- LITERALLY A BIRD

- Sep 27, 2008

-

I knew you were trouble

when you flew in

|

I am just going to copy/paste this whole-rear end post (and its sequel post) in here without revising my commentary because I am just not that ambitious today  I mentioned this paper in here this summer but never ended up getting into it so... here we are! Please forgive the tone of my commentary having more emphasis on modern metaphysics than ancient history, the topic of this paper blurs those lines quite effectively, don't judge me too hard. I mentioned this paper in here this summer but never ended up getting into it so... here we are! Please forgive the tone of my commentary having more emphasis on modern metaphysics than ancient history, the topic of this paper blurs those lines quite effectively, don't judge me too hard.

quote:

well my big problem is they are both paywalled and I don’t have pdfs to share right now (maybe later, when my partner who is the one possessed of a JSTOR login returns home). But I am talking about Edward Karshner’s paper Thought, Utterance, Power: Toward a Rhetoric of Magic and Vincent Tobin’s paper Mytho-Theology in Ancient Egypt (this one is particularly interesting if you pair it with some of the thoughts theologians of modern religions have put out about the importance of myth and symbol in personal life and faith; I am thinking of the corresponding chapter in Paul Tillich’s Dynamics of Faith, particularly. “For there is no substitute for the use of symbols and myths: they are the language of faith.”). While I don’t have pdfs I have some very lovely printouts that I made, on colorful paper so they’re harder for me to lose well my big problem is they are both paywalled and I don’t have pdfs to share right now (maybe later, when my partner who is the one possessed of a JSTOR login returns home). But I am talking about Edward Karshner’s paper Thought, Utterance, Power: Toward a Rhetoric of Magic and Vincent Tobin’s paper Mytho-Theology in Ancient Egypt (this one is particularly interesting if you pair it with some of the thoughts theologians of modern religions have put out about the importance of myth and symbol in personal life and faith; I am thinking of the corresponding chapter in Paul Tillich’s Dynamics of Faith, particularly. “For there is no substitute for the use of symbols and myths: they are the language of faith.”). While I don’t have pdfs I have some very lovely printouts that I made, on colorful paper so they’re harder for me to lose

Here is the abstract for the former:

Thought, Utterance, Power: Toward a Rhetoric of Magic posted: To the ancient mind, magic was a powerful force to be subjected to or to control. Egypt, more than any other early culture, stressed the importance of intellectual agency as the antidote to the imperfection perceived between foundational thinking and anti-foundational speaking. Just as rhetoric seeks to express the conceptual ideal pursued by philosophical inquiry, these earlier thinkers stressed magical language as the key to unlocking the power of the cosmos. This article will explore the Ancient Egyptian concept of rhetorical magic as a practical wisdom that allows an individual to function fully within the boundaries established by a perceived cosmic order. The Ancient Egyptians applied rhetorical magic to ease the dissonance felt between intellectual engagement and the semiotically saturated cosmology in which they dwelt. These same ancient rhetorical practices hold promise in assisting our own attempts to navigate a world inundated with information.

And the latter does not have an abstract but here is an excerpt that can provide a similar function:

Mytho-Theology of Ancient Egypt posted:Egyptian religion was marked by an exceedingly high degree of freedom of belief, and, except for the short-lived Amarna period under the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten, the concept of religious heterodoxy was totally unknown to the Egyptians. All of the symbols and expressions of the various local cults and traditions were regarded as valid and correct expressions of religious faith, and internal contradictions in articulation were seen as both acceptable and natural. Egypt’s complex mythological system has been aptly described as being “completely free of those logics which eliminate one of two contradictory concepts and press religious ideas into a system of dogmas.” [R. Anthes, “Egyptian Theology in the Third Millenium BC,” JNES XVIII (1959) 170.] Such an approach to the content of a religion can only be possible when it is quite obvious that the concrete expressions of that religion are indeed mythic and symbolic in nature and are not intended to be taken as factual dogmatic statements of a literal “truth.” Such a flexible approach to the realm of the spiritual appears to be the most positive feature of the religion of ancient Egypt, for this approach enabled it to encompass virtually any religious symbol as a valid expression of abstract reality.

For the purposes of this post I will focus on the Karshner paper. The Tobin one is a great companion for it but I have such a passion for this Karshner paper. It starts like this:

quote: Going back as far as the Old Kingdom (2450–2300 BCE), ancient Egyptian speculative thinkers had already developed a complex understanding of the relationship between personal agency, power, and the role of magic. What is more, these early philosophers saw that this world (individual and social) and the other (cosmological) operated according to the same principles. The rules by which one secured power were the same whether one was a peasant or a god. Through perception, the heart/mind would design an idea, the mouth would speak it and, as if by magic, the task would be accomplished. Thoughtful, reasoned speech was the mechanism for reestablishing the order that was manifested in the reasoned creation of the universe. Power and magic were not mysterious or esoteric to the Egyptians. Instead, power and magic were a part of an individual’s very existence.

This paper explores the parallel epistemological roles magic and mysticism share with rhetoric and philosophy within the Egyptian metaphysical system.The rhetoric of Egyptian magic was based on the idea that deeper foundational truths were expressed in a highly figurative, mythical language as a means to avoid an antifoundational emphasis on language only. Truth and the expression of truth were not seen as mutually exclusive. Rather, to reconnect with the higher reality of truth, the Egyptians stressed, through the very structure of their complex symbol system, an intense, epistemic interaction with words and symbols as maps to truth— not truth itself.

I further illustrate that the ancient Egyptians understood the dissonance between foundationalist epistemology and antifoundationalist rhetoric. Yet they still believed that within this uncertainty a coherent order was to be found. Magic, operating as an epistemic rhetoric, sought to reconnect the practitioner, through reasoned speech, to the ethical truth of the universal mind. This reconnection was made possible by the ethical epistemology agents gained from a life spent seeking maat (truth) in every given situation. Through the full utilization of magio-rhetoric, an individual could arrange experience in such a way as to express ethical knowledge. Understanding, then, occurred epistemically through the close observation of the cosmos and through an accurate and rational articulation of the knowledge gained from that observation. In short, it was intense individual effort directed toward the apprehension and expression of the seemingly inaccessible realm of the mystical that elevated the profane word to sacred truth in the end.

You’re still with me? You follow this, it seems interesting? Okay, great. Just checking. I have shared this paper with a few friends now and the word “dense” appears in everyone’s reviews  I don’t know if it’s helpful or interesting to keep in mind while reading that while this is a historic/academic paper, it is discussing components of a religion that is extremely real and present and alive for me. I have very much “spent my life seeking ma’at,” and I think this paper is just exceptional in its examination of this aspect of Egyptian religion and metaphysics. I am going to continue directly into the next section, titled “Mysticism as Philosophy: The Foundational Scene of Utterance.” I don’t know if it’s helpful or interesting to keep in mind while reading that while this is a historic/academic paper, it is discussing components of a religion that is extremely real and present and alive for me. I have very much “spent my life seeking ma’at,” and I think this paper is just exceptional in its examination of this aspect of Egyptian religion and metaphysics. I am going to continue directly into the next section, titled “Mysticism as Philosophy: The Foundational Scene of Utterance.”

quote: The most basic assumption of rhetorical discourse is that an utterance is a reaction to a certain exigency, directed toward a particular audience who is seen as being capable of mediating the exigency. This process of mediating disorder through discourse requires that the speaker and audience share a set of philosophical beliefs about a foundational order that is a priori to the recognized ontological order. Philosophy, as the foundational scene of rhetoric, represents a specific kind of knowledge and speaking that comes through close observation of and engagement with the world and other meaning-seeking agents. This experiential knowledge allows speakers to apply, in each case, a set of knowable contexts that not only express their worldview but speak to the specific worldview of the individual or group they hope to persuade. Rhetoric, then, is more than persuasive speech. It is also an expression of a linguistically constructed worldview.

In The Mind of Ancient Egypt, Jan Assman identifies this belief in the relationship between the perception and expression of existence as being characteristic of a “cosmological society.” He writes that a cosmological society “lives by a model of cosmic forms of order, which it transforms into political and social order by means of meticulous observation and performance of rituals” (2002, 205). According to Assman’s definition, a cosmological society creates meaning based on the close observation of foundational forms in a manner that closely references the original forms or order. Assman goes on to explain that meaning emerges from the ability to “adapt the order of the human world to that of the cosmos [and] to keep the cosmic process itself in good working order” (2002, 205). The cosmos itself becomes a heuristic revealing mystical knowledge that establishes the local, personal, and social order at the same time that the local, personal, and social order serves as a heuristic in establishing magical practices that maintain the cosmological order. In other words, while the agent is speaking from a social scene to a human audience, he or she is simultaneously addressing deities in the cosmological realm. The disputants and the discourse, then, speak from and to a complex, multilayered situation.

In magical utterances, there is an appeal to another set of circumstances outside the immediate scene of the agent. This rhetorical scene of magic is characterized by Mircea Eliade as a life lived “on a two-fold plane; it takes its course as human existence and, at the same time, shares in a transhuman life, that of the cosmos of the gods” (1957, 167). Symbolically, this twofold existence is represented by what Eliade terms a homology. Simply defined, a homology is a correspondence between macrocosm and microcosm. It is within this homology that the relationship between mysticism and magic is made apparent. Kenneth Burke quotes James Baldwin in the Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology as defining mysticism as embracing “those forms of speculative religious thought which profess to attain an immediate apprehension of the divine essence or the ultimate goal of existence” (1969a, 287). In other words, mysticism is belief in and the desire to achieve what Eliade called the “transhuman life.” That is, mysticism expresses the human desire to identify with and articulate, through symbolic expression, the innate knowledge of the cosmos.

This rhetorical perspective suggests that a text not only expresses a purposeful and meaningful point of view but also provides the framework by which hearers and readers understand the function of that text. Mysticism as philosophy, from this perspective, reflects a foundationalist perspective. Scott Consigny writes that foundational rhetoric “maintains that there is an order or truth in the world that we may approach or apprehend if we use the appropriate faculty or are inspired and that we may communicate this truth if we speak in the proper manner” (2001, 63–64). Belief in a foundationalist context leads speakers to construct a text according to a mystical understanding in order to reflect that understanding using language. This epistemological stance requires ontological experience and, consequently, knowledge not just of the “proper manner” but an ability to speak in that proper manner. From the audience’s perspective, the apprehension of this truth likewise requires knowledge of the appropriate faculties. Speakers and audiences thus must have knowledge of a shared experience in order for the truth of rhetorical texts to be experienced, understood, and expressed.

The ancient Egyptians articulated this shared, epistemic experience through their highly complex and symbolic onto-cosmological narratives. An onto-cosmological narrative expresses the fundamental beliefs of its cultural background and reveals the ontological concerns of a group situated in a specific time and place. In short, the onto-cosmological narrative seeks to express what is possible and what is ideal and how what the group desires can be accomplished by it within the cultural paradigm (Berlin 1993, 148–49). These narratives create the essential rhetorical situation by explaining both philosophically and semantically “those contexts in which speakers or writers create rhetorical discourse” (Bitzer 1968, 1) in order to be fully involved with the creation and maintenance of a world.

Essentially, these onto-cosmological narratives are foundationalist in that mystical truth is presented as “an independent goal or starting point or origin that is ontologically, logically and temporally prior to human inquiry and knowledge; that is independent of the contingencies of human life, culture and language; and that serves as a criterion for claims to knowledge and meaningful speech” (Consigny 2001, 61). Because of the strong emphasis on all the metaphysical elements, creation stories stress an individual’s participation in the coming into being of knowing. Encoded in the narrative is the nature of truth as both goal and means. Once again, however, there must not be a hard distinction made between the cosmology of the gods and the ontology of human beings. What separates the cosmological truth from the ontological goal of truth is a mere matter of location.

Here we begin touching upon what smarxist and Squizzle were saying, and what the Tobin paper goes into much more deeply: onto-cosmological narratives and reflection of truth. Organizing what is perceived and experienced in the individual and social world in attempts to truthfully reflect and communicate the workings of the greater ontology and cosmology — and vice versa. Understanding the truth of the cosmos and the patterns that it takes over millenia of myth and exigency allows us to view the unfolding patterns of human social and cultural reality, because they are one and the same.

Let’s talk (or let Karshner talk) about language.

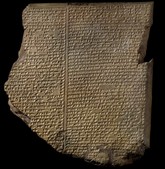

quote: Over Egypt’s long history, many creation stories evolved to explain the onto-cosmological situation of those living on the banks of the Nile. Each creation story addressed the particular exigency of its area and people. What this myriad of stories share is that they are primarily etiological. An extraordinary exception is the “Memphite Theology”, a religious treatise that emphasizes the role of reason and language in constituting reality. In this story, Ptah emerges as the divine reason that creates and maintains the universe. Ptah is characterized as he “who has given [life] to all the gods and their kas through his heart and his tongue” (Lichtheim 1975, 54). The Ennead (the council of gods), according to this text, functions as the limbs informed by the intellect (heart) and performative speech (tongue). Likewise, while Ptah’s intelligent speech is formative, the gods, cattle, and humans (interestingly lumped together) function through their speech and actions as agents of definition. The Memphite text declares “thus all the faculties were made and all qualities determined, they that make all foods and provisions, through this word. … Thus Ptah was satisfied after he had made all things and all divine words” (Lichtheim 1975, 55). Humanity finds itself in a world of linguistic construction. Consequently, to participate fully in this reality, an action is required to determine one’s proper function in context. In other words, one exists only as fully as one’s “command of the word.”

To have command of the word, an individual must know the formative and performative power of speech reflected in the magical vocabulary that emerges from the onto-cosmological narrative. An illustration of the creative power of words is further revealed in the vocabulary of Egyptian magic. For the ancient Egyptians, the primary creative force in the universe was heka, usually translated as “magic”. According to the Coffin Texts (spell 261), heka is the first created force, and consequently, the divine force that “empowered the creation event” (Wilkinson 2003, 110). Heka, then, is not merely “hocus-pocus” but the vitality behind the process of invention and production that establishes the order of existence.

The power of heka was found in its close association with language. In fact, the whole of Egyptian mysticism and magic is encoded in the metaphysics of its linguistics. Therefore, before explicating the word heka, it is necessary first to clarify the complexities of the Egyptian writing system. Despite the philological advances in hieroglyph research, many lay people still believe that the ancient Egyptian writing system was purely pictographic. In reality, this system of writing was far more complex in that the signs used fall into three categories. First, signs could be used to represent consonant sounds. Here, the signs could further represent monoconsonant, biconsonant, or triconsonant sounds. Second, there was a group of ideograms that did function as picture writing. For example, a representation of the heart meant “heart” and carried with it the corresponding sound for “heart” (ib). These signs came with a strike mark underneath to show that they were being used as a word sign and not merely a sound sign. Finally, a type of ideogram called a “determinative” could be used in the writing of a word. This sign came at the end of a word to determine the meaning but did not have a sound value. In this case, the word “day” (hrw) is spelled with the monoconsonant signs for h, r, w and is followed by the determinative of the sun disk (aten) to determine the meaning of the word. This may seem like a complex or even convoluted writing system, but it gave the scribe great leeway in the way ideas were transmitted visually.

The sign for heka is made of three characters. The first is the pictograph of twisted flax. It is a unilateral sign for an emphatic h sound and is there purely for its phonetic value. The second sign is where this etymological dissection becomes really interesting. The Egyptians now insert the word sign for ka. They could have continued to use unilateral signs: a basket for the k sound and the vulture sign for the short a sound. Instead, they use the ideogram for ka which, in simple terms, is the word for the soul; however, the ka is a far more significant ontological concept. The ka represented the “essential self of an individual” (David 2002, 117). Moreover, the ka was the power of creation that allowed an individual to be an active agent in the physical world. Finally, the last sign in heka is the determinative representing a rolled scroll meaning “writing”. Essentially, the sign for heka could be translated as “soul writing”. Robert Ritner describes it better as “at the strike of a word, magic (heka) penetrates the ka or ‘vital essence’ of any element in creation and invests it with power” (1993, 25). In this case, the element is “writing” or the “word”, and heka reflects the creative power of the word. It is important to note that heka refers to the vital power of the word and not the word itself — that is, heka “resides in the word itself” (Ritner 1993, 17). A word possesses its own function and performative soul.

The powerful word that is conjured by the power of heka is hu. Within Egyptian metaphysics, hu is defined as the “authoritative utterance, that speech which is so effective that it creates” (Wilson 1977, 57). What imbues hu with effectiveness is heka, which, preceding it, imparts to hu the very creative vitality that structured the universe. James Henry Breasted links this idea of the creative word to the agency of creation “by which mind became creative force. … The idea thus took on being in the world of objective existence” (1933, 37). Both Wilson and Breasted link this to the concept of logos found in the Gospel of John. Like logos, hu manifests the intangible intent of the creative mind in the tangible world of existence — creative intent yields creative process yields created product. Each of these events is linked by the vital reasoning principle heka.

Hu is most often paired with sia. In a word, sia is perception. Within the context of Egyptian metaphysics, it is further defined as “the cognitive reception of a situation, an object or idea” (Wilson 1977, 56). In the words of the Memphite Theology, sia is that which has been “devised by the heart.” The connection between sia and hu is that hu “repeats what the heart has devised” (Lichtheim 1975, 52). Hu and sia combine to reflect a cognitive process that, through perception and expression, establishes order. John A. Wilson describes this process as “a system which employs invention by the cognition of an idea in the mind and the production through the utterance of creating order by speech” (1977, 56). This cognitive process that moves from perception to speech eventually leads to the knowable order of the universe brought into being through the essential power of heka.

This ability to determine function with speech reflects the power of the divine order. At the root of the power of speech, shared by creator and created, is the ability to reason. Articulated here is the idea of an epistemic rhetoric through which “man could know because he was identified with the substance of God, that is, the universal mind. From the universal mind (logos), man’s mind (logos) can reason (logos) to bring forth speech (logos). This wonderful ambiguity of logos retains the identity, that is, truth” (Scott 1994, 314). Deeper than language is the power of reason that connects humankind to the universal mind. The culmination of intelligent, articulated speech, rooted in perception, was manifested in the ability to form and influence reality. This magio-rhetorical process of reasoning is what links the universal participants together and situates the individual within the onto-cosmological homology.

Okay, but you can’t just willy-nilly say anything and have it fruit magic, right? Right. That’s because magic, heka, is the flip side of the foundational underpinning of the Universe: ma’at. Or, you know, the Source, the Ground-of-Being, All-That-Is, the Divine Spirit… ma’at is the essential nature of reality, and while it is personified at times as a Goddess it is a concept far vaster and more present and more necessary than mere divinity. It is order, justice, truth, balance, harmony, reciprocity, what is Right. If it is the waters that fill the panentheistic aquarium in which we the little fishies all swim, heka is recognizing and making use of currents and waves and whirlpools and eddies that we encounter there within it. But it is ma’at that creates this environment to begin with.

quote:For the ancient Egyptians, the foundational truth that results from this cognitively created system was maat. Maat was the universal idea of order, justice, or truth. More fundamentally, maat was the onto-cosmological principle that connected the divine order of the cosmos with the social order of justice and the ethical reality of human beings. In short, maat, at once, can translate as both an ethical and a metaphysical concept. Henri Frankfort characterizes maat as “a divine order, established at the time of creation,” an order that “is manifest in nature in the normality of phenomena . . . in society as justice and . . . in an individual’s life as truth” (1961, 63). This natural, social, and individual order is manifested in one’s direct use of perception (sia), reason (heka), and articulation (hu). Just as Ptah in the Memphite Theology transformed chaos into order, the king was expected to preserve or reestablish justice within the kingdom, while the everyday Egyptian was to do “what was loved” (ethical) over what was hated (unethical) as had been established since the beginning of time.

For both gods and humans, maat was “the very basis of one’s speech and actions: ‘Do maat . . . speak maat” (Morenz 1992, 117). Another text declares “hu is in thy mouth, sia is in thy heart, and thy tongue is the shrine of Justice [Maat]” (qtd in Wilson 1977, 84). Order is the only true outcome of intelligence. What is perceived and spoken must reflect what is true. Just as word is a manifestation of mind, justice or truth is a product of them both. Their power is found in the articulate expression of concepts. When heart and tongue are in agreement, all faculties are “made and all qualities determined. … Thus justice is done to him who does what is loved, and punishment to him who does what is hated. Thus life is given to the peaceful, death is given to the criminal” (Lichtheim 1975, 54-55). The power of conscious expression is not just revealed in the metaphysical order but in the ethical order as well. The recognition of maat in the expressed order of the universe becomes the sia of the human/social order. The language of human beings must also express this order in a terrestrial sense. This is precisely why Ptah is in “every mouth of all gods and all men.” There is no cognitive difference between the maat of men and gods; the difference is one of location only.

Rosalie Davis nicely summarizes this cognitive, cosmological process: “The two divine principles of perception [sia] and creative speech [hu] are the rational forces by which creation is achieved, when the creator god first perceives the world as a concept and then brings it into being through this first utterance. To achieve this, the creator uses the principle of magic [heka], a force that, according to Egyptian belief, could transform a spoken command into reality” (2002, 86). Egyptian metaphysics was rooted in the idea of developing an awareness of concepts and then correctly expressing those concepts so as to create a “right dealing” and just order. At the most essential level, this cognitive process relied on the correct word and phraseology to reflect the idea that had the power to determine order.

Now, there are an additional ten pages of this paper to go and this is already a behemoth of a post. But since smarxist’s posted thoughts also brought up the Babel myth I will finish up this section, which touches on related ideas, before calling it quits.

quote: While maat was the fundamental principle of order in the Egyptian cosmos, the Egyptian metaphysician recognized that order was not something created and fixed but rather something to be created and that consequently a break in the sameness of order was necessary for true action. Like their Hebrew neighbors, the Egyptians believed that the paradise of maat was threatened by an adversary determined to upset the reasoned, linguistic order that had been established at the beginning of time. Lurking in the netherworld of the Egyptian cosmos was the demon serpent Apophis. According to the mythology, Apophis was the “embodiment of the powers of dissolution, darkness and non-being” (Wilkinson 2003, 221). Essentially, Apophis was the nemesis of the sun god Re. In the “Book of Gates,” Re sails across the sky and through the underworld, governing the world as well as bringing it light and life. Apophis, as the enemy of order, threatens to overturn the divine barque at sunrise and sunset with the intention of preventing the journey that not only symbolizes maat but is the cosmic act of enforcing maat. Aiding Re on this journey is Heka.

In this myth, Heka is linked to Re as his protector. As Robert Ritner notes, “Heka protects the passage of the sun through the netherworld he defends the very created order itself ” (1993, 19). R.T. Rundle Clark underlines the importance of this pairing of Re and Heka, pointing out that “the solar barque is the centre of the regulation of the universe, so it is suitable that it should be manned by the personifications of intellectual qualities” (1959, 249–50). Re represents the agent of maat. As its agent, he must meet the challenges of disorder with the instruments of order. Without the intelligent awareness and proper utilization of Heka, he is helpless in the face of disorder. The agent of order (be it Re, the king, or the average Egyptian) must seamlessly match his or her intentions and actions to the metaphysical demands of cosmic order. The onto-cosmological narrative makes it clear that only intelligent action is true action.

This connection between rhetoric, heka, and Apophis is drawn even more clearly by Ludwig D. Morenz. In his essay “Apophis: On the Origin and Nature of an Egyptian Anti-God,” Morenz moves beyond mythology and netherworlds to explore the etymological meaning of the name Apophis. Morenz identifies two elements in this demon god’s name.The first element ‘3 means “great” and the second element, pp, translates as “roar, babbler, babble.” Morenz believes that pp is “an onomatopoeic word imitating the inarticulate or even nonverbal sound of this mythological water snake” (2004, 203). This construction is similar to the Greek root for barbarian— barbar, which is onomatopoeic for the inarticulate speech of foreigners.

Putting these elements together, Apophis comes to mean “great babbler,” an onto-cosmological concept for gibberish and confused speech. Morenz writes that Apophis is understood to be evil because “language endows meaning and relation, and Apophis is the negation of precisely these ideas” (2004, 204). Yet Apophis was more than a mere symbol of a distant, cosmic crisis. Assman sees Apophis as denoting a “danger that threatens life on all its semantic levels and can attack at any time and in any form” (1995, 54). Because the Egyptian cosmos was based on the intelligent articulation of perception, Apophis threatens it by confusing language and, therefore, wisdom. He is the very antithesis of reasoned speech and order.

In their onto-cosmological writings, the Egyptians clearly illustrate the role of rhetoric as defined by Burke:

quote:Let us observe, all about us, forever goading us, though it be in fragments, the motive that attains its ultimate identification in the thought, not of the universal holocaust, but of the universal order—as with the rhetorical and dialectic symmetry of the Aristotelian metaphysics, whereby all classes of being are hierarchally arranged in a chain or ladder or pyramid of mounting worth, each kind striving towards the perfection of its kind, and so towards the kind next above it, while the striving of the entire series head in God as the beloved cynosure and sinecure, the end of all desire. (1969b, 333, emphasis his)

We all seek order rather than chaos, and then we desire to express that order in some way. Yet it is in chaos, or in the face of disorder, that the power of formative and performative speech is found. The desire to express order is secondary to the need to recognize possibility in the epistemological crisis. Therefore, reasoning- and language-using agents find themselves going from a situation in which “no point of reference is possible and hence no orientation can be established” (Eliade 1957, 21) to one in which they “must consider truth not as something fixed and final but as something to be created moment by moment in the circumstances” that they find themselves in and that they must cope with (Scott 1994, 318). It is within this context of uncertainty that rhetorical magic becomes necessary.

The latter half of the paper is subtitled, “Antifoundationalist Rhetoric and the Demands of Ethical Magic,” so if anybody asks me to share with them what qualifies as demands of ethical magic I will post that half too. But this post is already uhhhhhhhhh of significant length, so despite my interest in demonstrating The Demands of Ethical Magic I must also tend to the demands of ethical posting and abbreviate the journey here to minimize the scrolling necessary for those uninterested in its contents. Also we are probably close to a page break by now and I should get this in at the bottom of an existing page rather than the tippy-top of a new one  I hope that this was enjoyable and informative, typhus et al I hope that this was enjoyable and informative, typhus et al

I don't think I have quite enough room to stitch the second post in here without running afoul of the character limit, so... it is forthcoming.

|

" and then I re-read it last year, with twenty years of trying to develop a modern relationship with this ancient religion and its perception of the world under my belt, and was just like "oh it's about good speech, of course." Having a much deeper understanding both of the Egyptian ontology and a bit more abstractly, the sorts of things they found important enough to write wisdom literature about, made it just make immediate sense to me in exactly the way it did not when I tried reading it without having spent so much time practicing an ability to access the appropriate perspective.

" and then I re-read it last year, with twenty years of trying to develop a modern relationship with this ancient religion and its perception of the world under my belt, and was just like "oh it's about good speech, of course." Having a much deeper understanding both of the Egyptian ontology and a bit more abstractly, the sorts of things they found important enough to write wisdom literature about, made it just make immediate sense to me in exactly the way it did not when I tried reading it without having spent so much time practicing an ability to access the appropriate perspective.

I mentioned this paper in here this summer but never ended up getting into it so... here we are! Please forgive the tone of my commentary having more emphasis on modern metaphysics than ancient history, the topic of this paper blurs those lines quite effectively, don't judge me too hard.

I mentioned this paper in here this summer but never ended up getting into it so... here we are! Please forgive the tone of my commentary having more emphasis on modern metaphysics than ancient history, the topic of this paper blurs those lines quite effectively, don't judge me too hard. anyway there is my gamble of a

anyway there is my gamble of a  rather than being coy and asking first if people here would like to read it, since I have yet to hear "no, absolutely loving not, why would you even ask that, you idiot" in reply when I do ask if I should post things like this

rather than being coy and asking first if people here would like to read it, since I have yet to hear "no, absolutely loving not, why would you even ask that, you idiot" in reply when I do ask if I should post things like this

Yes, it's like a lava lamp.

Yes, it's like a lava lamp.