(Thread IKs:

dead gay comedy forums)

|

I would recommend mapping it out, using long form c, if you're failing to see the contradiction. The contradiction specifically only applies for to "machines" used to produce. And there are defenses of this contradiction. (USER WAS PUT ON PROBATION FOR THIS POST)

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 24, 2024 14:55 |

|

Clearly there aren't any contradictions because if there were you'd elaborate on them

|

|

|

|

This ain't a classroom and you aren't a teacher bub, if you've got something to say or something to ask just say or ask it. Nobody's doing your Econ 201 homework for you

|

|

|

|

BillsPhoenix posted:I would recommend mapping it out, using long form c, if you're failing to see the contradiction. The contradiction specifically only applies for to "machines" used to produce. i'm glad you were probated for this one, because you're obviously being disingenuous. i've explained why there's no contradiction in i think pretty clear terms; if you can't respond, in turn, to my explanation, and instead just pretend that there is a contradiction floating somewhere out in the aether, then you're obviously bullshitting me and just trying (but, crucially, failing) to score points rather than to learn or illuminate anything Ferrinus has issued a correction as of 18:59 on Mar 12, 2024 |

|

|

|

Can we just threadban this tedious motherfucker? His posts are barely English and we're lucky if he ever writes a complete sentence, let alone a complete loving thought.

|

|

|

|

BillsPhoenix posted:I would recommend mapping it out, using long form c, if you're failing to see the contradiction. The contradiction specifically only applies for to "machines" used to produce. converting language into mathematics using set theory to disprove marx by calculating that the sum of his propositions is non-zero ftw

|

|

|

|

to reiteratedisaster pastor posted:was doing believable "am I trolling or am I a poster with imperfectly medicated schizophrenia" posting but the John Nash references really gave the game away, smh yup. if somebody says "I studied econometrics" with someone that sat with John Nash and says that "neoclassical economics are at best loosely related with modern Western economics", they are bullshitting. (still, anyone is free to reply to them if they think they can salvage a worthwhile pretext)

|

|

|

|

I'm Marx

|

|

|

|

|

i've responded to bill like 8 times with answers and questions for him to think about in turn, and he ignored them all — except for the one time he could misrepresent my remark about the problem of induction in an open system (i.e., his "welp, proof is impossible & so is debate, evidence, and reason" reaction). so, it's hard to read him as a good-faith interlocutor, even with the charity dial cranked up to max. so: is wasting more time on him like throwing good money after bad? probably not, if he's mouthing off about a topic some less vocal reader of the thread is also likely to be confused about. remember: public discourse is mostly performance. bill's someone who made up his mind about some things ages ago, and reasons from those incoherent conclusions with great motivation, so we won't convince him that the sky is blue. but we can at least play gallant to his goofus for those following along it's pretty much like the time-honored practice of rubber duck debugging, but for marxist fundamentals — both in terms of the benefits to the explainers and the retention of the ducky Aeolius has issued a correction as of 19:23 on Mar 12, 2024 |

|

|

|

Aeolius posted:i've responded to bill like 8 times with answers and questions for him to think about in turn, and he ignored them all — except for the one time he could misrepresent my remark about the problem of induction in an open system (i.e., his "welp, Yeah it's worth it, you're refining your arguments and playing to the crowd instead. Perfectly valid and a good skill to master.

|

|

|

|

Ferrinus posted:that's why i look it up every time i'm about to use it, to make SURE i haven't managed to misremember it this time around so as to end up losing rather than gaining posting cred also important to do with "limpid"

|

|

|

|

Rodney The Yam II posted:I'm Marx well then maybe you’d like to explain to bp why you’re wrong? hmmmm???

|

|

|

|

Aeolius posted:i've responded to bill like 8 times with answers and questions for him to think about in turn, and he ignored them all — except for the one time he could misrepresent my remark about the problem of induction in an open system (i.e., his "welp, its also pretty funny

|

|

|

|

I think it's crossed the point into being extremely tedious.

|

|

|

Mandel Brotset posted:well then maybe you’d like to explain to bp why you’re wrong? hmmmm??? At this point BP can read my work or Grundrisse my rear end

|

|

|

|

|

So some international current status of Marxism updates because this stuff pops up every now and then https://twitter.com/eliasjabbour/status/1766785632695877716 Elias Jabbour is a bigtime Marxist from around here who received the special book prize award from the PRC for his work "China: Socialism of the 21st Century" (which I still have to read) and was referred by the Brazilian govt to work in Shanghai in some international economic program thingie, so he's legit af. Elias there is giving very high praise to Roland Boer, who is actually a holy loving poo poo professor of the Marxist School of Reimin -- the Chinese consider him the best prepared international Marxist -- and he says that he is on the level of Losurdo and Gabriele. So yeah, it seems that Roland might be the most relevant and actual Anglo theoretician around who can contribute a lot into creating an intellectual bridge for Chinese Marxism

|

|

|

|

mila kunis posted:Machines do not generate surplus value, they add their existing value to the production process. A common counter-argument is that, according to this reasoning, the price of the machine must be equal to the expected value it will add over its useful life (and inversely). Therefore, if a $10 million dollar machine manufactures widgets that are sold for a total of $100 million out of $40M raw materials, the remaining $50M must come from the labor power that went into making the widgets. If only $20M of wages are paid out, there is a $30M surplus that has been taken from the workers. This is fine on the face of it, but it runs into some difficulties. One is that, for industries where a relatively small number of workers is able to satisfy the global demand for a valuable commodity using expensive machinery, you can end up with some pretty big numbers for the surplus labor value that is being expropriated relative to workers in other industries. For example, TSMC operates 4 fabs, and a generous figure for the 10-year TCO for a very modern fab is $30B (some of TSMCs fabs are old, but whatever). So the per-year cost of capital is on the order of ~$12B on the absolute high end (TSMCs reported OpEx is ~6B/yr) Last year, TSMC made $26B USD in net income and has $70,000 employees. So the surplus value per employee is roughly $370,000 USD in addition to what they were already paid. Thus we have a situation where far more surplus value is being taken from workers' labor power in an industry with a staggering fraction of fixed to variable capital, than in many industries with much more variable capital and less fixed capital--the opposite of what is generally predicted by a simple (simplistic?) reading of Marx. The obvious (generally non-Marxist and not necessarily correct) response is that clearly a worker using all that expensive machinery is able to produce more value than a worker without, but this requires that capital creates some amount of surplus value. A somewhat more Marx-compatible response is that these are highly skilled workers who, their work being intrinsically more valuable, create a larger surplus value to be taken while having their wages suppressed below the market level by various means. Another response is that access to the equipment, supply chain, and financing required for semiconductor manufacturing is highly controlled via military and soft power, being selectively granted in some places and denied in others, and this distortion (a type of unequal exchange) allows for more value to be expropriated from a given amount of labor under these particular circumstances than otherwise possible. And of course, Marx himself points out that when a new manufacturing technology is only able to be utilized by some firms (due to patent protection, finite adoption time, export restrictions, whatever), the resulting competitive advantage can cause the ratio of profit to both variable and fixed capital to increase, and this is only reversed once the more efficient technology becomes commonplace. This is one reason why capitalist nations (sometimes) care about the proliferation of advanced manufacturing technologies beyond their realm of control. A common thread in all of these explanations, though, is that it is ultimately the presence of the machine which allows more value to go from the worker to the capitalist. Whether this is because of differential exploitation of skilled labor, the allocation of that capital being mediated by unequal exchange, a short-term competitive advantage mitigating a long term TRPF, whatever...at some point it is arguably more convenient to simply attribute this value creation to the fixed capital itself, rather than trying to precisely disentangle the relationship between workers and the machines they use. If the surplus value was allocated in some societally just and efficient manner, then it would not be any improvement to bean-count exactly how much "value" came from what workers absent the role of fixed capital ceteris paribus and ensure it all goes to them specifically. Indeed a longstanding question in modern Chinese Marxism has been what meaning--if any--the concepts of "surplus-value" or even "capital" have in the context of socialist production. Despite a lot of ink spilled, the consensus is "lol" and the practical focus has been on ensuring that the fruits of workers' labor are used for the benefit of The People and not hoovered by a pack of vampiric morons chasing Number off a cliff-an endeavor which does not seem to depend very much on how exactly you handle the accounting of fixed vs. variable capital.

|

|

|

|

It seems to me these definitions are tedious and esoteric and this guy can't hang on to them long enough to get through to understanding. Which is completely reasonable. eta good shoot tho

Harold Fjord has issued a correction as of 22:03 on Mar 12, 2024 |

|

|

|

Morbus posted:

Ya I think this is crucial. If it wasn't for IP and trade secrets and anyone could just copy ASML's poo poo and hire a bunch of their designers to replicate what they do, they wouldn't be nearly as profitable as they are. IP based rentierism, consolidation and cartelism, are crucial to maintaining profitability - in the presence of true competition, prices would trend downwards towards the cost of production and each individual player would ultimately be ruined.

|

|

|

|

Aeolius posted:i've responded to bill like 8 times with answers and questions for him to think about in turn, and he ignored them all — except for the one time he could misrepresent my remark about the problem of induction in an open system (i.e., his "welp, I think despite being a stupid moron with bad intentions, billsphoenix has been a net boon to this thread. That's dialectics

|

|

|

|

Orange Devil posted:Can we just threadban this tedious motherfucker? His posts are barely English and we're lucky if he ever writes a complete sentence, let alone a complete loving thought. hes actually kind of a good learning tool for idiots like me, but only because of the rest of you. it’s like “what to say to idiots at the bar 101”

|

|

|

|

mila kunis posted:I think despite being a stupid moron with bad intentions, billsphoenix has been a net boon to this thread. That's dialectics

|

|

|

|

mila kunis posted:Ya I think this is crucial. If it wasn't for IP and trade secrets and anyone could just copy ASML's poo poo and hire a bunch of their designers to replicate what they do, they wouldn't be nearly as profitable as they are. IP based rentierism, consolidation and cartelism, are crucial to maintaining profitability - in the presence of true competition, prices would trend downwards towards the cost of production and each individual player would ultimately be ruined. All of this is important, but I think there is a more fundamental issue for industries (or societies) that are in a period of rapid technological change. Suppose you have a situation where more efficient production techniques are developed in about the same amount of time it takes to install the equipment and recoup the costs (or at least much faster than it would take for the capital to fully depreciate in the absence of new techniques). This arguably applies to the semiconductor industry today (certainly it applied in previous decades), but it has applied at one time or another to many industries during the course of industrialization. Under such circumstances, even in a truly competitive market (indeed especially in a competitive market), the production techniques in place across the sector in any given time will not be homogeneous. Some firms will manage to be first to implement newer techniques, and it will take some time for their competitors to catch up. There will also be new (but temporary) demand for the "better" product that has made the older one "obsolete". During this time, the first-movers will enjoy a higher rate of exploitation and higher profits. If this keeps happening, the result will be a higher rate of exploitation coinciding with a higher fraction of fixed capital for years or even decades. This will offset or even reverse the TRPF. Notably, if the addition of fixed capital itself can (temporarily) increase the rate of exploitation, then it is perfectly reasonable, convenient, and even natural to suggest that additional surplus value arises from the fixed capital. Don't get me wrong--you can work within an entirely self-consistent framework where this isn't the case, provided that you have some satisfactory solution to the transformation problem that takes into account the variable presence of different kinds of fixed capital in both the short and long -term...but nobody has really come up with that. In any case it doesn't change the final relationship between fixed capital, labor, and surplus...just the accounting. Conversely, if a higher fraction of fixed capital always reduces profits in the long term, and the near-term is not an important consideration, then the notion of surplus value arising from capital is not very useful. In classical Marxism, the TRPF ultimately prevails over the aforementioned (and other) counter-tendencies, but only in the sense that the equilibrium state of capitalism probably has a falling rate of profit. Does it make sense to focus on the steady-state behavior of a system that has spent the last 100+ years in a violent and unsustainable transient that has encompassed the entire lifetime of every Marxist so far? That's for you to decide. Obviously exponential growth cannot continue forever, and the music must slow and eventually stop. But in the mean time, I don't think it's particularly useful to die on the hill of the TRPF or on the question of surplus value arising purely from labor. Arguably the main utility of Marxist theory in revolutionary socialism is by quantifying to a mostly clueless and mislead public the magnitude of the value they help create, and how much of it goes to people who are clearly doing less than they are. How much of this value comes from this or that isn't really important--if you want to say it comes from the machine, fine, I built the machine, I run the machine, it belongs to me as much as or more than it belongs to whatever fucker "bought" it with stolen money. However you do your accounting, the value created by my boss and/or landlord is gently caress All and Jack poo poo and that is really what matters. Morbus has issued a correction as of 23:50 on Mar 12, 2024 |

|

|

|

mila kunis posted:I think despite being a stupid moron with bad intentions, billsphoenix has been a net boon to this thread. That's dialectics at first I thought he was just struggling to figure poo poo out but he just ignores offered advice and barrels forward without comment and just keeps posting gotchas and challenges bargain basement D&D trolling, but that's dialectics

|

|

|

|

Morbus posted:All of this is important, but I think there is a more fundamental issue for industries (or societies) that are in a period of rapid technological change. Suppose you have a situation where more efficient production techniques are developed in about the same amount of time it takes to install the equipment and recoup the costs (or at least much faster than it would take for the capital to fully depreciate in the absence of new techniques). This arguably applies to the semiconductor industry today (certainly it applied in previous decades), but it has applied at one time or another to many industries during the course of industrialization. quote:

But...isn't that the point of TRPF? TRPF isn't "profit will for sure decline forever" it's a tendency due to causes such as competition forcing prices towards the cost of production. It induces in the capitalist the desire to eliminate competition, form monopolies or cartels, or gain said temporary advantages in the form of innovation. Capital doesn't drive innovation because it loves Hecking Science, it's for the maintenance of profitability to counteract the TRPF. The point of dialectical analysis is that these ideas like TRPF represent motions and dynamics that are counteracted by other forces, not that they are immutable static constants. It is entirely useful for analysis - it's hard to understand what happened in the 70s in the west and the rise of china without it. That the TRPF is counteracted successfully by opposing currents in the capitalist system at different intervals (generally in the imperialist core mind, you could argue plenty of capital has struggled to form or succeed in basic ways in large swathes of the undeveloped world) doesn't mean the notion should be discarded or isn't useful. quote:Notably, if the addition of fixed capital itself can (temporarily) increase the rate of exploitation, then it is perfectly reasonable, convenient, and even natural to suggest that additional surplus value arises from the fixed capital. Don't get me wrong--you can work within an entirely self-consistent framework where this isn't the case, provided that you have some satisfactory solution to the transformation problem that takes into account the variable presence of different kinds of fixed capital in both the short and long -term...but nobody has really come up with that. I'm not well read on the transformation problem, can you explain what this means. quote:Arguably the main utility of Marxist theory in revolutionary socialism is by quantifying to a mostly clueless and mislead public the magnitude of the value they help create, and how much of it goes to people who are clearly doing less than they are. How much of this value comes from this or that isn't really important--if you want to say it comes from the machine, fine, I built the machine, I run the machine, it belongs to me as much as or more than it belongs to whatever fucker "bought" it with stolen money. However you do your accounting, the value created by my boss and/or landlord is gently caress All and Jack poo poo and that is really what matters. A wise man once told me that "it's loving obvious" that the basis of human civilization and wealth is labour and haggling over numbers and value derivations from econ data is pointless unless you want to defend marx's carbuncled butthole at all costs. Unfortunately I want to do this.

|

|

|

|

mila kunis posted:Ya I think this is crucial. If it wasn't for IP and trade secrets and anyone could just copy ASML's poo poo and hire a bunch of their designers to replicate what they do, they wouldn't be nearly as profitable as they are. IP based rentierism, consolidation and cartelism, are crucial to maintaining profitability - in the presence of true competition, prices would trend downwards towards the cost of production and each individual player would ultimately be ruined. I dunno seems like they can manage to go down even with that, it just blocks a simpler way for it to happen. Actually a lot of Marxist thought seems physic-y to me. Like if you had labor replaced with energy/work or something I don't think it'd be that hard to make sense of it. Machines and all are just more efficient than some ways of doing things (but not necessarily, similarly to how only certain structures do something well, and others don't even if they take a lot of energy to form). Like how bikes can let people travel farther. I dunno I think I am pretty naive because everything kinda looks reducible to labor to me. Not like easily but it isn't like a spreadsheet does anything if there isn't labor attached to it (and the spreadsheet even needs someone to update it, to make the program and environment it runs in, the hardware that operates on, the power the hardware needs to run, etc into a big drat web of labor and crystalized labor).

|

|

|

|

mila kunis posted:I'm not well read on the transformation problem, can you explain what this means. The transformation problem refers to the process by which a given amount of embodied labor is "transformed" into market prices. The labor theory of value holds that exchange values are determined by the amount of embodied labor, so there should be some formula or such (at least in principle) to go from there to competitive prices. One issue is that if fixed capital does not generate any surplus value, then industries with a relatively high fraction of fixed capital input and low fraction of labor input should generate less surplus value and vis versa. In this vein, Marx proposed that the rate of profit is directly related to the organic composition of capital (i.e. the amount of human labor involved in production relative to fixed capital). However this is generally not seen, including during Marx's time. Instead, it was often observed that the rate of profit tends to converge (to at least some degree), even across sectors with very different organic compositions of capital. How, then, is it that the large surplus value from labor intensive industries, and the correspondingly large exchange value of the commodities produced, are "transformed" into prices that are reflective of a more uniform rate of profit independent of the organic composition of capital? The answer is gently caress if anybody really knows. Marx (and others) proposed that as investors pile into more profitable sectors (which according to him will initially be the ones with a higher organic composition of capital), competition and overproduction drive some of them out and into less profitable, more capital intensive industries, and that this combined with capital mobility results in a tendency towards an equalized rate of profit. This has never been a fully satisfactory explanation, as there are plenty of examples where industries with smaller organic composition of capital have persistently higher rates of return than other industries. There are examples where this remains true, even as the economy as a whole becomes less competitive and more monopolistic. More broadly, the empirical evidence for a tendency towards an equal rate of profit is itself tenuous, and so this is probably not a good crutch to lean on if you're simply trying to explain why the rate of profit doesn't seem to follow the expected relationship with the organic composition of capital. In my opinion, classical Marxism has a hard time with this problem for several reasons. One is that it is not an adequate framework to fully describe modern financialized capitalism. Another is that it does not adequately address the blunt and very non-market processes that drive exchange between capitalist "1st world" countries and others. Another is that it focuses too much on trying to describe the equilibrium behavior of a decidedly non-equilibrium system--and one that has proven to be largely intractable. My pet reason is is that classical Marxism generally assumes the rate of exploitation is uniform, whereas in reality there is clearly some relationship between the organic composition of capital and the rate of exploitation. But what do I know, I'm just some loving guy. Regardless, if you don't have a good solution to the transformation problem, some "basic" principles of classical Marxism, such as "fixed capital does not contribute to surplus value", become hard to rigorously defend. My personal opinion (and, again, the opinion of many post-Deng Chinese Marxists) is "who gives a poo poo". Imho this obsession with the metaphysical nature of value is a mostly unnecessary and very German philosophical toilet that we really don't need to drown ourselves in. Regardless of exactly how much surplus value is generated under this or that conditions, it is enough to simply observe that, when goods or services are sold and all material costs are subtracted, the money returned to workers is deliberately minimized so that more money can be given to useless assholes who think they know better. Most of the working population isn't even fully there yet, and has been conditioned to accept poor pay, poor conditions, and poor job security because "well the company would go out of business otherwise". I really don't need to get up my own rear end in a top hat explaining how much value came from the oven vs. the baker, I just need people to see how big the pie is and where it is going. To that end, in capitalist countries, workers understanding how to read a 10-K probably has more revolutionary potential than being able to explain the labor theory of value or transformation problem, but that's just like, my opinion man * This is the overriding and most fundamental cause of the TRPF: as fixed capital gradually reduces the amount of human labor required to produce something, the surplus value is reduced resulting in ever smaller returns on ever greater amounts of fixed capital. In the limit of a very expensive machine that produces widgets with minimal labor, there is negligible surplus value and therefore negligible profit to be made from the capital investment. Morbus has issued a correction as of 05:46 on Mar 13, 2024 |

|

|

|

great posting all around everyone

|

|

|

|

i think marx's own explanation for how the rate of profit equalizes across industries in volume 3 is really solid, honestly. i went through the math with some friends and i thought it was a convincing model for how, although more surplus is generated in a high-V, low-C industry, that surplus gets averaged out such that a low-V, high-C industry is de facto rewarded by the market for its technological advancement. the top-level explanation for how this works out is also pretty simple: capitalists, themselves, won't invest in an industry unless they're guaranteed a certain minimum rate of return, and that combined with mostly-technical capitals being able to outcompete mostly-biological capitals means all the capitalists end up equalizing against each other but i'd add three sources of interest here: first, this is a link mila kunis shared with me a while ago: https://kapitalism101.wordpress.com/what-transformation-problem/ it argues that the main mistake most people who assert a transformation problem are making is trying to mathematically model a steady-state system instead of allowing input and output prices to change with each runthrough second, and i also credit mila kunis, is this chinese blog https://taiyangyu.medium.com/addressing-common-criticisms-of-the-labor-theory-of-value-bdf49281fab one of the things it does is survey rates of profit across industries and find that those with a lower V and higher C do tend to be lower, although this is checked by other factors finally, red sails has a really in-depth and math-intensive run at this topic here https://redsails.org/a-category-mistake-in-the-classical-labour-theory-of-value/ in which the author argues that prices factor in social costs to capitalists as well as labor-values, thereby accounting for apparent differences

|

|

|

|

Harold Fjord posted:It seems to me these definitions are tedious and esoteric and this guy can't hang on to them long enough to get through to understanding. Which is completely reasonable. eta good shoot tho skill issue

|

|

|

|

these definitions are simple and so are you

|

|

|

|

BillsPhoenix posted:I would recommend mapping it out, using long form c, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YaG5SAw1n0c

|

|

|

|

Ferrinus posted:i think marx's own explanation for how the rate of profit equalizes across industries in volume 3 is really solid, honestly. i went through the math with some friends and i thought it was a convincing model for how, although more surplus is generated in a high-V, low-C industry, that surplus gets averaged out such that a low-V, high-C industry is de facto rewarded by the market for its technological advancement. the top-level explanation for how this works out is also pretty simple: capitalists, themselves, won't invest in an industry unless they're guaranteed a certain minimum rate of return, and that combined with mostly-technical capitals being able to outcompete mostly-biological capitals means all the capitalists end up equalizing against each other That's fine if the (ostensibly) intrinsically poor rate of profit of high-C/low-V industries merely equalizes with the intrinsically higher rate of profit from high-V/low-C industries. But what if the rate of profit is not equal across sectors, and, if anything, is highest in high-C/low-V sectors? For example, in the US the most profitable sectors are finance bullshit, tobacco, and oil/gas E&P. Out of those, two are high-C/low-V and only one is high-V. But maybe these aren't the best examples. One is made up voodoo, another is an addictive drug, and energy somewhat plausibly has a special relationship to value in modern economies partially independent of labor. Next up is railroads, water utilities, semiconductors and various software bullshit. With the exception of software, all of these are on the high-C end of things (semiconductors notoriously so), and if you look at biggest software firms that represent an increasingly large majority of the industry, those tend to be 1.) capital intensive, owning their own datacenters etc. and 2.) more likely than other firms to capitalize labor. On the opposite end, industries with lower rates of profit include trucking, retail in general, restaurants, and education. I dunno, not looking good imo. You can get somewhat different results looking at gross margin vs operating margin and depending on how you quantify the amount of fixed capital, but the overall trends are similar. Generally speaking, there is a significant spread in the rate of profit across industries, and within that spread, it's hard to argue that high-V sectors come out on top. So why is that?

|

|

|

|

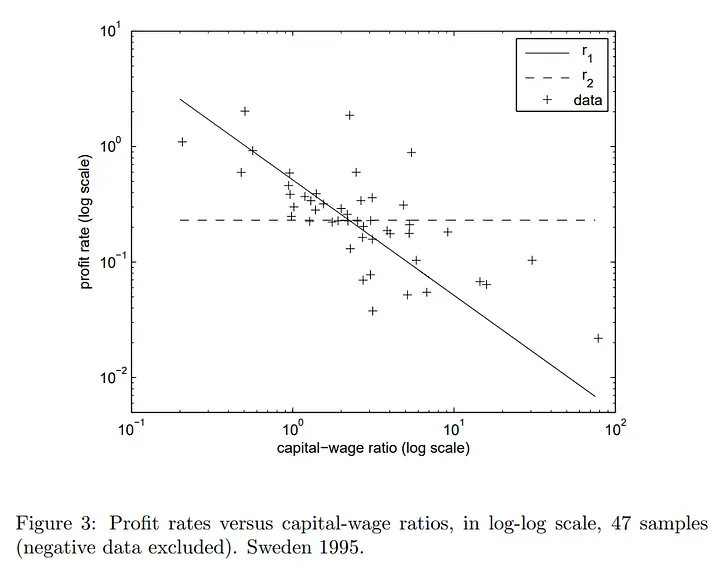

Ferrinus posted:second, and i also credit mila kunis, is this chinese blog https://taiyangyu.medium.com/addressing-common-criticisms-of-the-labor-theory-of-value-bdf49281fab one of the things it does is survey rates of profit across industries and find that those with a lower V and higher C do tend to be lower, although this is checked by other factors i particularly like this article so now that i'm at a keyboard i want to quote the part about the transformation problem. this guy takes an interesting tack: he says that profit just isn't equalized, generally speaking. competition between capitalists does make it trend TOWARDS equalization but the law of value still expresses itself mathematically: The transformation problem is caused by two conflicting assumptions in Marxian economics: LTV and profit equalization. Both are ideas that even Adam Smith argued for. Profit equalization is simply the idea that in a perfectly competitive economy, business would go where the profits are and leave where the profits aren’t, causing profits to equalize across the economy. Marx showed that LTV demonstrates that profitability would inherently be tied to the organic composition of capital, that is, the ratio of investment spent on machines over human labor. This is also sometimes known as capital intensity. The organic composition of capital would tend to equalize within a single industry since everyone would try to adopt the best machines, but it fundamentally cannot equalize across industries. Cellphone manufacturers can’t adopt the same machines that cheese burger producers have. It makes no sense. So one would naturally conclude that they would have different levels of profitability, which contradicts with profit equalization. Marx thought these could be made to agree with a mathematical transformation to convert values into “prices of production” which would make the two assumptions line up. He tried to find this mathematical transformation and never could. It took about a century later for mathematics to advance enough so that various mathematicians were able to prove that such a transformation did not exist. Marx could not have figured this out on his own as it required mathematics that did not exist for another century. (Ferrinus's note: i thought Marx's actual math in vol3 checked out, although it was pretty simple arithmetic and may well have been leaving something important out if this blog author is correct on this point) Both LTV and profit equalization therefore contradict. Does this prove LTV is wrong? No. Just because two things contradiction, does not mean they are not real, as contradictions can actually exist in the economy. There are two possibilities here, either one of the two premises are wrong, or both are correct but operate as opposing “forces” in the economy, so to speak. LTV would “pull” prices to their values, profit equalization would “pull” prices to their prices of production, and empirically, we would thus expect to find results somewhere in between the two. Let’s start with the first case. If LTV is wrong, then empirically, we should measure profits across industries are all roughly the same. If profit equalization is wrong, we should empirically measure that profits differ by their organic compositions of capital (or capital intensity). So which is true? It is LTV. The negative correlation between organic composition of capital and prices has been shown through various studies. quote:“This paper confirms the main results of previous studies concerning labour values and market prices. It is shown that both the labour theory of value and the neo-Ricardian theory yield very good results in explaining data. Differences in estimated outcomes are insignificant. Therefore, approving the approaches developed by Shaikh (1984) and Farjoun and Machover (1983) and having Occam’s razor in mind, we should prefer the labour theory of value for analysing real world phenomena. In addition, a critical point for neo-Ricardian theory emerges: the basis of the transformation debate seems to be fallacious because profit rates and capital intensity are negatively correlated.” Let’s take a look at the second case. It is possible that LTV and profit equalization are both true to a degree, and the actual results lie somewhere in between the two. quote:“The LTV is a ‘deeper’ theory than the TPP, yet its predictions are just as close, if not closer, to the observed reality of capitalism. Through the stochastic melee of the market, the set of prices predicted by the LTV provides one pole of attraction, while the set of prices of production provides another.” This latter paper provides more economic data to confirm that profits do indeed not equalize but as LTV predicts, they diverge based on organic composition of capital. However, they also argue that there does appear to be a somewhat small divergence in prices, not enough to offset the profit trend but enough to be observed. Which provides some evidence for the claim that both laws are operating at the same time. Either way, there seems to be very little evidence to suggest that profit equalization triumphs over LTV. The predictions of LTV seem to hold very strongly. The transformation problem is hardly a “problem” at all, a mathematical transformation between value and prices is not necessary. Both are equal and opposite “forces” in the economy, pulling the prices one way or the other, however, profit equalization provides an incredibly small, hardly measurable pull. LTV without profit equalization is a fairly accurate prediction on its own. The claim that profit equalization is correct but LTV is not does not fit the empirical evidence. In fact, here is a third paper showing the lack of empirical evidence for profit equalization, but even further evidence for LTV.  quote:“The results are broadly consistent; labour values and production prices of industry outputs are highly correlated with its market price. The predictive power is compared to alternative value bases. Furthermore, the empirical support for profit rate equalisation, as assumed by the theory of production prices, is weak.” Again, the empirical evidence is just simply on the side of LTV. Ferrinus has issued a correction as of 06:38 on Mar 13, 2024 |

|

|

|

Morbus posted:That's fine if the (ostensibly) intrinsically poor rate of profit of high-C/low-V industries merely equalizes with the intrinsically higher rate of profit from high-V/low-C industries. But what if the rate of profit is not equal across sectors, and, if anything, is highest in high-C/low-V sectors? i suppose my preliminary reply to this is the post i just made: are you sure that more capital-intensive industries have higher rates of profit the world over, as opposed to just in the US? because it's not like the surplus value captured by the US bourgeoisie is limited to that produced by domestic workers

|

|

|

|

Ferrinus posted:i'm pretty confident fart simpson is wrong here and i'm right, but the distinction is extremely simple: wealth just refers to use-values, but that includes things like fresh air and running water which no one's labor went into creating and which therefore have no value or exchange-value. something has value precisely because, in addition to being useful, someone spent their time and energy finding or making it. but lots of things are useful by default yes i was misremembering this specific line

|

|

|

|

Ferrinus posted:i particularly like this article so now that i'm at a keyboard i want to quote the part about the transformation problem. this guy takes an interesting tack: he says that profit just isn't equalized, generally speaking. competition between capitalists does make it trend TOWARDS equalization but the law of value still expresses itself mathematically: related, both cockshott/cotrell and anwar shaikh have used published input/output tables to analyze with 2 different techniques (regression analysis, and vector distance) to find that the final output value of industries across national economies does closely match with the amount of vertically integrated labor employed in those industries to a very high degree, like >95%. this is not even really marxism, it's essentially just david ricardo's prediction

|

|

|

|

Morbus posted:* This is the overriding and most fundamental cause of the TRPF: as fixed capital gradually reduces the amount of human labor required to produce something, the surplus value is reduced resulting in ever smaller returns on ever greater amounts of fixed capital. In the limit of a very expensive machine that produces widgets with minimal labor, there is negligible surplus value and therefore negligible profit to be made from the capital investment. i dont have any math on it, but im guessing theres something even more fundamental going on here. as your production processes use more and more equipment, then you end up spending a greater and greater total proportion of your available resources on building & maintaining the equipment itself. all real growth (and not only capitalist economic growth) seems to follow some sort of s curve and its not actually exponential.

|

|

|

|

Ferrinus posted:i suppose my preliminary reply to this is the post i just made: are you sure that more capital-intensive industries have higher rates of profit the world over, as opposed to just in the US? because it's not like the surplus value captured by the US bourgeoisie is limited to that produced by domestic workers I'm not sure. But what I am pretty sure of is that to the extent that anyone has tried to find out (including some of the examples you cited), the correlation between the rate of profit and C/V is not great (with a lot or most of the variation among data not being explained by the correlation), and not always in the expected direction For the US, I really like this dashboard: https://dbasu.shinyapps.io/Profitability/ Where the overall conclusion is that, across the entire economy, the rate of profit in the neoliberal period has remained somewhat constant despite an increasing C/V You can argue that, once you account for the surplus value from exogenous labor that is captured by the US bourgeoisie, the actual OCC hasn't increased...but I think that's maybe dubious. It seems hard to argue against the fact that US multinationals, as a whole, have increased the C/V over the last 20 or 30 years. With Japan, too, there is the famous example where throughout the 1970's the Japanese economy seemed to be an exception...until it wasn't. https://www.hetecon.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Morimoto_AHE2013.pdf Some people have tried to study the return on (foreign) capital in China since that became a thing. The obvious conclusion at least during 1990-2005 is almost certainly that the RoP increased as the C/V increased...but 1.) as with Japan that may have been a temporary phenomenon and 2.) as I mentioned before there are debates about how much sense it makes to apply these metrics to a more or less socialist mode of production. If the RoP can vary several fold at a fixed C/V, or if the majority of economic activity takes place within a (still wide but excluding extremes) range of C/V where the correlation to RoP is very poor, or if deviations to the trend can persist for a generation, then what are we supposed to do? It's fine to say that there are some long range macro trends that will manifest in the national (or world) economy, or that there are some broad correlations...but if there are specific counterexamples, does that mean that capitalism is any less bad to me personally? Does it mean we should wait until the RoP gets with the program and matches our expectation to advocate for socialism? It just doesn't seem terribly relevant. I think the main problem I have with this is that, for those who defend capitalism, it's a common point of attack to nitpick these kinds of things. Does it really matter that any rear end in a top hat can point to any of the plots shared in recent points and pick out several data points where C/V is higher and so is the RoP? Do I need to defend rigorously the idea that, if all surplus value derives from labor and this widget was made with less labor it should have a lower price? Or can I simply accept that I have a decent economic theory that makes better predictions than any of the dogshit being taught in Econ 101, and concede that not all labor is equal, not all capital is equal, the rate of exploitation is not always uniform, I can't always predict what the rate of profit is going to do, and that none of this has much to do with whether or not I am being robbed by capitalists?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 24, 2024 14:55 |

|

scary ghost dog posted:its also pretty funny

|

|

|