|

Coming over from Grey Hunter's WITP LP, but largely to offer myself as a source on something completely unrelated. I work in First World War heritage, with a focus on the experiences of the 18,000 British Conscientious Objectors to conscription. Mainly just posting to bookmark the thread, but if there's anything anyone would like to know about Conscientious Objection, the Military system of dealing with it, or the system of Conscription itself in the first world war, please do ask away.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ May 13, 2024 10:51 |

|

mastervj posted:Everything. Ok, well then. Let's go on a rambling adventure in civilian/military history. The organisation I work for is staunchly anti-war, so my usual spiel is a little more judgemental. However, the system is interesting enough and, frankly, bizarre enough, that it's interesting without any value judgements associated with it. I'll just do a bit today, as as much as I'm paid to talk about this, I'm probably not paid to talk about it here. edit: now with answers! Intro The first full, modern conscription in Britain was introduced with the Military Service Act of 1916 - but was a surprise to absolutely noone. Since well before the first world war, even throughout the Boer war, the hard core jingoists and militarists in Britain had been arguing for it's introduction, allowing Britain to project military force relatively equal to (in terms of sheer numbers) the continental conscript armies. Introduction of conscription had been resisted effectively until the dying days of 1915 - largely by the military. Still, given the nature of the mechanised war which was obvious to anyone with a brain by the end of 1914, conscription became a serious option for the first time. Though we're all well aware of the images from the early war of thousands of men in cheering crowds heading off to the recruitment stations, Asquith's government projections estimated that with a fairly constant casualty rate 1914-1915, and quickly dropping recruitment figures, by February 1916 permanent casualties would outstrip voluntary recruitment for the first time - "oh gently caress", in other words. Various voluntary schemes were tried, including the slightly bizarre but undoubtably effective Derby scheme, where men would volunteer their services at a date to be specified "if needed". Of course - they were all needed, eventually. Conscription ended up being a classic "thin end of the wedge" Act of Parliament. Asquith stood to introduce it as a bill on the 5th of January to "make good his word" that all single men would be called up before any married man who had pledged to join under the Derby Scheme was called. All judgements of Conscription aside, this was a convenient bit of political machination, that would win over wavering Liberals. Though the debate over conscription is viewed as one of the most passionate and interesting in British 20th century parliamentary history (and it's all available, for free via Hansard ) it was actually pretty short. Six sitting days encompassed about 100,000 words of discussion. Parliament was divided - the right-wing Tories and more than half of the ostensibly-centrist-for-edwardian-england Liberals on one side, the Labour party and other Liberals on the other. Wavering votes were bought off with concessions to the Bill - some Labour MPs won over with increased power for Trade Unions to have men removed from the system, the ever-rebellious Irish MPs (who never voted on bills anyway) reassured it wouldn't be introduced to Ireland, and many Liberals assuaged by exemption clauses - and the rest were either cowed or caught up in some really excellent and well-made debates for Conscription. In the end the bill passed overwhelmingly, and by the 27th of January, it was law. Every (single) man between 18-41was deemed to have signed up, and was consequently caught in a weird limbo between military and civil law. Mechanisms of Conscription The major block of resistance in parliament and around the country was the burgeoning anti-war movement, now mainly focused on obstructing and interfering with Conscription. The argument was fairly simple, "War Bad", but expressed itself in relation to Conscription in a number of ways. Liberals tended to focus on the rights of the state - the right to conscript, but most importantly, the right to change which laws applied to which men. Religious communities (especially Quakers in Parliament where a significant block of MPs shared the same platform) argued the state could not force a man to go against his beliefs, Trade Unionists saw it as a step towards industrial conscription (and ended up being correct about this), Socialists, Communists, Anarchists all saw it as a capitalist war not worth dying for. The usual anti-war positions, really. Nothing changes. The socialist, trade unionist and religious argument in parliament won concessions in the bill that would allow men to be exempted from conscription. Not to avoid conscription altogether, but to win an exemption after being conscripted. Legally a soldier first, any exemption would have to be proven. Crucial exemptions were won for men in war-critical industries, men with dependents and difficult domestic situations, the medically unfit and (and you'd better believe the house of lords with it's sitting bishops) ministers of religion. The contentious clause came in as exemption "F: On the grounds of a Conscientious Objection to military service". Depending on who you believed, this would either be a group filled with lazy slackers and cowards, or men determined to resist the state pushing them to go against their moral principles. Either way, even the most ardent anti-war, anti-conscription MPs believed there would be a few thousand of them, at most. A conservative estimate (and Asquith's estimate) assumed 4,000 men would apply for CO status around the country - and that most of them would be religious men. The concept was that they could either receive exemption or they would go into non-combatant roles in the army - medical work, sanitary and labour support, or war-critical industry. It was a bit of a bugger, then, when (more than) Two Million applied for exemption, and 20-18,000 of them were Conscientious Objectors. ArchangeI posted:What were the primary reasons given by Conscientious Objectors? Was it all "I can not possibly bring myself to kill a human being" or were there people who knew just how terrible life was in the trenches and decided prison was preferable? Were there any people who objected just because they didn't like the idea of a draft as such? Were provisions made for people who refused to serve under arms, but were willing to sign up as medics? Of 18,000, there were approximately: 8,000 Religious Conscientious Objectors - "thou shalt not kill" being the primary focus of their argument, though variations on this exist for the different religious communities - Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Theosophist, Spiritualist etc 5,000 Political Conscientious Objectors - arguing a variety of points from "the state has no right to introduce this bill" to "i'd prefer to fight against capitalist bastards such as yourself, your honour" 2-3,000 "Ethnic" COs - usually German or other triple alliance countries, or Russian. Didn't want to fight against family, or felt unable to. In the Russian case, most of them were Jewish refugees, and fleeing a pogrom to have yourself conscripted to fight "for" the Tsar as one of his allies wasn't something they could do. The rest, sadly, are unknown - but those are the big three. "Not liking the draft as such" was a common argument - either that the conscription bill didn't work, or that it violated (as it did) the non-coersive nature of the British state apparatus. edit: It's worth noting that the argument was both "I cannot" and "I will not" - Morally incapable of committing an action that resulted in death, and Morally capable of resisting any pressure to do so. Medical services - tricky one! The common conception is that COs became stretcher bearers and were heroes, or were total coward bastards who sat in prison getting fat. Medical services provided a minority of COs with an "Alternative" military service. COs joined: The Friends Ambulance Unit - Quaker-specific (but took non-quakers), medical unit providing services behind the lines at home and abroad. Interestingly, not usually allowed to serve with British soldiers in case they infected them with anti-war thoughts, but served with French troops instead, the "Section Sanitaire Anglaise". Maximum strength at any one time of 2-3 thousand (estimated). Around 4,000 COs served with them during the war. The Royal Army Medical Corps - Many COs expressed a willingness to serve with the RAMC, but the relatively strict selection rules saw most of them turned away. The RAMC simply did not want to be swamped by COs, so, in the end, relatively few worked with them - only 1,000 or so. Many men in both of these groups joined up prior to 1916, as it was a voluntary activity where they could be guaranteed a "non-combatant promise". In the case of the RAMC, in the great manpower crisis of 1918, these promises would be revoked - sending RAMC men into prison for not fighting. feedmegin posted:Historically, religion. Quakers take 'thou shalt not kill' seriously, for example. And yes, there was a non-combatant corps in the British army in both world wars, though members would get a lot of poo poo from the other guys in the army (mostly doing manual labour not medical stuff though; the army only needs so many medics). Quaker stretcher bearers are "THE CO", the example that gets brought out because it's interesting, easy to understand and possibly the least controversial. A well-behaved and productive member of society refusing to kill (how deviant!), but agreeing to save lives is a more palatable story than the East London Russian-Jewish Anarchist telling a drill sergeant he'd "take his baton and The non-combatant corps is both incredibly interesting and not very well known - but it's intersection with the "Absolutist" objectors, the men who really did stick it out and refuse to serve, facing torture, prison and death, is known very well. lenoon fucked around with this message at 14:11 on Jan 15, 2016 |

|

|

|

Cyrano4747 posted:There is a LOT invested by people in the Battle of Britain being the thing that saved the world from Hitler. I don't think even invested so much as has become part of the national spirit of Britain. It's our finest hour, our shining moment, and it's at this point more national myth than historical fact. It's when the few, the good middle class white boys of the empire, aided by their working class mechanics, stood up to be counted when jolly old tory St Churchill called, and knocked dastardly Jerry for six while copping off with the WAAFs and never, ever, ever stopping, or dying, or failing. It's the dog at the end of the runway, it's the hurried pint and a cigarette while you dash out of the mess to your waiting Spitfire. It's the university Boffins (before Universities became breeding grounds of dastardly left-wing academics!) turning their brains, universally, towards Radar, and the young women marrying pilots as the dogfight contrails soared overhead. It happened in the summer, and it never rained. It's glorious, it's immutable, it's the Golden Age of capital-B Britishness. The national myth doesn't include the Polish, or the Empire, or the French. It barely has Hurricanes (and it certainly doesn't have any of the turret fighters), it has no worry or failure, or death. The Luftwaffe are either comically evil or faceless villains. It's the most mythologised bit of history I've ever come across, and it's totally and utterly fascinating as a result.

|

|

|

|

bewbies posted:I wrote one of my theses on the Battle and I don't think any of the works I used (or have read since) was anything like this. I suppose I don't consume much popular history (let alone British popular history) but this really isn't how it is portrayed academically by any source I'm aware of. Yeah, this is not the academic understanding of the Battle of Britain - it's a pretty crude caricature of the British public's understanding. And our politician's understanding of it as well.

|

|

|

|

I'm intrigued as to the "other country" option there. In terms of Soviet myths, I think my communist great-uncle propagated the most common one - the single handed victory of the proletariat against the bourgeois fascist, the wholly-united-no-dissent-or-problems Great Patriotic War. No wonder I'm more interested in public perception of history than history itself these days.

|

|

|

|

SeanBeansShako posted:For some reason, Land Of Hope And Glory started playing in my head when reading this so welp I guess we Brits are all indoctrinated. Also, considering the film has the decency to mention the Poles (though annoyingly portraying them as unprofessional) is more accurate than the National myth? Thanks, I call it my Dan Snow impression.

|

|

|

|

It's the gayest book and also the most wonderful. I don't think it's very boys own, as I read a fuckton of boys own style travel writing from 1850-1920. Lawrence had a romanticised but also really cynical way of looking at his situation - romanticised towards the Arabs and cynical towards the British. It's pretty delightful to read, but also romantic, depressed and sadomasochistic. It's very much in the tradition of British imperialist adventures - a romantic and ever-so-slightly failed poet encounters the other and falls in love with it, seeing "home" as a decadent society fallen from the "pure grace" of the foreign.

|

|

|

|

Certain parts of the middle class in Britain in the late 19th and early 20th century were essentially born into a comfortable servitude as part of the empire's civil service, which is an interesting topic I can go on about at length, but yes: our current government is desperately trying to drive us back to the golden age of 1913 at all costs.

|

|

|

|

JcDent posted:Thanks for the ACW and Franco-Prussian explanations (those two were so similar I thought I was rerearding the post). Hey! I know a solution to this problem! Conscription and Tribunals Welcome back! It's March 1916 and the Military Service Bill has now become the Military Service Act. An estimated couple of hundred thousand men are about to - for one reason or another - apply for exemption from the British Army. The rest of the British population, aged 181-41, male and unmarried, is about to learn what "attrition" really means. The Exemption process was poorly thought through, and implemented in the grand style of late 19th century English bureaucracy, by worthies of the parish whenever they could be bothered to do so. Exemption from the army had to be won - men were "soldiers until proven otherwise", which was done through applying to a local Tribunal. This most civic of boards was convened at a parish level2 and had the difficult and exacting task of deciding which exemptions were to be passed, and which men were to be sent to the army. They received little guidance initially, and usually had voted themselves into existence from pre-existing volunteer enlistment boards. Their job was "simple": Bearing in mind the needs of the Army and the Civilian economy, and the law, assess each individual application for exemption through a separate hearing3, and decide whether or not a man would go to the army. They could pass few verdicts: Total Exemption, Temporary Exemption, Refused Exemption and Exemption from Combatant Service Only - this last one would cause problems. I'm often harsh on the Tribunals, and now, having read through more extant Tribunal records than probably anyone else, I think I can rightfully say that they did a hard job badly, with no intention of doing it well. Staffing the Tribunals with those patriotic enough to have been on enlistment committees was a poor choice. Allowing the Army a Military Representative on each Tribunal to "look after the needs of the Service" was counter productive. Allowing Tribunals to operate with no oversight beyond Government Circulars4 looks, now, like hilarious negligence. In short (and short it must be because otherwise this is long) Tribunals sent as many men as they could to the Army. In rural and urban areas alike, this caused vast and long-term hardship for both the dependents of conscripts and their local economies. Rural Tribunals were usually more lenient, understanding the needs of industries around them, and often operating in a small enough area to be able to see the economic cost of drafting vital individuals. Urban Tribunals were rather different, and the separation in class, education and occupation between the grandees of the Tribunal and the men they encountered made for more volatile and difficult sessions. Compounding this was the simply enormous volume of work Tribunals had to do. With each application comprising several handwritten forms, to be read by each member of the Tribunal, to be summed up verbally at each hearing and then a list of questions to be read and answered, the Tribunal system was well set up to process several applications an evening. The problem can be described quite simply by comparing two Tribunal minute books I've worked with, on the same day. Monday, 5th June 1916 (I remember this one because it's when Kitchener died). Yiewsley Tribunal - 5 applications Battersea Tribunal - 71 applications scheduled For an (ideally) 3-5 hour Tribunal session, that is an impossibly large amount of work. Yet each application was supposed to be judged on it's own merits, fairly assessed, and decided upon. Even without including the Conscientious Objectors who made the Tribunal system famous for it's inadequacy and bias, there's accounts of fights breaking out, Tribunal members violently disagreeing, Trade Union leaders having the Military Representative followed home and assaulted5 for threatening conscription against a proposed strike, etc etc Enter 18-20,000 Conscientious Objectors. Men whose principles were setting them against the entire system of military conscription. Not universally hyper-intelligent, or good at debating, or anything like that, of various backgrounds and motivations and abilities, with very different relationships to Tribunals, different domestic situations and occupations. They are, however, united by two things - a stubborn refusal to be conscripted and a willingness to never, ever, shut the gently caress up in a Tribunal hearing. Setting Conscientious Objectors, protected by a vague and poorly-written clause in the Military Service Act: "Exemption may be granted on the basis of..... A Conscientious Objection to Military Service (note that this Exemption may be from Combatant Service Only)" against a highly pressured, creaking, biased and above all hyper-patriotic Tribunal board led to the expected outcome. Aside from the barrage of insults, slurs, direct attempts to provoke men into a violent defensive reaction6, the constant variations on the theme of "If it were up to me you'd be shot", the numbers tell the story well. Between 18 and 20,0007 applications for exemption as a Conscientious Objector Between 18 and 20,000 exemptions legally due under the law provided they could be evidenced 87 known8 exemptions Now, I've been accused of bias against Tribunal members because I work with the group that they treated poorly (and often illegally), but there's something very clearly up with these figures. Even slashing that 18-20 thousand exemptions "legally due" to a much, much smaller number - say 10 in every 100 COs could legally prove a "Conscientious Objection to Military Service", and far more than this could, we'd still be looking at a couple of thousand COs legally completely exempt. If we were generous to say, the Quakers, and saw them as a group who had an apriori legal claim to CO status, we'd have 5-6,000 exempt men. So whatever my bias against Tribunals - and if you're reading this [Redacted], we will resume this conversation in April - this is not a system that functioned as it was intended to. The vast majority of COs received either No Exemption, or "Exemption from Combatant Service Only". This provided them with the first of many choices which would shape the next five years (and far beyond) for them. Do you accept "Non-Combatant Service" and go into the army in a Non-Combatant role, or do you refuse it? Either way, a week or two after your Tribunal hearing9, you would receive a polite call from a Policeman asking if you intended to report to Barracks. After that - arrest, a short Magistrates Court Trial as an absentee, and then - handed over to the military. --- I actually have to get back to work on doing this, but I'll do more later. I was actually on TV talking about this recently, for a very brief look at a terrified me, you can check out Antiques Road Trip (series 5 episode 14) on bbc iplayer. 1. 18 year olds could be conscripted, but not sent abroad - or initially to the army at all, until they were 19. An exception was made for Conscientious Objectors: "You're too young to have a Conscience! You should be locked up!" 2. Usually on a parish level, but in places where this was difficult/impossible - such as large cities - they were convened on a (urban) borough level 3. Industries and employers could apply on behalf of their workers, so batch applications and hearings were not uncommon 4. The Tribunal minutes for Wandsworth show that Government circulars were voted to "lie unread" until they piled up to a literally dangerous degree in 1918, two years after they were first received. 5. St Pancras Tribunal, late 1917 6. My favourite is the question "If your wife was being assaulted by a German, what would you do? Allow him to carry on his beastly violation?" and the possibly apocryphal answer "I may hit him. But I wouldn't declare war on his country", or, elsewhere in the world (well, Tower Hamlets) "Ask me that outside". Of course, COs waving copies of the Communist Manifesto or singing the Red Flag, bringing a Bible to the hearing and pontificating from it, or being backed up by a Choir (either socialist or religious) probably gave as good as they got. 7. Tribunal records were largely destroyed after the war. This number has been stitched together from a number of sources, most prominently the Cyril Pearce CO Register. The 20,000 is my own estimated figure going from my own work on inner London. Extrapolating from known numbers in Middlesex to cover the other parts of the city with a similar population density, we go from ~2k to 3 in London alone. 8. Fully exempt men are difficult to find. Once exempt they disappear - other COs are tracked by army and prison records. 9. Possibly, anyway. If you disagreed with your Tribunal hearing, you could Appeal to the County Tribunal - records of the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal can be searched, for free, here - try looking up Charles Titford and the Walker Brothers, and then, if they still didn't give you the verdict you wanted, the Central Tribunals meeting in London, Glasgow and Cardiff beckoned, if you were allowed to apply there by the Appeal Tribunal.

|

|

|

|

ArchangeI posted:Really makes me appreciate the procedure I had to follow when I was drafted. With more than 100 Imprisoned Conscientious Objectors going into the Houses of Parliament between 1919 and 1939, the second world war and national service systems were significantly better - Objectors were shuffled into their own Tribunals that were set up specifically to deal with them. Not that they got off light, but it was acknowledged that the people in charge of determining exemptions based on industrial need were not always the best people to judge conscience. Can I ask where you were drafted? And what happened?

|

|

|

|

Trin Tragula posted:

Even then, the wholesale stripping of protected industries until the government hastily issued guidelines amounting to "No, you cannot keep conscripting men in completely exempt professions", after the slow decline of the mining industry was traced to a) huge amounts of men leaving voluntarily and b)everyone else being conscripted, ended up leading to virtually complete nationalisation by 1918.

|

|

|

|

Yeah that's bullshit. The effort the army went into giving it's men "why we fight" lectures throughout paid out in making the British army mid45-46 as politicised as it had been since.... christ... the Levellers?

|

|

|

|

SeanBeansShako posted:Hell, there was quite a large Pacifism movement that sprung up and hung around for most of the fifties as well wasn't there? Yeah, largely sustained by soldiers returning home. I think the pro-Attlee movement is probably a little overstated, largely because historians don't tend to like acknowledging the anti-Winston "Labour will bring in 'some form of Gestapo, no doubt very humanely directed in the first instance.'" Churchill movement. It's an interesting pile-up of coincidences: Churchill's coalition government acting to keep Labour in line, giving concessions to social projects and re-legitimising Labour as a governing body The Beveridge Report aimed at ostensibly "improving the coordination of the war effort" but actually aimed at proving the legitimate need for social(ist) reform was well read and posited as a "why we fight". So Churchill's election platform of "gently caress social reform, let's go back to the glory days of the 20s" was unpopular, especially as in 1943 he'd asked the country to rally round the war again so that they could build a better, socialist-style world. Attlee, Bevan, Bevin and even Morrison (a First world war Conscientious Objector, in addition to being widely decried as a terrible human being) being popular and effective and managing to appeal to a much wider section of society than, say, MacDonald's government. The desire for everyone to build a better country after the war that didn't repeat the disasters of the post-ww1 liberal and tory fuckups, which were painfully well remembered. The democratising effect of national service actually occurred (as much as this goes against my "conscription is universally lovely" platform) in the Second war compared to the First, which definitely had the effect of politically educating a section of the population that would have had no particular interest in politics and also exposed apolitical soldiers to crazy incredibly politically motivated soldiers.

|

|

|

|

I left off at possibly the most boring point last time, so let's do What Actually Happened to Conscientious Objectors, a CYOA story Certificate of exemption for Combatant Service Only So, you've left your Tribunal and they've granted you "Exemption from Combatant Service Only" (ECS). After a final rousing chorus of the Red Flag/Simply Trusting God Every Day (delete as appropriate), you have a couple of choices available to you: 1. Accept ECS, and join the Non-Combatant Corps at your assigned barracks (turn to A) 2. Reject ECS, and refuse to turn up to barracks as ordered (turn to B) 3. Reject ECS, and go on the run (turn to C) A. Congratulations, Private! You've just joined the Non-Combatant Corps. Here you will be expected to follow military orders, wear uniform and be called "Private X" until you are demobilised. After drill and an above-standard level of physical and verbal abuse, you will be formed into a unit with a variable amount of other Conscientious Objectors and sent to provide logistic and labour support to the military at Home or behind the lines at the front. However, you will also be given a written guarantee that you will not be expected to handle a weapon at any point in your time with the NCC. What constitutes a "weapon" is up to your commanding officer, and what you will work on is up to your own individual conscience - some COs found loading ammunition morally acceptable, while others objected to handling even the constituent parts of military material, agreeing to handle only foodstuffs, uniforms and medical supplies. If at this point you've changed your mind; turn to B. The Non-Combatant Corps is possibly the least-researched aspect of the Conscientious Objector story. Regionally organised Battalions were allocated to tasks varying between road-making and camp setup in Wiltshire, to loading material for the front in the coastal ports, to sanitary and labour support in France and Belgium. All NCC Conscientious Objectors were Privates, and were led by NCOs and Officers from the regular army. In at least some cases it was used as a after-injury convalescent posting, either prior to discharge or rotation back into the front. This, as you'd expect, created a great degree of friction between the ranks of the NCC. Many NCC men found the work to be morally acceptable to their objection, though semi-frequent strikes from 1916 to demob attest to localised incidents of dissent, usually around what exactly constituted directly military work. During the "backs to the wall" crisis of 1918, attempts were made to force NCC men into combat positions, causing a wave of strikes at exactly the wrong time, and additionally probably leaving several NCC men in areas occupied in Operation Michael (I know they were in Rosieres on the 25th of March, but I can't find anything else about them). The NCC get the short straw of both military and pacifist studies of the war. To military historians they're a difficult and irritating type of labour battalion, and to pacifists they're the "guys that joined the army". I like them though, I think it's drat difficult to define the exact limits of your personal morality - must have been a hell of a precarious balance. B. So, you've decided to reject the Army. You go home and wait for your call-up date to pass. Some time after, you are arrested (sometimes politely), and brought in front of a Magistrates court, which will usually fine you 40 shillings (apparently over £400 in modern money - which seems rather high), which you will not have to pay, because it isn't bail. You're going to the army anyway. From the magistrates court, you're escorted under guard to the barracks you should have reported to and issued with a series of simple orders: Put on a Uniform. Stand to attention. Sign your enlistment forms. Rejecting all of these necessarily puts you in a lot of trouble. Depending on when and where you're resisting, you might then face a few different experiences: March 1916: The military, not knowing what the hell to do with you, will send you to court martial and give you 28 days confined to barracks guard house. May 1916: You're quite likely to face physical abuse of varying severity, from a beating, starvation and forced physical exertion until you pass out (The Walker brothers, from North London, all went through this at Mill Road Barracks), to "being found with your throat cut in barracks surrounded by NCOs whistling innocently" (a "P.D Smith, from Bolton", though we know bugger all else about him). From June 1916 onwards: Less likely (but still possible) that you're going to be beaten, but more met with an exasperated sigh and a court martial. The court martial will aim to get rid of you - 1-2 years for disobeying orders, and a transfer to a civilian prison. If you've been released from a prison sentence back into the army, congratulations, you get to do this all over again, and again, and again, until the war ends. Unless you're one of "the Frenchmen", your involvement with the military temporarily ends here, and you're in the loving embrace of the British prison system.  London COs "out of prison", but in Dartmoor Prison - November 1917 C. Doing a runner. Are you: a talented artist, poet or writer? If so, you might be in luck, having sufficiently powerful and influential friends might well mean you can spend the whole war "working" on fruit farms without ever being checked up on by the Pelham Committee for the Employment of Conscientious Objectors. While registered with the system, you've managed to completely escape it. Lady Ottoline Morrell and her less-famous MP husband, Philip, somehow managed to shelter about half of the Bloomsbury group on their estate, largely while loving them/letting them gently caress each other. The literal definition of the intellectual CO who skipped the hardship and went straight to the fun bit of being a sexually liberated hedonist. If you aren't lucky enough to be a middle-class author, going on the run is difficult, but possible. Networks of sympathisers exist around the country which will hide you, or attempt to get you to a largely sympathetic port - Liverpool or the Clydeside - who will get you to the USA, or to Ireland. COs on the run are periodically picked up throughout the war, and it's unknown how many evaded conscription completely. A fair few were sheltered by the North London Herald League, a very active, very organised group of Socialist agitators operating in North London (surprise surprise), who put them to work writing agitprop and as trade union liaisons. Others managed to spend the entire war in the central offices of the No-Conscription Fellowship, churning out articles and propaganda, and somehow being missed by frequent raids on the property. Similar groups existed around the country, and the number of COs sheltered by these groups is unknown. My favourite story of COs doing a runner is a small group who just went on holiday to Dartmoor for six months, only being picked up when COs started to be sent to the prison there because they overheard the imprisoned COs talking and went over for a chat.  CO produced Christmas Card, 1917 Next up: Prison, Work Camps and Newspapers

|

|

|

|

Koesj posted:Hey lenoon that's super interesting, and to me it seems quite progressive (or practical at least) that option A was even possible. It really was! As much as I give the military system a lot of poo poo (mainly due to what happened to anyone who took up B), the formation of the NCC was a good move. It freed up men for the front, and allowed somewhere between 4,000 and 6,000 men to serve with the army without going against their conscientious principles. It's formation was largely due to progressive and liberal forces in parliament (mainly capital-L Liberals, Quakers and some of the anti-conscription Labour men) calling for some kind of officially sanctioned status for Conscientious Objectors. They couldn't get absolute exemption for them all (though they continued to try unabated), but it was a major compromise from the most likely alternative official position of "gently caress 'em". It's probably more practical and pragmatic than progressive - the NCC men received a lot of poo poo from the army, from parliament, and from the general public who all periodically complained about even the mere existence of the concession - but it was a good step on the road to the far more progressive system set up in the Second World War along similar lines.

|

|

|

|

Empress Theonora posted:Chalk me up as another poster intrigued by the whole Non-Combatant Corps concept. I'm sure Byzantium in HoI would have space for a Conscientious Objector movement...... I like the NCC, and work is done, so I've got time to say a bit more about it. The important thing to remember is that they were, really, Soldiers. Non-Combatant soldiers, certainly, but still men who had agreed to sign up to the Army. Their non-combatant status was guaranteed only by a promise, and when it came to promises, the British Conscientious Objector of any stripe had heard many and seen them all broken. So, in a lot of ways, it was up to each individual man to define what he felt "Non-Combatant" meant, which, in practice, meant organised consensus within units leading to strikes, slowdowns and refusals to work. Their status as men apart from the army led to friction, but it also led to systematised discrimination. They were paid less, and denied the post-war salary increases. The last (that I know of off the top of my head) were demobilised in April 1920, and Winston Churchill repeatedly insisted in Parliament that they were "Soldiers first", so he could do with them as he pleased, but ignored the contradiction in treating them as COs first (poor pay, slow demob) and soldiers second. They were hated by popular opinion, and by the Army:  Propaganda postcard, probably 1917 but they were also disliked by the harder fringe of absolute pacifists because they looked like this:  NCC men doing washing, date unknown. Trapped in a limbo of not-a-soldier and not-a-"proper"-pacifist, they were largely ignored by the wider movement, and in many ways remain ignored today. My own organisation doesn't like to focus on them, something I've been (pacifistly) forcing through, that their stories were important, and in terms of understanding the individual morality of Conscientious Objectors, probably more important than looking at the better-known Absolutists who could make no compromise. They negotiated a minefield of moral, legal and military ambiguity, doing what was right for them, and succeeding in renegotiating the terms of their own non-combatant status on several occasions. They were massively influenced by the actions of other CO groups and protested on their behalf - something that the Absolutists wouldn't deign to reciprocate until late 1919. This negotiation often took the form of strikes, as described by Catherine Marshall in "The Tribunal", the newspaper of the No-Conscription Fellowship, printed 7th December 1916:   Apologies for the terrible artifacting. Marshall, you'll note, is far more concerned with Clifford Allen (chairman of the NCC, and her lover/partner) and the other "Absolutist" COs, going so far as to ascribe the strike to his presence at Newhaven. This is probably total bullshit. While Clifford was a charismatic presence, this description is far more a propaganda move on Marshall's part, positioning the Absolutists as the "true believers" in the movement, at a time when what it meant to be a CO was under rapid debate. On an individual level their stories are very poorly known, and the official records of the NCC, such as they are, are poor. Stitching together individual COs WO363 files (British army service records), you can see a precarious balance that is both self enforced and enforced by military justice. COs withhold their work as NCC men, leading to individual and collective punishment - but sometimes with the punishment of the Officers creating the problem. Others are disciplined for preaching religious or political "sedition" to the rank and file combatant soldiers, and this never stops throughout the war. The option to "Change your mind" was there as well - several thousand COs (between 3-4,000 officially spent the war with the NCC, perhaps 12,000 were sent to it at some point, with 7,000 of those going straight from there to prison) spent some weeks and months with the NCC before deciding that they could not, in actual fact, cope with the compromise demanded of them, and deliberately broke orders to an extent that prison was the only option. I find these men fascinating, showing that objection was not always an automatic reaction, but something that not only varied, but varied over months of internal and external debate before they took their choice. Life with the NCC was not easy, but COs making the choice to abandon it would surely have known about the brutal conditions of the prisons, especially once COs began to be released from their first sentences in September 1916. One of the best books on Conscientious Objection and the NCC isn't a history but an autobiography, George Baker's "Soul of a Skunk". Baker was a socialist CO, and wrote pretty much immediately after the war in an accessible and pretty drat funny style, so that he could explain to his son what he had done during the war. He was one of the men who took up NCC work initially (after what he describes as an "adolescent-romantic attempt at ending my own life", he's such a self disparaging guy, because it is good evidence of the sheer trauma breaking the status quo was for some men), but after around six months rejected it, choosing an indeterminate time in prison, one that drove him nearly to insanity. He found the NCC difficult to adjust to - wearing uniform and despising his "cowardice for not choosing prison", finding the religious men ("those inflicted with humpty-dumptyianism") who were happy with the NCC tiresome and more irritating than the Officers who shower them with insults. His realisation comes from working with a POW and a "Rabelaisian Dockworker", who finally makes up his mind for him; "George lad, if you 'ate the f_______n khaki, why'd you f______n wear it then?". With that, he talks to another CO in a similar situation, and challenges a friendly NCO to give them any order - he's told to pick up some scrap paper and put it in a bin. He refuses, and he's off to prison until 1919. Fake edit: If anyone can find an electronic copy of Soul of a Skunk, i'd love to see it. Real edit: Hogge Wild posted:When you get there, could tell also about the system they had in WWII? Yes, of course! I don't know it as well, though. lenoon fucked around with this message at 19:33 on Jan 25, 2016 |

|

|

|

Imperial India was certainly run poorly, but I wouldn't say significantly more or less corruptly than mainland Britain*, until the early 20th century - and in some cases beyond. Turns out a mix of corrupt capitalist investors and landed gentry are a bunch of dicks wherever they rule, who knew? *aside from engineered famine, which happened in Ireland, which I guess is not technically mainland Britain

|

|

|

|

feedmegin posted:That's not quite the same as 'engineered', which implies some moustache-twirling guy in the British government sat down and explicitly thought to himself 'how can I starve as many Irish people to death as possible'. Same difference as between the British concentration camps in the Boer War and the Final Solution. Engineered doesn't necessarily have to mean "created to cause suffering", it could be that it was a situation set up deliberately that could only ever end in one way - an unintentional (but not unforeseeable) catastrophe. In terms of deliberate systems in place, the tax-farming-style landlord system and discrimination against catholics set up a populace dependent on a single cash crop (actually beef, not potatoes) for export, at the whim of an essentially feudal overlord collecting money as he saw fit to parcel off to the landed gentry usually living somewhere in England. This system relied on massive levels of subdivision and enclosure, which the British government knew about and wrung their hands in mock-condemnation while agreeing that it was all very terrible, but gosh didn't the landlords bring in such huge amounts of money for the landlords. Ireland ended up with a Cotter-farmer population who could only survive on a crop that needed little land, little investment and could feasibly feed a family throughout the year - the potato. So, we have a system whereby:

This system is theoretically sustainable as long as a) Nobody cares about the lives of Irish farmers and b) You really think monoculture is great. Luckily for the British Government, and unluckily for Ireland, both of these conditions were in place in the 1840's. The (first) Devon Commission (I want to say 1844 here, but it has been a while since I looked into this, the date could be wrong) clearly points out that the Irish cotters are worse-off than virtually anyone else in the Empire, and that monoculture is a terrible idea. It also points out that the Landlord-rent collector-Cotter relationship is unsustainable. Even before the Devon Commission sits, the House of Commons is being endlessly needled about how damaging the Irish Poor Law and the Corn Laws are in this situation, making a populace that is on the edge of total economic collapse, but the main worry being: Corn Law Bill of 1841 posted:a "very considerable decrease" of the present protection would discourage British agriculture, might render this country dependent upon foreigners for a supply of the first necessary of life, and might, in the event, of unfavourable seasons, expose it to the horrors of famine. So, in 1841, years before the blight, the government knows that the situation is set up for a fall. It has been engineered to do so by the Landlords sitting in the Commons and Lords. Not engineered to fail, but engineered to produce the maximum amount of capital possible. The response from the Commons is to strike down Ireland-specific amendments to the Corn Laws and the Poor Laws in case the delicate balance of "not having to spend any money on the bloody irish while still wringing the country dry" is upset. By the time 1845 rolls around and brings the blight with it, we have (some) Irish MPs and (some) Whig MPs screaming in the Commons that Irish Cotters are destitute beyond belief, that they are dependent on a single crop, that exporting potatoes and beef from Ireland (where all the money goes to the landlords, and the cotters get the privilege of living another year for their efforts) while putting crazy tariffs on the import of foodstuffs is going to lead to disaster - and they've been screaming it for years! When famine and blight hits, the response of the British government is largely "bootstraps, bitch!". It didn't take me too long to dig out, but here's an excerpt from Ralph Bernal's speech to the Commons in December 1846 on the efforts of the Commons: quote:This [Famine and Typhus epidemic] being the awful state of affairs, was the House of Commons to stand still waiting for the dilatory proceedings of railway companies, commissioners, and boards of works? It was all very fine to talk of teaching the Irish people to depend on themselves, and to buy oats and barley for their own use. Where were they to get money to purchase food? A vast proportion of the Irish population had no money in their pockets to buy either such provision as was indigenous to the soil, or such as might be imported. What arrant nonsense it was, then, to bid them buy food! Were they to be starved to death pending the arrival of the period when riches would come upon them? When a system is engineered to produce an extremely fragile wealth-creating machine that is one variable away from total and catastrophic failure, and repeated attempts to reform the system to be more robust and less cruel are blocked by the vested interests, the famine that inevitably results - and has been predicted by a Royal Commission no less - is engineered. So, in essence: quote:some moustache-twirling guy in the British government sat down and explicitly thought to himself 'how can I make as much money off Irish people as possible, with possible catastrophic famine as an acceptable cost of doing business' Edit: as I wrote that out, I realised that I remember a crazy amount of detail based on some books I read a few years ago, and also that the parallels to the current economic crisis are horrifically obvious

|

|

|

|

It's not genocide, except I suppose in the slightly absent minded sense of "it would be better if the Irish Catholics weren't there". It is not an actively genocidal frame of mind, but one where a famine fits into both a moral narrative ("these people are incapable of bootstrapping themselves out of the situation, so let them die") and a political one ("Ulster is Protestant, and organised differently but let's ignore that, and therefore more Protestants = good"). The question was that whether it was engineered, not whether it was genocidal. It can't be considered a deliberate attempt to kill all Irish Catholics. It can be seen as a situation that was set up and allowed to run, despite the clear warning signs, widely discussed knowledge and explicitly stated findings of a Royal Commission on poverty and potential implications of monoculture, that everything would turn to poo poo with a cost of millions of lives. The government was not genocidal, but it certainly engineered the situation to the point where famine was the only foreseeable outcome and they knew that. I would delve back into Hansard, but Jesus Christ the third person narrative used in mid 19th century parliamentary debates raises my blood pressure to dangerous levels. Edit: I'm fairly sure they used third person in the transcription, which makes sense, but it's still bloody annoying Edit again: It is worth saying that with the Indian famines, it was apathy and profit unbridled. I don't think in those cases (though I could check) that the loss of millions of lives in, say, the Hindu population was seen as an unintended but acceptable side effect so that more land could be opened up to good, say, Muslim tenants. lenoon fucked around with this message at 00:02 on Jan 29, 2016 |

|

|

|

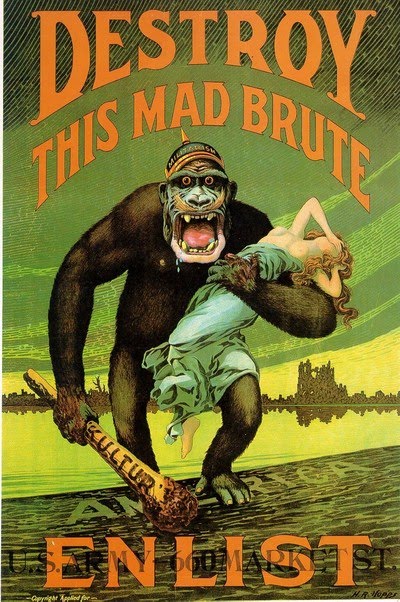

Fangz posted:It's kinda the subtext behind the British propaganda during the Battle of Britain, but more generally was probably in place around WWI. This is American WW1 propaganda - you can see that the woman is the statue of liberty, and I've always wondered at the racist imagery of slavering-ape-beast-after-white-women, and the utter bastard skill of propaganda artists who were able to channel anti-German feeling (a pretty low ebb) into race hysteria.

|

|

|

|

ALL-PRO SEXMAN posted:Seems like it's the other way around. They channeled their honkey racism against the Germans for a little while. Ah, yeah, that's what I meant. Clumsy wording.

|

|

|

|

From my limited reading into the post-first crusade settlement of Palestine by the Franks, there seems to have been little in the way of a racial barrier between incoming settlers and residents of the area. There's more than a few accounts of what we'd now consider, I guess, mixed race marriages, along with conversions to and from the myriad local religious variations, bastard and non bastard children being sent home, mercenaries, traders etc etc. I suppose the dominant classification form was on religious grounds, skin colour probably significantly less important than are you a muslim: yes/no. I'd presume the same kind of thing operated until much later, when a more explicitly colour based categorisation developed in the 18/19th centuries.

|

|

|

|

Ends up being a complicated question - the Geneva conventions themselves are enormous. If we take just the Fourth - protection of non-combatants and prisoners during wartime, I'd be hard pressed to find a single war where it was adhered to by a single side let alone both. Britain is a pretty good example, key signatory to the fourth convention and signatory to all conventions, amendments and additions (unlike the US). Since 1948 we've embarked on.... 6? wars that could be described as part of the decolonisation process as we dug our fingers into the decaying remnants of empire, and each one was marked by deliberate and accidental targeting of civilian populations. Kenya, probably our greatest post ww2 moment of infamy, was a guerrilla war that we fought almost entirely by torture and arbitrary detention and almost entirely against civilians. Post decolonisation, we've had the Falklands, A few UN operations, Iraq 1 and 2 and, Libya: the revengening, Afghanistan part 3: this time we're going to do even less than we did last time, and I lenoon fucked around with this message at 07:47 on Jun 5, 2016 |

|

|

|

Trin Tragula posted:

I have literally no idea what the gently caress I was on about with that. Not going to defend it in the slightest. I'd blame sleepiness or the pernicious influence of work, but tbh I think I was just reflexively recoiling at the idea of Thatcher fighting Britain's only war that didn't involve a serious breach of the Geneva Conventions.

|

|

|

|

Seems Dutch to me - Smaak de Smaa?

|

|

|

|

Hey Trin, if you're looking for more diaries, have you encountered the ludicrously bloodthirsty Ernst Junger? I presume so, but I haven't had a chance to go back through your posts yet. There's a nice penguin translation out.

|

|

|

|

I'm sure I've encountered jungers diaries in translation on some military history forum - maybe GWF - out in the wild as it were. I'll scout around and see if I can find the link again. Edit: It's the contrast between the (extensive) reading of the myriad junior officer diaries I've read on the British side, and the phrasing of the same spirit of triumphalism from Junger, which tends more towards the feeling of invincibility and enjoyment of combat in a more.... Confrontational way than the vast majority of other memoirs I've read. He enjoys it, becomes alive in it, triumphs in it. Oddly enough, the closest other writers and diarists I've read have been D'Annunzio and Lawrence. Now, that's either a translation issue, as I've only read storm of steel in English, or its Junger expressing the will to power in a manner that lusts after battle. Of course, there's the legendary (from a translation given in Der Spiegel): "I found two fingers still attached to the metacarpal bone near the latrine of the Altenburg fortress, I picked them up and had the tasteful idea of having them worked into a cigarette holder" Of course from the same article we have his own words on his bloodthirstyness: "In a mixture of feelings brought on by excitement, bloodthirstyness, anger and alcohol consumption, we advanced towards enemy lines" I am not saying Junger was any more or less bloodthirsty than most combatants (equally "ludicrously bloodthirsty", Lawrence's seeming obsession with the dichotomy of clean and dirty death, for example) mainly that he wrote in a less restrained way about his experiences than others. That "it was a jolly good scrap" on the other side of the trenches was another way of expressing bloodlust, passed through a different cultural filter. Edit 2: Hogge Wild posted:It's been some years since I read Jünger's Storm of Steel, so I might misremember, but I don't recall him coming across as "ludicrously bloodthirsty". I even googled it and found only a Daily Mail article that described him as such. What I remember is that he seemed to be one of those people whose brains seemed to function differently than other people's and he didn't seem to affected by the horrors of war like others were. This is a good point - I treat the detachment which he exhibits pretty much from the word go a symptom of what I'd describe as bloodthirst. It's not the enjoying the act of killing, so much as the enjoyment of the process that war created, industrialising this very Nietzschean philosophy of individualism and nihilism into a wholesale Europe-wide experience which Junger revelled in. Another excellent quote: "It is he, the most dangerous, bloodthirsty and purposeful being that the Earth has to carry" lenoon fucked around with this message at 17:01 on Feb 8, 2016 |

|

|

|

Julian Grenfell is the same, enjoying the whole experience and unabashedly writing endlessly about how it spoke to his "barbaric disposition". Goes well with Junger's embrace of the savagery encouraged by the war. There's a pretty good book by Alfredo Bonadeo called "mark of the beast" that goes into detail about the difference between the gradual emergence of bloodlust and nihilism that is a common theme of diaries and war literature and those that went into war already pretty much cognisant of, and celebratory in, the brutality of it. So Junger has his Nietzsche, Grenfell has his vengeance, Lawrence submits himself willingly to the surrender of the "over mastering greed of victory", where the "selves converse in the void, and madness is very near". It's a good, though unrelentingly harsh book which draws hugely on the Italian front and experiences there, and is generally a great read.

|

|

|

|

bewbies posted:I suppose I'm annoyed your hyperbole, in that case. "Enjoying" the war, such as it was, or enjoying the sensations of combat does not equate to "ludicrous bloodlust". So there's an aggressive tone here that I don't really think is justified, especially seeing as I then explained the position further. Junger doesn't write about drinking from the skulls of his enemies, but Storm of Steel is an (editorialised) account of him willingly subsuming his ego into the Nietzschean ideal of the perfect nihilist. He doesn't take joy and pride in torturing his enemies, but he does celebrate the philosophical and psychological freedom that war affords him through the enjoyment of killing. Now, ludicrous is a subjective term, yes, but to someone who has read a lot of diaries of war, and accepts that men and women have, do and will enjoy both the physical and psychological experience of armed conflict, Junger stands out as ludicrously bloodthirsty because he not only enjoys the experience, but believes that he is right to do so. His experience of war is transformative, the bloodthirst allows him to be the person he wants to be. Probably should have started off by saying "these memoirs that are evidenced by their belief that the war was a spiritually and philosophically positive process that transformed man into something bigger and better than himself, to be "ludicrously" bloodthirsty". But, sadly, I didn't. If anything, guilty of posting all too rapidly - mistaking the penguin reissue of storm of steel for a reissued set of diaries, sorry. Jungers writing is about as "honest" as anyone who by all accounts systematically went through his own experiences to rework them into the ideal of the nihilist ubermensch. If I'm accused of politicising an honest memoir, probably best not to start off with that one. A clumsy modern political statement vs a clumsy post-war political statement, I suppose.

|

|

|

|

Even working in Conscientious Objector memoirs and recorded interviews, you can see the same effects, despite the fact that ostensibly at least, no one did anything violent or (except in some cases) anything they would regret. The immediate post-war memoirs tend towards honesty and anger at the system with a side order of hagiography directed at the "heroes" of the movement, Fenner Brockway, Clifford Allen and the first of the COs to die, Walter Roberts. "Soul of a Skunk" and "the dream of a Welshman in borrowed clothes" are both good examples of this period and style. That kicks into overdrive in the 30s, when memoirs focus more on the dead, the futility of punishment for conscience and the futility of war - understandable with war looming - but the anger at the establishment for the treatment of First World War COs starts to wane in 38-39, I think largely because by that point so many COs were in Parliament, busy setting up conditions for the trial and imprisonment of COs for the next war. Fenner Brockway ends up like this and wrote extensively (on everything) By the time the Imperial War Museum and pacifist movements start to go round the country interviewing people just before they die, the incandescent anger has calmed into reminiscence, and it's only in extreme cases that they still speak about the military system with anger, mostly it's become the resigned calm of the long-term pacifist in the 20th century. Old men chuckling about how they outwitted prison guards and believed that the only good violence was revolutionary violence is always charming, though.

|

|

|

|

Ive often wondered with Ungen-Sternberg whether or not he's just a figure inserted in by the hand of history thinking "this 20th century is not insane enough yet". It's almost too insane to be real. I guess the English Civil War produced a fair few generals, majors and colonels who were considered crazy at the time - and have since largely been rehabilitated away from "totally batshit insane by the standards of the day" to "indistinguishable from tumblr". Major William Rainsborowe, a Ranter, possible nudist, publisher, arms dealer, leading participant in the Putney debates, carried a personal standard depicting Charles 1st's head mid-severance. Got heavily into the mystical implications of the civil war, eventually arrested for treason and arms dealing, emigrated to Boston where he apparently carried on being a Ranter and a nudist. Good poo poo.

|

|

|

|

Disagree on the strength of the often cutesy British WW2 insignia, especially the famous 7th armoured. Lightning bolts? Skulls and crossbones? No. We are British men and we use the fearsome Jerboa. I suppose though I'm inclined to pick it as the coolest insignia because when I was little, there always seemed to be these old men on the train who would tell me these stories of the desert, show me these ancient jerboa tattoos and generally keep me spellbound and quiet for a while. It was one of the things that ended up with me getting into archaeology as a way to go out to Libya and live in the desert for a few weeks. I wonder why there were so many old desert rats living in Leeds and Bradford in the late eighties?

|

|

|

|

Nebakenezzer posted:Is this some sort of Puritan formation I think only the most ardent Irish nationalist would believe Cromwell fought with an axe called "gorechild". "You have sat too long for any good you have done lately, ln the name of the god emperor, go!"

|

|

|

|

I remember when the Nairobi westlands attack happened there were a couple of posters writing good contextual background on the kenya/somalia situation - I'll try to dig up the thread if you like as it might save you some time with the deep dark background. Looking forward to more!

|

|

|

|

I haven't written much about conscientious objection for a while, so have the decidedly non-military history background to my absolute favourite conscientious objector: A Goon Objects - George Baker The story of the Absolutist COs who refused any compromise with military authority is very interesting and a great look at the intersection of civil and military authority during the First World War, but to be honest I write about it enough in generalities that it's worth just looking at one objector as a case study: George Baker. George was born in 1895, making him 21 when the Military Service Act came into power, and, as a single man working as a bank clerk this put him right into the first group of men called up as conscripts. Without dependents, a nationally important job, or powerful connections, he was, in many ways, the ideal conscript - young, unattached and fit, a potentially perfect fighting soldier. But instead, he went through the NCC, to prison, nearly went mad, helped to write an underground prison newspaper and then went back to his life as if nothing had happened. A very ordinary, very brave and above all, very goony man. Why George? He was born into a poor family in what was then the tiny hamlet of West Blatchington, near Brighton. Possibly the most English of all the English places, family backgrounds and people, he maintained throughout the war the kind of quiet, ashamed patriotism that is so very typically English: “I am, also, a patriot. I love my country, and it’s heroic poor who are the salt of it’s English earth. I delight in the rich English tongue, in the loveliness of it’s poetry and in the comeliness of it’s prose.” He’s a good man - a nice man, truly - who worries about the people around him, understands the brutal effects of poverty, sees his place in the world honestly, writes (self-confessed) terrible poetry and thinks about the “ghosts” of the lost potential of his ancestors, the sacrifices his father made to get his son an education, his grandmother as a young girl astonished by gaslights. In another decade, and with a little more family money, he would have been a foreign office civil servant, writing an ethnography when then empire forgot they’d posted him to some distant land. In another century, I think we would have been friends. It’s what he disliked that made him a Conscientious Objector. He hates the grinding poverty he sees around him, the wage disparity between rich and poor, the “white bearded old men” around the world that want to shepherd “poor Tommy and Hans and Jean into their crazy double-ditch of death”. In 1906 he “meets” a socialist friend, becomes an unconvinced and unconvincing athiest - “religion was a thing that could make men fear God, and hate one another”, and grows up. Writing from the vantage point of 1921, it’s this moment that he feels “Wormwood Scrubs had thrown its first faint shadow in the direction of the growing boy.” But George is my favourite because he’s not a grandiose man. He’s “a mushroom. A little man, a man with roots. I belonged to the people, and the people to which I belonged was the people of the very poor.” No bombast, no revolution. Our database of COs describes him well: “Socialist - unattached. Non-sectarian.” To 1916 George’s autobiography, “Soul of a Skunk” was written for his son, “that he may know what Daddy did in the Great War”. It’s surprisingly, incredibly, unashamedly honest. George as a child describes himself as a “detestable three year old”, and recounts his fears (of the sea, of his father’s office boys, coffins, death, graves) honestly, and rather unfortunately, seeing as he grows up by the sea and his father was an undertaker. He’s fond of puns - after being terrorised by Phillip, his father’s assistant, he remarks: “I told neither my father nor my mother of these ... philippics” and grows up a dreamy, introspective child, as immersed in the military culture of Edwardian England as anyone, wearing imitation uniforms and reading about famous battles (“O tempora! O mores!”). He “heartily enjoys” reading about the how the “wicked Boers were making war upon Good Queen Victoria”. At school he picks up a “prejudice against sheep”. A typical story of a working class victorian childhood - "Society, which fears the socialist, Authority, which abominates the pacifist, make of a normal child both one and the other” He dallies with atheism at school and settles down as a confirmed agnostic, hostile to the Authoritarian God of the Church of England - the “Humpty-Dumpty God” in his autobiography, but accepting of the distant, theist God, who he will never meet. He picks up a more firm socialism from reading about Kier Hardie, the class system and England’s feudal history. He has a run in with a local aristocrat over a basket of blackberries, which is “one more milestone on the road to Wormwood Scrubs”. He thinks that if politics has failed the people, it’s time to change the politics. In 1906, he reads about Philip Snowden, Liberal turned Labour MP, Socialist, Feminist and Radical. George is overwhelmed by the argument, and will, after the war, name his son after his hero. He’s sent to Grammar school on a scholarship and made constantly aware of the fact. A second class citizen on account of his family and birth, he hates the “snobs” around him, and loves latin and Shakespeare, and imagines King Lear to be about the Conservatives and Liberals versus the Labour Party. He writes “scribbles” of poetry: “He said that I might sent him jottings for the “Gossip” column of his Gazette. I was most thrilled... He printed one of the three. It contained exactly thirty words and entitled me, i suppose to a postal order of two shillings and sixpence. I was eaten up with pride. Alas! pride went before a fall; I never received the postal order” At 17 he’s working for a bank, and is, wonderfully, an edwardian version of a goon: “Midway to Wrotham on a late February night, a girl whom I overtook disconcertingly said “Good evening”. I was startled, but succeeded in stammering a “Good evening” in reply to her own. “Will you come for a walk?” she asked” What does our boy George do? “I mumbled something about a train and my need to catch it, and began to run” If only he’d been carrying a printer. By 20, he actually knows what sex is - thanks to a kind colleague who “scribbled symbols; crude sex symbols still to be seen, I believe, scratched upon the walls of the excavated Herculaneum”. He falls in love with a girl called May, and writes her reams of terrible poetry, and kisses her on her birthday. A “beautiful brown slip of a girl”, he will think of her often, despite her terrible singing and her repetition of “How Jolly!” whenever George comes out with some grand and romantic comparison to one of the great beauties of classical fiction. When the war begins, George is firmly in love, firmly a socialist and in every other sense firmly nothing at all. Like millions of others, he’s not stirred to volunteer, not because he hates war (though he does), but because he has his new bicycle, his girl, and he’s just met another, very briefly, that he will remember forever - a fiery, beautiful militant suffragette who inspires him and hardens his resolve, in a classic edwardian encounter - being insulted by the police and stoned by a mob of idiots. All this goony idyll is to be shattered, and George's politics and idealism put to the test, but for now: “In August the Old Men of Europe made their mobilizations; tore up their scraps of treaty-paper; invaded glorious little Belgium and diabolic East Prussia and began a four year massacre of Europe’s youth. I cared for none of these things. I cared for my little brown slip of a girl, the verses I made for her, the books I read for her.” lenoon fucked around with this message at 12:43 on Feb 23, 2016 |

|

|

|

I think he's an example of how all that imperialism and golden age of Englishness, all the romance and poetry and daft innocence didn't have to lead to being a soldier - there's this kind of irresistible historical inevitability of the "long hot summer of 1914", where sleepy England stirred itself to war, but the same conditions and the same "ideal" of the nation of shopkeepers also produced an anti-war movement, from the very same people. I love the guy. More soon!

|

|

|

|

More Baker before bed, I think: George Baker goes to War When we left absent-minded romantic socialist George Baker, he was sunning himself in the regard of his girlfriend, comparing her to cherry blossom, working as a bank clerk and reading endless socialist literature. Truly, the last great summer of the old world. But now it’s September 1914 and George’s pacifist tendencies are now well known in Steadingbourne where he works. Accosted by “chattering feather-head women” he’s transferred away by the bank, leaving behind his girlfriend and her habit of saying everything is “Jolly!”, which George, like the goon he most certainly was, has already started to resent. He’s moved around a lot in the early years of the war, filling in for positions vacated by volunteer soldiers. He’s in Chatham when submarine action fills the town with mourners, and his pacifism takes a knock: "I wavered, overcome with horror of this sorrowful thing, tortured by doubt as to whether the Germans who compassed it might not be the power-thirsty, blood-thirsty devils painted by the Bandar-Log (Monkey-People from Jungle book - here referring to the patriotic mob) press” He’s back with his “little brown slip of a girl” at the beginning of 1916, but avoids her - having been told that bands of soldiers were looking to attack him if seen with her (something he later identifies as “libel against the Tommies; no man in khaki at any time offered me violence”). In fact, his first white feather comes from a woman on the arm of a soldier: "This girl called upon her soldier escort to give the “Pro-German Skunk” what for. Her soldier escort disappointed the lady by saying disconcertingly “Put it there, Sonny, and stick it out”” a not unusual response from soldiers home from leave. When conscripted in March, he assesses his position. He’s not against Conscription - he sees it as a useful component of socialism, provided that it puts the rich to work in the mines, and doesn’t like religious or political bodies. He wants to be judged on his own merits, and the merits of his argument, which he puts to the local Tribunal: “The Old Men of Europe had divided the world into two camps. They had made the young men dig two long and narrow ditches across Europe’s face. They had compelled Europe’s young men to become ditch-men and cave-men, and to translate Stone-Age barbarities into terms of poison-gas, liquid-fire, land-mine and aerial torpedo. For myself, I would be neither ditch not cave man. I was, or I sought to be, civilised. I stood for civilisation against barbarism, for internationalism against nationalism, for peace against patriotism, for love against hate.” It goes down like a lead balloon. With the unmistakable arrogance of your early 20s, George has claimed that “I have not a conscientious objection, so much as an intellectual and emotional objection”. He does not object to war out of “conscience”, which he does not believe in, but out of intellect. He has reasoned his way to his stance, and expects the Tribunal to respect that. Of course, the Tribunal has no recourse to grant him an exemption based on intellect - conscience is very much the magic word. This is a man who has, in his rational mind, actually denied that he has a conscientious objection. The first time I read it, I actually said "oh god George". But the tribunal is not as harsh as it could be - they grant him “Exemption from Combatant Service Only”, the standard verdict, and he will be expected to go to the Army as a non-combatant. George finds this unacceptable, and appeals to the County Tribunal in Canterbury. His appeal process will take a while, though, and in the meantime he finds the town of Sittingbourne hostile: "I found written, with obscene variants, such inscriptions as “Baker is a Conchy Coward” and “Baker is a Pacifist Skunk”... Their elders conspired to give me what they termed “rough-houses”. On each occasion, to demonstrate their courage over my own, they “rough-housed” me two or three, or even half a dozen strong” He hides it from his girlfriend and landlord, but he’s getting pretty badly beaten. Bruised but not broken, he doesn’t even attempt to argue his case at the Appeal Tribunal, but instead states that he’d go to prison before he went to the army. He does so because it's what his hero, Philip Snowden, would have done. And also, as he admits, he's caught up in the defiance of it, the thrill of going against the status quo, making a stand and saying to the world at large "I am a socialist, and I say NO". He's never done that before - always quietly working, listening to the bandar-log chattering their patriotism at the bank, hearing his father's conservative Conservatism, and seeing the press and public whipped up into bloodlust. But no longer! No more appeals to reason, he's given the chance, at 21, to stand up to authority and nail his colours to the mast, one great and grand gently caress you to authority (He doesn't swear in his autobiography, but he talks about swearing a lot). It's all for nothing. Appeal rejected, and he's told, in no short terms to sit down, shut up and be glad of his non-combatant status. He's resolved to reject non-combatant service, so George goes home and tries to work out what to do next. Unfortunately, he decides on suicide. Though he himself mocked his attempt as "an adolescent emotional" decision, the reality of it was very serious. Aside from his goon tendencies and possibly having somehow preinternalised e/n's kill u are self advice, the fact that he wrote about his suicide attempt in an autobiography dedicated to his son says a lot about George. He wanted him to know about it - about the enormity of what his father had set to do, and why. I'm going to leave it for another post - probably need a more serious tone.

|

|

|

|