|

Xander77 posted:Everything from "I must have fainted" to "his ugly teeth" was pasted twice. Thank you. Any idea what that cottonwood polka's in specific reference to?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 10, 2024 16:18 |

|

Arbite posted:Thank you. Any idea what that cottonwood polka's in specific reference to?

|

|

|

|

Yeah, I read it as him being hung up from a cottonwood tree, and tortured in whatever way to make him dance.

|

|

|

|

quote:At this point Sonsee-array, accompanied by the Yawner in case the prisoner proved violent, had flounced off for a final look at me, which I have described. She had then gone back to Papa and announced that she wanted to marry the boy. (Sensation.) Friends and relatives had now urged the unsuitability of the match; Sonsee-array had retorted that there were precedents for marrying pinda-lickoyee, including her own father, and it was untrue, as certain disappointed suitors (cries of “Oh!” and “Name them!”) had urged, that her intended was a scalp-hunting enemy; her good friend Alopay, daughter of Nopposo and wife to the celebrated Yawner, had been a captive with her and could testify that the adored object had taken no scalps. (Uproar, stilled by the arrival of the body in the case, with the Yawner at his elbow.) Too bad Flash never got around to Canada, I imagine him getting roaring drunk with everyone else at Charlottetown, some too hung over to stand for the big photo at the end... Well, at least we'll see a bit of Sam Grant in the fullness of time. quote:I said I was here as a trader, and there was an angry roar. Mangas Colorado leaned forward. “You trade in Mimbreno scalps to the Mexicanos!” he croaked. Flashman, whether in a panic or cool under pressure is always fun to see. quote:“So you say.” It was like gravel under a door. “But what do we know of you, save that you are pinda-lickoyee? How do we know you are a fit man for her?” There will be blood... next time! Arbite fucked around with this message at 17:02 on Apr 18, 2022 |

|

|

|

quote:This brought more hubbub, with Sonsee-array protesting, Vasco yelling savage agreement, and the mob roaring eagerly. Mangas nodded, so I asked for a lance and my pony. Ah, here we go. quote:Then I turned away, and damnably stiff and bruised as I was, vaulted on to the Arab’s back. I trotted him about for a moment or two, plucked the lance from the Yawner’s hand, and cantered away fifty yards or so before turning to come in on the pegs at a gallop. My heart was in my mouth, for while I’d been a dab hand in India, I knew I must be rusty as the deuce from lack of practice, to say nothing of my cracked head and groggy condition – and if I failed or made a fool of myself, I was a dead man. It is a beautiful sight. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Fcp_4rQPlU&t=185s quote:That was what I’d been after from the start – to make him look so ridiculous that his challenge to a man who was obviously more expert than he would be scoffed out of court. It had worked; even Mangas’s mouth twitched in a hideous grin, while the Yawner gaped and slapped his thighs. Vasco stamped and screamed in rage – and then his eye lighted on me; he shook his fist, sprang to his pony’s back, and made straight for me, yelling bloody murder, drawing his hatchet as he came. It's all relative. Let's see where the happy couple lie... next time!

|

|

|

|

Arbite posted:There was an instant’s hush, and then uproar, with everyone surging forward for a look, and Vasco’s pals to the fore, clamouring at Mangas for vengeance on the Yawner, who spat and sneered, with one hand on his knife. “The pinda-lickoyee was in my charge!” he snarled. “He was ready to fight – but this coward would have killed him unarmed!” Which I thought damned sound, and Mangas evidently agreed, for he quietened them with a tremendous bellow, stooped over the corpse, and then told them to take it away.

|

|

|

|

quote:Possibly because I’ve spent so much time as the unwilling guest of various barbarians around the world, I’ve learned to mistrust romances in which the white hero wins the awestruck regard of the silly savages by sporting a monocle or predicting a convenient eclipse, whereafter they worship him as a god, or make him a blood brother, and in no time he’s teaching ’em close order drill and crop rotation and generally running the whole show. In my experience, they know all about eclipses, and a monocle isn’t likely to impress an aborigine who wears a bone through his nose. So don’t imagine that my tent-pegging had impressed the Apaches overmuch; it hadn’t. I was alive because Sonsee-array fancied me and was grateful – and also because she was just the kind of minx to enjoy flouting tribal convention by marrying a foreigner. I’d come creditably out of the Vasco business – nobody mourned him, apparently – and Mangas had given me the nod, so that was that. But no one made me a blood brother, thank God, or I’d probably have caught hydrophobia, and as for worship – nobody gets that from those fellows. It's good to be self-aware and also keep things interesting. I think my only exposure to King Solomon's Mines was a radio drama growing up but it's very memorable in any form. quote:Having taken me on, though, he was prepared to make a go of it, and that same evening he inducted me into a peculiar Apache institution which, while revolting, is about the most clubbable function I’ve ever struck. After we had supped, he took me along to a singular adobe building near the fort, like a great beehive with a tiny door in one side; there were about forty male Apaches there, all stark naked, laughing and chattering, with Mangas among them. No one gave me a second glance, so I followed the Yawner’s example and stripped, and then we crawled inside, one after the other, into the most foetid, suffocating heat I’d ever experienced. Ooh, very lurid. Also White's still doesn't allow women to visit let alone join, while the Reform and Athenaeum only permitted women members in 1981 and 2002, respectively. quote:I had a further taste of Apache culture on the following day, when with the rest of the community I attended the great wailing funeral procession for the deceased Vasco, and for the victims of Gallantin’s massacre, whose bodies had been brought down from the valley in the hills. That was a spooky business, for there were two or three of my own bagging on those litters, each corpse with its face painted and scalp replaced (I wondered who’d matched ’em all up) and its weapons carried before. They buried them under rock piles near the big hill they call Ben Moor (and that gave me a jolt, if you like, for you know what big hill is in Gaelic – Ben Mhor. God knows if there’s a tribe of Scotch Apaches; I shouldn’t be surprised – those tartan buggers get everywhere). They lit purification fires after the burial, and marked the place with a cross, if you please, which I suppose they learned from the dagoes. Well, with that glorious badinage we'll call it. I'll see you all... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:We were sitting among the ruins by now and at this point he toppled slowly backwards and lay with his huge legs in the air, singing plaintively. God, he was drunk! But I must have been drunker, for presently he carried me home in one hand (I weighed about fourteen stone then) and dropped me into my wickiup – through the roof, not the door, unfortunately. But if my final memories of that celebration were confused, I’m clear about what he said earlier, and if it sounds like drunkard’s babble, just remark some of the things that supposedly simple savage knew – along with all his fanciful notions. And if that ain't a perfect example of racism just right on the page. Author's Note posted:Mangas (or Mangus) Colorado (1803?-1863), leader of the Santa Rita Copper Mines band of the Mimbreno Apaches, was one of the great Indian chiefs, certainly the most gifted of his nation, although less famous than his successors. Originally named Dasodaha (He-Only-Sits-There), he is supposed to have won the title of Red Sleeves by stealing a red shirt from a party of Americans; only Flashman suggests that it was in reference to his duel with his brothers-in-law – an encounter mentioned by Cremony. Although he was unusually large and powerful, there is some uncertainty as to how tall he was; some sources suggest as much as six feet six or seven, but Cremony, who knew him well a year or two after Flashman, settles for six feet, and John C. Reid, another eye-witness, simply says “Very large, powerful mould, villainous face” (Reid’s Tramp, by John C. Reid, 1858). What is not in dispute is Mangas’s intelligence and political ability; Cremony, although he despised his character and noted that he was not remarkable for personal bravery, thought him brilliant, statesmanlike, and influential beyond any other Indian of his time. As leader of the Mimbreno, Mangas showed great skill in unifying the Apache people, partly through marriage alliances; three of his daughters by the beautiful Mexican lady became wives of the Coyotero, Chiricahua, and White Mountains clans; one of his sons-in-law was the celebrated Cochise. Of the fourth daughter, Sonsee-array (the Morning Star), there is no historical trace; since she did not marry an Apache chief, like her sisters, she presumably had no political importance. quote:Speaking of Apaches in particular, you must understand that to them deceit is a virtue, lying a fine art, theft and murder a way of life, and torture a delightful recreation. Aha, says you, here’s old Flashy airing his prejudices, repeating ancient lies. By no means – I’m telling you what I learned at first hand – and remember, I’m a villain myself, who knows the real article when he sees it, and the ’Pash are the only folk I’ve struck who truly believe that villainy is admirable; they haven’t been brought up, you see, in a Christian religion that makes much of conscience and guilt. They reverence what we think of as evil; the bigger a rascal a man is, the more they respect him, which is why the likes of Mangas – whose duplicity and cunning were far more valued in the tribe than his fighting skill – and the Yawner, became great among them. This twisted morality is almost impossible for white folk to understand; they look for excuses, and say the poor savage don’t know right from wrong. Jack Cremony had the best answer to that: if you think an Apache can’t tell right from wrong – wrong him, and see what happens. Hmm, now I wonder if Ms. Leo Lade's Duke did eventually catch up with Flashy. quote:You see, it’s been the great illusion of our civilisation that when the poor heathen saw our steamships and elections and drains and bottled beer, he’d realize what a benighted rear end he’d been and come into the fold. But he don’t. Oh, he’ll take what he fancies, and can use (cheap booze and rifles, for example), but not on that account will he think we’re better. He knows different. This is in reference to the Ur where Abraham was born, not to be confused with the Uruk of Gilgamesh 60 kilometers to the northwest. Let's see where Flashman's ever vile mindset leads him... next time!

|

|

|

|

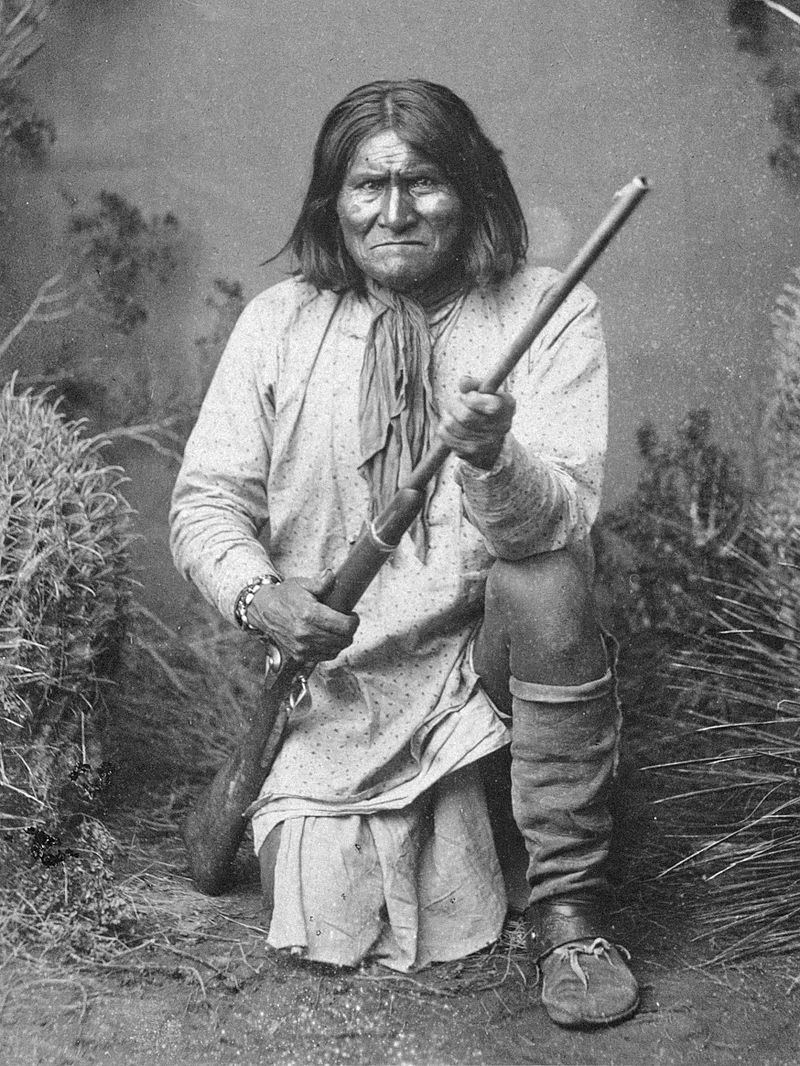

quote:The morning after Mangas’s tizwin party I was rousted out at dawn by a foul-tempered Yawner, who took me miles off into the hills, both with our heads splitting, to prepare for my honeymoon. We must find a pretty, secluded spot, he snarled, and build a bower for my bride’s reception; we lit on a little pine grove by a brook, and there we built a wickiup – or rather, he did, while I got in the way and made helpful suggestions, and he damned the day he’d ever seen me – and stored it with food and blankets and cooking gear. When it was done he glared at it, and then muttered that it would be none the worse for a bit of garden; he’d made one for Alopay, apparently, and she’d thought highly of it.  A beautiful moment of turnabout and revelation. Yawner (Goyaałé), later known around the world as Geronimo would try to survive fight against the enroaching Americans and Mexicans for decades, sometimes simultaneously. Author's Note posted:It is not remarkable that Flashman should have known Geronimo (1830?–1909), since at this time the great Apache, the grandson of a chief from another tribe, had settled among the Mimbreno following his marriage to Alopay. Known originally as Goyathlay (The-One-Who-Yawns), Geronimo was among the bitterest opponents of Mexico and the United States; his family had been killed by Mexicans, and he waged intermittent warfare in the south-west until Apache resistance was finally overcome by campaigns in the 1880s, conducted by Generals Crook and Nelson Miles. Geronimo was sent to Florida, but was allowed to spend his last days at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he became something of a tourist attraction. Since he was one of the most photographed of all Indians (once being snapped at the wheel of a car), there is ample confirmation of Flashman’s description. (See Geronimo’s Autobiography, edited by S. M. Barret, 1906; Bourke’s Apache Campaign and On the Border with Crook, 1891; Dunn.) quote:The wedding took place two days later, on the open space before the old fort at Santa Rita, and if my memories of the ceremony itself are fairly vague, it’s perhaps because the preliminaries were so singular. A great fire was lit before the old fort, and while the tribe watched from a distance, all the virgins trooped out giggling in their best dresses and sat round it in a great circle. Then the drummers started as darkness fell, and presently out shuffled the dancers, young bucks and boys, dressed in the most fantastic costumes, capering about the flames – the only time, by the way, that I’ve ever seen Indians dancing round a fire in the approved style. First came the spirit seekers, in coloured kilts with Aztec patterns and the long Apache leggings; they were all masked, and on their heads they bore peculiar frames decorated with coloured points and feathers and half-moons which swayed as they danced and chanted. They were fully-armed, and shook their stone-clubs and lances to drive away devils while they asked God (Montezuma, I believe) for a blessing on Sonsee-array and, presumably, me. After this project finishes we'll have to do a full count of the amount of ritual bondings Flash goes through over the course of the series (don't start yet). quote:I know she was no great beauty – not to compare with Elspeth or Lola or Cleonie or the Silk One or Susie or Narreeman or Fetnab or Lakshmibai or Lily Langtry or Valla or Cassy or Irma or the Empress Tzu’si or that big German wench off the Haymarket whose name escapes me (by Jove, I can’t complain, at the end of the day, can I?) – but by the time the third evening was reached if you had asked me my carnal ideal of womanhood I’d have described it as just over five feet tall, sturdy and nimble, wearing a beaded tunic and white doeskin leggings, with a round chubby face, sulky lips, and great slanting black eyes that looked everywhere but at me. God, but she was pleased with herself, that smug, dumpy, nose-in-the-air wench, and I must have been about to burst when the Yawner tapped me on the shoulder and jerked his head, and when I got up and panted my way out of the firelight, no one paid the least notice. It's good he included Susie at the top there. And also, that's the end of that chapter! He's loved and/or accepted by all around, let's see if (how) he fucks it all up... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:There’s nothing like teaching a new bride old tricks, and by the time our forest idyll was over I flatter myself Sonsee-array was a happier and wiser woman. Ten days was enough of it, though, for she was an avid little beast who preferred quantity to quality – unlike Elspeth, for example, whose beguiling innocence masked the most lecherously inventive mind of the last century, and whose conduct on our honeymoon would have caused the good citizens of nearby Troon to burn her at the stake, if they’d known. No, young Sonsee-array was more like Duchess Irma, who on discovering a good thing couldn’t get enough of it, but where rogering had melted Irma’s imperious nature to the point where she was prepared to await her lord’s pleasure, my spirited Apache knew no such restraint. When she wanted her bells rung, she said so – she was tough, too, and discovered a great fondness for committing the capital act standing up under a waterfall in our stream; no wonder I’ve got rheumatism today, but it’s worth it for the memory of that wet brown body lying back in my supporting arms while the water cascaded down over her upturned face, with me grinding away up to my knees in the shallows. Hee hee. quote:Sonsee-array and I returned to the Copper Mines just as the community was moving into winter quarters in the hills, and if you wonder why I hadn’t taken advantage of our solitary state on honeymoon to make a break for freedom – well, I still didn’t know where I was, even, and although we’d been undisturbed. I’d had a shrewd idea that the Yawner and Quick Killer were never far away. Now, to make matters worse, the tribe moved about thirty miles south-west, farther than ever from the Del Norte and safety, into a mountainous forest where if I’d been fool enough to run I’d have been lost and recaptured in no time. Flash certainly isn't softening as he recollects. quote:They knew how to fight, too, after their fashion, far better than the Plains Tribes; given numbers, they might be holding out in Arizona yet, for bar the Pathans they were the best guerrillas ever I saw. They train their boys from infancy in every art of woodcraft and ambush and decoy (and theft), which is the way they love to make war, rather than in open battle. That winter in the Gila hills I saw lads of six and seven made to run up and down mountains, lie doggo for hours, spend nights half-naked in the snow, track each other through the brush, run off horses, and exercise constantly with club and knife, axe and lance, sling and bow. Damned good they are, too, but best of all – they could vanish into thin air. Lucky he had the interpreter when dealing with the Navajo. So, what's to become of him when spring arrives? We'll find out.. next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:From all this you’ll gather that it was a damned long winter, and made no easier by the fact that a male Apache does nothing in all that time except a little light hunting; for the rest he loafs, eats, sleeps, drinks, and thinks up devilment for the spring, so that in addition to being miserable and fearful, I was also bored – when you find yourself glad even of Mangas Colorado to talk to, by God you’re in a bad way. The only worthwhile amusement was teaching Sonsee-array new positions – for there was no question of so much as looking at another female, even if I’d dared or wanted to; they’re fearfully hot against adultery, you see, and punish it by clipping the errant female’s nose off – what they do to the man I was careful not to inquire. There's always that mix of comeuppance and celebration that makes Flashman bearable and fascinating. quote:There were perhaps a hundred of us setting out from the hill camp that day, including all the principal men of the tribe, Mangas himself, Delgadito, Black Knife, Iron Eyes, Ponce, the Yawner, and Quick Killer; every horse in the valley had been pressed into service, for the Apaches were by no means so flush of horse-flesh then as they became later, and about a quarter of our command were afoot. The medicine men inspected us to make sure we had our talismans and medicine cords, and that the younger fellows had their scratching-tubes; then they threw pollen at the sun, chanting, and off we went, in five groups as we left the hills, which is the Apache style on the warpath, the separate bands scouring the country and converging on the main objective. My heart leaped as I heard Mangas shouting in their dialect to the infantry groups as they branched off north-east across the plain, and I caught the name “Fra Cristobal”. For that lay north on the Del Norte, not far south of Socorro, and if I couldn’t win to safety between here and there – well, there would be something far wrong. Needless to say, there was. Nope, 100% natural formation according to Fraser.     quote:We camped that night in a shallow river-bottom filled with cotton-woods, and rode on next day through broken country which began to incline slowly downwards; my excitement rose, for I guessed we must be approaching the Del Norte valley. Sure enough, in the late afternoon we came out of low hills, and there below us in the fading light of sunset lay the familiar fringe of cottonwoods, with here and there a gleam of water amongst them, and low scraggy bluffs beyond. Just over the river smoke was rising from a fair-sized village, all peaceful in the last rays of the afternoon sun. As we dismounted, my heart was thumping fit to burst as I realized that if this was our quarry, I’d never get a better chance to break. And we saw or will see all of those except for the ride with Stuart. Unless he's referring to a Civil War ride with Custer in which case no, sadly not. We can compare this raid with the ones seen earlier... next time!

|

|

|

|

I think this sequence (and a lot of others throughout this book) emphasise how much of a potential action hero Flashman is. To many readers, who aren't accustomed to unthinking boys own heroism from their protagonists, he would appear, if not exactly courageous, to be very assured and cool in dangerous situations. Really his only let-downs are not wanting to gallantly stick it out when all appears lost, and his unwillingness to go risk his life unless he has to. But outside of adventure novels, most of us would agree with that latter part! He's obviously a competent enough soldier to take part in this war party without disgrace (this bit strains credulity slightly - he describes the Apache expertise in irregular warfare, but he doesn't mention being given any training in their tactics or familiarisation with the local terrain), he understands that the risks by military standards are minimal. But he's cool enough to disregard the minor risks of being shot during the raid etc, and focus on when is the best chance to risk his life by escaping, presumably because to him, living out his life among the Apache is worse than dying.

|

|

|

|

I’d love to read the author’s wartime memoirs. Can anyone who’s read them say if he talks about being scared out of his mind and not wanting to fight?

|

|

|

|

poisonpill posted:I’d love to read the author’s wartime memoirs. Can anyone who’s read them say if he talks about being scared out of his mind and not wanting to fight?

|

|

|

|

Xander77 posted:It's incredibly formulaic "sure, I was scared the whole time. I was no hero - I was just doing my job, looking out for my buddies who were depending on me" stuff. (That's "Quartered Safe Out Here" - his adventures with the Scottish comic relief troop are combat-free) Errr except for about every 20 minutes he turns into that weird UKIP guy down the pub ranting for a few pages about how the Empire has gone downhill or how much he enjoyed shooting fleeing Japanese soldiers in the back. This becomes more true you get further into the book, it's fairly

|

|

|

|

feedmegin posted:Errr except for about every 20 minutes he turns into that weird UKIP guy down the pub ranting for a few pages about how the Empire has gone downhill or how much he enjoyed shooting fleeing Japanese soldiers in the back. This becomes more true you get further into the book, it's fairly I will concede that his political outlook is very outdated, he certainly seems to have been the sort of bloke who'd refuse to admit the Empire was fundamentally a project for material/economic gain, and drat any human cost. I dispute the characterisation that he says he enjoyed shooting fleeing Japanese soldiers in the back though. He specifically describes sighting down his rifle at enemy soldiers (who I think were retreating, or at any rate caught out at a disadvantage and out of cover, not firing back) and says he felt no shame or hesitation, just satisfaction at scoring hits. That seems a fairly honest and reasonable point about his mindset at the time - I don't think many soldiers in war do feel much internal conflict about killing in the moment. And shooting the enemy whilst they're in disarray is not at all against the rules of war, it's sort of considered the ideal time. 'Fleeing soldiers' isn't the same as soldiers who are surrendering, they tend to be running off to take up new positions and resume shooting at you. There's a separate point to be made about why he felt the need to insist he didn't feel any regret about killing during the war. I certainly don't think his views were beyond reproach. But if you consider him an unusually bloodthirsty person based on his memoir, I have similarly bad news about a huge proportion of the people who served in combat in WW2 (or any war).

|

|

|

|

Genghis Cohen posted:he certainly seems to have been the sort of bloke who'd refuse to admit the Empire was fundamentally a project for material/economic gain, and drat any human cost. Not disagreeing since I haven’t read it, but how does this square with the Flashman presentation of the Empire as a rapacious amoral greedy violent machine?

|

|

|

|

poisonpill posted:Not disagreeing since I haven’t read it, but how does this square with the Flashman presentation of the Empire as a rapacious amoral greedy violent machine? I think his view may have fallen somewhere between Flashman's amorality and the staunch heroism of the characters he was parodying? Like Fraser does seem to admit there was hypocrisy and cruelty in the Empire, but he also seems to see something to admire in the Christian morality and 'civilising mission' that some of the colonialists did at least partly believe in. How many universities did Britain build in India, etc. Whereas we now might say, well, the Indians didn't want the UK to import great swathes of their institutions to rule over them, so the UK shouldn't have done it, Fraser might think that those institutions were better than what the Indians had previously, so on the balance it was a good thing. Basically I think he acknowledges the Empire had its flaws, but he retains more affection for it than most observers of later generations.

|

|

|

|

poisonpill posted:Not disagreeing since I haven’t read it, but how does this square with the Flashman presentation of the Empire as a rapacious amoral greedy violent machine? You will note the later the book, the more he tends to be sympathetic to it (while still acknowledging its flaws)

|

|

|

|

A big part of the Flashman books (often not just subtext, but black-and-white stated text) is that while the British Empire was a exploitative machine that expanded through violence and tried to cover it up with a bunch of hypocritical wheezing about bringing the gifts of civilization to the benighted heathen savage, the rulers they were displacing were every bit as awful (if not worse) to their populace than the Brits were, so really everyone is a bastard when you get right down to it, no one has any moral standing, and the strong dominate the weak (so always try to get on the side of the strong, like Flashman).

|

|

|

|

Yea, true. It’s not racist or nationalist in the sense that I’d judge Fraiser to believe English culture or English people are in any sense better or morally superior than any of the people from Africa, Asia, Europe… The English were just better at taking what they could, which is at least a utilitarian positive.

|

|

|

|

feedmegin posted:Errr except for about every 20 minutes he turns into that weird UKIP guy down the pub ranting for a few pages about how the Empire has gone downhill or how much he enjoyed shooting fleeing Japanese soldiers in the back. This becomes more true you get further into the book, it's fairly

|

|

|

|

quote:I swerved after Iron Eyes under the cottonwoods behind the village – and my eyes were already straining ahead towards the low bluffs beyond. If I could drop out of sight in the confusion, and make my way through the dusk, it might be hours before they realised I’d gone, and by that time I’d be flying north along the east bank of the Del Norte – by God, and I wouldn’t stop till I reached Socorro at least … Does the barest hint of good as he makes his flight, let's see where that gets him. quote:I was free! After six months with those hellish brutes I was riding clear, and within a day – two days at most – of safety among my own kind. However fast Mangas and his mob of fiends moved up the west bank, I must be flying ahead of them; I could have yelled with delight as I pressed ahead at a steady hard gallop, feeling the game little Arab surge along beneath me. Dark was coming down, and stars were showing clear in the purple vault overhead, but I was determined to put a good twenty miles between me and possible pursuit before I halted. They must miss me by tomorrow, and knowing their skill in tracking, I didn’t doubt that they would pick up the Arab’s trail eventually, but by then I would have a day’s lead of them; I might even have found a large enough settlement to count myself safe. New small horrors notwithstanding he seems to have made a clean break of it. quote:I squatted there trembling, and in sudden revulsion kicked the ghastly thing aside. It rattled off the road, and came to rest beside a pile of white sticks which I realised with a thrill of horror was the skeleton of some large beast – an ox or a horse which must have died beside the wagon-tracks. As I stared fearfully ahead I saw in the fading moonlight that there were other similar piles here and there … skeletons of men and animals beside a deserted road in the middle of a great waterless plain of rock and sand. It rushed in on me with frightening certainty; I knew where I was, all right. There was only one place in the whole of this cursed land of New Mexico that it could be – by some dreadful mischance I had strayed into the Jornada del Muerto – the terrible Journey of the Dead Man. Dying by his own path instead of getting shot in the back would also be fitting, let's see what awaits him... next time!

|

|

|

|

Poor horsie.

|

|

|

|

reading it a few pages at a time like this really highlights how goddam good Fraser is at this

|

|

|

|

quote:Something touched the back of my neck – something wet and cold, and I rolled over with a gasp of fear to find the Arab nuzzling at me. By God, his muzzle was soaking! I stared ahead – there were other pools – one of them must be fresh, then! I lurched up and ran to the nearest, but the clever little brute trotted on to stand by a farther pool, so I followed, and a moment later I was face down in clear, delicious water, letting it pour until it almost choked me, rolling in the stuff while the little Arab came for another swig, dipping daintily like the gentleman he was. I fairly hugged him, and then saw to it that he drank until he was fit to burst. Passages like these make you appreciate the little necessities. quote:I gave him the last of the water, telling myself that we must come on a stream in an hour or two, for the Jornada desert was petering out into mesa studded with sage and greasewood, and there were dimly-seen hills on the northern horizon; I trotted on, turning at every mile to stare through the shimmering heat haze southwards, but there was no movement in that burning emptiness. Then it began to blow from the west, a fierce, hot wind that grew to a furnace heat, sending the tumbleweed bouncing by and whirling up sand-spouts twenty feet high; we staggered on through that blinding, stinging hail for more than an hour in an agony of thirst and exhaustion, and just when I was beginning to despair of ever reaching water, we came on a wide riverbed with a little trickle coursing through its bottom. In the dust-storm I’d have passed it by, but the little Arab nosed it out, whinnying with excitement, and in a moment we were both gulping down that cool delicious nectar, wallowing in it to our hearts’ content. Hahahah! Good grief. quote:One moment it was whole, the next it was trailing loose in my hands. I believe I screamed aloud, and then I had my fists wrapped in the Arab’s mane, holding on for dear life, crouching down as a gunshot cracked out behind – there was precious little chance they’d hit me, but now as I raised my head, an infinitely worse peril loomed before me. Out on the flat I had little to fear, but once into those rocky ravines and forested slopes my Arab’s speed would count for nothing; I must keep to the open, for my life – but even as I prepared to swerve I saw to my horror that already I’d come too far; there were tongues of forest reaching down to the plain on both my flanks, I was heading into the mouth of a valley, it was too late to turn aside, and nothing for it but to race deeper into the trap, with the triumphant screams of the Apaches rising behind me. Well, there's more of that water he wanted. I'm more worried about the horse, let's learn what we can... next time!

|

|

|

|

The horse is the real hero.

|

|

|

|

quote:I came out of it like a leaping salmon, floundering round to face the Apache – his riderless mustang was clattering away, and the Indian himself was writhing on the stones in his death agony; I saw him heave and shudder into stillness – but when I looked round the buckskin man was no longer there. The rock was empty, there wasn’t a sign of life among the trees and bushes fringing the gully – had I dreamed him? No, there was a wisp of smoke in the still air, there was the dead Apache – and round the bend, whooping in hellish triumph at sight of me, came Iron Eyes with two other screaming devils hard on his heels. He flung himself from his pony and raced towards the stream, lance in hand. *"White-eyed man, you are about to die!" quote:He glanced at me, and then said something quietly in Apache, and the two braves gaped and then screamed defiance. The small chap shook his head and pointed down the valley; there was another crashing volley, followed by screams and the neighing of horses and the crack of single shots; even in my pain and bewilderment I concluded that some stout lads were decreasing the Mimbreno population most handily – and the nearest Apache rolled his eyes, yelled bloody murder, and he and his mate came at me like tigers, hatchets foremost. Hard to decide which rescue this is most reminiscent of, probably when Brooke & Co. saved him in Singapore, though the scenery is closer to the hunting at Balmoral... quote:I was glad someone had mentioned that, for my arm was running like a tap, and if there’s one thing that makes me giddy it’s the sight of my own blood. What with that, the pain of my wound, the terror of the chase and of the bloody slaughter I had witnessed, I was about all in, but now they were all round me, grimed white faces staring curiosity and concern as they gave me Christian spirits – first down my throat, then on my wound, which made me yelp – and patched me up, asking no questions. A trooper gave me some beef and hard-tack, and I munched weakly, marvelling at the miracle that had brought them to my rescue – especially the supernatural appearance of the gently-spoken little fighting fury in buckskin; there he was now, squatted by the stream, carefully washing and drying the knife that had felled Iron Eyes. And who are these rescuers, really? We'll find out that as we begin the last chapter of this era... next time!

|

|

|

|

quote:Maxwell claimed later that the arrow which wounded me must have been poisoned, and indeed there are some who say that the ’Pashes doctor their shafts with rattlesnake venom and putrid meat and the like. I don’t believe it myself; I never heard of it among the Mimbreno, and besides, any arrow which has been handled by an Apache, or even been within a mile of him, doesn’t need poisoning. No, I reckon they were just good old-fashioned wickiup germs that got into my system through that shoulder wound, and blew my arm up to twice its normal size, so that I babbled in delirium all the way to Las Vegas. It's interesting that this passage makes a serious and joking mention of the folly of absolutism. quote:I’d been at Las Vegas a week when Maxwell rolled up, in great fettle; they’d not only intercepted the Jicarillas and killed five of them, but had also recovered the stolen horses, and he was now on his way back to his place at Rayado, up by Taos. He pooh-poohed my thanks jovially – I was sitting up in my cot in Barclay’s back-parlour looking pale and interesting – and was all agog to know who I was, for there hadn’t been time to introduce myself before I’d keeled over, and how I’d come to be booming up from the Jornada with paint on my face and a war-party at my heels. I was just preparing to launch into a carefully-prepared tale, leaving out such uncomfortable details as scalp-hunting and being Mangas Colorado’s son-in-law, when who should slip in but the small man in buckskin. A rare instinct to kick in for him, must have made it all the more persuasive. quote:It was as well I did, too. I told them my real name, since it was one I hadn’t used in America (except among the ’Pash) and that I’d been on my way to Mexico when I’d fallen in with Gallantin and found myself in a scalp-hunting raid before I knew it; I made no bones about how Sonsee-array had protected me, or how I’d absconded at the first opportunity – Maxwell whistled and exclaimed as though he didn’t believe half of it, but when I’d done Carson nodded thoughtfully and says:     Author's Note posted:Christopher “Kit” Carson (1809–68), guide, scout, Mountain Man and soldier, is one of the great Americans, and by all accounts, even when revisionists have combed his history for faults, seems to have been every bit as likeable as Flashman makes him sound. Only one or two points need to be made here, in relation to Flashman’s account: 1) Carson pursued Apache horse-thieves south from Rayado in March, 1850, with a party of friends and dragoons, recaptured the horses, and killed five Indians. This fits precisely with Flashman’s story, and only one question arises: either Carson’s party went 200 miles south in their pursuit (which is unlikely, but not impossible), or else Flashman has misjudged time and distance again, and was chased farther north by Iron Eyes’ band than his account suggests. The nature of the ground where Iron Eyes ran him to earth and Carson rescued him suggests the latter; his flight north may have taken a day longer than he says it did. 2) His description of Carson is accurate: the great scout was 40 at this time, clean-shaven, small and compact in build, soft-spoken, and with twinkling grey eyes, according to others who knew him. That he was illiterate seems doubtful; one biographer states flatly that he owned more than a hundred books and wrote a good clear hand; he certainly spoke French, Spanish, and several Indian dialects fluently, and does not appear to have spoken like an uneducated man. 3) Flashman says Charles Carson was a year old in the spring of 1850; historians give varying dates for the birth of the child, between 1849 and 1850. 4) Flashman’s memory is playing him false about the name of the hunter who went with them to Laramie; he is variously described as Goodall and Goodel, but not Goodwin. For the rest, the account of the journey and its purpose fits with Carson’s movements at this time; the story on pp.260 ff. is true, as is the story of Mrs White and the novelette on p.263. 5) Carson was nick-named, among other things, the “Nestor of the Plains”, and it is likely that Maxwell was using the name in jest. 6) Lucien Maxwell (1818–1875), a former Mountain Man and hunter, was a close friend of Carson’s, but of much greater ambition and worldly ability; he seems to have been a charming rascal and an intrepid frontiersman, but although he did control one of the largest private empires ever known (the Maxwell Land Grant), he died comparatively poor. (The Life and Adventures of Kit Carson, by Dewitt C. Peters, 1859; Kit Carson, by Noel B. Gerson, 1965; Dear Old Kit, by H. L. Carter; Kit Carson, by Stanley Vestal; Inman, Lavender, Bancroft.) No shortage of fascinating fellows on these adventures. Unsurprisingly Carson's great abilities at his chosen life have made him as great a hero and terrible a villain as individuals judged appropriate to their times. We'll be off again... next time. Arbite fucked around with this message at 07:45 on May 22, 2022 |

|

|

|

quote:So that was how I came to ride north with Kit Carson in the spring of ’50, whereby I came safe to England eventually – and into such deadly peril, years later, as I’ve seldom faced in my life. But that was something I couldn’t foresee, thank God, when a week later we made the two-day ride north to Rayado, a pleasant little valley in the hills where Maxwell and Carson had made their homes. They were an oddly-assorted pair, those two – Maxwell, the jovial companion, frontier aristocrat, and shrewd speculator who saw where the real wealth of the west was to be found, and built his modest farm at Rayado into the largest private estate in the history of the whole wide world; and Carson, the little gentle whirlwind whose eyes were forever straying to the crest of the next hill, who loved the wild like a poet, and asked no greater possession than a few acres for his beasts and a modest house for his wife and son. Between ourselves, I didn’t care for him all that much; for one thing, he had greatness, in his way, and I don’t cotton to that; for another, although he was always amiable and considerate, I guessed he was leery of me. He knew a rogue when he saw one – and we rogues know when we’ve been seen. Years later Flash would read that happening to him, but rather more accurately. quote:I imagined his reading it was just a brag, to show how famous he was, but then he told me where he’d come by the book. The previous autumn, he’d been one of a rescue party chasing a band of Jicarillas who had wiped out a small caravan and carried off a Mrs White and her baby; Carson’s folk hadn’t been able to save her life, or the baby’s, although they’d hammered the redsticks handsomely, and afterwards, in the dead woman’s effects, he had come across the novelette. It troubled him. Speaking of living in hope (or not)... quote:“She will be grieving at your absence.” And we will get more of Carson's views... next time! Also the reach of the Siouan language is hardly exaggerated.

|

|

|

|

So interesting when Flash meets his match with someone. It definitely breaks up the chain of endless mishap and lies. And my god, the descriptions make me want to head out to the old west with a horse.

|

|

|

|

poisonpill posted:And my god, the descriptions make me want to head out to the old west with a horse.

|

|

|

|

poisonpill posted:So interesting when Flash meets his match with someone. It definitely breaks up the chain of endless mishap and lies. And my god, the descriptions make me want to head out to the old west with a horse. As someone who lives there now, hope you like interstate and in-fill.

|

|

|

|

quote:“Smart Injun,” was his verdict. “Sees a long way, and clear. They’ll go, as the buffalo go, which it will, with all the new folks coming west. I won’t grieve too much for the ’Pash; they have bad hearts, and I wouldn’t trust a one of ’em. Or the Utes. But I can be right sorry for the Plains folk; the world will eat them up. Not in my time, though.” Not just good at painting landscapes, this man. quote:None of ’em offered us the slightest offence – though whether they’d have been as amiable if Carson hadn’t been along, I don’t care to think, for I gathered from him that there was a great discontent beginning to brew among them. They’d been trading about Laramie for years, peaceful enough, but after the cholera of the previous summer, which they blamed, rightly enough, on the immigrants, they were casting dark looks at the trains that came pouring westward in this summer of ’50. Before 1849 there had been wagons enough on the trails, but nothing to the multitude that now followed the gold strike. I’ve been told that more than 100,000 pioneers crossed the plains in ’50; from what I saw myself at Laramie and westward it was just a continuous procession – and I would say that was the year the Plains tribes realized for the first time that here was the rising of a white tide that was going to engulf their land – and their life. And here comes one more great introduction: quote:He had his nephew with him on the hunt, a pale, bright-eyed skinny little shaver who couldn’t have been above five or six years old, and was unique among all the Indians I ever saw, for his hair was almost fair. He sat very quiet among the feasters, and looked askance whenever anyone caught his eye. I found him watching me once and winked at him; he started like a rabbit, but a minute later our eyes met and he tried to wink back, shyly, but couldn’t close one eye without shutting the other, and when I laughed and winked again he giggled and covered his face. Spotted Tail growled at him to be still and mind what he was about, and the child whispered something which made his neighbours roar with laughter, at which Spotted Tail snapped at him threateningly. I asked what the boy had said, and Spotted Tail told me, glowering at the infant: We'll be seeing that one again much later, and will be wrapping up this age of the story... next time.

|

|

|

|

quote:We came to Fort Laramie next day, through a sea of prairie schooners and immigrant tents and Army horse lines and Indian lodges, all clustered for a couple of miles round the great adobe stockade by the Platte; there were caravans coming in and caravans leaving, traders white and Indian hawking their wares, dragoons drilling beneath the walls, and such a Babel as I hadn’t seen since Santa Fe or Independence. When word spread that Carson had arrived there was such a press of folk to see the great man that it was only with difficulty that we got our mules to the corral, and while Goodwin began the bargaining with teamsters from the trains, Kit and I went off to the post kitchen, ostensibly to see about grub, but in fact so that Carson could get out of the public eye – he hated to be stared at, especially because, as he told me in a rare burst of confidence, people were so disappointed because he wasn’t twenty feet tall. This bit's great. quote:Kit sighed again, and then glanced at me. Now, while he was in his usual old buckshkins, I was in the full prairie fig that Maxwell had given me, fringed beaded jacket and breeches and wideawake hat, with a Colt on my rump and a Bowie in my boot, and as you know I’m six feet odd and stalwart with it; you never saw such an image of a prairie hero in your life. Carson smiled, looked at the Arkansas boy, and gave an almost imperceptible nod in my direction. The hayseed swung round to me, and a huge beam of joy broke over his ruddy countenance as he looked me up and down. And one more scare for good measure. quote:I nearly fell out of my saddle. How the hell had he heard about Susie? I gaped at him, and regained my wits. “Good lord, no! That’s a … a woman I met in the East – we were companions, don’t you know … er … who … told you about her?” 'As I swung aboard the little Arab...' It lived! The horse lived! Hoorah!  And that brings us to the end of part one. Desperate escapes and many fascinating encounters, were had, along with the most starry eyed adoration of a landscape ever put to paper. Now that we're halfway through, what do you think about the book so far?

|

|

|

|

I once read something like 100 pages of a novel before it dawned on me that I'd already read it. Flashman books would be the complete opposite where, especially with the well-chosen excerpts you've put together, long strings of sentences have stayed with me and I recall almost verbatim, though it's been maybe 15 years since I read them. I'm native New Zealand maori and where we've obtained a constructive coexistence with our English colonists, the impending future (from the novels point of view) of American Indian races is sad and distressing to say the least. I remember the upcoming in part two tribal negotiations as especially aggravating and we know Harry well enough by this stage to understand he thinks they really are a dignified people and very hard done by. Hope this response encourages you! I use the 'awful' app, and new Flashman posts I always save until I'm sitting somewhere comfy.

|

|

|

|

Yeah this is highly entertaining. I love the vividness of his description.

|

|

|

|

Arbite posted:

Hooray! Best horse. This isn't one I've read before, so it's been interesting reading.

|

|

|

|

quote:It’s only when you’ve grown old that you begin to see that life doesn’t run in a straight line; that you can never be sure a chapter is finished, and that half a century may lie between cause and final effect. Why, I met Lola Montez and Bismarck in ’42, bedding one and belittling t’other, and thought that was that – and five years later they popped up to give me the scare of my life. And I thought I’d seen the last of Tiger Jack Moran after Rorke’s Drift – but, damme, he came back to haunt my old age and almost had me indicted for murder. No, you never can tell when the past is going to catch up, especially a past as dirty as mine. So now we jump twenty-five years forward and it's as graceful a leap as you would expect from Fraser. quote:“Neither I have,” says I. “Well, there’s a lot of it, you know. Difficult to take in, and it’s a long way.” She does know how to work him. quote:Since she had already bought the tickets, that was how we came to be at Phil Sheridan’s wedding in Chicago a few months later, and there, with a startling coincidence, began the bewildering chain of events which completed the story that I have told you in this memoir so far. (At least, I hope to God it’s complete at last.) Not all that happened in ’49 has a bearing on what I’m about to tell, for life’s like that, but much of it did. I can safely say that had it not been for my odyssey which began in Orleans and ended at Fort Laramie in ’50, the history of the West would have been different. George Custer might still be boring ’em stiff at the Century Club, Reno wouldn’t have drunk himself to death, a host of Indians and cavalrymen would probably have lived longer, and I’d have been spared a supreme terror as well as a … no, I shan’t call it a heartbreak, for my old pump is too calloused an article to break. But it can feel a twist, even now, when I look back and see that lone rider silhouetted against the skyline at sunset, with the faint eerie whistle of Garryowen drifting down the wind, and when I had rubbed the mist from my eyes, it was gone.  And the names will be dropped fast & furious real soon, or should I say... next time! Arbite fucked around with this message at 02:45 on Jun 9, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 10, 2024 16:18 |

|

Duplicated paragraphs there.

|

|

|