|

RealityWarCriminal posted:the river i was going to drink that water e: i realize the river is where montreal puts their sewage, so probably just a bad idea all round infernal machines has issued a correction as of 03:16 on Aug 18, 2023 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 27, 2024 16:24 |

|

From A Profusion of Spires: Religion in Nineteenth-Century Ontario "Can we also trace back to the last century the origins of the secularizing tendency that has led twentieth-century Ontarians in increasing numbers to abandon religious practices that were once almost universal? With hindsight we find it natural to interpret any signs of confusion or doubt as evidence of decline, and undoubtedly the facade of ecclesiastical triumphalism concealed some cracks in the plaster and even weaknesses in the construction. That there was any overall falling off in religious commitment, however, is a conclusion for which it is difficult to produce solid evidence. It seems more to the point to note that industrialization and urbanization, which had already had a weakening effect on religious structures in countries with more mature economies, were significantly present in Ontario as well. The shift from organic to mass societies, replacing coherent communities with combinations of atomistic individuals, was probably, in the long run, more corrosive of religious commitment than any of the specific questions with which the churches had to wrestle in the late nineteenth century. More satisfactory answers might have been given to these questions, but there is no great reason to think that many more people would be going to church today if they had. Social developments over which the churches had little control, rather than their response to them, were the most significant precursors of twentieth- century secularization." "To note such continuities is not to deny that history contains elements of surprise and unpredictability. Many developments of the twentiethcentury could scarcely have been foreseen by the most far-sighted observers of the religious situation as it was in 1900, for nothing in previous experience suggested them. To have informed an Ontarian of the late nineteenth century that before another century had run its course Islam and religions from farther east would have a significant place in the provincial spectrum, that Louis Riel would become a popular hero, that local theologians would take their cues from Latin America as readily as from Europe, that apologies would be offered to the native peoples for the missionaries' paternalism, or that churches would devote more attention to the rights of homosexuals than to the wrongs of alcohol would merely have been to invite incredulity." "Readers are likely to ask whether, among the characteristic features of nineteenth-century religion, there were any that can be identified as distinctively Ontarian. They need not expect too much. In its main outlines the story of Ontario religion in the nineteenth century was a miniature version of the general religious history of the era. Assumptions about religion prevalent in the province were those familiar in other English- speaking areas: belief in a providential order that came to look more and more like human progress or biological evolution, a close linkage between religious belief and personal morality, a frequent confusion between faith and sentiment, an expectation that religious conviction should issue in participation in a variety of voluntary activities, and, not least, the importance of being earnest. Religious impulses affecting the province were also almost invariably imported. The evangelical united front, mid-century movements that reasserted the primacy of spiritual over temporal authority, devotional practices from Ireland, French Canada, and American holiness circles all had local repercussions. In this respect Ontario showed less initiative than the maritime provinces. Whereas Henry Alline stirred great excitement there with a highly original message, the Methodists who had had equivalent success in Upper Canada disclaimed any intention of introducing doctrinal novelty." "Similarly, the religious problems faced by Ontarians were essentially those of Western Christendom. The proper relations of church and state, of faith and science, and of capital and labour were all live issues elsewhere before they were discussed in Ontario, and local debates were conducted mainly with borrowed arguments. Even the difficulties of extending religious institutions to the unreached, which attracted so much attention in the early decades of the province's history, were well understood by religious workers in the slums of Glasgow or by black preachers in the southern United States. This derivative quality need occasion no surprise. Throughout the nineteenth century imported clergy were both numerous and prominent, and British and American books, tracts, and periodicals circulated freely. Only after mid-century did a heterogeneous immigrant population coalesce into a coherent populace. If we seek to identify distinctive elements in Ontario religious history, therefore, we must content ourselves with variations in emphasis and differences in outcome." "The basic ingredients of a cake are flour, sugar, and shortening, with a dash of soda or baking-powder to make it rise, but its texture and flavour will vary enormously according to the proportions used. Similarly, the religious character of a region can vary with the ecclesiastical mix. In continental Europe it has been normal for state churches to provide for the religious needs of the bulk of the population, leaving the dissatisfied to find spiritual homes in conventicles that cultivate a more strenuous piety. Ernst Troeltsch formulated the dichotomy of church and sect to draw sharp contrasts between the two. In the United States, a wide range of ecclesiastical bodies have long enjoyed equal constitutional rights, and public opinion has accepted an unlimited plurality of churches as normal and natural. Unconvincing attempts have been made to apply Troeltsch's classification to the American situation, but Sidney Mead's concept of 'denominations' sharing the ground and selectively affirming national values fits it much better. The tradition of the British Isles, though it varies somewhat from country to country, has fallen somewhere between the continental and the American. Established churches in England and Scotland, and less effectively in Ireland until disestablishment in 1869, have been at least the intended embodiments of nationally recognized spiritual values. In marked contrast with the continental situation, however, dissenting bodies have in the aggregate rivalled national churches in numbers and sometimes exceeded them in vitality." ... "Nineteenth-century Ontario organized its religious life in ways that suggest obvious parallels with both the United States and Europe. Especially after 1854, resemblances to the American situation were most obvious. The province had no established church, and the only ecclesiasti- cal body that had seriously aspired to this status was neither the largest nor the fastest-growing. The major churches displayed the typical attitudes of the denomination, never more clearly than in their efforts for conservative reform near the end of the century. As in the United States, too, the dominant force was an evangelical Protestantism whose segments worked readily in tandem while insisting on their own peculiarities of belief and practice. In some other respects, however, Ontario reproduced or inclined toward Old World patterns. After the initial turnover of the pioneer period, religious affiliation represented for most Ontarians something inherited rather than something acquired. In comparison with the United States, it leaned toward the traditional end of the denominational spectrum. In the United States Baptists were numerous and Episcopalians an elite minority; in Ontario the Church of England was large and Baptists relatively few. Ontario religious practice, which struck European visitors as informal and sometimes even casual, seemed to Americans restrained and 'churchy.' Resistance to the multiplication of church bodies has also been more suggestive of Europe than of the United States, and hospitality to proposals of church union pointed to a bad conscience about the divisions that already existed." "In some respects the religious moulding of Ontario may not have been greatly different from that of Ohio or Lancashire, but its significance was enhanced when Ontario became the largest, wealthiest, and most strategi- cally located province of a newly emerging nation. The responsibilities thus implied probably did not weigh heavily on the consciences of church members in Petrolia or Smiths Falls, but they could not be ignored by policy-makers and program planners in Toronto. The influence of Confed- eration on Ontario religion was somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, uncertainty with respect to Canada's religious future and especially that of the developing west intensified competition among the churches and encouraged a combative spirit on both sides of the Protestant-Roman Catholic divide. On the other hand, the challenge of meeting the spiritual needs of a scattered and diverse population cast into question the prevailing denominational pattern and was a significant, if not always conscious, spur to the advocacy of church union. Not by chance did the preamble to the Basis of Union of the United Church of Canada commit it 'to foster the spirit of unity in the hope that this sentiment of unity may in due time, so far as Canada is concerned, take shape in a Church which may fittingly be described as national.' The framers did not have in mind an establishment on Old World lines, but they were certainly projecting something other than the American denominational system. Not by chance, either, did this vision meet its greatest resistance in Ontario." This combination of ecclesiastical, demographic, and historical factors gave rise to a religious tradition that was not quite duplicated elsewhere. One is tempted to apply an analogy from economic organization. Religion might be described in continental Europe as a state monopoly with marginal provision for individual initiative, in the United States as a field for unbridled free enterprise, and in Britain as a class structure with some fluidity at the edges; in this context we might think of Ontario as preferring a typically Canadian mixed economy. One might also identify elements of the limited sovereignties for which Harold Laski argued. Religious institutions neither controlled nor were controlled by the apparatus of the state, but neither were they relegated altogether to the private realm. After 1854 they were all private corporations in law, but in matters of morality and education their public standing received practical recognition. ... "That many of the landmarks so carefully established in the nineteenth century have fallen into serious disrepair in the twentieth is scarcely open to question, although it is only necessary to reopen the separate-school issue or propose a relaxation of restrictions on Sunday business to discover that the convictions responsible for their erection are by no means dead. The hopes that inspired many Ontarians to anticipate the speedy advent of the Kingdom of God are not patently closer to fruition. Cracks in the structure of belief that began to open before the turn of the twentieth century have widened in the interim. Restraints that were expected to hasten the emergence of a new and higher type of humanity are now derided as evidence of the province's cultural backwardness. Church-going is not what it was when the Globe conducted its surveys, and the new religiosity touted in the 1960's has not yet shown signs of providing a substitute. Many Ontarians still seek to be faithful to religiously inspired visions of the cosmos, although the religious systems that inspire them are of a variety that would have startled their nineteenth-century predecessors." "The last word, however, belongs to those who surveyed nineteenth- century religion at close range. When religious journals greeted the advent of the twentieth century, they inevitably used the occasion to publish appraisals of the past and prognostications for the future. Most were distinctly positive in tone. Nathanael Burwash, reviewing a recent survey of nineteenth-century theology, asserted that after three generations of 'running the gauntlet of ... pantheism, materialism, and historical criticism' the world had come to 'a truer, stronger, and more universal faith in Christianity.' James H. Coyne, after summarizing progress in various secular fields, concluded by 'affirming that the mental, moral and religious outlook [had] never been so bright, so clear, so full of hope for the future, as in the closing years of the century.' The Westminster, looking back on a century 'of marvellous progress in every direction,' noted reports from far and near of 'quickened desire and awakened hope' and concluded that the church had 'scarcely touched the fringe of her possibilities.' The Catholic Register, for once agreeing with its Protestant rivals, was thankful that religion had been 'full of faith and activity in this wonderful century' and felt confident that the one then beginning would 'present to history a record of noble zeal and high intellectual culture.' Only the Canadian Churchman viewed the incoming century with alarm, predicting with at least partial prescience that without a radical change in customs and laws 'the race we are now proud of would give way to' another, with more faith in God and His promises.' While most other forecasts avoided extremes of cocksure- ness and despair, the prevailing mood at the turn of the century was one of thankfulness for the past and optimism for the future." Frosted Flake has issued a correction as of 03:34 on Aug 18, 2023 |

|

|

|

K

|

|

|

|

Frosted Flake posted:From A Profusion of Spires: Religion in Nineteenth-Century Ontario nice meltdown

|

|

|

|

Here's a trick to absorb long(-winded) texts efficiently: just read the first and last sentence of each paragraph. "Can we also trace back to the last century the origins of the secularizing tendency that has led twentieth-century Ontarians in increasing numbers to abandon religious practices that were once almost universal? Social developments over which the churches had little control, rather than their response to them, were the most significant precursors of twentieth- century secularization." "To note such continuities is not to deny that history contains elements of surprise and unpredictability. To have informed an Ontarian of the late nineteenth century that before another century had run its course Islam and religions from farther east would have a significant place in the provincial spectrum, that Louis Riel would become a popular hero, that local theologians would take their cues from Latin America as readily as from Europe, that apologies would be offered to the native peoples for the missionaries' paternalism, or that churches would devote more attention to the rights of homosexuals than to the wrongs of alcohol would merely have been to invite incredulity." "Readers are likely to ask whether, among the characteristic features of nineteenth-century religion, there were any that can be identified as distinctively Ontarian. Whereas Henry Alline stirred great excitement there with a highly original message, the Methodists who had had equivalent success in Upper Canada disclaimed any intention of introducing doctrinal novelty." "Similarly, the religious problems faced by Ontarians were essentially those of Western Christendom. If we seek to identify distinctive elements in Ontario religious history, therefore, we must content ourselves with variations in emphasis and differences in outcome." "The basic ingredients of a cake are flour, sugar, and shortening, with a dash of soda or baking-powder to make it rise, but its texture and flavour will vary enormously according to the proportions used. In marked contrast with the continental situation, however, dissenting bodies have in the aggregate rivalled national churches in numbers and sometimes exceeded them in vitality." ... "Nineteenth-century Ontario organized its religious life in ways that suggest obvious parallels with both the United States and Europe. Resistance to the multiplication of church bodies has also been more suggestive of Europe than of the United States, and hospitality to proposals of church union pointed to a bad conscience about the divisions that already existed." "In some respects the religious moulding of Ontario may not have been greatly different from that of Ohio or Lancashire, but its significance was enhanced when Ontario became the largest, wealthiest, and most strategically located province of a newly emerging nation. Not by chance, either, did this vision meet its greatest resistance in Ontario." This combination of ecclesiastical, demographic, and historical factors gave rise to a religious tradition that was not quite duplicated elsewhere. After 1854 they were all private corporations in law, but in matters of morality and education their public standing received practical recognition. ... "That many of the landmarks so carefully established in the nineteenth century have fallen into serious disrepair in the twentieth is scarcely open to question, although it is only necessary to reopen the separate-school issue or propose a relaxation of restrictions on Sunday business to discover that the convictions responsible for their erection are by no means dead. Many Ontarians still seek to be faithful to religiously inspired visions of the cosmos, although the religious systems that inspire them are of a variety that would have startled their nineteenth-century predecessors." "The last word, however, belongs to those who surveyed nineteenth-century religion at close range. While most other forecasts avoided extremes of cocksureness and despair, the prevailing mood at the turn of the century was one of thankfulness for the past and optimism for the future."

|

|

|

|

yellowcar posted:never been there personally and imo northern ontario might as well be its own province curling canada on the right side of history

|

|

|

|

You can then translate it into modern vernacular the way, say, Matt Berry would (this is exhausting): "Why don't Ontarians give a toss about God anymore? It's because Victorians were sexual freaks who couldn't pretend to be shut-in prudes forever." "History is one loving astounding revelation after another. Egerton Ryerson would have shat his britches to know they denounced his educational genocide programme, but at least he'd rest easy knowing that the apologies were nearly as hollow as his defaced statue." "Are the smug pricks in Ontario different from the slack-jawed yokels across the pond? Some bindle-slinging troublemaker named Henry Alline tried preaching original sermons, but they were having none of that - know your place and stick to the bible, you condescending twat." "You have to beat an egg off to make a cake, as I like to say. That's why some like their communion wafers hot, and some - do not."

|

|

|

|

I guess what I'm trying to say is that most organized religion is hosed and the best you can hope for is that your historical churches keep getting converted into luxury lofts instead of demolished for shoebox condos, FF.

|

|

|

Frosted Flake posted:From A Profusion of Spires: Religion in Nineteenth-Century Ontario

|

|

|

|

|

eXXon posted:You can then translate it into modern vernacular the way, say, Matt Berry would (this is exhausting): hey, this one was published in 1988. it's positively contemporary by ff's standards

|

|

|

|

Hot Karl Marx posted:all i know is that london is the worst city in ontario it's true there's even has a song about it

|

|

|

|

They had a pdf rather than microfiche and everything.

|

|

|

|

Frosted Flake posted:They had a pdf rather than microfiche and everything. do you ocr those microfiche or is this all painstaking manual transcription?

|

|

|

|

infernal machines posted:do you ocr those microfiche or is this all painstaking manual transcription? I can usually just send it to the staff at the research centre if I need it for work, but sometimes I have to transcribe it if it's for posting purposes.

|

|

|

|

i honestly admire your dedication to posting

|

|

|

|

Kelowna is also on fire now

|

|

|

|

Things are going to get a lot worse before they, well continue to get worse

|

|

|

|

I would start looking for "Albertan family has their RV vacation ruined" stories like there were during covid restrictions but google doesn't let me read the news anymore

|

|

|

|

my morning jackass posted:there is a united front across religious and cultural lines relating to sexuality and such. in all these anti-lgbtq+ rallies you get quite a diverse group of people. probably individually these groups would have limited visibility or influence outside of their immediate circles, but as a coalition they are able to draw more attention. In fact that smug Canadian exceptionalism blinds people to the threats, as exhibited in this very thread.

|

|

|

|

Saalkin posted:It's Sarina you clowns Who's Sarina?

|

|

|

|

PhilippAchtel posted:Who's Sarina? A city so poo poo that I can't be assed to spell it right. But Sarnia my bad.

|

|

|

|

Sarnia barely makes the bottom 10 median house price list in Ontario. You want a real deal? Move to Timmins.

|

|

|

|

bvj191jgl7bBsqF5m posted:Kelowna is also on fire now Typical.

|

|

|

|

the FIRE to MAID pipeline

|

|

|

|

Magic Hate Ball posted:the FIRE to MAID pipeline

|

|

|

|

Death By The Blues posted:The Durham region has some of the best food in the GTA sans Toronto if you know where to look and the traffic is less dire then other spots so it leaps ahead based on that. London has some of the worst loving drivers in Canada for some strange reason and there is also the racism. Hate that city. yeah I gotta say durham has had some great food joints open up in the last 5 years, especially in whitby/oshawa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

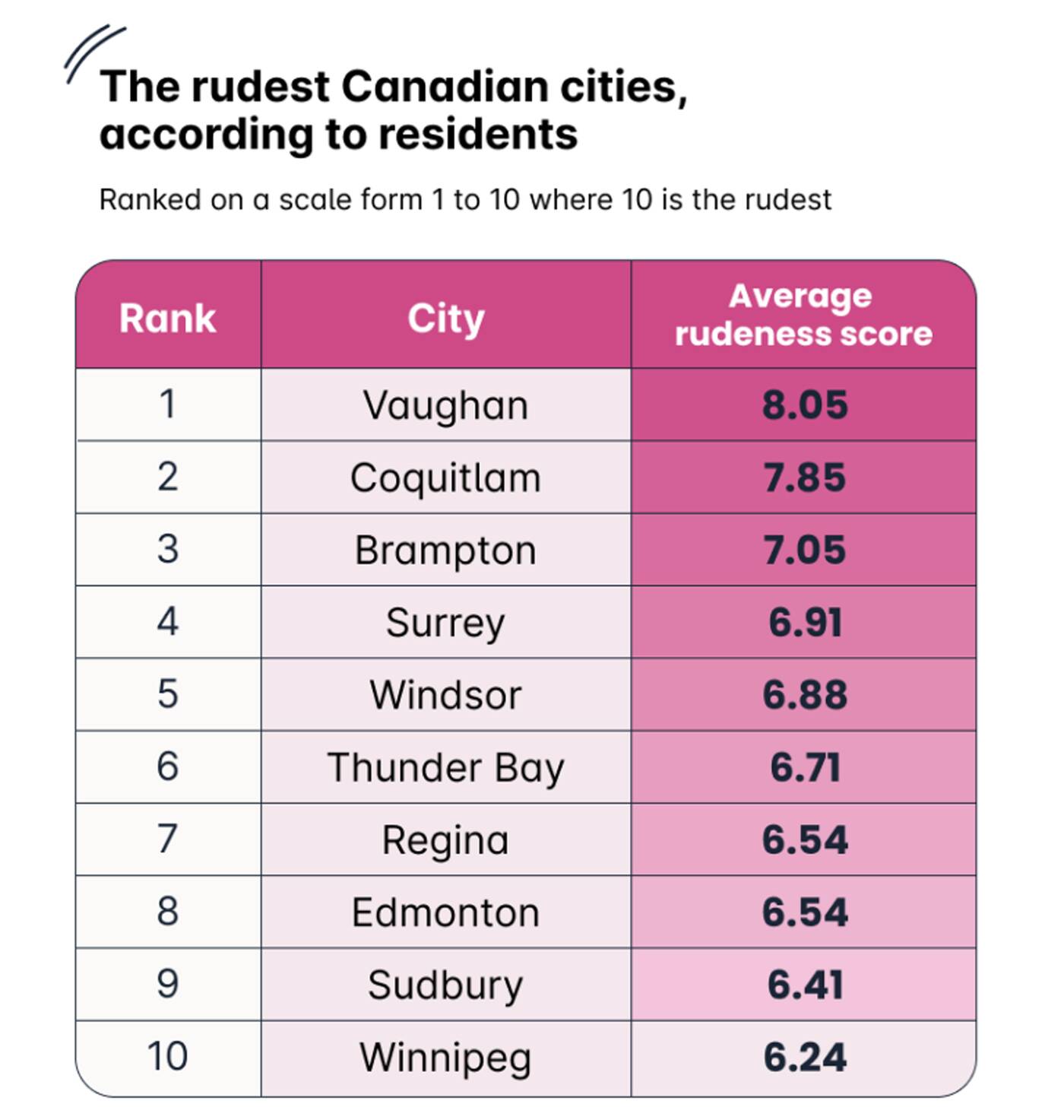

That poll can gently caress off and eat poo poo.

|

|

|

|

wheres the lie

|

|

|

|

where the gently caress is hamilton

|

|

|

|

Arivia posted:where the gently caress is hamilton toronto's not on there either so imagine how bad vaughan must be

|

|

|

|

Where is Red Deer, full of insecure chuds.

|

|

|

|

I feel like given US cultural hegemony it would be a far more productive question to ask how the evangelical Protestants, the types with the massive churches in the suburbs, gained such a foothold in Canada and came to dominate our society. I have a strong suspicion it�s because their view on capitalism and the other fits well with modern neoliberal capitalism, like how Mormonism is the home of MLM

|

|

|

|

the sects of Christianity that call for self sacrifice and humility and honest to God charity work may as well be the Arians for how much they matter to how the church should be seen today

|

|

|

|

what is the methodology

|

|

|

|

|

tuyop posted:what is the methodology biggest rear end holes

|

|

|

|

tuyop posted:what is the methodology https://preply.com/en/blog/rudest-cities-in-canada/

|

|

|

|

lmao

|

|

|

|

CLAM DOWN posted:

Attempted murder of pedestrians on the same level as talking loudly or looking at phone, sounds about right

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 27, 2024 16:24 |

|

that is a nice racism list. top four are where the new immigrants are and the rest where racists are.

|

|

|