|

Its something that varies a bit based on the era, but essentially its a really, really gruelling series of exams on Confucianism that take an extreme amount of effort and time to do. You'd need to memorise multiple classic texts, and the pass rate was about 1%. You'd need to pass for a position in the government bureaucracy or as a proper scholar. In theory it was egalitarian as any man could do it, but language barriers and resources get in the way. Plus rich people could pay for academies or bribes. Its really handy for uniting an empire by ensuring the government has a shared philosophy, language, lived experience and writing style. For poetry it means there's a lot of educated writers who've looked into a lot of philosophy and the classics, and been through some extremely high pressure times from early childhood, and are part of and writing to a professional class of scholars. Wrestlepig fucked around with this message at 07:41 on May 24, 2023 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 9, 2024 08:32 |

|

Wrestlepig posted:Its something that varies a bit based on the era, but essentially its a really, really gruelling series of exams on Confucianism that take an extreme amount of effort and time to do. I'still reading Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom and while so much about the events around the Taiping Rebellion sound completely insane (and the vast majority of it not the LOL kind of insane), one of the most insane is that Hong Xiuquan sparked it all off after he had a mental breakdown from failing the exams multiple times and started having visions of Jesus saying Hong Xiuquan was his younger brother.

|

|

|

|

Great summary, and it really can't be emphasised enough how much impact exam-and-parallelism-related mental breakdown had on Chinese history. The imperial exams were key to China's coherence and continuity as a state. It was important that they were perceived as legitimate, which was helped along by roots reaching into hazy myth-history and really close ties to religion. There were multiple Daoist gods you might ask for a bit of luck on your exams, whether you were studying for the basic county level degree to become a 'recommended man' or travelling to the capital hoping for a first-class rank in the jinshi (where you'd attack contemporary political problems along with the usual tests of composition, calligraphy, knowledge of the Classics, etc). A theme among these ascended gods was having been wrongfully denied their degree because the emperor didn't find them pretty enough - something that shows that the people considered fairness important. There were genuine attempts at reducing corruption - various codes to identify yourself to the examiners were squashed, and in the Song dynasty they disguised the candidates' hands by having transcribers rewrite every paper. (Note the natural converse to schmoozing your way to success - you could be Liu Yong, who supposedly had his name crossed out by the emperor twice after passing thanks to indiscreet ci lyrics, or Li He, denied the jinshi because it sounded like his dad's name.) The scholar-officials who administered the imperial bureaucracy were chosen through the exam system, and actively hampered from building individual power bases. You weren't allowed to serve in the province you came from, for example. As a member of the one traditional social class that didn't produce obvious use-values (unlike farmers or craftsmen) or, theoretically, shift luxuries in pursuit of vulgar profits (unlike merchants) they were at the mercy of the state and expected to live its values even if it killed them. Which it might - the virtue of remonstrance meant you were supposed to criticise superiors who'd gone astray. With tight quotas in place for much of Chinese history, the system also produced a lot of lower ranking technocrats and extremely well-read artistic types who survived as itinerant composers, painters and the like, diffusing cultural mores more widely. Obviously there are poems about the exams: Yu Xuanji, tr. Leonard Ng posted:Visiting Lofty-Truth Monastery and Viewing the Names of New Graduates at the South Tower Li He, tr. JD Frodsham posted:To Be Shown to My Younger Brother Shogi fucked around with this message at 18:41 on May 24, 2023 |

|

|

|

good lord, this is the bleakest poo poo ever. Mei Yaochen, tr. Kenneth Rexroth posted:Sorrow

|

|

|

|

Insanite posted:good lord, this is the bleakest poo poo ever. that one's a brute. you get some rough moments reading through Mei's stuff that hit about the same way as Bai Juyi's Golden Bells poems. the orig is along these lines read in Mandarin: 天tiān(sky|heaven) 既jì(already) 丧sàng(lose|bereave|die) 我wǒ(my) 妻qī(wife) 又yòu(once again|also) 复fù(return|repeat|again) 丧sàng(lose|bereave|die) 我wǒ(my) 子zǐ(son) 两liǎng(two|both) 眼yǎn(eye|crux) 虽suī(although) 未wèi(not yet) 枯kū(dried up[implication of withering drought/dry season]) 片piàn(slice|incomplete[or with tone 1 this is a colloquialism for 'heart']) 心xīn(heart|mind) jiāng(shall) 欲yù(wish for|appetite) 死sǐ(die|impassable) 雨yǔ(rain) 落luò(fall|rest with) 入rù(go into|join) 地dì(earth) 中zhōng(within|middle) 珠zhū(pearl) 沉chén(sink|drop|deep) 入rù(go into|join) 海hǎi(sea) 底dǐ(end|bottom) 赴fù(go|visit) 海hǎi(sea) 可kě(able to) 见jiàn(see|meet) 珠zhū(pearl) 掘jué(dig) 地dì(earth) 可kě(able to) 见jiàn(see|meet) 水shuǐ(water) 唯wéi(only|alone) 人rén(man|people) 归guī(return|belong to) 泉quán(wellspring) 下xià(down|below) 万wàn(ten thousand|numberless) 古gǔ(ancient|ages) 知zhī(know) 已jǐ(already) 矣yǐ[a final particle that intensifies its clause] 拊fǔ(touch) 膺yīng(breast) 当dāng(when|should|exactly) 问wèn(ask) 谁shéi(who) 憔qiáo(haggard) 悴cuì(sad - 憔悴 = 'pale and thin', or 'withered' re: plants) 鉴jiàn(reflection|mirror) 中zhōng(within|middle) 鬼guǐ(ghost|demon) lots of the couplets have exact repeats or assonance & parallels between each line in characters 3 and 4, which adds to the feeling of inevitability and the loss happening again and again. there is this theme of water, and Mei's eyes always being productive (tears, his sadness inspiring poems etc) but his body withering like crops in a drought. the last line you can read as Mei having no one left to turn to, or him not even recognising himself anymore (the ghost/demon within the mirror). it's really excellently crafted

|

|

|

|

NGL, it is surprising to feel wrecked by thousand-year-old poetry.

|

|

|

|

That one is super bleak for sure. The Underground Springs reminds me of that one Tennyson line, "Fresh as the first beam glittering on a sail, That brings our friends up from the underworld," This thing that can never happen, that you can't really feel except in a dream and then when you wake up, you end up feeling betrayed somehow when you remember reality and the finality of time. Something less bleak from Meng Chiao, since we were talking about the exams: After Passing the Examination The wretchedness of my former years I have no need to brag: Today's gaiety has freed my mind to wander without bounds. Lighthearted in the spring breeze, my horse's hoofs run fast; In a single day I have seen all the flowers of Ch'ang-an. This is the same guy who gave us Laments of the Gorges, so it's pretty amazing to me the range the classic poets demonstrate. This one in particular I remember personally reading after finishing my undergraduate finals and the feeling of carefree strolling through the city seeing everything beautiful beamed into my heart from the 8th century.

|

|

|

|

I read The Good Earth translated to English and formed bonds with Chinese gold farmers in high school WoW where they were probably at their second job farming and I was at my second job war gaming, asking them for money in Chinese with strange english spelling. At the time, seemed like gold farming was an awesome career path. still think about that person some days. I am poor

|

|

|

|

Trollipop posted:I read The Good Earth translated to English and formed bonds with Chinese gold farmers in high school WoW where they were probably at their second job farming and I was at my second job war gaming, asking them for money in Chinese with strange english spelling. At the time, seemed like gold farming was an awesome career path. still think about that person some days. I am poor where’s the poem about grinding in azshara? i feel like I’ve been robbed of a contemporary masterpiece that never existed called smth like Scribbled on Someone Else’s Felcloth it’s weird looking back to these ephemeral Internet things where you skid off someone else’s life for a bit. there prob is a poem in there and you could sneak in dry lil jokes about illusory vs real currency, connections etc, reference the racist media freakouts about CCP combination gold farming/organ harvesting dungeons… also I enjoyed that much more positive exam poem! good to see the flip side after the two I posted on the subject e: its actually a particularly interesting poem because Meng was a rather unworldly type who really disliked the exam system and refused to do even the basic local ones for most of his life. his mother managed to pester him into it when he was 40 odd and living hand to mouth. even after he smashed the exams and became a scholar-official he didn’t really do much other than drifting around writing poems so didn’t advance at all iirc. Meng was pretty tight with Li He (you can see the mutual influence) so their exam poems are a cool contrast. the sense of relief in Meng’s poem really shows how Fun he found the system Shogi fucked around with this message at 11:37 on May 28, 2023 |

|

|

|

hope you'll indulge an uncouth double post on Meng Jiao. he's fun to talk about, and in case the SBF wraps up for June it'd be good to finish with some poems After Passing the Examination is even nicer if you play it off against an earlier work: Meng Jiao tr. Burton Watson posted:On Failing the Examination He used the theme of spring's beauty here as well, since that's when he sat the exams, but in this poem it's all much more jaundiced. Watson's translation is a bit of a curate's egg tbh, too loose in places and too literal in others. Meng can be especially hard to translate. None of the English versions of 'Failing the Exam' I've seen feel visceral enough... 'like wounds from a knife' is actually underselling it, it's prob closer to 'sword thoughts run me through'. The lines about birds (western osprey and eastern wren to be exact - maybe some cardinal direction symbolism in there) seem to be about gifted and ordinary people respectively, though where Meng himself fits amidst these flights on fallen feathers is ambiguous. Judging by his other poems about failure, he didn't think originality got you anywhere fast. 'leave them be! leave them be!' - Meng trying to cast dark thoughts aside - could just as easily be read as something like 'cast aside and cast aside again' or even 'returning to the same rejection' - more of a cry of agony at failing this fucker again Meng was very self-aware even if he refused to change much. He could be wry: Meng Jiao tr. Barnstone/Chou posted:Complaints finally, Meng Jiao wrote this one after taking up the post that came of passing his exams, which he'd done for his mother above all: 遊子吟 慈母手中線 遊子身上衣 臨行密密縫 意恐遲遲歸 誰言寸草心 報得三春輝 exile's song heart and skill give threads the shape to clothe her travelling son sew close stitches close to leaving stem slow fear of slow returns how can inch long grass proclaim three months of spring's bright sun

|

|

|

|

Oh no, I didn't think about this thread disappearing, I love it! Here's one I really like the depressed feeling of, though I was curious about 'void' because I know it has religious/philosophical associations. Apricot Garden By Yuan Chen Tr. Angela Jung Palandri Carriages and horses stir up Ch'ang-an's thick dust-- Brought here by the wild wind each spring. In front of my door is only a void, Why plant flowers then to delude others?

|

|

|

|

far from the flowers and revelry of the city over GBS, we contemplate a new post in the dreary provinces. exiled, but alive I've read very little by Yuan Zhen (Yüan Chen in Wade-Giles) so it's lovely to see something new. good choice of poem for the book fair's new era as well, cos one thing I do know about Yuan is he exchanged a lot of nostalgic poetry with Bai Juyi, looking back at their days in Chang'an. some of these are fascinating as they seem to talk past each other and struggle to really connect more and more as time passes. they both came from fairly humble beginnings and got into trouble after initially successful careers - though for v different reasons. will have to dig up the Chinese original for that poem and maybe read more about the poet too, but I wonder if the Apricot Garden of the title is one of Yuan's flights of nostalgia (literally here - nostos algos the pain of returning home in your mind). seem to remember there was a famous apricot garden in Chang'an where graduates celebrated their results. you're def right ASA that 'void' could be a Daoist reference to internal emptiness and calm, but it's interesting that Yuan explicitly places it OUTSIDE himself 'in front of my door'. intriguing, gotta look it up for sure. working this weekend but i wanna dig into it when i get chance. To show how timeless those blurry-edged feelings of nostalgia and immanent loss are we can go back to the Han era's Nineteen Old Poems: Anon tr. Barnstone/Chou posted:14

|

|

|

|

waiting for poetry books to ship overseas has inspired me to contemplate the ancient tradition of posting about posting the history of imperial China is a history of posting stations. they appear from the hazy days of oracle bones and develop through the eras to channel cultural, economic and military forces over vast distances by land and water. post houses provided mail sorting services, portage, messenger dogs, fresh horses, rest and protection for travellers with official permits, bulletin boards to scrawl poems on, eunuch corpse storage, tempting opportunities for bandits, and hilariously dangerous frontier posts for your exile after getting on the wrong end of the argument about the eunuch corpse storage. Yuan Zhen's exile to Sichuan got him into the postal station poetry game: Yuan Zhen tr. Ao Wang posted:Two Poems on the Wall of Luokou Post Yuan's reading the messages on the walls and reflecting on life - his own little personal current and the deeper political sea. Cui (Shao) and Li (Fengji) from the first poem are the second's 'two stars', emissaries travelling south to Nanzhao - Tang China was at war with the Tibetan empire and their Abbasid allies and was working on getting Nanzhao to switch sides. Wang (Zhifu) was a poet Yuan wasn't familiar with, who'd been travelling with our pal Bai (Juyi). Bai is also the 'Hanlin scholar'. he and Yuan were great friends and maybe lovers - more on this another time maybe - and had made a doomed 'Green Mountain pact' to retire together as Daoist recluses one day. in these poems Yuan uses the station walls to trace his connections to his friends, the future and the wider world as he goes into the unknown. Bai and Yuan were separated by exile and tribulations on both sides but exchanged poems and gifts via post throughout their lives, with Bai continuing to address poems to his friend even after Yuan died. Bai wrote of him, 'each time I arrive at a post house I first dismount, following the walls and circling the pillars for your poetry'. a quick note here: Bai Juyi's courtesy name marking his coming of age was Letian, while Yuan Zhen's was Weizhi. on to a selection of their postal poems: Yuan Zhen, tr. after Ao Wang & AM Shields posted:On Seeing Letian's Poem here Bai's words, perhaps copied by some admirer who found them comforting, bring Yuan a flash of hope in tough times Bai Juyi, tr. after WU Shuling posted:A Poem Posted to Yuan the Ninth Having Seen his Poem about Pomegranate Blossom near Wuguan Pass Bai writes about flowers that weren't blooming when he passed by, conjured up nonetheless by Yuan in poetry Yuan Zhen tr. Ao Wang posted:In Response to Letian, Who Often Dreamed of Me a malarial and feverish Yuan feels guilt at the loss of their earlier weird connection through dreams Bai Juyi tr. AM Shields posted:excerpt from Poem in Place of a Letter nostalgic musings from Bai Juyi. Yuan had lived near Xingshan temple in the Jing'an quarter.

|

|

|

|

Man, what a beautiful lost tradition. What era were these selections written in? The one with the tiger tracks is so powerful--were these the equivalent of graffiti, just a poet using public space or were they commissioned?

|

|

|

|

A Strange Aeon posted:Man, what a beautiful lost tradition. What era were these selections written in? The one with the tiger tracks is so powerful--were these the equivalent of graffiti, just a poet using public space or were they commissioned? 100% agree on the tiger tracks poem btw, probably my favourite of Yuan Zhen's so far graffiti and epistolary poems are interesting anyway, but there's something special about this cultural combination. it survives in a small way today through poems on metro station walls. v long history to it, but these particular ones were written during the mid-Tang burst of creativity as China recovered from the An Lushan rebellion (discussed earlier when we looked at Li Bai's poem about the waterfall at Lushan). I think all of the station-wall and epistolary stuff I posted dates to 809-815 CE based on when Yuan and Bai were travelling. though the post system was critical to the bureaucracy and accordingly controlled by a meshwork of permits and regulations, post station poems were more of an emergent phenomenon within it and usually had nothing official about them. poetry circles wrote them to stay in touch and popularise their styles, or people would pass some of the dead time at the post station reading and practicing their calligraphy. tying several threads together, philosophical graffiti by a Song dynasty polymath: Su Shi, tr. Burton Watson posted:Written on the Wall of West Forest Temple

|

|

|

|

a month ago, after promising to look up Apricot Garden in the Chinese, I ordered Palandri's book on Yuan Zhen. it arrived this week and...it doesn't have Apricot Garden in it. as it turns out I already had the book the translation appears in, an anthology called Sunflower Splendor. unfortunately that doesn't have the original Chinese either. but it did provide a page reference to a 1961 repro of the enormous 18th century Tang poetry collection, the Quan Tangshi. couldn't find that edition online, but after some digging I managed to find what I think is the poem on the Chinese Text Project's scan of the QTS. Characters: 杏苑 [xìng yuàn, Apricot Orchard] 長 安 車 馬 客 , 傾 心 奉 權 貴 . 晝 夜 塵 土 中 , 那 言 早 春 至 . Middle Chinese reconstruction: djhiɑng qɑn tchia ma kaek kiuehng sim bhiong gyuehn giuh'i djiou ia djhin to djiung na ngiaen tzau chuin ji Pinyin and literal meanings: cháng ān chē mǎ kè [Chang'an carriages and horses visitor] qīng xīn fèng quán guì [outpour heart{qīng xīn = 'fall in love'} offer power noble {quán guì = 'powerful officials'}] zhòu yè chén tǔ zhōng [day and night dust within {a reference to the 'heart of dust', mentioned in the OP? or a sense of utter, helpless longing?}] nà yán zǎo chūn zhì [those words early spring arrive] Angela Jung Palandri's translation again: Carriages and horses stir up Ch'ang-an's thick dust-- Brought here by the wild wind each spring. In front of my door is only a void, Why plant flowers then to delude others? this one has me a bit stumped tbh, it seems very obscure and unless the translation is absurdly loose there must be idioms and allusions I'm missing, or perhaps this is an excerpt of something larger and Palandri is freely paraphrasing the whole thing. i don't think i'm looking at the wrong poem entirely cos there are a lot of similarities (line 1 shares a lot of words, there's an intensified reference to dust, etc). i was expecting the characters xū, kōng or both for 'void', though - without them I don't think there's a clear religious reference here. it looks to me like Yuan is making a complex and abstruse complaint about the hollow falsehood of Chang'an's palace intrigue and its grasping scholar class, whose words 'plant the flowers' (a triple meaning here maybe - zhōng means within but zhòng means to plant or cultivate and zhǒng means seed) of 'early spring' while the reality, inside and out, is barren dust. Palandri's book on Yuan backs this up as he seems to have been an idealistic, crusading kind of man who was extremely intelligent but full of himself and a lot better at making enemies than heeding warnings e: i should probably point out a couple of things: 1) the hardest, most important imperial exams were held in springtime Chang'an during Yuan's life; 2) there was an apricot orchard in the ci'en temple in Chang'an in which the new jinshi gathered after passing. think i alluded to this before but not with much certainty. i've now looked it up and Can Confirm Shogi fucked around with this message at 18:58 on Jul 22, 2023 |

|

|

|

I first encountered that poem in the Sunflower Splendor anthology you reference, and the detail of the original vs the translation just fills me with doubt about the validity of any translation I read! Like, where did the 'void' come from?? I really like the poem in English but from what you posted, the translator took such liberties it's hard for me to figure out what the original author was trying to communicate. I really appreciate the deep dive, by the way! They're such little jewels with so much to unpack I fear I'm getting more static than signal sometimes but be that as it may, the static is so intriguing I keep returning.

|

|

|

|

A Strange Aeon posted:doubt lol yeah, was in two minds about posting it cos it's the most confused i've been by a translation in ages and I know I'm missing something. but much as i don't want to disillusion anyone, you do find some translations which walk the line between 'creatively interpreting and expressing the poet's voice' and 'ghostwriting fanfic'. it's part of the game. Palandri was an advocate for Yuan Zhen's literary importance and spent months (years?) studying his life and work, which in a way can make you more prone to strange, creative translations as you pull in elements from your wider knowledge and the image of this dead poet in your mind. again though, my credentials are 'some rear end in a top hat' and Tang poetry often uses euphemisms and classical references, both as conventions and as an attempt to avoid political consequences. there are common ones like how 'clouds and rain' means 'sex', how 'peach blossom spring' summons up a proto-isekai utopia (see OP) or how namedropping a Qin dynasty emperor/courtesan/etc is usually a coded criticism of a contemporary counterpart. there are more difficult ones too, and sometimes if you miss one it can make a line read as nonsense. having said that, Palandri tells us that Yuan was a fierce proponent and exemplar of clarity and communicative power in writing, who helped overturn the artifical, comically mimsy and prettified prose style that had taken hold of even official communications (hang on got to balance and rhyme my allusions to cassia flowers before i post my begging letter for reinforcements). so it's a little less likely that Apricot Garden is a tangle of impenetrable references. not impossible though! Yuan was still a Tang poet in the end. read this to die: https://colips.org/conferences/ialp2019/ialp2019.com/files/papers/IALP2019_064.pdf some further thoughts on the translation: -got to free myself from translating line by line. Palandri kinda takes all the concepts together and parses them in a new way; -tho qīng xīn can mean 'fall in love', maybe we should take this line MORE literally as 'outflow heart sacrifice power noble'. Chang'an is pouring out its heart and power to the nobility - ie, the carriage wheels and rushing feet gouge flying dirt from the same land that grew the apricot orchard; -chén tǔ is one more character than you really need to say dust, it's kind of like 'earth dust'. this is a restricted form so Yuan will have used two characters for a reason. so again strictly literally the line is 'daytime night earth dust within'. chén is just below fèng (line 2 and 3, character 3). now, fēng chén (different tone on feng, but...) does mean 'windblown dust' and can be used to mean 'life's hardships' or even 'prostitution'. so that might be where the 'wild wind' in the translation comes from and it could be a very sly dig at the official class too; -thoughts from a friend: "chen tu zhong to me reads as 'in the centre of earthen dust', not really within, but 'centre', cause I'd imagine he would use 'qin' for 'in' or 'within' - so to my modern eye it reads like 'at the eye of the storm'. perhaps: Chang'an receives guests by carriage, those in love with/devoted to power, and the bluster of the capital day and night, like a whirlwind of dust. and the last line looks to me 'this is what happens in spring, the usual words said by officials'. like you said, the flowers line is prob a poetic way of translating that bit. i can't see the door void thing though. but Palandri might have more insight on the era. sounds like Yuan knew his future was hosed but don't see where he says that'" -so we can't figure out where 'in front of my door is only a void' comes from, lol. you could maybe argue that zhōng is being used to mean 'hollow' but it's a stretch, and turning 'day and night earth' to 'in front of my door' is even more of a stretch. i do really like how line 3 sounds in the original pronunciation tho. anyway, gonna come back to it sometime cos i'm invested now. best clear the static a bit first with a different poem tho. this is a loving wonderful Du Fu poem that's relatively easy to get into English, though you can't bring all of the fun playing around with structure and rhyme from the original Du Fu, tr. Stephen Owen posted:Crazy Man Original: 狂夫 [kuáng fū - mad man/labourer] 萬里橋西一草堂,[wàn lǐ qiáo xī yī cǎo táng - ten thousand li bridge west one straw cottage] 百花潭水即滄浪。[bǎi huā tán shuǐ jí cāng làng - hundred flowers pool water namely Azure Waves {cāng làng - a Chan-ish metaphorical place of retreat, you see gardens named for this a lot}] 風含翠篠娟娟淨,[fēng hán cuì xiǎo juān juān jìng - wind contain jade-green dwarf bamboo beautiful graceful clean] 雨裛紅蕖冉冉香。[yù yì hóng qú rǎn rǎn xiāng - rain wet red lotus slowly softly fragrant] 厚祿故人書斷絕,[hòu lù gù rén shū duàn jué - thick salary old friend {'old friend' also = euphemism for the dead} letter cut off vanish] 恆飢稚子色淒涼。[héng jī zhì zǐ sè qī liáng - permanent hungry young child look grim cold] 欲填溝壑惟疏放,[yù tián gōu hè wéi shū fàng - desire fill in deep ditch only negligence frees] 自笑狂夫老更狂。[zì xiào kuáng fū lǎo gèng kuáng - self laugh mad man old still more mad] Shogi fucked around with this message at 15:00 on Jul 23, 2023 |

|

|

|

I don't have a lot to add to this thread as a complete novice but all this stuff on translation theory, breaking down the poems, and so on is really cool!

|

|

|

|

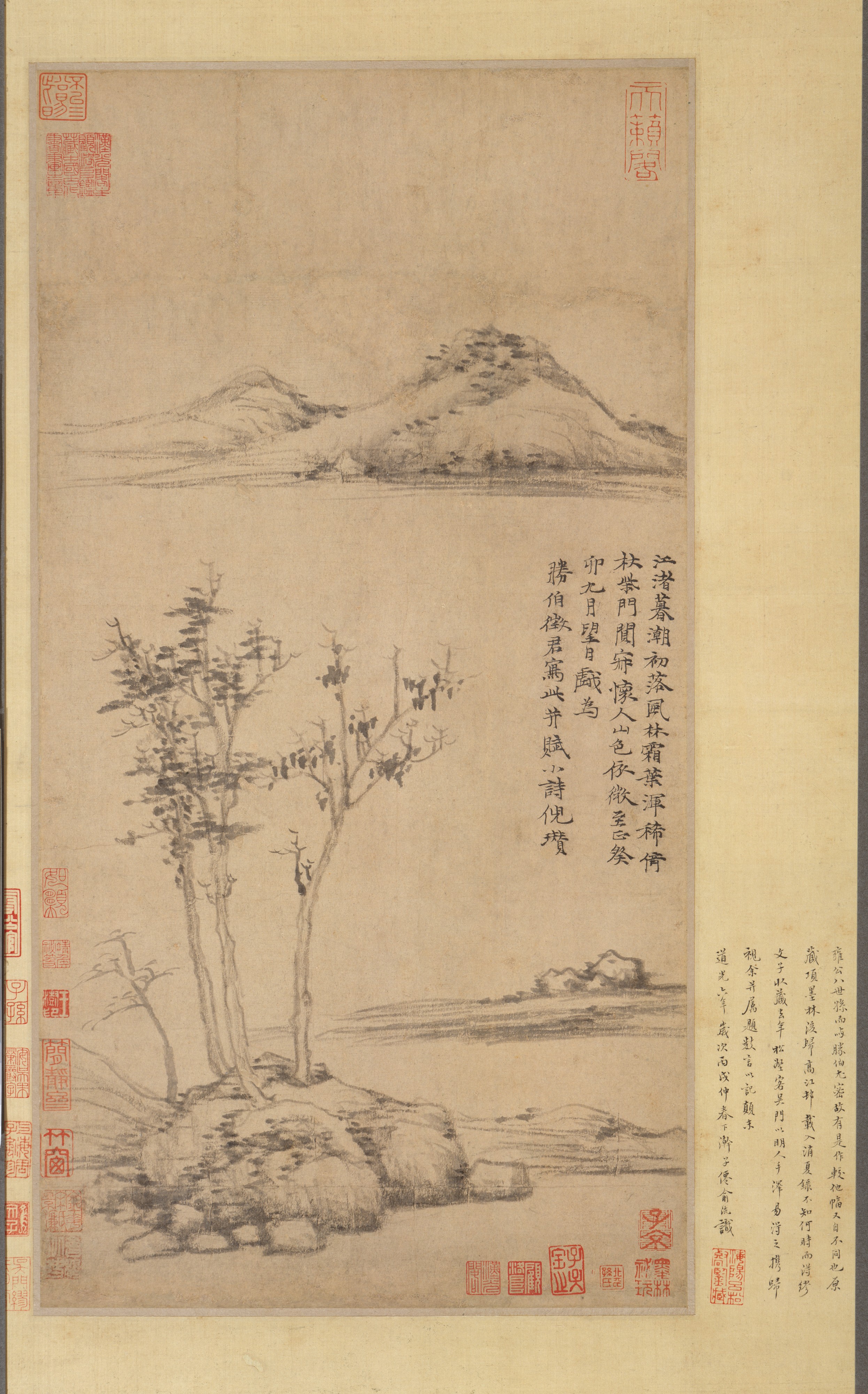

Leraika posted:I don't have a lot to add to this thread as a complete novice but all this stuff on translation theory, breaking down the poems, and so on is really cool!  Ni Zan was the Bob Ross of the late Yuan and early Ming. he lived a strange life in a chaotic time and aimed for a studied, bland, almost icy calmness in his paintings. on this scroll, titled Wind among the Trees on the Riverbank, he wrote: Ni Zan posted:On the riverbank, the evening tide begins to fall;

|

|

|

|

Man, the concision in that poem is excellent. Everything adds up to the last line which is one of those memorable images that stick with you. Was it common for there to be art and poetry together like that?

|

|

|

|

Ni Zan is considered a master for good reason, but the Yuan dynasty arts are relatively neglected in English-language academia. it's a shame because the impact of the Mongols led to some interesting stuff, including Yuan opera and the death-n-destruction sāngluàn genre of poetry (literally something like 'grief-chaos' poetry) poetry and painting were fingers on one hand, yeah. remember, calligraphy was king and you'd be poo poo hot with a brush by the time you'd perfected all those line weights and stylish flowing shapes that made your prose or poetry look good, expressing your personal character in written figures. not a 1:1 comparison, but it's a little like illuminated manuscripts in medieval europe dialled up to 11 by the complexity of Chinese characters and the extreme cultural importance of poetry. aspirants did often copy works by old masters to sharpen their skills (and sometimes got very, very convincing at it - forgery/attribution in Chinese art is a genuinely entertaining topic and remains tricky today) Ni Zan i spose would be classified by later scholars as a 'literati painter', someone more interested in expressing his emotions than capturing beautiful representative scenes. here's another example of painting-poetry by the heartbreakingly talented psychotic murderer Xu Wei, who considered himself a calligrapher above all:  Xu Wei posted:Grapes

|

|

|

|

Wait, you can't drop that and leave it unexplained (if you wouldn't mind)

|

|

|

|

chaos poetry, forgery or psychotic murder?  i did post something years ago about forgery in chinese art. might come back to it sometime rolling with murder - well, today Xu Wei would almost definitely get diagnosed with something like schizoaffective disorder. Yuan Hongdao posted:...his poems are sometimes full of laughter and sometimes of anger; they sometimes read like roaring water gushing through a narrow valley, the subtle sound of plants sprouting from under the soil, the weeping of a widow in the middle of the night [guafu zhi yeku], and the [sighing] of a lone traveler after waking up in a cold night. he was a child prodigy, and recognised as one when his work 'Release and Destruction' made waves in Shaoxing city. like many of that type the pressure seems to have got to him. his mother, who had raised him alone, died right at the height of the hype about him, when he was 14. he started drinking heavily, and his first wife died about four years after they married. he failed his exams, then failed them again and again and again. this wasn't how his life was meant to go. he joined the army and fought japanese pirates with surprising distinction and creative tactics. the general he served with got tangled up in war politics and got arrested. Xu became convinced he was next and developed florid paranoia. he drilled holes in his own head, pasted his balls with a hammer and tried to kill himself with an axe. he started to think his third wife was in on the plot, and sleeping around. he killed her and spent years in prison before a friend and admirer got him freed on grounds of insanity. he wrote guilt-ridden poems and a play called Singing in Place of Screaming. he eventually died in poverty. Shogi fucked around with this message at 17:13 on Jul 26, 2023 |

|

|

|

That's less fun than I thought it might be  but yeah that was what I was talking about.

|

|

|

|

*taps the Uplifting Life Stories sign* he’s like the late Ming’s Vincent van Gogh in a lot of ways, only with pirates and a suspicious amount of death surrounding him. his style and self-conscious weirdness was immensely influential later, to everyone from the Eight Eccentrics to Zhang Daqian “Xu Wei, about his own portrait” posted:At birth I was fat. When I was twenty, I was so skinny that my clothes overwhelmed me. By the time I was thirty, I had gradually fattened up again. Now we have this silly fellow pictured here. I was not aware of the years passing. Now how can we know that this silly fellow today will not become skinny again, just like the mountain marshes that dry up? Trying to grasp me through this picture would be like notching the side of your boat [where the sword is dropped], or watching the tree stump [for another hare to dash against it]. Is he a dragon? A pig? Is he a crane? A duck? Is he a flitting butterfly? Is he a weighty Zhuang Zhou? Who can know his beginnings?

|

|

|

|

I know it's slightly outside of the purview of this thread, being more of a general satire rather than poetry, but having recently seen a translation of the work of a Qin dynasty writer reflecting on the Imperial exams, figured I might as well pass it along. Translated by multiple authors through multiple languages, so not sure how much of the original flow remains, if any.Pu Songling posted:When he first enters the examination compound and walks along, panting under his heavy load of luggage, he is just like a beggar. Next, while undergoing the personal body search and being scolded by the clerks and shouted at by the soldiers, he is just like a prisoner. When he finally enters his cell and, along with the other candidates, stretches his neck to peer out, he is just like the larva of a bee. When the examination is finished at last and he leaves, his mind in a haze and his legs tottering, he is just like a sick bird that has been released from a cage. While he is wondering when the results will be announced and waiting to learn whether he passed or failed, so nervous that he is startled even by the rustling of the trees and the grass and is unable to sit or stand still, his restlessness is like that of a monkey on a leash. When at last the results are announced and he has definitely failed, he loses his vitality like one dead, rolls over on his side, and lies there without moving, like a poisoned fly. Then, when he pulls himself together and stands up, he is provoked by every sight and sound, gradually flings away everything within his reach, and complains of the illiteracy of the examiners. When he calms down at last, he finds everything in the room broken. At this time he is like a pigeon smashing its own precious eggs. These are the seven transformations of a candidate. Pu Songling here is probably better known for his work, Liaozhai zhiyi - Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, which is part of a genre of strange or supernatural tales which are somewhere in-between horror and "wouldn't that be super messed up?" stories.

|

|

|

|

Jossar posted:I know it's slightly outside of the purview of this thread, being more of a general satire rather than poetry ... lol that's awesome, the seven ages of examined man. i love how passing isn't even considered a possibility. oh and bring on the prose fiction, satire, theatre etc. fits the subforum mission statement and 'poetry' is an especially fuzzy category in China anyway. excuses in early: i'm ill so this post might end up being unreadable. but once again there's a bit of a hidden theme to the topics in the thread so i wanted to have a go at pointing it out. lately we've had Yuan Zhen, the vagaries of translation, chuanqi short stories like the Strange Tales, Xu Wei and, as always, exams. when the big beasts of Tang poetry walked the earth - Li Bai, Du Fu and all that - fiction was considered lowbrow. sure it was popular nonetheless, with folk legends and fairy stories going back centuries, but it wasn't worthy of study. just not the kind of stuff that improves characters and lifts spirits. though you wouldn't be examined on prose fiction, by Yuan Zhen's time it had become customary for candidates to demonstrate their range of skills by writing it for their sponsors. Yuan, as we've seen, was a very talented writer and a proponent of the classical prose movement that aimed for clarity and simplicity in writing, in place of the exquisitely purple and restrictive style which had taken hold over time due to material reasons too complex to explore here (Chinese as a unifying language of administration across a huge area had become quite artificial). maybe it was as a warm-up for his exams that he wrote one of the first and most famous chuanqi. popularly known as Yīngyīng zhuàn (The Story of Yingying), this was a chimera - an ambiguously autobiographical star-crossed-lovers story with epistolary elements, which Yuan threaded around a poem titled Huìzhēn shi (Meeting the Immortal). you can read it in translation courtesy of Stephen Owen starting at page 540. Yuan Zhen, tr. Stephen Owen posted:After another long wait, the daughter came in. She wore everyday clothes and had a disheveled appearance, without having dressed up specially for the occasion. Tresses from the coils of her hair hung down to her eyebrows and her two cheeks were suffused with rosy color. Her complexion was rare and alluring, with a glow that stirred a man. Zhang was startled as she paid him the proper courtesies. Then she sat down beside her mother. Since her mother had forced her to meet Zhang, she stared fixedly away in intense resentment, as if she couldn't bear it. this story's enduring popularity and myriad of adaptations might be explained by its weirdly timeless interpretive depth. Zhang is an odd protagonist. we're told he's a disciplined Confucian gentleman but he's shown as a cowardly, selfish and arbitrary prick. every virtue he supposedly has is contradicted by the story in a way that lines up too well to be accidental. he abandons the woman he loves and justifies it by saying she'd destroy him, or his official career. Cui Yingying, the apparent object of his affection, comes across as much more self-possessed and wise. we know Yuan Zhen had a love affair before his marriage that affected him deeply, just like Zhang. Angela Jung Palandri notes that zhēn, usually translated as 'Immortal' or 'Holy One' could be translated instead as 'truth' or 'reality'. a meeting with truth, which Zhang turns away from. the line between fiction and reality in this story isn't clear. this applies also to Xu Wei's own strange tales. he wrote a set of four plays called Sisheng yuan (Four Cries of a Gibbon), each one about a person who broke social conventions, which as a whole explore how identities are made and help to build his own myth as a bizarre eccentric. Xu Wei, tr. Shiamin Kwa posted:I was a woman till I was seventeen, again the examinations come up, as one of the protagonists dons her dad's clothes and sits them in disguise. Yuan Zhen aced all his exams while Xu Wei never got through them. their weight, the burdens and expectations they represented, the dreams to which they seemed to bar the way, left marks on both writers though, they twisted into their identities in ways they could only try to unpick through fiction. those drat exams (Ed: here i ran out of juice, stopped mid-thought and hit post. so to conclude:) what was reality for a Yuan Zhen, or a Xu Wei? the simple life, with that poverty and obscurity so many poets assumed as ragged mantles taking its true shape, lending no literary cachet, just freedom from posterity and restless hopes? no doubt they'd each have had their view on that. what do we find of the real men in the lives they managed to live - thwarted crusader and genius-turned-murderer - and in their poetry and fiction? what was it in China, in this strange world we share, that made a creature like Yuan Zhen or Xu Wei, and how much choice did they ever get in who they were? then come the translators, shaped by their own exams and expectations, to reinterpret them again. Shogi fucked around with this message at 21:04 on Aug 1, 2023 |

|

|

|

Leraika posted:I don't have a lot to add to this thread as a complete novice but all this stuff on translation theory, breaking down the poems, and so on is really cool! this is a low-key GOAT thread, gotta say. very neat. got me reading that whole anchor book, as well as the complete li he. i hadn't read a single chinese poem until a few months ago. definitely easy to go down a rabbit hole, though, as i'm pretty ignorant about (especially ancient) chinese culture and history and i thirst for context.

|

|

|

|

the history of china was a very good podcast until it fell into the monetization hole and ruined itself with a combination of ads and every third episode being behind a subscription

|

|

|

|

the search for context never really ends, it's a rabbit hole even for Chinese academics it's not for me to tell anyone how to study Chinese history - wish I could help more. chasing references while you're reading about the arts helps gradually build a sense of things, esp if you can exploit an OpenAthens account for access to journals. never come up with a better system myself, just a mix of that and pestering people who know more than me. since we're here - chinese history doesn't have a major presence on SA to my knowledge, but c-spam's pre-modern history thread is excellent at its best and well worth mining for China posts. got a couple of books to consider - maybe they're not obvious picks for studying history, but imo they're good ways to get an idea of old China. Edward Schafer's The Golden Peaches of Samarkand is a sprawling, disorganised mess of a reference book about exotic imports to Tang China. not sure if you can get it free online without institutional access, but this book sold well back in the day and you should be able to get a cheap used copy. it's full of informative tangents on every Tang topic going and, critically, it's well-written. fluent and engaging with lots of passion. there are tons of Western academic books on China which are arranged better than this and yet are much harder to learn from because they're so dry and boring. Jacques Gernet (tr. HM Wright)'s Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276 is a vivid snapshot of life in Hangzhou in the (very) late Song. a bit dated in parts now, but a very breezy and evocative read about a time that already feels quite distant from the high Tang. the Spring-and-Autumn and Warring States periods (~770-221 BCE), culminating with the Qin wars of unification, hold a lot of the keys to context (not least Confucius) but you won't find much history in translation. I'd go with the trusty Cambridge History of Ancient China first rather than pumping yourself with a massive shot of many zhan guo ce tbh. from there you're ready to dive into the arguments about which translations of dao de jing and the Analects are best, and if you're a real sicko you can start looking at the other classics. Bai Juyi had a famous lil question about the DDJ: Bai Juyi posted:dú lǎo zi [Reading Old Master] or, only a tiny bit less literally, something like: "The speaker does not know, the knower does not speak," this saying I learned from Laozi. If the Way was what Laozi knew, whence the nerve to write five thousand words?

|

|

|

|

Hey, found one with an original set of characters for once! Kong Shangren is mostly known for writing a play complaining how much it sucks that the Qing dynasty took over China, but he also took the time to write a poem on how glasses are pretty neat. Kong Shangren posted:西洋白眼镜,市自香山墺。 The translation I read gave: Translation posted:White glass from across the Western Seas

|

|

|

|

Jossar posted:Hey, found one with an original set of characters for once! Holy poo poo, what a great poem! I love the specificity and as a glasses wearer how relatable that is.

|

|

|

|

Jossar posted:glasses are pretty neat what a cool poem. great little insight into the time, which seems like Kong Shangren's big strength. i only knew him for the play you mentioned, The Peach Blossom Fan, which is another fun window on history. i've started looking at his poetry cos of your post. the translation of Trying On Glasses looks good - I think it's by Richard Strassberg. in case you wanna see how the poem sounds, with its very strong rhyme scheme (ào/qiào/miào/shào): xī [west] yáng [ocean] bái [white] yǎn [eye] jìng [glass] shì [market] zì [from] xiāng shān ào [the Macao region] zhì [make] jìng [lens] dà [large] rú [as if] qián [coin] qiū shuǐ [calm autumn waters - an idiom for pretty eyes] hán [include] shuāng [two] qiào [opening/solution] bì [cover] mù [eye] mù [eye] zhuǎn [turn] míng [bright] néng [can] chá [see] háo [drawing brush|general term for small fraction] mò [tip] miào [wonderful] àn [dark|secret] chuāng [window] xì [delicate] dú [read] shū [book] yóu [like] rú [as if] zài [in the middle of] nián [years] shào [young] looking at Kong's poetry, it's funny you picked one about an item you wear. 'clothes make the man' seems to have been a big idea in the late Ming/early Qing - stuff about clothing and identity is all over Xu Wei's Four Cries of a Gibbon eg: Xu Wei tr. Shiamin Kwa - from The Mad Drummer Plays the Yuyang Triple Rolls posted:Cao: Rube! As an official drummer you have your own designated uniform; why aren't you wearing it? Go, change! from The Heroine Mulan Joins the Army in Place of Her Father posted:Mulan: Kong Shangren was born in the early years of the Qing dynasty, ruled by Jurchens who had been subordinate under the Ming. they consolidated and enforced a new Manchu identity. that shaved in front, long at the back hairstyle you see in a lot of kung fu movies was a traditional Jurchen style which Qing prince regent Dorgon (literally 'badger') made mandatory for non-clerical Han men in 1645 on pain of death. the 'haircutting order' was a lil bit controversial and resulted in a whole lot of people getting the chop a bit lower down. so you really needed to show your loyalty to Qing visibly, through your hair and clothes. we've got The Peach Blossom Fan so we can infer Kong's thoughts on this, and we know he was familiar with the outward performance of identity. some of his poems about his friends use clothing and allusion to imply Ming loyalism: Kong Shangren, tr. Guojun Wang posted:He did not escape from the Qin, nor does he live by picking vetches; Picking vetches - a reference to a myth about Shang loyalists who fled to the mountains from the Zhou; Escape from the Qin - a nod to Tao Yuanming's Peach Blossom Spring (a dreamworld of magic which displaced people found and lived in, see OP &c); Broad sleeves - so Kong's friend isn't living in exile, but broad sleeves were a feature of Han scholarly dress in the Ming era, not so much the Qing. an expression, metaphorical or not, of identity. at other times Kong explicitly compares old-style and Qing clothing: quote:Seeing Monk Shuju Return to Jinling knowing about this aspect of Kong's mind, the effect of the new glasses becomes even more interesting - they really are a portal back to his youth Shogi fucked around with this message at 13:09 on Aug 20, 2023 |

|

|

|

Thanks Shogi for giving a bit more of an expansion on the context and further providing some of Kong's other poems! I seem to be finding a bunch of Chinese poetry floating around recently so I present this one by Su Shi, who Shogi also mentioned earlier in the thread: Su Shi, Translated by Arthur Waley posted:Families when a child is born Su also has a fun story attached to him about how he wrote a grandiose poem bragging about his spiritual accomplishments, saying that the eight winds could not move him and sent it to a master Foyin, who responded with a single character that reads as either "nonsense" or "fart". When Su went to complain, Foyin then responded: "The eight winds cannot move you, but one fart sends you across the river."

|

|

|

|

an early example of the gifted child's lament there from Su Shi lol. reminds me a little of Meng Jiao's various complaints that you couldn't get ahead with good poetry. it's an intriguingly bitter poem to dedicate to a newborn. here we have an opportunity to ramble about history. probably this was written somewhere around the time of 1079 CE's wutai shi'an (or Crow Terrace Poetry Trial), a protracted wrangle which nearly cost Su Shi his head. this was ostensibly over one sentence in a routine thank-you note: Su Shi, tr. Yugen Wang posted:Excerpt from the Huzhou memorial this was taken by the Investigating Censor as an attack on the chief ministers and parlayed into a general trial of the political content of Su's poetry. obviously this wasn't really about a catty humblebrag in an obligatory note expressing 'gratitude' for being exiled. Su had spent years trying to centrist dad his way through the great political-economic struggle of the era, and was considered one of the leading 'moderate anti-reformists' opposing Wang Anshi's New Policies. Wang attacked the Song state's traditionalism and its distant, inefficient and unfair treatment of its commoners as causative factors for its military struggles. his reforms looked to specialise education, institute loans to peasant farmers, bash monopolies and middle-men, restructure land tax, village defence, labour organisation and the army, control government spending and generally increase direct state involvement in everyday life. big sweeping stuff. caused a lot of arguments over implementation and philosophical underpinnings. the Song government was run by academics, and this was a time of rabid debate between Confucianist schools that even included some proto-historical-materialist ideas, so you can imagine that the level of ivory tower backstabbing over something like this was legendary. factional power swung back and forth, with one persecuting the other in turn and 'moderates' often getting the worst of it. Su Shi had already been banished for his anti-reformism once while Wang Anshi was in the ascendancy. rather than a grim contention between malaria and the Tanguts for pwning rights though this was a pleasant exile to the shore of Xihu[West Lake], following in the footsteps of Bai Juyi as governor of Hangzhou. he was popular with the people, doing good works and developing as a poet, picking up his pen name of Su Dongpo[east slope] from the aspect of his small farm there. Su was eventually recalled from this post as the reforms struggled to be born and Wang Anshi's prominence faded, but Su remained wary for good reason. he was banished again, more harshly, as magistrate of Huzhou, then arrested by marshals after his unfortunate note. the Song had never executed an official for 'defaming the throne', but it's clear that Su was in real danger - his family hurriedly burned all of his papers they had and Su considered drowning himself to avoid arrest. in the end he was interrogated, possibly beaten, cross-examined and scrutinised for around four months and sentenced to two years of penal servitude. Su Shi believed in the Confucian ideal of remonstrance. you were supposed to criticise misrule in your poetry. so let's review some of the offences in his 'Mountain Village' series of poems: Shu Dan, for the prosecution, tr. Yugen Wang posted:Your Majesty loaned money to benefit the poor people, and Su Shi wrote: "The only gain was that the accent of their children had improved; / for the better part of the year they had stayed in the city.” Your Majesty tested officials on their understanding of the law, and Su Shi wrote: “Reading ten thousand scrolls of books without studying the law, / ones chances of bringing about Yao and Shun-like sage rulers are doomed." Su admitted that he had intended to, eg, "ridicule the harshness of the salt laws", but implicitly criticised his accusers' literal reading of his poems and lack of concern for their mountain-village social context and exploration of common suffering. Eg: Su Shi, in his defence, tr. Charles Hartman posted:The fourth poem of the series reads, so he was, in the end, quite open about his criticism of policy but denied criticising intent as such. you can kinda see how he must have been an irritating figure for reformists. his younger brother Su Zhe had pleaded to the emperor for clemency on the grounds that "His old poems ... had already been circulated out of his control. I sincerely regret that my brother, blinded by stupidity and self-complacency, did not realize that literary writings could easily go beyond the boundaries of propriety, and that although he really wanted to amend his errors, he has already fallen to such depths that the situation became almost irremediable". But on the way to serve his sentence as an exile in Huangzhou, Su Shi stopped to see a friend and composed a poem: Su Shi, tr. Yugen Wang posted:I myself am Zhuchen's former prefect;

|

|

|

|

I hope this thread never dies, that last little poem after reading all about the context of the writer ends up even more stunning. What a great juxtaposition of the state banging on doors at midnight with the Apricot Blossom.

|

|

|

|

the meditative quality of chatting poo poo about chinese poetry never gets old once it's got you. this thread could go on til something awful draws its last dead gay breath and hardly scratch the surface of the poo poo there is to chat. who knows? no effort post today, but it's about time for a poem by the storied statesman and general Cáo Cāo, founder of Wei. duǎn gē xíng (A Short Song) is said to have been written for a feast just before the Battle of Red Cliffs, in the winter of 208 CE. this translation is as literal as you can get while retaining English grammar - you can find poetic translations eg by Stephen Owen and there's even an interesting one on Wikipedia with the original characters. Cao Cao, tr. Michael A. Fuller posted:Short Ballad *Fuller translates as 'reed-organ' the sheng, a fascinatingly fiddly musical instrument: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkkA5yWrvww Cao Cao lost at Red Cliffs and was unable to conquer the south to reunify the old Han lands. the Three Kingdoms period would follow. about 850 years later, Su Shi sailed by Red Cliffs fresh from serving his Crow Terrace Poetry Trial sentence - the Cliffs aren't far from Huangzhou - and wrote an interesting ode reflecting on some of these same themes

|

|

|

|

I know Mao wrote poetry; is this something that's still expected of the leadership/political class?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 9, 2024 08:32 |

|

that's a really good question. the short answer is a qualified yes. the long answer will be far from definitive as my knowledge of contemporary poetry is feeble, and i'm gonna struggle to do any real reading for a while since i'm posting from my tomb inside a giant shitheap of work and academic commitments. but the ways in which the ennobling qualities of poetry have endured and changed is interesting. it's worth having a look at poems by leaders of the People's Republic. starting with Mao, like ASA mentioned: Mao Zedong, tr. Willis Barnstone posted:Snow this poem was written around the time Japan surrendered in 1945. Mao was probably inspired by his flight to negotiate with Chiang Kai-shek - seeing the early snow on the landscape from above, contemplating ancient history and preparing to write part of the future. the powerful final couplet contains a quotation from Su Shi's Reminiscing at Red Cliffs, mentioned off-hand at the end of my last post - 风流人物 fēng liú rén wù smth like 'talented and romantic characters'. the Su Shi poem is extremely famous in China and a lot of people would have caught the reference. Mao's ability to weave his knowledge of China's history and culture into genuinely good new poetry really helped to legitimise him as a leader imo. Mao's premier/face/human shield, the fascinating Zhou Enlai, also composed poems: Zhou Enlai, tr. badly by Shogi posted:Arashiyama in the Rain Zhou wrote this piece about finding clarity around 1918 while he was studying in Kyoto, and it's now engraved on a memorial in a cherry grove at Arashiyama. unlike Snow, it's associated with Chinese-Japanese friendship. the future of China was uncertain as Zhou wrote this, and he was discovering Marxist ideas. he was a big admirer of Mao's poetry too, and optimistically recited In Praise of the Winter Plum Blossom to Richard Nixon: Richard Nixon posted:And he pulled out the little red book, and read ... actually a very beautiful poem, and the meaning which he gave to it is quite interesting. Deng Xiaoping was of course a pragmatist and not known for writing or even quoting poetry. his era was about when the Misty Poets became prominent, with their syncretistic, surreal, obscure pieces often expressing individualist yearnings and political anger, eg: Bei Dao, tr. Tony Barnstone posted:Nightmare his successor, Jiang Zemin, was a massive poetry dude though, quoting it extensively and writing his own, often using poems in a very traditional Chinese way as a way to build his image and conduct diplomacy. in a rather adorable move he once presented Fidel Castro with a poem comparing him to a weathered pine tree. Grandpa Jiang is remembered fondly by a subset of Chinese zoomers, known on the socials as frog fans. today's man, Xi Jinping, is an all-round academic who has advocated for the teaching of classical poetry to continue. he too has used poetry in traditional ways, as you can see here: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202108/1232508.shtml e: can't spell Shogi fucked around with this message at 22:56 on Sep 14, 2023 |

|

|