|

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 7, 2024 07:57 |

|

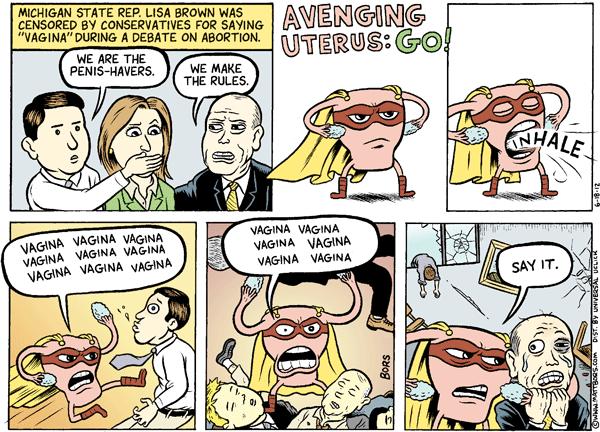

call me nostalgic but I think we could use some good old fashioned man-hating harpies

|

|

|

|

For a fleeting moment in 2021, Senator Richard Blumenthal traded away his blue suit and American-flag lapel pin. The stiff-backed, deep-pocketed Democratic lion of Stamford, Connecticut took to posing instead as… an unsupervised thirteen-year-old searching for dieting tips on Instagram: just another girl online. Recent Facebook leaks had revealed the netherworld of teen girls sacrificed to the platform’s beasts—psychoses, addictions, cruelties. Who would rescue the girls from the algorithms? The senator may have falsely claimed to have done a tour in Vietnam, but now he was facing real danger, putting himself in harm’s and lechers’ and advertisers’ way to come out on the other end with a solemn briefing for the American people: Silicon Valley whizzes were turning girls into itchy phone addicts and anorexics. The platform’s recommendation pages “latch on to a person’s insecurities, a young woman’s vulnerabilities about their bodies and drag them into dark places,” the senator pronounced, a Pericles for the online age. “Will you commit to ending Finsta?” he probed at a Facebook Senate hearing. Blumenthal’s odd ruse was of the moment. We are increasingly being made to understand that social media is the destroyer of the young and, more specifically, of young girls. Behold the great waste and decimation of the fairer youth: the sorry overexposure, the clueless sexuality, the incoherent argot, the berserk self-fashioning and smashed-up psyches. Weighing such dystopian portrayals, I polled my teenage sister, who reported only a wholesome Instagram diet of NASA images and cat memes. Might there be, despite the jeremiads, a silent majority of the innocently online? Might girls ever be something more than the mere victims of social media? Online, the girl proliferates herself as a meme, she overidentifies (“it me”), she felt cute might delete later. These girlish strains of narcissism are so endemic to social media that even as girls purportedly lose on the internet, a girlish mode of expression and Goffmanian self-presentation have won out among swelling ranks of users—including many who are not themselves girls. Consider the uber-feminine, uber-juvenile ecosystem today. Girl talk—with its lowercase run-ons, inscrutable acronyms and cheerful incoherence—is fluently adopted online. “Beauty breaks in everywhere,” Emerson said, but on Twitter, it’s exclamation marks breaking in for no apparent reason. Ditzy “likes” get expertly parallel-parked in the middle of sentences to tone down what are sometimes even smart thoughts, while “so obsessed with” swirls around like a fever dream courtesy of Bourdieu. Women more than twice the age of a teen songstress weigh in on having or not having a driver’s license. Hysteria is the self-diagnosed malady du jour. ● Among the chattering class, the girl persona signals a self-reflexively ironic, unprofessional professionalism. “I love being a girl,” an Ivy League-educated writer of cachet and/or accomplishment broadcasts alongside a text screenshot, her six-figure Publishers Marketplace deal hovering above in the digital firmament. (What “girl” isn’t “writing a book!!!”?) Meanwhile, Lauren Oyler’s protagonist in Fake Accounts describes her Twitter avatar—as if pulling back the curtain on her own cynicism—as one “in which my hair completely covers my eyes and nose, representing me as a poutily sexy girl without a face.” Even the Nobel Laureate in literature is not exempt from girlification. Twitter celebrated Annie Ernaux’s lifetime of exquisite self-writing as a win for “literary hotties.” There must be something that women—I mean, “girls”—gain in performing abjection and excess, winky-faced incompetence and helplessness, vanity, faux-naïveté and a childish immunity to self-awareness online. Or, as the cunning Joanna Walsh writes in her recent book Girl Online: A User Manual, “Onscreen, woman defaults to girl.” Between scrolls, snaps and grams flows an unstoppable torrent of chic dissimulation, fast words and compulsive posting. Walsh continues: Offscreen, I have demonstrable experience that cannot be denied: age, class, race seed in my body as visible values. Only onscreen can I stand in that girl position limited only by eternal potential, an AI Alice, whatever my situation on the other side of the looking glass. In Walsh’s online wonderland, voyeurs look less at what is being said or done than how a user styles a self-image. Call it the digitized male gaze (or don’t), but when it comes right down to it, a senator impersonating a girl online is nothing special. Who on social media is not aspiring to the girl’s image of fun and flippancy? Cyborgians, cyberfeminists, latter-day “glitch feminists”—none of them had it quite right. Thwarting the optimists, the internet did not open users up to a bouquet of identities that elude gender. Rather, it reduced it to one. A girl online, Walsh cheekily writes, “is an avatar for everyone.” ● Categorizing Joanna Walsh’s little book is no easy task. Walsh herself claims it is a “user manual,” a work of “literary criticism,” a “memoir of motherhood,” “chick lit,” “feminist autotheory” and a “historical novel about the internet in the 2000s.” The ideal reader, she notes, is not you or me but, somewhat perplexingly, the internet itself. Sections of the book break down into bonkers binary code, detail the obscure history of Turing’s “child machine,” dip into dense media theory and dole out slapstick fitness-influencer tips. (If these “thought experiments,” as she terms them, sound daunting, perhaps update your browser.) Set in the mid-aughts, the book also documents how the internet fractured the life of the autofictional narrator. References to Alice Through the Looking-Glass help track Walsh’s transformation from a house-barricaded wife in front of a screen to a free-floating girl writing online. In the first half of the book, Walsh is merely “relational” to others; she is, as she writes, only “context.” She cleans Airbnbs and discusses Kafka’s manuscripts with her twelve-year-old son (Kafka, the great chronicler of selfhood warped by exposure). Walsh, in short, is a mother, and her girlish avatar in the next half of the book is the antonym to motherhood—womanhood, domesticity, privacy, responsibility, reality. Her girl blog, updated from 2005 to 2009, mimics the Socratic “couldn’t-help-but-wonder” wonderings of Carrie Bradshaw, the eternal girl of HBO’s Sex and the City. When a literary agent comes knocking, she urges Walsh to “make it personal. … That’s what people care about!” A French glossy profiles Walsh, shaving four years off her age “for the sake of our consumer demographic.” Walsh, a British author based in Dublin, is herself no girl (she is on the other side of fifty), and her ten published books would not, at first blush, be called girlish. She writes about matters of the heart and the private life, but through measured and sly refraction; thinkers like Barthes and Freud help her work through her moods and memories. In her best-known volumes Hotel (2015), Break.up (2018) and My Life as a Godard Movie (2021), she measures gradations of melancholy and liberation while loitering in bars, messaging an inconstant lover, walking the streets of Paris in the right clothes, checking into faux-grand Art Deco hotels. Her travelogues morph into thought experiments, her philosophical ruminations take in diary entries. That is to say, Walsh is an esoteric confessionalist. She would keep the company of Maggie Nelson, Chris Kraus and other Semiotext(e) types mixing criticism and confession, if she herself were not so autobiographically minimalist. She dispenses personal details like acupuncture needles: pointedly, sparingly, displaced and somewhat mystifying. Of a marriage that ended, she summarizes: “unhappily married (two words to stand in for so much).” Working within the shades of, if not anonymity, then certainly non-celebrity, Walsh is somewhat of a rara avis among self-flaunting autofiction writers. Echoing Rachel Cusk in the Outline trilogy and Elena Ferrante in the Neapolitan novels, she writes in Girl Online, “I’ve always had this thing about disappearing.” But if Walsh is laconic about herself, it is not in concealment but in deference to broader interests, curiosities, possibilities. As Walsh tells it, this eclectic style comes out of—however unlikely—the renaissance of girlie culture in the early internet days. Chick lit, Walsh writes in Girl Online, was then in the process of supplanting the “shock of the new” with the “annoyance of the cute.” This was the time of Emily Gould’s Gawker, of “blog-novels” by Marie Calloway and Catherine Sanderson, of the “semi-amateur First-Person Industrial Complex that paid mostly women writers mostly very little—and sometimes nothing at all—for everything they’d got.” Internet feminists spammed selfies and “overshared,” brandishing their bodies and woes to, apparently, expose the conditions of their degradation. Tumblr, LiveJournal and Blogspot were the places to be a girl indelicately wasting time online. No one was on Twitter yet and it would have been a red flag if you had a Facebook account but weren’t in college. “White, able-bodied, not quite old enough for the screen to entirely refuse my face,” Walsh writes, “I superficially resemble the images of girls that slipped from big screen to small, to digital, their functions carried over as the faces of a brand, a generation, a revolution.” Walsh’s digital genesis begins with a name change—not a reversion to a maiden name, but a new name that started with @. “It was like Adam naming the animals,” Walsh trills. “The first thing we knew from the names was: everyone had a story. Like everyone had a novel inside them and everyone was a star!” On either side of that exclamation point resides the double void of banality and sentimentality, while the introductory “like” works to grind down any strong assertion or delineation. It is the exuberant language of the girl, and sections of the book descends into a hilarious, brilliant girl speak. In another exclamation-riddled chapter, Walsh deadpans/chirps that the reader should forget Wages for Housework—cash in on #theoryplushouseworktheory!. In #theoryplushouseworktheory! you perform “a household, care or personal-upkeep task while reading, listening to or watching works relating to theory and theorists that are freely available online.” Ironing is an ideal activity for #theoryplushouseworktheory! (Walsh recommends to the jazzy tune of Of Grammatology). In a later essay, searching a W. H. Auden quote, Walsh discovers a poem in the “people also ask” results, including the line, “How do you make dip with nothing?” She schleps tote bags—is there a more girlish accessory than a tote with its crumb-encrusted inner seam?—branded, she notes, with “a speech act that hopes to bring about a fit not between world and content but between wearer and world.” She writes in a Dickinsonian aside, “Sometimes, like anyone else, I google myself to find out who I am.” The obvious breaches of good taste and decorum, ironical whimsies and freedoms thrill Walsh initially. “A girl can hammer herself thin as gold leaf until she occupies the whole dimensions of cyberspace,” she writes in a rush. The girl is “elegant and short, like a tweet,” “lovely, like Instagram,” “knowing, like a meme” and “endless, like a comments thread.” “It was amazing to be a thing, an object, a girl,” freed from the constraints of her offline womanhood. And becoming one of the girls was so easy: one merely dispensed with emotional reticence and expanded the “I” infinitely—like Whitman, but bubblier. Instead of raising the individual to a transcendent viewpoint or democratic vista, the girl cashed in on her solipsism, her particularity, her “story.” She alone, she might discover, had an original relation to the universe. In fact, the signature feature of being a girl online, Walsh observes, is the sham guardedness of the girlhood diary—the ease with which the diary’s made-in-China gilded lock might be broken to reveal the neat cursive secrets inside. The girl ultimately resolves inner complexity not through introspection but though coy, knowing self-exposure. More generously put, the girl traffics in artifice, irony, affect, attention—a familiar enough terrain for some artists. And by the end of her book, Walsh indeed breathlessly praises the girl for carrying within her the potential for “the first true amateur work of art.” ● Is this all a spoof? One can almost discern a modern Romantic tradition taking shape—Rousseau’s Emile, Twain’s Huck Finn, James’s children and Emerson’s enthralled eyeball all potential precursors to Walsh’s voicey girls. But isn’t there something a bit off-putting, if instantly recognizable or even self-recognizable, about girl-women as a social type today? In the pre-social media world of 1997, Chris Kraus, chief literary advocate of “lonely girl phenomenology,” noted that “the sheer fact of women talking, being, paradoxical, inexplicable, flip, self-destructive but above all else public is the most revolutionary thing in the world.” As the “personal” came to form the chorus of ambient chatty narcissism on social media, however—introspection and self-promotion, “politics” and profit, one and the same—it became unclear how politically transformative being public online has been for women of the 21st century. The various Obama-era tropes of girls—#girlbosses, Girls Who Code, Wall Street’s “Fearless Girl”—did not attest to the dispersal of radical politics into a world of countercultural idealism. “Girls” heralded just one more new populist front, like another keyword of the Obama era: the hammy “folks” the president evoked alongside a technocratic language, noted by David Bromwich in the London Review of Books, of “critiques” and “trend lines” and “incentivizing.” Likewise, “girls” in the late 2000s and early 2010s typically paid lip service to a lowest-common-denominator solidarity, while aggressively sponsoring a racket of individual economic gain. In 2023, the harms of gender norms and self-objectification are too obvious to adumbrate. But Walsh herself isn’t so dim as to think women don’t also collude in their girlish predicament. “I write about the economic situation of the writer and the things you have to do in order to sustain our practice,” Walsh explained last year in an interview with the Sunday Times. “Girls” must have had something to gain in refusing to call themselves women. Maybe “girlhood” online in the aughts protected women from a culture that subjects women to unfair terms of sexual obsolescence. But maybe it also offered new and indispensable forms of irony, artistic playfulness and experimentation women would otherwise lack. Today it has also made possible something else as well, the injuries of class and power of the “girls” on the New York writing scene: the daughters of the high-finance bigwig, media exec or white-shoe law-firm partner. Backed by capital, they are “freelancing” from Prospect Heights, while luxuriating on Twitter about every facet of their girliness, life an endless girls’ night out, a never-ending sweet sixteen. And so, meet the girl: aesthetically, the “face of the revolution”; commercially, the “face of a brand” that can hide harsher economic facts. It is ultimately the girl’s flickering, ambiguous image that makes her so tricky to judge as a cultural artifact, and perhaps why recent internet novels starring girls online by Lauren Oyler and Patricia Lockwood have been so critically polarizing. Walsh (and we ourselves) might feel as attracted to the winking girlish artifice, as much as we are repelled by the girlish egoism and overexposure that sells so well. (Walsh complains, “I am very tired of using my self as an example,” and reports that the corny confessionalism inflicts her with nausea.) In Girl Online, Walsh can forecast a girl-artist revolution all she wants, but almost in acknowledgment of the rummaging emptiness where higher thought and feeling ought to have been, the narrator herself declines to sell her blog as a novel in the 2000s. ● Elsewhere Walsh has noted the social determinants of all this girlish mystification. The publishing industry and literary world are in part to blame, she has said, conferring as they do special artistic and intellectual privilege upon the young: debut-novel coronation ceremonies in the paper of record, prize-entry age restrictions, books promoted with nail-polish sweepstakes. The issue of ageism multiplies into the issues of sexism, classism, racism. “Why must the ‘best new writers’ always be under 40?” Walsh hammered in a 2014 op-ed: What about the writers who are slowed down because they have to do a day job? What about the authors (mainly women) whose writing time is interrupted for long periods by care for children, or relatives? What about those writers who take years unshackling themselves from backgrounds that make writing seem an impossible dream? Such obstacles, some might venture, might be overcome by logging on, posting, building a brand. But the hope that being a girl online could redress social invisibility—not to mention our cultural bias against age, and particularly aging women—seems naïve at best, glib and cruel at worst. As Sontag once recommended all the way back in 1972: “Instead of being girls, girls as long as possible, who then age humiliatingly into middle-aged women and then obscenely into old women, they can become women much earlier.” Anything less, she added, makes a woman “an accomplice in her own underdevelopment as a human being.” But it is not always clear that what we are seeking online is to be full human beings, certainly not full women. Which might be the more cynical observation at the core of Walsh’s exuberant book.

|

|

|

|

Some Guy TT posted:For a fleeting moment in 2021, Senator Richard Blumenthal traded away his blue suit and American-flag lapel pin. The stiff-backed, deep-pocketed Democratic lion of Stamford, Connecticut took to posing instead as… an unsupervised thirteen-year-old searching for dieting tips on Instagram: just another girl online. Recent Facebook leaks had revealed the netherworld of teen girls sacrificed to the platform’s beasts—psychoses, addictions, cruelties. Who would rescue the girls from the algorithms? The senator may have falsely claimed to have done a tour in Vietnam, but now he was facing real danger, putting himself in harm’s and lechers’ and advertisers’ way to come out on the other end with a solemn briefing for the American people: Silicon Valley whizzes were turning girls into itchy phone addicts and anorexics. The platform’s recommendation pages “latch on to a person’s insecurities, a young woman’s vulnerabilities about their bodies and drag them into dark places,” the senator pronounced, a Pericles for the online age. “Will you commit to ending Finsta?” he probed at a Facebook Senate hearing.

|

|

|

|

War and Pieces posted:call me nostalgic but I think we could use some good old fashioned man-hating harpies They're called terfs now

|

|

|

|

Join my chapter of CERFs today

|

|

|

|

tokin opposition posted:Join my chapter of CERFs today Vint TERF, inventor of the internet

|

|

|

|

Some Guy TT posted:For a fleeting moment in 2021, Senator Richard Blumenthal traded away his blue suit and American-flag lapel pin. The stiff-backed, deep-pocketed Democratic lion of Stamford, Connecticut took to posing instead as… an unsupervised thirteen-year-old searching for dieting tips on Instagram: just another girl online. Recent Facebook leaks had revealed the netherworld of teen girls sacrificed to the platform’s beasts—psychoses, addictions, cruelties. Who would rescue the girls from the algorithms? The senator may have falsely claimed to have done a tour in Vietnam, but now he was facing real danger, putting himself in harm’s and lechers’ and advertisers’ way to come out on the other end with a solemn briefing for the American people: Silicon Valley whizzes were turning girls into itchy phone addicts and anorexics. The platform’s recommendation pages “latch on to a person’s insecurities, a young woman’s vulnerabilities about their bodies and drag them into dark places,” the senator pronounced, a Pericles for the online age. “Will you commit to ending Finsta?” he probed at a Facebook Senate hearing. much to consider!

|

|

|

|

https://twitter.com/TheBaddestMitch/status/1635741828774346752

|

|

|

|

Early on in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, his autobiographical account of New York’s gay cruising scene in the 1970s and 80s, Samuel R. Delany takes his lesbian friend, Ana, to one of the porn theaters that then lined 42nd street. Ana had been intrigued by Delany’s description of anonymous gay sex in the theaters, and reading his book, I get why she wanted to go. Delany writes like he’s composing a eulogy for a lost utopia. In Delany’s mind, the old Times Square offered a democratization of sexuality, a kind of loving that was momentarily unburdened by anxieties of performance or status. But the gay cruising scene of that era was also unburdened, we should note, by the reality of sex inequality. Ana comes with Delany to a theater, and they stay for about an hour, Ana mostly watching. When they leave and walk out into the bright afternoon, Ana recounts a few exchanges she had inside. Men had issued occasional insults and backhanded comments, the sort of thing meant to make her aware that she was a woman in a place for men. One passerby called her “fish.” Maleness served as both armor and passport in this world of sexual freedom, and Ana has neither. But Ana also seems surprised, by the fact that among the men, the atmosphere was overwhelmingly calm and civil, even polite. She recounts turning down a man who had propositioned her in an aisle, only to have him shrug, and smilingly walk away—without recrimination, or threat, or evident resentment. “’You didn’t tell me …’ She paused. ‘Didn’t tell you what?’ “—that so many people say no. And that everybody pretty much goes along with it.’” This is the part that seems so foreign to a woman’s experience: that sexual pleasure might be simultaneously available and also refusable. But for the all the theater scene’s potential, to Ana, it still feels out of reach. “’Would you go again?’” Delany asks her. “‘No.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘Well … I was scared to death!’” Delany chafes at this. Why not? What’s she so afraid of? He doesn’t want to see the difference between them, doesn’t want to admit that there is a difference. But of course women can't cruise—not with anything like the casualness and gamely curiosity that men do. Women have to worry about rape. I think of this scene from Delany often, explicitly for this exchange: The woman, bearing witness to male sexual license, both admires its freedom, and knows that it is not available to her. This knowledge of circumscribed sexual possibilities provokes a range of feelings in women, from rage and shame to jealousy, resentment, obsession, striving, and grief. The problem of how women can pursue sexual life, in a world where sex is so often used to punish and control them, remains something that even the most gifted and intrepid writers on women’s lives find difficult to understand, perhaps even more difficult to tell the truth about. Maybe it’s because so many of these feelings are ambivalent and incriminating. After all, in so much of sexual politics, women are permitted to say only two things about sex: yes or no. One of the writers who has failed to tell the truth about women’s frustrations with sexuality is Louise Perry, in her new book Against the Sexual Revolution. Despite the title, the book dwells very little on the 1960s. Instead, the book is quite narrowly contemporary, with Perry identifying what she feels are problems of modern sexual culture. Perry, a young Brit who writes for places like the Daily Mail, presents herself as a kind of convert, someone who once held Ana’s optimism and yearning for an anonymous and unburdened sexuality, but has since come to see sexual utopia as a childish fairy tale. Now, she believes that the untethering of women’s sexual life from marriage, monogamy, and procreation has been a disastrous mistake, an ultimately doomed project that was undertaken by naïve feminists under the delusional premise that women, contrary to their nature, could “have sex like men.” Much of her book is an attempt to debunk that premise. If the question of how to pursue sexual life under patriarchy is a problem for women, then the solution, in Perry’s mind, is not for women to embark on a feminist effort to change bad conditions, but instead to accept them as unchangeable. Things can’t be otherwise, she insists; women need to seek out the greatest possible protection they can find under a sexual regime of male domination. To this end, she instructs young women to pursue a return to heterosexual marriage, the strategic postponement of intercourse, the abandonment of prostitution and pornography, and the cultivation of sexual “repression” (her word) in men. A digressive thought exercise about whether or not transgender children should be allowed to play school sports arrives with the grim predictability of an algorithm. But Perry’s book might be useful as a measure of the discontent with sex positivity, the sense that feminism’s most well-worn prescriptions for women’s sexual freedom are a bit simplistic—perhaps overly deferential to men’s interests, or too convenient for the status quo. Perry’s objections to sex positivity are not even wrong. She finds understandable discomfort in the proliferation of online porn—particularly the violent kind, which she fears is inculcating men to fetishize hurting women. She is alarmed by what she claims is the ubiquitous popularity of strangulation as a sex act. She points out the degradations and bad pay in much of the sex industry, and calls out feminists for ignoring them. These, at least, are fair criticisms, and at times Perry can be incisive in her diagnosis of feminism’s fears and failures under the sex positivity regime. It is true that porn and its influence has been insufficiently analyzed by a feminism afraid to critique it. It is true that much of feminism has treated sex workers as a monolith, ignoring the industry’s exploitations so as to not seem puritanical. It is true that kinks that eroticize women’s subordinate social position also reenforce and entrench that subordinate social position. It is all true. But if Perry’s diagnoses often seem reasonable, her prescriptions are backward, bizarre. I read Perry’s book recently at the invitation of a friend, who wanted to know what I thought of it. I can see why Perry’s work brought me to mind for her. Against the Sexual Revolution diagnoses some of the same problems I’ve seen, in my own work, with so-called “sex positivity,”—a complicated and contingent phrase, but one which broadly serves to describe the dominant position of feminist sex politics since the second wave era. Sex positivity began as an appropriate phase in feminism’s intellectual maturation. That sex was per se good, and should be treated as a social good, seemed like both the lesson of the ‘60s sexual revolution—with its long-overdue disposal of moralistic, sexist, and retrograde gender codes; and also the correct retort to the ‘80s era of conservative reaction—particularly its cold, judgmental, and murderous condemnation of gay men in the AIDS crisis. Hegemonic forces opposed sexual pleasure, then; sex positivity was a useful rubric for resisting them. But as sexuality became less inhibited in the 21st century, sex positivity lost some of its usefulness as a corrective. In a context of already destigmatized and open heterosexual expression, sex positive thinking could begin to look like a mandate towards women’s sexual availability; not a defense of women’s sexual freedom but a reassertion of men’s sexual entitlement. This was unsustainable; there was always going to be a turn away from sex positivity in feminist thought. But some form of it was a prerequisite in feminist circles from about 1982—the year of the Barnard Conference on Sexuality that ignited the infamous Sex Wars—until 2017, and the mainstreaming of Me Too. Even now, the dominance of sex positivity has only begun to crack. But Perry’s problem with sexuality is not coercion or force; her problem, she says, is “disenchantment.” Perry has an array of culprits for this “disenchantment.” Sometimes men are sexually violent because they are naturally hard-wired to be, by evolution; at other times, they are sexually violent because exploitative tech and porn industries have corrupted and addicted them, making them unable to control themselves. Never does men’s sexual aggression or opportunism seem to be their own fault. Women, too, are wrong about their own professed desires. For a book that’s supposedly so much about the gendered pitfalls of sexual permissiveness, Against the Sexual Revolution spends almost no time on Me Too. When Perry does turn to the movement, she trots out an old misogynist trope: that women who claim to have been sexually violated are really complaining about their own unrequited love. “There were a lot of women who described sexual encounters that were technically consensual but nevertheless left them feeling terrible,” Perry asserts, “because they were being asked to treat as meaningless something that they felt to be meaningful.” But this misunderstands Me Too’s central complaint. The problem was never that women found sex too casual; it was that they found it too unkind. Courtesy, attentiveness, respect for refusal, an investment in someone else’s good time—these are what I hear women looking for in their sexual utopias, and none of them require a diamond ring. The problem expressed in much of Me Too was not that committed straight love was too hard to come by. It was that sex had become much more available, but it had not become more refusable. If Ana was scared in the movie theater, it’s easy to imagine Perry as an enthusiastic scold, interrupting the furtive blow jobs in the rows of seats to tell the patrons to stop deluding themselves, and admit that what they really want is to settle down and get married. “I am critical of any ideology that fails to balance freedom against other values,” Perry writes. What other values? She doesn’t say. Part of why Perry’s book seems like a wasted opportunity is that other writers have engaged with the failures and inadequacies of sex positivity in much more productive terms. In the years since Me Too, there has been a groundswell of feminist writing that grapples with the social and political dimensions of sexual dominance in ways that are braver and more truthful than what might have been possible back when sex positivity went unchallenged. Books by lucid, compelling, and often productively uncertain writers have emerged: I’m thinking of Amia Srinivasan’s The Right to Sex, and Lorna Bracewell’s Why We Lost the Sex Wars. Christine Emba’s Rethinking Sex is an idiosyncratic critique of sex positivity on both radical feminist and Christian theological grounds. Nona Willis Aronowitz, the daughter of the influential sex-positive feminist Ellen Willis, has written a surprisingly emotionally honest book, Bad Sex, which mixes memoir with feminist history to examine how, and whether, her mother’s ideas are applicable to her own life. These writers are drawing on a long history of feminist critiques of the sexual revolution, critiques that examine men’s sexual opportunism and force without ceding women’s claims to freedom, or denouncing sexuality’s utopian potential. There’s the incendiary Andrea Dworkin, or the compassionate visionary Audre Lorde, or the singular genius Catherine MacKinnon. Few of these women would agree with each other, but all of them take positions that could be called sex-negative. None of them accept sexual inequality as inevitable. Conservatives like Perry, by comparison, don’t seem alert to sex’s pleasure or potential at all; they don’t seem to really think that much of value is lost, or violated, in sexual violence. But I guess this makes sense. If you think of the whole sexual sphere of life as corrupt and degraded, full of broken delusions and corrupting vanities, then rape, or coercion, or any of the other kinds of sexual cruelties that men inflict on women, might not seem so terrible. They’re not an insult to what sex could be, but merely the logical conclusion of what it always has been. But for all Perry’s cynicism, it seems like we may be returning to the kind of world she would prefer. A creepy, tech-savvy version of gender conservatism among women is gaining ground. Social media is awash with clips of tradwives and “stay-at-home girlfriends,” performing a choreographed pantomime of hyper-stylized 50s femininity, including cooking and waiting for men to come home. Peter Thiel is bankrolling a women’s media company, “Evie,” that advocates for gender “complementarianism.” Like Perry, they issue dark warnings about hormonal birth control. Roe is gone, and abortion has been outlawed in large swaths of the country; unless something dramatic changes in American politics, a national abortion ban, and the rollback of contraceptive rights, are coming, too. It’s possible that no woman has ever had real access to sexual utopia. It’s possible that all of them, like Ana, have found that exposure to absolute sexual freedom, such as it exists under patriarchy, often leaves them alienated and scared. In that sense, sex positivity may have always been inadequate, partial, a fantasy. But it seems tragic to give up the progress we’ve made, and cowardly to abandon the fight. Maybe sex positivity was always fake. But I think we’ll miss it when it’s gone.

|

|

|

|

This is what the Vampire's Castle does to ya. When it looks like change might require imagination and effort, give up and run away crying.

|

|

|

|

We're at pussy phrenology, people https://twitter.com/ryanlcooper/status/1640062569082658820?t=s0fxFR8vkvlYfv3yGbpF2w&s=19

|

|

|

|

im struggling to figure out what possible context could have led to this argument

|

|

|

|

Some Guy TT posted:im struggling to figure out what possible context could have led to this argument You live a very boring life I suppose

|

|

|

|

Some Guy TT posted:im struggling to figure out what possible context could have led to this argument Terf thinks trans womens genitals are "mutilated", cis women point out that theirs look very similar to trans women, and this unhinged weirdo is currently losing it on twitter lmao

|

|

|

|

Some Guy TT posted:im struggling to figure out what possible context could have led to this argument There was an art project with a bunch of plaster pussies, and some idiot circled the ones that belonged to “real women”. e: Oh OK the pussy (coward) vagina (pussy) phrenologist deleted it. It was this.  for ghostly white disembodied vulvæ for ghostly white disembodied vulvæ

Platystemon has issued a correction as of 22:23 on Mar 26, 2023 |

|

|

|

Also it's not that her vulva looks similar to that of a trans woman, but just that it looks similar to one of several that the terf decided was trans.

|

|

|

|

Dr. Stab posted:Also it's not that her vulva looks similar to that of a trans woman, but just that it looks similar to one of several that the terf decided was trans. She's currently asking people for pictures of their vulva

|

|

|

|

It’s the crossover of the “debate me” and “PM me pics” obnoxious Internet commenter types that we didn’t know we needed.

|

|

|

|

sounds to me like we need a vagina inspector wasnt there one here a minute ago he was wearing a shirt that said vagina inspector on it

|

|

|

|

apparently she was pressured into a genital surgery she regrets and it broke her to the point where she is on a lifelong crusade against all vulvas she decides aren't natural

|

|

|

|

wtfs a vulva

|

|

|

|

AnimeIsTrash posted:wtfs a vulva it's a car, which you love to post about

|

|

|

|

AnimeIsTrash posted:wtfs a vulva It’s a plastic trumpet that fans blow at football matches in South Africa, but that’s not important right now.

|

|

|

|

https://twitter.com/BadWritingTakes/status/1640064966601461762?t=0KEIR9pnUZr13O_UtGrYAw&s=19

|

|

|

|

loquacius posted:https://twitter.com/BadWritingTakes/status/1640064966601461762?t=0KEIR9pnUZr13O_UtGrYAw&s=19

|

|

|

|

Rowling loves to straight up gaslight people about what she’s written. Like she says that she never explicitly described Hermione as having white skin, but she totally did.

|

|

|

|

Hermione is a minstrel character whose blackface gets replaced by film negatives upon seeing a ghost

|

|

|

|

Platystemon posted:Rowling loves to straight up gaslight people about what she’s written.

|

|

|

|

tbf someones face going white just means they go pale with fear or whatever verdict: inconclusive, black hermione could still be canon

|

|

|

|

It does make everyone's dismissal of her hatred of slavery all the worse.

|

|

|

|

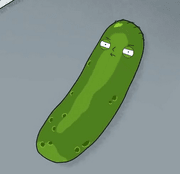

she's insisted that the big snake was always meant to have been a korean woman under a curse i don't think she remembers that the last line of Harry Potter is him wondering if his inherited slave will make him a sandwich, either

|

|

|

|

still lolling at the thing about the podcast name like, are we to understand that the name was chosen entirely at random and was not meant to refer to any particular person being subjected to a witch trial? Why???

|

|

|

|

loquacius posted:still lolling at the thing about the podcast name Just replace anti-semite with terf -

|

|

|

|

https://twitter.com/deportablediz/status/1640271724984819713

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Posting TERF art A Buttery Pastry posted:Ever heard of vitiligo??? Maybe only her face is white. Also her left hand  War and Pieces posted:Hermione is a minstrel character whose blackface gets replaced by film negatives upon seeing a ghost You are a RACIST for comparing this to a minstrel character, and you have given Joanne a great deal of difficulty. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/jun/05/jk-rowling-harry-potter-cursed-child-jack-thorne-john-tiffany-interview posted:I had a bunch of racists telling me that because Hermione ‘turned white’ – that is, lost colour from her face after a shock – that she must be a white woman, which I have a great deal of difficulty with. But I decided not to get too agitated about it and simply state quite firmly that Hermione can be a black woman with my absolute blessing and enthusiasm. but also she turns “faintly pink” sometimes quote:"I love you, Hermione," said Ron, sinking back in his chair, rubbing his eyes wearily. Hermione turned faintly pink, but merely said, "Don't let Lavender hear you saying that." And when she gets a black eye, quote:Hermione sitting at the kitchen table in great agitation, while Mrs. Weasley tried to lessen her resemblance to half a panda. Maybe it’s a dyed panda.

|

|

|

|

I remember Animorphs

|

|

|

|

Wombyn

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Jun 7, 2024 07:57 |

|

avoid the noid

|

|

|