|

Is it important, or not important, for the sake of your analogy, that in many games the GM is not the sole arbiter of what it means that the king has red hair? Including sometimes players having full power to decide (ad-hoc or otherwise), individually or collectively, what an otherwise still undetermined setting or plot detail will be, without the GM having veto power? E.g. in some games, a player can say "I know why the King has red hair - although most in his family line are brown or blond-maned, the legend says that once every five or ten generations one will be born with red hair, and he or she will prevail in every battle they fight, for they are blessed by Firey Yorse" and then the GM doesn't get to say no to that, it's now part of the setting. The player may or may not need to spend a resource to get to make such a declaration.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 7, 2024 18:37 |

|

Glazius posted:You've got my definition mostly solid, but I can see you're still having trouble applying it. The concept of "parts of the gameplay that don't interact with anything" might help? I mean, it seems like the entire dividing line between Plot and Prop under your model is that Prop has explicit ways it expects to be interacted with (game mechanics) and Plot doesn't. Like, definitionally, the whole point of Plot is that it's stuff that has meaning/interactivity that's entirely dictated by what the group accepts as narratively appropriate (traditionally handled by GM common-sense rulings). Maybe there isn't a Chekov's Gun-style preplanned plot (lower-case p 'plot') that it slots into, but a huge part of what makes RPGs fun is that as soon as a fact about the game world gets introduced, it's up for anyone to play off of and build on top of. If the players can think of a way to use that fact, they can--even if the GM never considered it before. I'd say it even goes further than that, though. Even if the fact never gets used, it fleshes out the game and changes how the players relate to/visualize the character, which absolutely then flows out to impact how play resolves. I'd even go so far as to say that there are RPGs like Warhammer or WOD where the art in the rulebooks are almost more influential in shaping how people play than the game's mechanics--even if a Plot element is ephemeral, in a very real way those mental images formed are what RPG gameplay *is*. Trying to claim that Plot in some way doesn't matter or is only decoration or has less weight than Prop feels like an intellectual dead-end. It also feels like your 'everyone knows equally' bit might be a bit of a distraction--that feels like more of a quality that Prop tends to have than a core definitional requirement. It's real easy to imagine weird edge cases where definitions break down, otherwise. Like, D&D skill checks are kind of weird in this format. When to use a skill check is a common-sense call by the GM, which skills to use is a common-sense call by the GM, what the DC should be is a common-sense call by the GM (with some examples/guidance given by the book that absolutely do not cover all situations), and the effect of passing or failing one is entirely up to a common-sense call by the GM. Are skill checks mostly within the realm of Plot and not Prop? The only part of them that has that sort of 'objective' equally-knowable quality is that you roll a die and add the bonuses from the part of the character sheet your GM chose for you I'd even say that the definition I gave in my last post is a little too restrictive--it doesn't really have a good grasp on how to handle mechanical rulings; situations where the GM either improvises a mechanic or has their own little subsystem they use to handle certain situations that fall outside of the book rules. Like, if the GM makes a call for a player on the run from the mob that "every day roll a d6--if you roll a 1 the loan shark has found where you're staying"--that leaves the same kind of integer-like data-facts that Props have and has the same hard-coded interaction-behaviors, but falls outside of that equally-knowable/social contract set of boundaries. I think that your 'equally knowable' dynamic is describing something real and interesting in RPGs, but something that's distinct from the other stuff you're describing. Under a model where there's a Plot and a Prop layer, and what makes RPGs unique lives in how the two bounce off each other, I think that the inability to fold moments like I just described into the 'Prop' side of things shows that your current set of descriptions are still a little too small and rigid Leperflesh posted:Is it important, or not important, for the sake of your analogy, that in many games the GM is not the sole arbiter of what it means that the king has red hair? Including sometimes players having full power to decide (ad-hoc or otherwise), individually or collectively, what an otherwise still undetermined setting or plot detail will be, without the GM having veto power? I think this also points to the issue that Plot and Prop can pretty easily transform into each other/a fact can exist in both layers at once. In a game where you can take a common-language trait and give it mechanical weight, what's Plot and what's Prop can shift mid-play as resources get spent and character sheets evolve OtspIII fucked around with this message at 02:14 on Jun 10, 2021 |

|

|

|

Leperflesh posted:Is it important, or not important, for the sake of your analogy, that in many games the GM is not the sole arbiter of what it means that the king has red hair? Including sometimes players having full power to decide (ad-hoc or otherwise), individually or collectively, what an otherwise still undetermined setting or plot detail will be, without the GM having veto power? Yes, I'm assuming we're talking about a D&D-style game here where the GM has most of the power over the world plot. Other games assign responsibility for plot to players in different ways. OtspIII posted:Like, D&D skill checks are kind of weird in this format. When to use a skill check is a common-sense call by the GM, which skills to use is a common-sense call by the GM, what the DC should be is a common-sense call by the GM (with some examples/guidance given by the book that absolutely do not cover all situations), and the effect of passing or failing one is entirely up to a common-sense call by the GM. Are skill checks mostly within the realm of Plot and not Prop? The only part of them that has that sort of 'objective' equally-knowable quality is that you roll a die and add the bonuses from the part of the character sheet your GM chose for you Let me diagram this real quick then. You want to climb down the mossy cliff behind a waterfall (plot) so the GM thinks about the difficulty (plot -> prop) and says "sure, make a DC 18 Str(Athletics) check". You roll, add, and get a 20 (prop). The skill check passes (prop -> plot), and you climb down the cliff successfully (plot). The GM knows you're being hunted by the mob (plot) so they think about the mechanics for that (plot -> prop) and say "roll a d6. Don't roll a 1, or they found you". You roll a 4 (prop). It wasn't a 1 (prop -> plot), so the mob doesn't find you today (plot). It all seems pretty clear to me. Glazius fucked around with this message at 20:53 on Jun 10, 2021 |

|

|

|

Glazius posted:Yes, I'm assuming we're talking about a D&D-style game here where the GM has most of the power over the world plot. Other games assign responsibility for plot to players in different ways. This reminds me of an interesting genre that's relevant to this discussion. How familiar are you with Free Kriegsspiel (sometimes abbreviated FK or FKR)? It's a movement playing games that do have mechanics, but very explicitly don't have any Prop. It's one of those things that on the edge of being a RPG/not being one, but the actual moment to moment gameplay is still extremely RPG-like Glazius posted:Let me diagram this real quick then. I think I have a decent grasp of both the definitions you're giving to Plot/Prop at this point, and also on the parts of play you want each to map onto (like with these diagrams), but my confusion is more on how the former actually creates the latter. I think your mapping of how a skill check works makes sense. You're making a distinction between parts of the game that have preset methods for how they should be resolved (Prop) and parts of the game that are resolved by an impromptu ruling (Plot). Importantly, (and correct me if I'm wrong) that preset method has to be able to function without a freeform judgement call, right? Like, it has to be sort of mechanical and almost automatic. The reason this is an important distinction to make is that otherwise everything in the game would be Prop--after all, there is a preset way to interact with all the Plot-ish parts of the game--a GM/communal judgement call. The part that's a little tricky is in when the two intersect--the DC of a climb is something that gets determined completely by judgement call, but then gets used for a plot->plot interaction (rolling your skill value against it). What you say above makes sense, though--that's just the spot where Plot gets translated into Prop. It doesn't matter that the process by which the DC gets determined isn't something preset or knowable to all, because this process happens before we actually get to the Prop level. So far so good Glazius posted:The GM knows you're being hunted by the mob (plot) This is where things break down a little, though. Under the definition laid out before, a big part of Prop is that it's something everyone agreed to before play--possibly just by going "okay, yeah, we'll use the rules from this book". The diagram above mostly fits the model we've been talking about, but fails on the level of being something that everyone pre-agreed to and can understand equally--it's a mechanic the GM invented to fit the moment. Does it still count as Prop under this model because, even if the mechanic wasn't something everyone was capable of understanding when play began, once it has been invented it becomes something that all players can understand equally? What if instead of asking the player to make the roll, the GM just makes them roll without explaining what it means. What if they make the roll themselves, in secret? You'd still have all the mechanical trappings, but would lack the "everyone can know it, if they ask" side of things. Or is it not that people have access to it/know that the mechanic is being used that's important, and instead the dividing line is that the process used for resolution is something that could be expressed as a formula with no judgement-call interpretations involved? Like, when you say that it's knowable-to-all, do you mean that it's just something that *could* be expressed as a "means the same thing to everyone", not that everyone needs to have access to it (or even have access to the knowledge that it's being used)? To be clear, there are really just two big sticking points I have with this theory at this point: 1) Rules are fluid and can change or be used/modded/skipped over fluidly in-play, which complicates the idea that the rules being used can be knowable to all. If this theory's answer to this is that this is fine, and that as long as the process behind any given ruling can be knowable at the time/after it's used it still qualifies as a Prop (even if this was the first time some of the players ever had access to knowing about the mechanic, and even if it never gets used again), then I don't have any issue with it. 2) Claiming that a mechanic has to be non-secret to be a Prop feels arbitrary and exclusive to me. If, instead, you just mean that a resolution has to rely entirely on mechanical processes (that could be summed up as an objectively-interpretable set of rules, involving no subjective interpretations), then I'm on board with you.

|

|

|

|

OtspIII posted:This reminds me of an interesting genre that's relevant to this discussion. How familiar are you with Free Kriegsspiel (sometimes abbreviated FK or FKR)? It's a movement playing games that do have mechanics, but very explicitly don't have any Prop. It's one of those things that on the edge of being a RPG/not being one, but the actual moment to moment gameplay is still extremely RPG-like Yeah, one of the common functions of Prop elements is to disclaim decision-making onto them. Usually in concert with some kind of randomizer, rather than letting some kind of state machine tick over. FK sounds more or less like the original Kriegspiel, with an experienced referee making calls on how well military maneuvers would work. quote:The part that's a little tricky is in when the two intersect--the DC of a climb is something that gets determined completely by judgement call, but then gets used for a plot->plot interaction (rolling your skill value against it). What you say above makes sense, though--that's just the spot where Plot gets translated into Prop. It doesn't matter that the process by which the DC gets determined isn't something preset or knowable to all, because this process happens before we actually get to the Prop level. So far so good A random prompter the GM uses in secret might not even be part of the game, actually. If it's not available to the other players, it's not that much different from the GM making decisions on their own. It's also probably a bad idea to keep it secret if they intend to reuse it, because if it were done openly it would absolutely be a prop and maybe the other players have something to say about those odds? Heck, maybe there's some game mechanic the GM is forgetting about that might be a better fit. If it comes out into the open, the GM can also start making plot -> prop connections to modify it - as the other players propose actions, the GM can say "if you do that, it makes it more/less likely for the mob to find you". ("Less likely" at a 1 might mean rolling a "find save" on another d6 and getting at least a 6/5/4/3/2, or stepping the d6 up to a d8/d10/d12.) quote:To be clear, there are really just two big sticking points I have with this theory at this point: Yes, the relevant distinction is that the prop is knowable at the time it's used. In a lot of games, don't the rules give the GM the power to make new rules for situations the existing rules don't cover? The rules-as-played for a game that does that could never be fully known in advance, because new rules can be created to suit the moment. I think it's the combination of a novel mechanic done in secret that's the tipping point here. A non-novel mechanic done in secret is, for example, the GM's monsters moving tactically through darkness. The PCs can't see them move, but they still follow the known movement rules. Doing a novel mechanic in secret is the GM disclaiming decision-making onto something only the GM knows about, which, to say again, is not much different from the GM making decisions on their own.

|

|

|

|

Glazius posted:A random prompter the GM uses in secret might not even be part of the game, actually. If it's not available to the other players, it's not that much different from the GM making decisions on their own. I mean, anything that's involved in the process of resolving how the narrative plays out is part of the game. And while it's the same as an arbitrary decision from a player-facing perspective, I think it still fits the "cede limited agency over how the narrative goes to a computational mechanic" side of things, and changes the mood of how things plays out. If nothing else, it creates a story where taking risks results in things going wrong randomly, as opposed to when the GM decides they feel like throwing some hardship at the players. Like, adding the whole layer of requirements related to things being known does two things: it makes the theory more complex, and it creates weird cases where things that look way more like Props than Plot end up getting thrown in the Plot category. Glazius posted:It's also probably a bad idea to keep it secret if they intend to reuse it, because if it were done openly it would absolutely be a prop and maybe the other players have something to say about those odds? Heck, maybe there's some game mechanic the GM is forgetting about that might be a better fit. It being a good or bad idea isn't really relevant to the theory, but I don't understand why it being out in the open is necessary for it to be interactive. If the Plot fact that "the mob is after you" is known to the player, they don't need to know that there's a hidden mechanic to be able to influence it; they can just take Plot actions to hide, and that can just alter the odds of the hidden roll. Exposing the exact mechanics of things like this or not is more of a stylistic thing than anything else--it doesn't really affect the player's ability to understand or influence the situation. It just feels to me like if the only thing dividing it between "Prop" and "not a part of the game at all" is whether any player sneaks a peek over the GM screen and catches a view of the GM's notes, you're wandering away from useful distinctions. Glazius posted:Yes, the relevant distinction is that the prop is knowable at the time it's used. In a lot of games, don't the rules give the GM the power to make new rules for situations the existing rules don't cover? The rules-as-played for a game that does that could never be fully known in advance, because new rules can be created to suit the moment. I mean, that's also not really a rule the book has the power to grant/take away from a group. That's also not really a Prop-layer rule, anyway, under how we've been talking about things so far--it's entirely judgement calls, no formal system

|

|

|

|

Glazius posted:I think it's the combination of a novel mechanic done in secret that's the tipping point here. A non-novel mechanic done in secret is, for example, the GM's monsters moving tactically through darkness. The PCs can't see them move, but they still follow the known movement rules. Doing a novel mechanic in secret is the GM disclaiming decision-making onto something only the GM knows about, which, to say again, is not much different from the GM making decisions on their own. By this conception, if I play a game of solitare and nobody's around, the cards aren't props, because I can cheat and nobody will know but me. How can the player's knowledge of game mechanics matter? If players literally don't know the game, everything that used to be props are now plot? More broadly, this all feels suspiciously D&D-centric, and additionally discounts the fact that the GM is also a player, and is also playing a game. What's a prop for the GM and what's a prop for the other players should be the same.

|

|

|

|

Leperflesh posted:More broadly, this all feels suspiciously D&D-centric, and additionally discounts the fact that the GM is also a player, and is also playing a game. What's a prop for the GM and what's a prop for the other players should be the same. no. NO! if the players touch my GM mask they will steal its powers and ruin it. It must be kept safe and unsullied by their filth.

|

|

|

|

Leperflesh posted:By this conception, if I play a game of solitare and nobody's around, the cards aren't props, because I can cheat and nobody will know but me. How can the player's knowledge of game mechanics matter? If players literally don't know the game, everything that used to be props are now plot? I'm being D&D-centric because it's probably the most imbalanced distribution of plot responsibility out there. Many other games spread a lot more plot-determining power around, but in most cases they still just make one person responsible for any plot element, just not the same person. Fewer games spread any kind of prop-determining power around, in the sense of improvising new rules as needed, and there are some "GM-less" games which are usually played by a fixed ruleset with little to no room for improvising. But that aside, that's an interesting couple of examples you picked. The only thing that makes for a game of solitaire is your own discipline in holding yourself to the rules. If you play a game of solitaire and you cheat, you're not playing solitaire anymore. You're performing a card-stacking activity which occasionally bears some resemblance to the rules of solitaire, and the cards are just decoration, not props. As an aside, I say "just decoration", but decoration isn't irrelevant. Decoration can contribute greatly to the appeal and feel of a game in play. It can make it easier to improvise new plot developments, and it can make it easier to manage props by making them more relatable than cold equations. The only reason I say "just decoration" is that decorative elements do not participate in the "is this an RPG or not" logic of plot and prop interrelating. If you play one of the many intellectually propertied versions of Monopoly and appreciate the atmosphere, that doesn't suddenly make it an RPG. If players don't know and aren't allowed to learn the game, then from their perspective all the props are decoration, because they have no idea how to engage with them. They engage the game only on a plot level, as if it were pure Kriegspiel - they say what makes sense to them to accomplish their character goals, and then there's some rattling around before judgement is passed. It's the same way with a die with secret mechanics that the GM rolls in secret, really. The player has no idea how to engage with it except with on a plot level. What more is "the same way" in both of those scenarios is that there's a complicating factor to their play that the player doesn't know about. They're not actually appealing purely on a plot dimension, there's the distortion that the hidden mechanics are applying to their choices. They might be better off or worse off by making certain choices and not know it. And that feels a lot like they're being cheated. Glazius fucked around with this message at 01:22 on Jun 13, 2021 |

|

|

|

DalaranJ posted:So, I read Jon Peterson's new book The Elusive Shift and I wanted to discuss a part of it, and I think this is the place. Fortunately, I can constrain the discussion pretty well, thanks to Jon Peterson's blog. Iíve been been doing a lot of thinking about this stuff lately and I donít understand why people try to bucket into 4-6 archetypes and then turn around and say most people are two or three of them. Starting at the ď8 Kinds of FunĒ and going from there (although that is missing Power, Progression, and Application of Ability - I found a list of 14 things that I agreed with more) seems like an easier way to parse what people want out of a game. If everyone likes aesthetics, have maps, dice, books, handouts, etc. If they want immersion, keep meta talk to a minimum. If theyíre narrative focused, donít do a meat grinder dungeon. But most things I see talk about player types or traits that you then have to translate into information about how people have fun. Am I missing something?

|

|

|

|

Adding references: 8 Kinds of Fun: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marc_LeBlanc 14 Kinds of Fun: https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/227531/fourteen_forms_of_fun.php Player Types and Traits: https://critical-hits.com/blog/2008/01/23/robins-laws-revisited-part-2-player-types-and-traits/ A thorough review and discussion of this stuff: https://www.runagame.net/2015/06/player-types-and-motivations.html?m=1 (and is it an inside joke to call Matt Colville Matt Campbell ITT?)

|

|

|

|

I am pretty firmly of the mind that the chart is another analysis tool that assumes a really specific, mostly D&D frame of reference. Plenty of neat indie games marry mechanics and roleplaying, and design systems where trying to do well mechanically encourages rather than restricts story-telling.

|

|

|

|

Glazius posted:I'm being D&D-centric because it's probably the most imbalanced distribution of plot responsibility out there. Many other games spread a lot more plot-determining power around, but in most cases they still just make one person responsible for any plot element, just not the same person. Fewer games spread any kind of prop-determining power around, in the sense of improvising new rules as needed, and there are some "GM-less" games which are usually played by a fixed ruleset with little to no room for improvising. It's interesting to see a third element introduced, decoration. And, while I am pretty sure I understand your explanations, which I thank you for the great deal of effort you've put into providing, I'm also convinced that this isn't going to be a useful way to discuss games, at least for me. I can't point to game elements and categorize them without also specifying that specific players (one, several, or all) at the table do or don't understand or believe they understand correctly or haven't learned yet, what it is on a rules vs. known-facts vs. decorative chart. How can I say "this part of this game's plot/prop exchange has x, y, and z attributes" if the nature of that element is different when Bobby temporarily brain-farts and forgets the rule? I would like tools for discussing RPGs that feel more firm. "These are rules mechanics" and "these are setting facts" and "these are areas where improvisation of (rules or facts) are permitted or encouraged" and "this part remains unexamined for the purposes of maintaining willing suspension of disbelief" and so forth feel like to me, the language that can usefully allow us to compare and contrast different games, playstyles, and design goals. Anyway that may just be me and I wouldn't want to discourage anyone else from using the plot/prop language if they find it useful. Thanks again.

|

|

|

|

DrOgreface posted:Iíve been been doing a lot of thinking about this stuff lately and I donít understand why people try to bucket into 4-6 archetypes and then turn around and say most people are two or three of them. Starting at the ď8 Kinds of FunĒ and going from there (although that is missing Power, Progression, and Application of Ability - I found a list of 14 things that I agreed with more) seems like an easier way to parse what people want out of a game. If everyone likes aesthetics, have maps, dice, books, handouts, etc. If they want immersion, keep meta talk to a minimum. If theyíre narrative focused, donít do a meat grinder dungeon. But most things I see talk about player types or traits that you then have to translate into information about how people have fun. Am I missing something? I don't really think of the "8 Kinds of Fun" model works very well when applied to player preferences--what I think's really cool about it is the idea that any of the 8 kinds of fun are fun, and pretty much every player gets enjoyment from all 8 kinds to some degree. I feel like as soon as you start using it as an identifier ("I like Challenge! My players like Aesthetics!"), it actually sort of flattens over or distracts from thinking about taste in a more relevant way--whether you like a thing or not is going to be way more about the specifics of how it provides fun than the broad genres of fun it's providing. To come at it from a slightly video-game direction, how much you like a high-challenge game is going to be way more about whether it's a fast and twitchy (FPS), slow-burning strategic (Turn Based Strategy), information and input overload (RTS), risk mitigating luck-pushing (Gambling), steady progression (RPG), or high-stakes punishing (Roguelike) type of challenge. Pretty much everyone's capable of feeling good when they do an uncertain thing and come out on top, but different people have different tolerances and prefer different forms of challenge. The 8 Kinds of Fun model is useful way more as a "am I neglecting some kind of fun in my game that I could otherwise be providing" diagnostic than a "what kind of game am I making" one. Also, not to defend it too hard (I think it's way more useful for the general idea behind it than its details), but I'd say it actually classifies Power, Progression, and Application of Ability pretty clearly. Power lines up pretty well as a sub-category of Fantasy, Progression with Discovery (and slightly with Submission), and AoA with Challenge (and a bit of Expression).

|

|

|

|

Ash Rose posted:I am pretty firmly of the mind that the chart is another analysis tool that assumes a really specific, mostly D&D frame of reference. Plenty of neat indie games marry mechanics and roleplaying, and design systems where trying to do well mechanically encourages rather than restricts story-telling. Yeah, I donít like the charts at all because the axes make things either/or that arenít exclusive. OtspIII posted:To come at it from a slightly video-game direction, how much you like a high-challenge game is going to be way more about whether it's a fast and twitchy (FPS), slow-burning strategic (Turn Based Strategy), information and input overload (RTS), risk mitigating luck-pushing (Gambling), steady progression (RPG), or high-stakes punishing (Roguelike) type of challenge. Pretty much everyone's capable of feeling good when they do an uncertain thing and come out on top, but different people have different tolerances and prefer different forms of challenge. The 8 Kinds of Fun model is useful way more as a "am I neglecting some kind of fun in my game that I could otherwise be providing" diagnostic than a "what kind of game am I making" one. For your Challenge examples, people can like any of those things without it being a challenge too. I think itís useful to consider them separately. For the 8 kinds of fun, Fantasy was more specifically Escapism, not a Power Fantasy, Discovery is World Exploration (not loot, level ups, achievements, filling out a collection). I also think AoA is distinct from challenge. For example, when people talk about System Mastery - I have a friend who loved to DM 3.5e, in my opinion, partly because they knew the rules backwards and forwards and could adjudicate any questions very promptly. I also like to shoot hoops in an empty gym. I donít think those situations are challenging, but it is satisfying to demonstrate skill in something. I donít think people should try to identify with a particular kind of fun, but as a DM it is useful to me to say my players want Progression and Narrative, and donít care much for Discovery or Aesthetics, and thereís a guy who really likes Immersion, so keep that in mind. That seems more actionable than I have a Butt Kicker/Instigator, a Story Teller/Tactician, a Watcher and a Tactician/Power Gamer

|

|

|

|

DrOgreface posted:For the 8 kinds of fun, Fantasy was more specifically Escapism, not a Power Fantasy, Discovery is World Exploration (not loot, level ups, achievements, filling out a collection). I don't think that's correct These categories are broad--real broad. Fantasy is any kind of pretending to be someone you're not. Discovery is described as being about uncharted territory, but it doesn't need to be limited to 'physical' territory--it can be just as much about the joy of learning rules systems or getting to see all the unlockable art cards as it is about going over a hill and seeing what's on the other side. I mean, the card unlock is also a fun Challenge (because it marks the completion of a task) and a fun Sensation (because the card looks nice), but the whole idea here is that these pleasures are all happening all the time. There's no GNS-style "you only experience one fun at a time" dynamic here. DrOgreface posted:I also think AoA is distinct from challenge. For example, when people talk about System Mastery - I have a friend who loved to DM 3.5e, in my opinion, partly because they knew the rules backwards and forwards and could adjudicate any questions very promptly. I also like to shoot hoops in an empty gym. I donít think those situations are challenging, but it is satisfying to demonstrate skill in something. I donít think people should try to identify with a particular kind of fun, but as a DM it is useful to me to say my players want Progression and Narrative, and donít care much for Discovery or Aesthetics, and thereís a guy who really likes Immersion, so keep that in mind. That seems more actionable than I have a Butt Kicker/Instigator, a Story Teller/Tactician, a Watcher and a Tactician/Power Gamer I don't really understand how shooting hoops in an empty gym isn't a challenge. Challenge doesn't mean "hard", it means overcoming an obstacle (Game as obstacle course). It definitely doesn't require an opposing team, or no single player game would qualify. Like with my examples of Challenges above, the level of difficulty doesn't matter so much as that there is some pushback. In a twitch game you need good reaction time and coordination. In a strategy game you need to be able to think ahead. In a RTS/MOBA style game you need to be able to parse huge amounts of real time information while holding onto a longer term strategy. In a grinding game you need to have the commitment to pour the requisite time into it. In a gambling game you need to get lucky. In a cinematic horror game you need to be brave enough to walk down the spooky corridor. And so on. You can have an easy FPS, where winning is all but guaranteed, but an easy obstacle is still an obstacle. It may not be to your taste, but a story you find boring is still pretty clearly a Narrative And my point with not liking to use it for players is that it's abstract enough that it makes it real easy to ignore their actual preferences (although it could be used as a way to think through their actual preferences more fully, if used that way). "Likes stories about cosmic horror" seems more actionable than "likes Narrative", and "gets bored when the game spends too long resolving a pure mechanics fight" seems more actionable than "doesn't like Challenge". Designing a game for someone who likes "Discovery" feels like cooking a meal for someone who likes "Protein" OtspIII fucked around with this message at 19:10 on Jun 22, 2021 |

|

|

|

Cool, I think the fact that weíre not in agreement on even what these basic terms mean shows that they arenít some kind of amazingly better way to consider player motivations. Maybe the way that you are interpreting these categories so broadly is hampering their usefulness? I donít consider shooting hoops in an empty gym a challenge because nothing is on the line if the shot goes in or not. Itís like saying flipping a coin is a challenge in and of itself. (If I was trying to hit 10 in a row, or 5 in 10 sec, sure). If someone said they play basketball for the challenge and it turned out they meant they only shoot hoops in an empty gym, it would be confusing. Me doing that I would categorize as Sensory, AoA and Abnegation/Submission (it had a meditative feel to it). Narrative I agree is more useful subdivided by genre (and the 14 kinds of fun did this partially). I guess what Iím thinking is if someone wants Challenge out of an rpg, you canít tell them to roll better than a 1 on a percentile roll and say ďhey, that was an obstacle, way to go!Ē For discovery, I once gave blank outline maps of a continent to players at a session 1, and it turned out none of them really cared about filling that map in with every detail they learned on the adventure. Maybe they liked other kinds of discovery (and we could talk about framing too) but the group did not really care about the Exploration ďpillarĒ. So itís not about whether these terms, defined in a broad sense, exist in a game at all, itís saying hey, if a player has these as their top five things they enjoy, the game needs to have enough of that in it for them to have a good time.

|

|

|

|

DrOgreface posted:Cool, I think the fact that weíre not in agreement on even what these basic terms mean shows that they arenít some kind of amazingly better way to consider player motivations. Maybe the way that you are interpreting these categories so broadly is hampering their usefulness? Oh yeah, I think the whole model is fundamentally more academic than practical. I'd also classify these as academic jargon with fairly specific meaning--I think you're coming at it from a common-language perspective, which is subtly different enough from the initial intent to make discussion get weird easy. I'd for sure say that the model works better when it comes to analysis than production, though--it's not really concerned with quality so much as type. I think you're pretty spot on with all the ways no-stakes hoop-shooting are fun, but I'd say it's still also very much a Challenge on top of those other reasons, in that there's an obstacle that needs to be overcome (physics, your body's coordination), even if there's zero consequence for failure. It isn't really Basketball at that point, and if you aren't setting goals for yourself it's arguably not even a game, but it is still a challenge (if only in a 'I challenge you to do this' way, not a 'it was a challenge but we persevered' way) This does all get a little fussy, though, since there's at least a little of all 8 at play even in the solo hoops example. You can craft a little Narrative about your experience ("I did good today"). There's an expressive layer (refining your personal style of shooting). There's potentially some fellowship, if part of the reason you're doing it is to play with friends. If you imagine that you're scoring the winning shot of a NBA game, there's some fantasy fun. You're discovering something about your body/mental state/etc by doing that sort of focused practice. Some of those are pretty minor (to the point where they might not happen at all, like if you aren't daydreaming at all), but my point is that the thing that's really cool about the theory is more in how it lets you see the many types of simultaneous fun that are happening than in how it prescribes fun. It's less "this is how you should do it" and more "look at all the countless ways you could do it"

|

|

|

|

Leperflesh posted:It's interesting to see a third element introduced, decoration. And, while I am pretty sure I understand your explanations, which I thank you for the great deal of effort you've put into providing, I'm also convinced that this isn't going to be a useful way to discuss games, at least for me. I can't point to game elements and categorize them without also specifying that specific players (one, several, or all) at the table do or don't understand or believe they understand correctly or haven't learned yet, what it is on a rules vs. known-facts vs. decorative chart. How can I say "this part of this game's plot/prop exchange has x, y, and z attributes" if the nature of that element is different when Bobby temporarily brain-farts and forgets the rule? Well, if you're looking at a game as a theoretical exercise, you can probably assume that all your theoretical players aren't going to forget or be ignorant of any part of the game they shouldn't be. Contrarily, if you're analyzing a play session, you can analyze the game objects as they were used by the players at the moment.

|

|

|

|

As far as I can tell player categories were a mis-evolution. They started as categories of experience at the time when RPGs were still being differentiated from wargames. Somehow this was transformed into categorising players by a single experience they enjoy most, and then making a bunch of fallacious assumptions based on that, the most pernicious being that the players' enjoyment will be exactly proportional to the amount of that experience when is included. I love sushi, but I don't categorise myself as a "sushi eater". And it is certainly fallacious that how much I enjoy a meal can be calculated by the amount of sushi it contains. Dumping a load of sushi rice on my pizza will not increase my enjoyment, and I would have quite enjoyed the pizza in the first place. Plus, there's many experience interactions. I met a lady who was introduced to RPGs via a local club who was very much into building stories, but only played games with tactical combat. Not because she was a tactical player, but because she was - by her own description - a visual person, and only games with tactical combat made any effort to provide a visual representation of what the PCs were doing.

|

|

|

|

Yeah, I like puzzles and puzzle games, but puzzles in DND basically never feel right to me

|

|

|

|

Glazius posted:Well, if you're looking at a game as a theoretical exercise, you can probably assume that all your theoretical players aren't going to forget or be ignorant of any part of the game they shouldn't be. I think that if I am looking at a game like checkers as a theoretical exercise, I would assume the players knew the rules perfectly. However, when I look at roleplaying games, I think I would much more safely assume that none of the players know the rules perfectly. I think you're right that for most theoretical discussions assuming everyone is following the rules is a good baseline; although I also find that most RPGs have at least some problems with their rules that are unresolvable - that is, nobody, perhaps even the designer, actually knows the rules perfectly, and that should be taken into account at some point in RPG theory.

|

|

|

|

Is there a good word for concepts within a RPG that are being constantly strived towards but don't actually exist? Ideals? To use a more concrete example, I think the concept of the Shared Imaginary Space is super useful when discussing RPG theory. It's the idea that one of the big goals of play is the construction of this imaginary world, which all the players are then inhabiting together--fairly straightforward, and very useful for discussion. The issue is, though, that it also inherently can not exist--the game lives in the heads of the players, and is going to be subtly different in each player's mind; there is no 'true' version of the game world--it's the product of the players all constantly working to synch up and keep from diverging from each other too much. There is no Shared Imaginary Space that actually exists, but it's sill an extremely important driver of play at the table, since it just functions as a perfect ideal that (even if never truly attainable) gives all players at the table a goal to aim towards. You'll never actually attain it, but by trying to you'll still get better results than if you didn't I think the game's Rules, as being talked about here, works pretty similarly. A theoretical situation where all players know the rules is an ideal to strive towards, and a mutual agreement that the game's rules are equally available and binding to everyone has some stabilizing effects on play, but on some level neither of those concepts actually exist as anything other than abstract ideals. I think there's a lot of interesting stuff to examine about the techniques people use to try to live up to those ideals/smooth things over when actual play fails to do so, and I think it's pretty important that any model of how RPGs work needs to take them into account. The holy grail of the Shared Imaginary Space might not exist, but the techniques and actions people have devised to chase after it definitely do

|

|

|

|

What games actually have good mechanics for action set-pieces that aren't combat? A significant percentage of games have combat as their only complicated subsystem, and some have dedicated rules for vehicle chases/combat. Most everything else is just discrete, single skill rolls. This seems strange considering how much of action/adventure fiction is about other perilous situations--escaping a burning building or a sinking ship, disarming a bomb, whatever. "The hero has to swing on a rope and slide down something" is almost as obligatory as having a fistfight at some point. I'm really only familiar with the concept via games that have a chapter of rules modules for car chases, extended stealth sequences (e.g. "Dramatic Systems" in Vampire and other Storyteller games) and 4e's skill challenges and various attempts to get it right. Of course in the vast majority of games, the GM can just describe perilous circumstances and occasionally demand skill rolls. But then it's on them to have a fail-forward solution in place for everything, and be sure that they're not just rolling dice until the PCs fail. OtspIII posted:Is there a good word for concepts within a RPG that are being constantly strived towards but don't actually exist? Ideals?

|

|

|

|

Halloween Jack posted:What games actually have good mechanics for action set-pieces that aren't combat? I really like CoC 7E's chase rules. You determine the relative movement rates of the groups involved in the chase and then set up a track with nodes along which both groups have to move. Certain nodes can have skill checks associated with them that can force a group to stop or give them the opportunity to speed themselves up or slow their opponents down. If the fleeing group gets to the end of the track before the pursuing group catches them, they escape. If not, the appropriate encounter happens.

|

|

|

|

The inevitable problem with those systems is that they think they can improve mechanics by simply adding some rules, when what's actually missing is a model sophisticated enough to interact with in different terms. Plenty of games have chase rules, but they inevitably come down to "roll to go fast, and if there is a roll to overcome an obstacle, make that roll". Likewise, "skill challenge" systems that are simply based on total numbers of successes tend to just be "roll the success over and over again". It happens because combat had an entire genre of tabletop games devoted to it which developed models which were sophisticated enough to have choices yet easy enough to be understandable, and were fun to interact with; and there were enough of them to develop standard patterns. Because there has never been a genre of tabletop chase or stealth games, there's no such reference existing, and they can't be bothered or afford to work on one from scratch; so they try to do without it and inevitably it doesn't work.

|

|

|

|

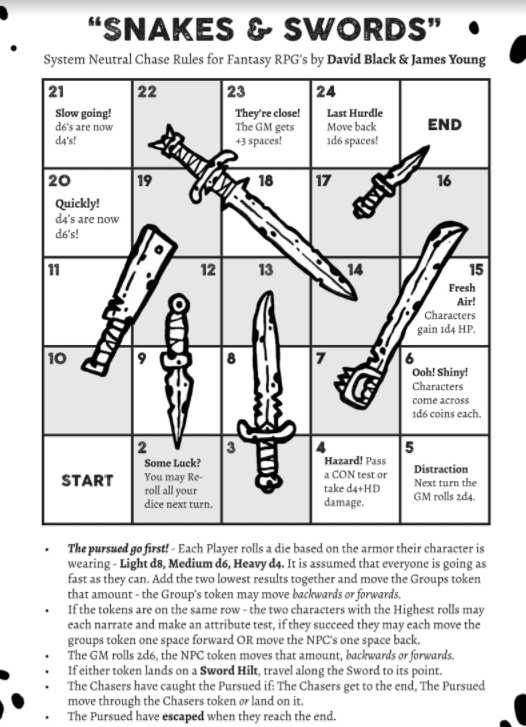

hyphz posted:The inevitable problem with those systems is that they think they can improve mechanics by simply adding some rules, when what's actually missing is a model sophisticated enough to interact with in different terms. Plenty of games have chase rules, but they inevitably come down to "roll to go fast, and if there is a roll to overcome an obstacle, make that roll". Likewise, "skill challenge" systems that are simply based on total numbers of successes tend to just be "roll the success over and over again". I thought the Snakes & Ladders-inspired chase rules were a nice concept  And Dael Kingsmill created an interesting hunting framework for her Displacer Beast reimagining episode back in April: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aV1-VNRqTtA

|

|

|

|

Halloween Jack posted:What games actually have good mechanics for action set-pieces that aren't combat? A significant percentage of games have combat as their only complicated subsystem, and some have dedicated rules for vehicle chases/combat. Most everything else is just discrete, single skill rolls. This seems strange considering how much of action/adventure fiction is about other perilous situations--escaping a burning building or a sinking ship, disarming a bomb, whatever. "The hero has to swing on a rope and slide down something" is almost as obligatory as having a fistfight at some point. The closest thing I think I've seen (but haven't actually experienced in play) is the concept of Victory Points in Pathfinder 2e. It really does feel like a big vacuum. Oh! And anything from the Burning Wheel line has pretty in depth rules for a bunch of non-combat situations (using a system that's identical to their combat system). I've been working on a negotiation subsystem meant to work sort of like you're talking about, so I've been thinking about what qualities a system like you're describing would even need/what it is that makes combat have so much gravity in RPGs. I think there are a few things a set-piece resolution system would need to feel as good as combat typically can. It would need to. . . Resolve over time -- you said this; part of why combat feels significant is because it takes a long time to resolve. I don't think this is sufficient to make it interesting, but it is required for some of the other stuff. Also, there is some inherent value in being able to see a win/lose coming into focus over time Have a clear default action -- there's a really clear default action you can take if you don't know what else to do in combat: just attack an enemy. The win state is clear (get their HP down), and you have a nearly universally available tool for accomplishing that Create dynamic tactical situations -- combat has enough going on that it's really hard to fully 'understand' it. Characters have many different actions they can take each turn, everyone has a physical position that dictates who they can reach or not, etc. Also, really importantly, it can tie into the fiction pretty easily. The players can improvise actions that aren't on their character sheets, they can leverage how the fight is going to start a negotiation, or run away, or whatever. Create dynamic threats -- each turn of combat is almost like a little puzzle, where there's a set of little crises you need to avert. Maybe you're winning the fight overall, but the wizard's at 1hp with two goblins surrounding them. How do you get them to safety in time? This is one of the big advantages of resolving over time; each turn just organically creates new little sub-challenges that need to be resolved. Allow the players to spend limited resources to deal with threats -- characters have abilities and consumables that they can expend to deal with a situation, but using them up means you might not have them when you need them later. Does the wizard use their final spell slot to teleport away, or do they take a risk and hope their teammates can deal with the situation in time? Does the fighter forgoe their attack for the round in order to throw the wizard over their shoulder and run? Allow for unexpected consequences -- combat can lead to all sorts of unexpected events. You're trying to scare the goblins away, but now your wizard is dead. You repelled the pirates, but now your boat is sinking. You fought against the medusa, and now you need to find a scroll of stone to flesh. And yeah, as hyphz said, I think most systems I've seen that try to create "social combat" or something like that basically just turn it into a largely non-interactive dice race. "Roll three successes out of five tries" isn't that different than a normal skill check, because it doesn't give the players a chance to reassess their strategy and try a different approach/break out the limited use resources/cut their losses and run/etc. It's tough, though, since a lot of these systems are aiming to be situation-agnostic; it's hard to design a system that allows for a dynamic environment when you're trying to simulate both verbal arguments and car chases. Halloween Jack posted:Fruitful void? I think this is related and has some good overlap, but isn't quite the same time. Fruitful Void is more of a "some things would be made way less interesting by making them quantifiable via mechanics, so you have to point at them indirectly", while this is more "using abstractions leads to better results, but also needs mechanisms for righting things when reality desyncs from theory" OtspIII fucked around with this message at 23:19 on Jun 27, 2021 |

|

|

|

Carrying this over from the industry thread:KingKalamari posted:This is a good explanation and I think helps me to pin down the sort of philosophical x factor I've been trying to articulate: What I've been trying to define as a design philosophy is really more a case of designers losing the thread of design philosophy. I'm not sure I agree with this. It was codified pretty early on that the basic orc was more difficult than the basic goblin, but at least since BECMI, it was also codified that there are individual goblins who are more powerful than the basic orc and so on. I don't see that as being any different than a first level human fighter is no match for an ogre, but an ogre is no match for a tenth level human fighter. To your further point, "an overabundance of goblinoid subspecies" is entirely subjective. So is any dissatisfaction with invented kinds of armor. These strike me as being unrelated aside from both being examples of how D&D makes in-fiction things mechanically discreet, and your issues with them strike me as being a bit contradictory, like there is not enough mechanical discretion between made up goblins and orcs, but there is too much mechanical discretion for a made up kind of armor. And I think it's a bit of a stretch to say this is the root of grognard complaints about non-magical healing. I think that's just deliberately ignoring what every previous edition has said about HP and what they represent to make up another reason to hate on 4E. I don't mean to be dismissive, but this philosophical X factor you're identifying strikes me as just a function of mechanically codifying elements of the game's fictional world to make it a playable game. Certainly, there's an issue among developers and players where they confuse game mechanics with fictional laws of the universe, but that isn't a problem exclusive to D&D. Like from the perspective that mechanics codify the fiction, yeah, it's an immutable law that the average orc is more threatening than the average goblin, but it's also an immutable law that Brujah get powers that Ventrue don't or that a blaster rifle does 1D more damage than a blaster pistol.

|

|

|

|

PeterWeller posted:Carrying this over from the industry thread: Alright, I have a response to this I'm in the process of drafting up, however I've over the course of the day realized I'm completely exhausted due to some RL stuff which probably hasn't done any favors to my attempts to coherently explain the concepts I've been talking about. I really want to continue this discussion as I think it's very interesting but I probably won't have a coherent response up for a day or two.

|

|

|

|

This really shows the silliness of the attitude. Snakes and Ladders isn't a good board game as anything but a time-killer for children, so why on earth would any designer (let alone the author of the Black Hack) think it would be a good RPG mechanic?

|

|

|

|

hyphz posted:This really shows the silliness of the attitude. Snakes and Ladders isn't a good board game as anything but a time-killer for children, so why on earth would any designer (let alone the author of the Black Hack) think it would be a good RPG mechanic? It's specifically for chase scenes, which is the one thing snakes and ladders represents well! Especially because it's the PCs versus the DM's monsters, not the PCs fighting each other (at least, as long as one doesn't try to outrun you so the dragon eats you first). It's originally by James Young and after he played it a bunch and it actually worked out well, then David Black did the fancier laid out slightly revised version. It's good! You should try it!

|

|

|

|

Arivia posted:It's specifically for chase scenes, which is the one thing snakes and ladders represents well! Especially because it's the PCs versus the DM's monsters, not the PCs fighting each other (at least, as long as one doesn't try to outrun you so the dragon eats you first). It's originally by James Young and after he played it a bunch and it actually worked out well, then David Black did the fancier laid out slightly revised version. It's good! You should try it! It could work well, I suppose, if the knowledge that it's completely random doesn't bleed into the fiction and ruin it for everyone involved. But for many folks it does.

|

|

|

|

hyphz posted:This really shows the silliness of the attitude. Snakes and Ladders isn't a good board game as anything but a time-killer for children, so why on earth would any designer (let alone the author of the Black Hack) think it would be a good RPG mechanic? I think how much I like this subsystem is entirely based on how flexibly it's run. It seems like it might be fine if you treat it as "this is what happens by default, but clever player plans can break the default rules", but I think I'd find it pretty frustrating if it was run straight. I'd also almost definitely replace most of the tile events with hooks for slightly less abstract situations--"your bag catches on a rock, choose between tearing it open and losing half the items in it or losing your movement for the turn" is a lot more interesting than "take some unpreventable damage" or "use different dice for a while". If you can circumvent the choice by, like, casting Floating Disc under your bag to catch all the stuff that falls out then that's even better. PeterWeller posted:To your further point, "an overabundance of goblinoid subspecies" is entirely subjective. So is any dissatisfaction with invented kinds of armor. These strike me as being unrelated aside from both being examples of how D&D makes in-fiction things mechanically discreet, and your issues with them strike me as being a bit contradictory, like there is not enough mechanical discretion between made up goblins and orcs, but there is too much mechanical discretion for a made up kind of armor. And I think it's a bit of a stretch to say this is the root of grognard complaints about non-magical healing. I think that's just deliberately ignoring what every previous edition has said about HP and what they represent to make up another reason to hate on 4E. The twenty types of goblins problem does seem pretty silly on its face, but I think it's actually a pretty decent way to handle things (especially if core rulebook is fairly tight and only has one or two of them). As a fairly experienced GM, I'm way more likely to have a homebrew setting full of homebrew monster types than to use any of the "goblins but there's a lot of them" or "goblins but they can jump" or whatever from the books, but that doesn't mean I'm not getting anything out of those monsters. To some extent, every monster is providing three big things--a set of stats/abilities, a set of motivations/behaviors, and a basic concept. Even if I'm homebrewing monsters, these examples are useful to me as inspiration/examples. I may never run that Fiend Folio frog with paralyzing hi-beam eyes or whatever, but maybe I'll steal his gaze mechanics. Goblins and Kobolds may be pretty similar mechanically, but having one example monster that's a self-destructive miscreant and another that's a cowardly dragon-worshipper is still an interesting difference. If you take all the goblin subspecies as examples and inspiration rather than a list you can't deviate from, they work pretty well You totally could reduce a lot of them to, like, a one sentence idea you could then apply to the default goblin stat-block. These humanoids look like frogs. Take a goblin and give it a 30' jump ability / These ones have color-changing skin. Take a goblin and give it advantage on stealth checks / These ones worship dragons. Give them a dragon that they worship. / etc. I don't think you actually gain that much from this approach, though, and you are adding one more layer of moving parts for people learning to GM the game to deal with. Also, if you make it too much a list of templates rather than a list of theoretical species, you lose a lot of the charm of trying to imagine a world in which all these creatures live, which I think is a big part of the draw for the "I collect RPGs books to read but barely use any but 3-4 core ones in actual play" crowd.

|

|

|

|

Halloween Jack posted:What games actually have good mechanics for action set-pieces that aren't combat? A significant percentage of games have combat as their only complicated subsystem, and some have dedicated rules for vehicle chases/combat. Most everything else is just discrete, single skill rolls. This seems strange considering how much of action/adventure fiction is about other perilous situations--escaping a burning building or a sinking ship, disarming a bomb, whatever. "The hero has to swing on a rope and slide down something" is almost as obligatory as having a fistfight at some point. Victory Gamesí James Bond 007 has a highly acclaimed system for chases, which is based on bids to increase the difficulty of rolls both sides need to improve their position and avoid injury and to take the initiative, each turn.

|

|

|

|

KingKalamari posted:Alright, I have a response to this I'm in the process of drafting up, however I've over the course of the day realized I'm completely exhausted due to some RL stuff which probably hasn't done any favors to my attempts to coherently explain the concepts I've been talking about. I really want to continue this discussion as I think it's very interesting but I probably won't have a coherent response up for a day or two. Cool! No worries. I look forward to your reply. I hope I'm not coming across as dismissive. OtspIII posted:The twenty types of goblins problem does seem pretty silly on its face, but I think it's actually a pretty decent way to handle things (especially if core rulebook is fairly tight and only has one or two of them). Yeah, it can seem silly, but it can also provide DMs with a useful tool. I think we should also be clear about what we mean with "the twenty types of goblin problem". I think there's a difference between, for example, Rime of the Frostmaiden including "Icewind Kobolds," who are just like Monster Manual Kobolds except their Con score is higher (so they have more HP) and their gear is better, and Tomb of Annihilation including kobold subtypes like the "Inventor" and "Scale Sorcerer", who have specific abilities and powers beyond those of a basic kobold. The former strikes me as excess, something that could be handled with a note instead of a full statblock (increase the local kobolds' HP by 4 and AC by 2), but the latter strikes me as a decent reason to fully stat out these kobold subtypes for more variety in combat encounters. Maybe what I'm getting at is adding new goblin or kobold "subraces" strikes me as excessive, but adding new goblin or kobold "classes" is pretty useful.

|

|

|

|

The first episode of Ludonarrative Dissidents, a podcast where Ross Peyton, Greg Stolze and James Wallis look at RPG designs, dropped to backers yesterday (the full release is in a month). They were discussing BitD, and the following quote came up:Greg Stolze posted:"Everything that usually gets plotted, the rules are trying to do instead, with expectations that when you get to a point where you need creativity the GM is just going to pull something out of their rear end, be spontaneous and creative. And if you are capable of being spontaneous and creative in the middle of a game session, this is great, this is gonna be a terrific force multiplier for you, but if you are a person who under pressure when it's like 'ok, how is this GMC going to respond to this completely unexpected development?' and you just sit there and gawp like a caught fish, this is not the game for you. It is not gonna.. it tries to help you but if you can't be quick on the draw with a creative detail your game is not gonna be as rich as I think the text wants it to be." Now, I highly resemble this quote myself, but when I mentioned it and thought about it it seems decidedly off. First of all, there's no game where the GM doesn't have to be spontaneous and creative sometimes. Especially, Greg Stolze is the author of Unknown Armies which is extremely likely to trigger that requirement (it's a modern-day game, the PCs could technically just get on a plane anywhere). And yet, it still made sense to me and I can't put my finger on exactly why. (I did end up writing to them to point out that their "why people would play this" section was actually "why people would run this", which happens far too often with indie game commentary and encourages reverse facilitation which still seems bad to me.)

|

|

|

|

I think its true any game does require some GM improv (assuming the game in question does have a GM), unless it is so restrictive as to have very set things the PCs can or cant do and that space is small enough to keep in your head as a GM, however some games are indeed way better at telling you how to react to players than others. Anything in PbtA will have an Agenda the GM can fallback on when they need to think on what to do next, and even just the structure of a game can help in facilitating a good back and forth between players and GM.

|

|

|

|

What Stolze might be missing is that Blades gives explicit room for everybody to pull things out of their rear end if anything gets stuck. The NPCs for the most part have ties not only to each other but to the player characters, or through their factions, to the crew. It's an explicit caveat for the system that players need to be way more proactive than they might expect from other, more popular RPGs, and the tools are there to help that happen, and help document the resulting changes in state.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 7, 2024 18:37 |

|

I think "what might this NPC do.." was a bad example. Improvising "what's through the next door" is a ton more stressful.

|

|

|