her return and annihilated shortly outside the city walls, with the Bulghar nobles captured offering peace for their freedom.  Returning home to Neapolis, Amage sought out an account of Alexander the Great’s own conquest, seeking to apply her newfound knowledge to the lessons found in the ancient histories. The libraries were more than happy to supply the ancient Hellenic accounts, and Amage found much of value in studying the great general’s logistics - her unwillingness to advance past the river into the steppe compared to the Bulghar’s mad dash to her capital outrunning their supply lines proved to her that while she could advance along the river in relative safety, taking her army out on the wide steppe itself would be risking complete annihilation by either the enemy or starvation.  While Amage’s skill as a leader and warrior continued to grow, her attention to her family had long been cursory at best. Her eldest, Pharnoxarthos, was a kind soul who burnt with desire to take command and rule in his own right. Such noble motives were, unfortunately, the sole redeeming qualities he possessed - in public he proved a shy, stammering figure, prone to making the women of the court uncomfortable with open leering and utterly uninspiring. More concerningly to his mother, he had proved stubbornly illiterate, unable to read the simplest text without heavy coaching. To encourage his skills, he was given command over the new acquisitions along the Borysthenesian riverbank, and encouraged to grow his own authority.  While dispatching her son to the north, Amage was approached by a scribe who excitedly announced that they had located - buried in an ancient copy of the Hermetica - the burial place of Hermes Trismegistus himself. Departing immediately for Alexandria to search for it, Amage installed her husband Karsas in command of Taurike proper, instructing him to act as regent in her stead. Arriving in Alexandria, she was immediately struck by the roiling heat baking the ancient city, and progress along the towards the tomb’s alleged location proved slow and torturous. When she arrived at the site, she was disappointed to find all the tombs apparently plundered and empty. It was only sheer luck which had one of her servants stumble and fall through a false wall which revealed the main burial chamber, containing within it a wealth of bejewelled items - most prominently, an ancient tablet embedded with lapis lazuli and gold. While the hieroglyphics proved impossible for them to translate on the spot, Amage felt confident she had discovered the burial place of Hermes himself, and that once translated, the tablet would prove the key to perfecting the science of alchemy.  Sadly, when she returned with her find to Neapolis, she arrived to a city in mourning - Karsas, her husband, had passed away in her absence, and her arrival to the city was 2 weeks after his funeral, so she didn’t even get the chance to see the body. Despondent and depressed, she took to forsaking the court, spending long periods by Karsas’ grave or buried in the library, furiously trying to make sense of the accursed tablet. In the end, she found it futile, proclaiming the matter was beyond her skill as a scholar and bemoaning that the affair had proved to be nothing more than a folly, wasting away her time and attention as her husband died.  If Amage had taken her husband’s death poorly, her children took it in an even worse fashion - Amage, cold and distant, had never been the best parent when she had even been around, and Karsas had been their guardian while growing up. Pharnoxarthos, already melancholy from his dismal failure to govern the northern Magyars in anything resembling his oversized ambitions, took it the worst. Messengers from his lands indicated that he had taken to locking himself inside his hall and refusing company and food, and it came as little surprise when he followed his father into the grave a mere three months later, dying of a cold which the rest of his court had shaken off with ease. His son, Phourtas, was announced as his successor and the heir to Taurike, although Amage barely even appeared at the court for his presentation.  Even as Amage recovered from her grief, she found that her body was beginning to fail, and where she could once ride through the city and wear a mail coat she now found herself struggling to walk from her chambers to the court. More and more courtiers were turned away when they came to visit her, and those permitted in her chambers for an audience tended to visit only briefly, hurrying out with tight lips and wane expressions subsequently. Amage, the unquestioned queen of Taurike for 40 years, was clearly dying.  Finally, at 66, Amage breathed her last and her grandson Phourtas ascended the throne. While not quite as incompetent as his father, his noted lack of interest in his wife and large amount of time spent in the company of his male courtiers had given rise to a number of scandalous rumours about his children’s true parentage. While Phourtas was a reasonably hardworking king and willing to give others credit where appropriate, his open impiety and scorn for the elect - ‘a bunch of useless philosophers who want money for nothing’ did little to endear him to the learned courtiers his grandmother had sponsored, and he found Taurike to be ill-suited for him.  In part to get away from the capital, and to spend more time in male company, Phourtas declared a continuation of his grandmother’s campaign against the Bulghar vassals along the Borysthenes, marching his armies as far east as the outskirts of Tanais before wheeling to crush a Bulghar contingent marching from the north. The war was of little account, and Phourtas showed little interest in the spoils, charging his uncle with the management of the conquered lands before returning to Neapolis. When Phourtas returned to the capital he found his wife - unexpectedly - pregnant, despite his month-long absence. Suspicious of her faithfulness, he paid large sums of money to have her followed - a fact which swiftly made its way into the more scurrilous rumours already following his children.  And then, quite unexpectedly, he choked to death on a duck’s leg while holding court. This left his 12 year old ‘son’ to take the throne of Taurike under the wise tutelage of the local nobility, who would govern the realm and see to its defences while young Pharnoxarthos was raised in the ways of kingship.  In the long years of Amage’s reign, and as a result of the successful campaigns against the Bulghars, the nobility had grown somewhat complacent in Taurike’s defences, which had not been seriously challenged in decades. With Pharnoxarthos in his minority, this was set to change, and the Iazgians in the East swept across the straits of Azov, massacring the garrison and announcing themselves the new overlords of Taurike. Foolishly assuming that the Iazgian horsemen would be as easily swatted aside as the half-hearted efforts of the Bulghars to defend the Magyars had been, the regents rode out against them.  Cherco was a massacre - not only was the Iazgian army larger than the Taurikian one, but the saddles on their horses had dangling footstraps attached to them, giving their riders much more stability on the horse. While Scythian cavalry had long been formidable on the charge with a lance, a horseman surrounded by foot soldiers was often enveloped and knocked off his mount with relative ease. The Iazgians suffered no such impediment - with his feet secured in the stirrup danglers, a Iazgian horsemen wielding a sword could smite any soldier near his horse with perfect balance, posing a fatal threat to any Taurikian soldier trying to dismount him. As the few survivors from Chelmo hurried back to Neapolis, it was quickly agreed there that Taurike stood no chance - a surrender and acknowledgement of Iazgyian overlordship was the only path forward. State of the World Taurike and the environs In the North, we are under (a vassal khan of) the Kouzaiosid khanate. The Iazgians have been doing extraordinarily well - one branch has taken over the remnants of the old Parthian empire, others have pushed East and displaced the Huns. Generally, they follow old Scythian paganism and perform divination and animal sacrifice. To the north of Taurike proper, the Magyar tribes have settled and been subjugated by the Bolghars, and the slavs have mostly left for southern climes.    To the West, Carthage lives on in the city of Cadiz, which has become the capital of the Punic world - Carthage proper being occupied by German and Slavic tribes multiple times. They follow the path of Valentinus (we keep flipping back and forward on who the ‘heretics’ are in-game). To their East, there are the various successor kingdoms of Gaul - urbanised to some degree and based on feudal principles, they are the remnants of the realm of the great Orgetorix, who conquered Gaul some 150 years ago. His legacy lives on not only in his family (although all direct descendants of his have passed), but in his sponsoring of Pelagianism - all major Gallic kingdoms remain Pelagian to this day, and Gaul remains the most significant centre of Christianity in the world. Above Gaul proper are a smattering of islands - filled with bogs, mist, and druids, the tribes there pass the time cattle-raiding and are irrelevant.     In the centre of the world, there are innumerable numbers of slavic warlords and tribes moving across the shattered carcass of old empires. Babylon, Egypt, and Phoenicia have all passed away, although some of the more powerful warlords cloak themselves in names of old. The peasantry at large remains much the same, still tilling the same fields for new masters with new tongues.    Last of all, and most grand amongst the nations, there are the lands past the Ganges. For a traveller from the West, crossing the Ganges is stepping back in time. Here there has been no fall - the indianized Hellenes have lost their state, but have become part of the great legacy of Ashoka. Buddhism recieves the most state sponsorship, though some contributions are made out to vedic priests - both Jain and Hindu alike. A traveler can walk the length of the Ganges itself and stay in a single kingdom the entire route - an empire like none other in the world.

Yuiiut fucked around with this message at 23:44 on Dec 17, 2023 |

|

|

|

That is a great many runs of bad luck, alas.

|

|

|

|

Writing up the next chapter, but in the meantime have an article proving Herodotus' claims that Scythians would use their enemies flayed skin for leathercraft have at least some level of truth. It also has more images of Scythian goldwares - the Scythians were renowed amongst the nomadic tribes of their time for their jewelery, which has left them more of a material legacy for archeologists than their fellow nomads.Herodotus posted:A Scythian drinks the blood of the first man whom he has taken down. He carries the heads of all whom he has slain in the battle to his king; for if he brings a head, he receives a share of the booty taken, but not otherwise. He scalps the head by making a cut around it by the ears, then grasping the scalp and shaking the head off. Then he scrapes out the flesh with the rib of a steer, and kneads the skin with his hands, and having made it supple he keeps it for a hand towel, fastening it to the bridle of the horse which he himself rides, and taking pride in it; for he who has most scalps for hand towels is judged the best man. Many Scythians even make garments to wear out of these scalps, sewing them together like coats of skin. Many too take off the skin, nails and all, from their dead enemies’ right hands, and make coverings for their quivers; the human skin was, as it turned out, thick and shining, the brightest and whitest skin of all, one might say. Many flay the skin from the whole body, too, and carry it about on horseback stretched on a wooden frame.

|

|

|

|

what a beautiful mess

|

|

|

|

Welp

|

|

|

|